| This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article's talk page. (November 2024) |

| Anne de Montmorency | |

|---|---|

| 1st Duc de Montmorency Constable of France Grand Maître of France | |

Portrait by Corneille de Lyon Portrait by Corneille de Lyon | |

| Born | c. 1493 Chantilly |

| Died | 12 November 1567 Paris |

| Noble family | Montmorency |

| Spouse(s) | Madeleine de Savoie |

| Issue Detail | |

| Father | Guillaume de Montmorency |

| Mother | Anne de Saint-Pol |

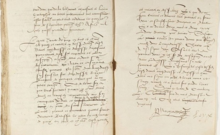

| Signature |  |

Anne de Montmorency, duc de Montmorency (c. 1493 – 12 November 1567) was a French noble, governor, royal favourite and Constable of France during the mid to late Italian Wars and early French Wars of Religion. He served under five French kings (Louis XII, François I, Henri II, François II and Charles IX). He began his career in the latter Italian Wars of Louis XII, seeing service at Ravenna. When François, his childhood friend, ascended to the throne in 1515 he advanced as governor of the Bastille and Novara, then in 1522 was made a Marshal of France. He fought at the French defeat at La Bicocca in that year, and after assisting in rebuffing the invasion of Constable Bourbon he was captured at the disastrous Battle of Pavia. Quickly freed he worked to free first the king and then the king's sons. In 1526 he was made Grand Maître (Grand Master), granting him authority over the king's household, he was also made governor of Languedoc. He aided in the marriage negotiations for the king's son the duc d'Orléans to Catherine de’ Medici in 1533. In the mid 1530s he found himself opposed to the war party at court led by Admiral Chabot and therefore retired. He returned to the fore after the Holy Roman Emperor invaded Provence, leading the royal effort that foiled his invasion, and leading the counter-attack. In 1538 he was rewarded by being made Constable of France, this made him the supreme authority over the French military. For the next two years he led the efforts to secure Milano for France through negotiation with the Emperor, however this proved a failure and Montmorency was disgraced, retiring from court in 1541.

He spent the next several years at his estates, relieved of the exercise and incomes of his charges, and removed as governor of Languedoc. He allied with the dauphin, the future Henri II during this time in his rivalry with the king's third son. Upon the dauphin's ascent in 1547 Montmorency was recalled from his exile and restored to all his offices, with his enemies disgraced. He now found himself opposed at court by the king's mistress Diane de Poitiers and her allies the duc de Guise and Cardinal de Lorraine. He led the crushing of the gabelle revolt of 1548 and then the effort to reconquer Boulogne from the English which was accomplished by negotiated settlement. In 1551 he was elevated from a baron to the first duc de Montmorency. In 1552 he led the royal campaign to seize the Three Bishoprics from the Holy Roman Empire, though was overshadowed by the glory Guise attained in the defence of Metz. Montmorency led the inconclusive northern campaigns of 1553 and 1554 and was increasingly criticised for his cautious style of campaign. From 1555 he led the drive to peace that secured the Truce of Vaucelles in mid 1556, however the peace would be shortlived. In 1557 he was again tasked with fighting on the northern frontier, and was drawn into the disastrous battle of Saint-Quentin at which he was captured and the French army destroyed. Guise was thus made lieutenant-general of the kingdom, while Montmorency tried to negotiate peace from his captivity. The king supported him in this from late 1558 and in April 1559 he would help bring about the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis which brought the Italian Wars to an end.

When Henri II died in July 1559, Montmorency was sidelined by the new Guise-led government of François II, which relieved him of the office of Grand Maître. He would not participate in the Conspiracy of Amboise that attempted to overthrow the Guise regime however. When François in turn died in December 1560, he was recalled to a central position in the government, though subordinate to the role granted to the king of Navarre who was made lieutenant-general by the new king's mother, the regent Catherine. He quickly became disenchanted with the new government and entered opposition alongside Guise and Marshal Saint-André, forming an agreement known to history as the 'Triumvirate' in 'defence of Catholicism'. When the French Wars of Religion erupted the following year, he and his Triumvirate colleagues secured the royal family for their cause and fought against the Protestants led by Navarre's brother, the prince de Condé. In the climactic battle of the war at Dreux Montmorency was again made prisoner, and from his captivity negotiated the peace with the likewise captive Condé. During the peace, he joined Catherine and the court for the grand tour of the kingdom and feuded with his former ally Guise. In 1567 the Protestant aristocracy led a new coup against the crown and Montmorency led the defence of Paris against their army. Pushed to confront the Protestants, Montmorency died as a result of wounds sustained at the battle of Saint Denis on 12 November 1567.

Early life and family

Anne de Montmorency was born in 1493 at Chantilly, the son of Guillaume de Montmorency and Anne de Saint-Pol. His parents named him for his godmother, Anne, queen of France. Guillaume held a senior position in the household of the future king François I (at that time, comte d'Angoulême).

The Montmorency family prided itself on being the 'oldest barons' in France. Indeed, Montmorency's son would later boast to the English ambassador that the barons of Montmorency existed before there were kings of France. Despite these boasts, Montmorency was not a prince, and therefore his rivals the Lorraine family had a greater pedigree than he did. Montmorency would however fire back that he was a true born Frenchman, while the Lorraine family were 'foreign princes'. This criticism stung his rivals, who were pleased to see the barony of Joinville raised to a principality in their favour in April 1552 so that they would no longer be 'foreign princes' but 'French princes'.

Marriage and children

Montmorency married Madeleine de Savoie, a cousin of the king François I on 10 January 1527. Their marriage was sumptuously celebrated by the king during a period of extravagance at court which contrasted with the relative paucity of funds at the disposal of the household of the king's captive children in España. This marriage brought Montmorency into the royal family and going forward the king's mother and sister referred to him as their nephew. Madeleine brought with her to the marriage family lands in Picardie. Her brother, Montmorency's new brother-in-law was Claude de Savoie, comte de Tende the governor of Provence. He was thus afforded a relation with powerful interests near his governate of Languedoc that he lacked in terms of personal feudal control. Together they had the following issue:

- Éléonore de Montmorency (1528–1556), married François III de La Tour d'Auvergne, vicomte de Turenne in 1546 and had issue.

- Jeanne de Montmorency (1529–1596), married Louis III de La Trémoille, duc de Thouars in 1549 and had issue.

- François de Montmorency (1530–1579), Marshal (1559), duc de Montmorency (1567), governor of the Île de France (1556). Married Diane de France in 1557 without issue.

- Catherine de Montmorency (1532–1595), married Gilbert III de Lévis, duc de Ventadour in 1552.

- Henri I de Montmorency (1534–1614), duc de Montmorency (1579), governor of Languedoc (1563), Constable of France (1593). Married Antoinette de La Marck in 1559 and had issue.

- Charles de Montmorency (1537–1612), sieur de Méru then duc de Damville. Married Renée de Cossé in 1571 without issue.

- Gabriel de Montmorency (1541–1562), sieur de Montbéron.

- Guillaume de Montmorency, (1544–1591) sieur de Thoré. Married Léonore d'Humières in 1561 without issue.

- Marie de Montmorency (1547–1572), married Henri de Foix-Candale in 1567 without issue.

- Louise de Montmorency, abbesse de Maubuisson.

Several of Montmorency's sons were afforded the privilege, by his senior station at court, to become enfants d'honneur (children of honour), which meant they were raised alongside the royal children. For his daughters, Montmorency secured prestigious marriages into esteemed families, including La Trémouille, Ventadour, Foix-Candale, and Turenne. These were all great lords in the south west of France, important in Poitou, Limousin and Auvergne respectively. He provided his daughters with suitably grand dowries, the eldest three bringing 50,000 livres to their marriages, while the last brought 75,000 livres. His sons meanwhile were all introduced to military careers by their father, with none destined for the church.

His eldest son, François transgressed against his father's plans for his marriage into the royal family by exchanging legally binding paroles de promesse with Jacqueline de Piennes. In reaction to this 'betrayal', Montmorency got a law passed in 1557 that allowed a father to disinherit a son under the age of 30, or a daughter under the age of 25 who married without their parents permission. The law was retroactive, thereby obliging his son to annul the arrangement. He further had Jacqueline confined to a convent. His intended marriage of his son to Diane would go ahead on 4 May 1557, thereby further uniting the Montmorency with the royal family.

The death of his daughter Éléonore and her husband left Montmorency with the responsibility to raise the future Marshal of France, the vicomte de Turenne.

Relatives

Unlike the Lorraine family he would not take advantage of his power to put many of his relatives into senior positions in the French church, this left the field open for his rivals to dominate the senior positions of the French clergy.

Montmorency's sister Louise de Montmorency was an early secret convert to Protestantism among the great nobility and married Gaspard I de Coligny. Her husband died in 1522, and therefore Montmorency and his sister would jointly raise his nephews, who would all be drawn towards Protestantism. Montmorency was greatly attached to his lineage, and thus despite his strong religious convictions did not formally oppose them for some time.

Through his sister, Montmorency had three nephews who would go on to play an important role in the early French Wars of Religion. Gaspard de Coligny, Odet de Coligny and François de Coligny all converted to Protestantism and led the movement with zeal. The first, would become Admiral of France, the second most senior role in the French military, while Odet would become a Cardinal at the age of 16 due to Montmorency's influence. Montmorency's sons would not follow his nephews into Protestantism.

Religion

In religious temperament Montmorency, and his wife, were firmly Catholic, and were displeased by the Protestantism Montmorency's sister and nephews adopted. Montmorency's four sons would share his Catholicism, though both Thoré and Méru were sympathetic to Protestantism at one point or another. During his political ascendency, he received concerned reports of the growth of Protestantism in south-west France. Montmorency's Catholicism was not Ultramontane but rather highly Gallican in disposition. It was therefore with Montmorency's encouragement that Henri II flirted with the possibility of schism with the Papacy. He objected to the political program that often existed alongside Protestant movements in France, which advocated radical reforms. Despite this, the realities of Protestant opposition to the power of the Lorraine family in the 1560s meant that Montmorency was drawn in a more tolerant direction by his sons. He would have great affection for his nephews despite his disapproval of their religious persuasion. For Montmorency it was understood that the war on heresy that he supported was not meant to target members of the social elite (such as his nephews). So long as they publicly conformed it was no ones business what they did in their private chapels.

In his later years, Montmorency was afflicted with Gout.

He had a reputation as a taciturn man, something which contrasted with some of his more refined contemporaries in the French court. He was described by contemporaries as a 'bluff soldier' and conservative in temperament.

Wealth and estates

With many offices to his name, by 1560 Montmorency enjoyed an annual income from his various positions of 32,000 livres (pounds). This direct income from the crown did not include the revenues he received from his many estates and territories across the kingdom. With his various estates factored in, Montmorency enjoyed an income of around 180,000 livres in 1548, which dwarfed the income of the Bourbon-Vendôme princes of the blood that sat at around 71,000 livres. At the end of his life in 1567, Montmorency enjoyed pensions totalling 45,000 livres, alongside his income from the office of Constable which was around 24,000 livres, and an income from his land of 138,000 livres.

Indeed, by land the Montmorency were the wealthiest non-royal family in France. It was said that they had more than 600 fiefs to their name. Alongside his great wealth, the Montmorency family could count on more clients than any other 'private' family in the kingdom. Montmorency had great landed interests in the Pays de l'Oise, Vexin, Picardie, Bourgogne, Normandie, Champagne, Angoumois, Berry and Bretagne.

Châteaux and residences

The Montmorency family had great landed estates in the Île de France, including the famous Châteaux of Écouen and Chantilly.

The Château of Écouen was built under his direction beginning in 1538, meanwhile Chantilly was restored at his request from 1527-1532. Écouen was a testament to the new architectural style of the period, and was renowned for its beauty, it featured sculpture work by Jean Goujon (such as the sculpture of victory wielding the sword of the Constable, which hung over the fireplace) with the architecture overall led by Jean Bullant. Écouen featured two statues by Michelangelo that had been gifted to Montmorency by François I (originally destined for the tomb of Pope Julius II), along with mosaics of coloured stones and an elaborate courtyard. The emblems of Henri II, Catherine de Medici and his own would be strewn throughout the château. Chantilly was so grand it rivalled a royal palace, the original feudal centre of the château renovated inside in the style of the Renaissance. Beginning in 1524 Montmorency added a long gallery to the château. A small châtelet (gatehouse) was added at the level of the pond.

These were two of the seven principal châteaux belonging to Montmorency, the others being Thoré, Mello, La Rochepot, Offémont and Châteaubriant. The royal family would occasionally stay at his châteaux, as when in 1565 Catherine and Charles IX spent time at Châteaubriant during the royal tour of the kingdom. Henri II also had occasion to stay at one of Montmorency's baronial residences of Fère-en-Tardenois in both 1547 and after the campaign of 1552. In 1531 François was pre-occupied staying at Chantilly with Montmorency when his mother died, and therefore did not come to her bedside.

In Paris itself he had four hôtels (grand residences), one of which featured a room devoted to listening to music to emphasise his 'cultured nature'.

Patron of the arts

Montmorency was also a patron of the arts, and commissioned the famous painter Léonard Limousin who produced an enamel dish which depicted a scene inspired by Raphael in which the various Greek gods were used as representations of the king, queen and his mistress. The artist Rosso Fiorentino produced a rendition of the Pietà for him in 1538. This work is now housed in the Louvre. His châteaux also boasted libraries filled with books acquired from Roma. Montmorency was a collector of antiques, and arms, which he stored in his châteaux.

Childhood

In his youth, Montmorency was a playmate of the comte d'Angoulême future king François I. The two played racket sports together alongside another future royal favourite Philippe de Chabot.

Early career

Ascent of François I

Montmorency saw his first military service in 1511 in the campaigns of king Louis XII and fought at the famous battle of Ravenna in the following year.

When François I ascended to the throne in 1515 he was keen to reassert the French claims to Milano. Montmorency therefore joined the campaign into Italy and distinguished himself in the service of the king at the battle of Marignano in 1515.

Around 1516, Montmorency already enjoyed the privilege of being the captain of 100 lances, even though he was only 23 years old. At this time he was made governor of the Bastille and governor of Novara in Italy.

With relations declining between France and the Holy Roman Empire in 1518, a rapprochement was undertaken with England. Admiral Bonnivet led an embassy to England accompanied by 80 young 'gallants'. The product of this embassy was a series of treaties. Tournai was to be returned to France, in return for 600,000 écus (crowns). Cardinal Wolsey was further financially compensated for the loss of his see (Tournai), and eight French nobles were dispatched to England as hostages pending the final settlement between the two countries. One of the nobles who spent time as a hostage in England was Montmorency.

This was not the end of his advancement early in the reign of François, and around 1520 he was established as premier gentilhomme de la chambre du roi (first gentleman of the king's chamber), giving him privileged private access to the king.

When an Imperial army invaded France in August 1521, Montmorency helped lead the defence of Mézières during a siege.

Marshal

In August 1522 he became one of the Marshals of France, was made a councillor of the king, and was inducted into the Ordre de Saint-Michel (Order of Saint-Michel) as a chevalier (knight).

Montmorency enjoyed poor relations with the comte de Saint-Pol (the count of Saint-Pol) brother of the duc de Vendôme (duke of Vendôme). This complicated matters when Montmorency was established as commander of the garrison of Doullens in 1522 under the authority of Saint-Pol. Saint-Pol refused to depart the province, claiming this would be to his dishonour in their dispute. Saint-Pol enjoyed some support in his push for Montmorency's removal, but the Marshal was not without his own allies.

La Bicocca

In that year, Montmorency fought in Italy under the command of the vicomte de Lautrec (viscount of Lautrec). He received communications from his father at court, who informed him of the efforts the king's councillors were making to ensure the royal finances were in order. Lautrec commanded an army of Swiss, French and allied Venetians. He faced off against the condotierri Prospero Colonna, who commanded the Imperial forces based in Milano in front of Pavia. The arrival of Colonna's army near Pavia forced Lautrec to back off, much to the irritation of his Swiss forces, who were eager to be paid. Colonna (with his army of 18,000) shadowed Lautrec as he pulled back from Pavia, and established himself at Bicocca. Lautrec understood La Bicocca to be a highly defensible position, but the Swiss troops argued in favour of battle which was therefore given.

Lautrec gave the Swiss permission to charge the enemy, while French nobles, under the command of Montmorency followed them on foot in the hopes of gaining glory. Lautrec took the final portion of the army around the right flank hoping to enter the Imperial camp that way. The frontal assault of the Swiss was a bloodbath, the French nobles with Montmorency suffered equally badly and the two groups would constitute a large part of the 3000 dead. After the defeat, the Swiss soon left the army, as did the Venetians, Lautrec himself returned to France where he received a cold reception from the king.

Bourbon's betrayal

To compound the misfortune of the disaster at La Bicocca, France was hit with the treason of Constable Bourbon, who signed a treaty with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V on 18 July 1523. Around this time England, which had previously allied with France against the empire decided to declare war on the kingdom, invading Picardie and the coasts of Bretagne and Normandie. While this situation was developing, Montmorency was charged with raising a new royal army for a southern thrust. He found mercenaries willing to fight for the crown, and with new artillery also assembled, Montmorency brought them to Lyon for a push into Italy. François then travelled south to join the army at Lyon in August, only to be hit by an illness, word of the English attacks in Picardie and the knowledge of Bourbon's betrayal.

François felt it necessary, with Bourbon's betrayal to abandon his plans to join the campaign, and he returned to court to secure the kingdom, leaving the army under the direction of Admiral Bonnivet who led the 30,000 men Montmorency had assembled towards Turin in September 1523, but the army was ravaged by disease and was forced to retreat from Italy in April 1524. On the retreat, Montmorency led the vanguard of the army but became so ill from the plague that racked the army that he had to be carried in a litter. Upon re-entering France, the Swiss troops formerly under Bonnivet's command went their own way vowing never again to work with the French, while the French never again desired to trust the Swiss.

The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was keen to revenge himself on France for their campaigns in Italy, and to this end appointed the 'traitor' Constable Bourbon to lead an army out from Italy into France in Autumn 1524. Bourbon hoped to invade in coordination with an army under the king of England and the Emperor, however neither would join him in the endeavour. Having invaded Provence, Bourbon became bogged down besieging Marseille while François mustered a strong army at Avignon. On 29 September 1524, Bourbon recognised his efforts were hopeless and began a retreat. Montmorency pursued with his cavalry, meanwhile François restored French control over Aix which had fallen to Bourbon. François followed in Montmorency's wake and continued the campaign back into Italy, entering the ducato di Milano (duchy of Milano). Under Montmorency's command were the dauphin and the future royal favourite Saint-André. The dauphin found himself reliant on Montmorency, particularly due to his increasingly difficult relationship with his father François.

Pavia

François decided to put Pavia to siege, and settled in for the winter around the city. The Imperial army, conscious that if they tried to wait the French out their army would dissolve for lack of pay, decided to force a battle with the French. The battle of Pavia was an unmitigated disaster for the French. François, Henri II, king of Navarre, the comte de Saint-Pol, the comte de Tende, future father in law of Montmorency and Montmorency himself were all taken prisoner. The Imperial army was almost overwhelmed by the number of prisoners that they took.

Montmorency and François were held captive in Pizzighettone, alongside other great nobles such as the future Admiral of France, Philippe de Chabot. Montmorency was granted permission to depart his captivity in the service of raising funds for his ransom in early March. Montmorency met up with the royal family and assured them the king was in good health, and urged them to write often, as news of his family was François' greatest joy. After his return to captivity the Papal Nuncio, who had visited the king, would remark that Montmorency was the king's main source of comfort in captivity.

Captive king

Montmorency would not be in captivity long, and was exchanged for Ugo de Moncada. François at first remained captive in Pizzighettone, before proposing to his captors that he be transferred to España. The Imperial viceroy Lannoy agreed, but to stop any mischief by the French fleet requested several French galleys be involved in the transfer. Montmorency therefore arranged with the regency government for 6 galleys to be handed over. The fleet left Genoa on 31 May 1525. Montmorency then travelled to Toledo where he appealed for safe-conduct for François' sister Marguerite to come and negotiate a peace in España and that a truce be declared while negotiations were ongoing. The Emperor allowed all this, and Montmorency went to the regency government to obtain the powers to agree the truce. Philippe de Chabot travelled to Toledo soon thereafter and signed a truce on 11 August.

In exchange for peace, the Emperor demanded that France cede Bourgogne, recognise Imperial control of Artois and Vlaanderen and relinquish their claims on Napoli and Milano. This was too much for François and his mother Louise de Savoie who led the regency. From his captivity in Madrid, François first considered escape, and when frustrated in this, abdication in favour of his eldest son so that the Imperials would no longer possess a valuable captive with which to extort France. In the event of his release, François was to be restored to the crown with his sons regal powers suspended until the formers death. Montmorency and Cardinal de Tournon witnessed the sealing of the decision. Montmorency brought the decision of the king from Madrid to the Paris Parlement (highest court in France) to register, but they refused to consider the king's abdication, moreover the Emperor was not fooled by the manoeuvrer which only alerted him to the value of the king's children. In the treaty which released him from his captivity in January 1526 his release was contingent on the captivity of his two eldest sons as a guarantee that he would cede the land he committed to (including Bourgogne). Montmorency brought the news of the treaty back to France.

In fact the treaty provided two options for the king, either he cede the dauphin and twelve of the kingdom's military leaders (among them Montmorency, the duc de Guise, Lautrec and Admiral Chabot) or he cede both his first and second son. It was this latter course which was pursued, the regent little desiring to deprive the kingdom of its military leadership.

Ascent

Grand Maître

Montmorency was appointed to the position of governor of Languedoc on 23 March 1526. The post had formally been occupied by the traitor Bourbon. In the same year he received this honour he was made Grand Maître (Grand-Master), and therefore given supreme authority over the king's household and the court. In this office he replaced the king's uncle the comte de Tende, who had died of the wounds he sustained at the battle of Pavia. As Grand Maître, Montmorency enjoyed a position as head of the king's councils, which convened under his auspices. He also held authority over appointments in the royal household, court expenditure and security. This authority over the king's household gave him an important intermediary position as regarded the two young princely hostages that had been delivered to the Imperial camp, and it was through him that all correspondence with them would be conducted. For the management of the king's material household, he had at his disposal deputies, including the premier maître d'hôtel (first steward).

Bourbon's sack of Rome in 1527 had the effect of fostering a greater understanding between England and France. King Henry VIII feared that the captive Pope would not be able to sanction his divorce. Therefore Wolsey met with François to talk business in August 1527 at Amiens. It was arranged for Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry to marry the duc d'Orléans and Henry retracted his objection to François' marriage. If war began again with the Emperor, English merchants would maintain their privileges in France. To celebrate the newfound accord, Montmorency was dispatched to England, to award the Ordre de Saint-Michel (Order of Saint-Michel) on Henry, while Henry in turn awarded the Order of the Garter to François.

Captivity of the princes

In December 1527, François convened an Assembly of Notables with the aim of raising 2,000,000 écus to either pay the ransom of his sons, or if the Emperor attached the return of Bourgogne to the ransom, the money would be used to prosecute a new war against the Empire. The Assembly responded positively, with the clergy offering 1.3 million livres in return for the rescue of the Pope, destruction of Protestantism and protection of Gallicanism. The nobility likewise promised their goods and lives. The prévôt des marchands (provost of the merchants) agreed Paris would pay part of the ransom. The promises needed to be converted to money, however the nobility proved less than willing to deliver what they had agreed. Montmorency took responsibility for securing the money required from the Boulonnais but was frustrated that they would only grant him a fifth. He was so upset at their 'insolence' that he did not even pass their offer on to the king. He told the sénéchal (seneschal) that nothing would be accepted from the region until they had committed themselves the way other regions had. Eventually the Boulonnais complied. Due to the 'stinginess' of some parts of France, the king would be obliged to take loans, using Montmorency as the guarantor.

A sensitive matter arose in 1528 as the English king Henry sought a divorce from his wife, the aunt of the Holy Roman Emperor. François was keen to support the English king in acquiring it but was sensitive that open support would be politically dangerous, given his sons were still in Imperial captivity. Therefore he worked on the theologians of Paris through a proxy, and Montmorency took it upon himself to rebuke a syndic named Noël Béda who objected to the divorce, however Béda remained firm. Béda would indeed go on to sabotage the debate at the faculty of theology, much to the disquiet of the English ambassador.

Montmorency had an important role to play in the negotiations that were conducted, beginning 5 July 1529 between Louise de Savoie and Margarete von Österreich. Montmorency assisted the king's mother Louise alongside Chancellor Duprat and the queen of Navarre. Together they would establish a peace agreement known as the treaty of Cambrai or Paix des Dames (Peace of the Ladies). An enormous ransom of 2,000,000 écus would restore the liberty of the princes, while François would have to abandon his suzerainty over Artois, Vlaanderen, Milano and Napoli, but would be allowed to maintain Bourgogne, Auxerre and Mâcon.

During his first period of ascendency in the 1530s, Montmorency ensured the disgrace of the vice-admiral of France (and governor of Le Havre) Charles de Moy. His relations with the vice-admiral would remain poor for decades, as typified by his ensuring that his nephew Coligny would receive the office governor of Le Havre upon the accession of Charles IX in 1560.

As far as the execution of the terms of the treaty were concerned, François delegated responsibility to Montmorency and Cardinal de Tournon. By 29 April 1530, Montmorency was able to show to the Spanish finance-general a large pile of gold already assembled for the Emperor. By May the money assembled would be ready, and handed over to the Spanish delegation. It would however take until June for the entire ransom of 1,200,000 écus to be paid off. By this time Tournon had taken over responsibility for the provision of the money, while Montmorency went to receive the hostages from their exile in España from the condestable (Constable) de Castilla, as well as François' new bride the sister of Charles V. The crossing over of the princes to France and the money to España was scheduled for 1 July to be overseen by Montmorency. The Condestable of Castilla was suspicious of a trap, and halted the advance of the royal children when he received word that a large party of French horsemen were nearby, fearing that the French may take the children and then intercept the ransom. As the hours passed, Montmorency was increasingly concerned that the party of the Condestable had not yet appeared and sent an envoy to find them. Upon reaching the Spanish camp, the representative was told of Castilla's suspicions of a trap, which caused the representative to challenge Castilla to single combat. The new queen of France took it upon herself to threaten Castilla with disgrace if he did not continue with the transfer. Finally it began, Montmorency and the French money departing in a boat from one side of the river to a pontoon in the centre, while Castilla and the royal children did likewise from the other bank. The Condestable provided his apologies to the two young princes for the conditions of their imprisonment, only the dauphin responded graciously.

Guardian of the princes

In the years that followed, it would be Montmorency who devoted himself to the needs and time of the young princes, supervising their days from dawn to dusk in his capacity as Grand Maître, and winning their affection with his attentions and provisions. He oversaw the education of the dauphin and duc d'Orléans (as the king's second son was known at that time), planned out their days and instructed them in the courtly ceremonies in a way the king lacked time for. To support him in providing for the young princes, Montmorency relied on three men, Humières, Saint-André and the comte de Brissac. Several of his nephews (Coligny and Andelot) would be among the enfants d'honneur (children of honour) who had the privilege of being raised alongside the royal children.

Montmorency was close with the new bride of the king and supported her at court. He remarked that 'Frenchman should thank god for giving them so beautiful and virtuous a lady'. This was in contrast to François himself who was more infatuated with his mistress Anne de Pisseleu. Éléonore, sister to the Emperor thus had to content herself with being overshadowed. It would be Montmorency who supervised the arrangements for her coronation, which was undertaken on 5 March at Saint-Denis.

The successful outcome of the payment of the ransom and return of the king's children elevated Montmorecy in the esteem of the court with Montmorency receiving many congratulations. While the court travelled back to the capital, he went to spend some time in his estates at Chantilly.

Picardie

After the treason of Constable Bourbon in 1523 it had become necessary for the duc de Vendôme to devote himself to affairs at court. This meant Vendôme could not fulfil his responsibilities as governor of Picardie. The Parlement of Paris demanded that the province be governed in his absence. To this end in May 1531 Montmorency's brother the seigneur de La Rochepot was appointed to fill the office. The appointment of his brother was a victory for Montmorency in his battle at court with the Admiral Chabot at a time when the hatred between the two men was barely being contained by the king. Montmorency would defend his brother's financial interests in front of the Chancellor of France and supported his methods of raising money for his role as governor at court.

The family's control of Picardie was aided by the presence of two Montmorency clients in subsidiary governorships, that of Péronne and Boulogne. Jean II de Humières the governor of the former accompanied Montmorency in 1527 on his embassy to England, the governor of Boulogne Oudard du Biez meanwhile received a 10,000 livres bounty thanks to the efforts of Montmorency to push the sum through the chambre des comptes (chamber of accounts). Both men reported on their efforts to raise funds for the crown in 1529, the nobility of Péronne refused to shoulder the tenth that Humières proposed, leaving the governor to write to Montmorency for advice on how to proceed. The nobility of Boulogne meanwhile offered a twentieth forcing Montmorency to write to du Biez that such a sum was not acceptable to the king. Du Biez protested that the land was ravaged by the effects of war.

As for Montmorency personally, he had lands around Boulogne, and therefore the presence of his client in the governorship of the centre aided him greatly in the extraction of revenues.

Diplomat

A meeting took place in October 1532 between the English king Henry and François. Great gifts were exchanged between the two monarchs. Alongside the gifts, the duke of Norfolk and Suffolk were made chevaliers of the French Order de Saint-Michel. Meanwhile Montmorency and Chabot became knights of the Order of the Garter. Alongside the gift giving an alliance against the Ottoman Empire was established, however this was a smokescreen for their plans to resist the Emperor in Italy.

The Grand Maître had an important role to play in the marriage alliance concluded between the Papacy and France in 1533. The king's second son, the duc d'Orléans (future Henri II) was to marry the Pope's cousin Catherine de Medici, duchessa di Urbino (duchess of Urbino). Back in September 1530, when negotiations had begun for the marriage, the king had turned to Montmorency for advice on the political clauses of the marriage contract. Montmorency prepared Marseille for the Pope's arrival on 12 October to seal the union. He sailed among the Pope's flotilla as it approach the city in a frigate of his own decorated in Damask, and after greeting him on the shore, escorted the Pope and duchessa di Urbino to the king's garden near the abbey Saint-Victor where four French cardinals (Cardinal Legate Duprat, Cardinal de Bourbon, Cardinal de Lorraine and Cardinal de Gramont) and various other senior churchmen were waiting to receive him.

On 26 October there was a banquet for the assembled dignitaries. The following day, the marriage contract was signed in the Pope's chambers, after which Orléans was led into an audience hall. It was Montmorency's responsibility to bring his new bride, Catherine, into the room where, after Cardinal de Bourbon affirmed the consent of both parties, Orléans kissed Catherine and the celebratory ball began.

Orléans would prove cold towards his wife, with his real romantic interests directed towards Diane de Poitiers, the comtesse de Brézé (countess of Brézé) from 1537. Montmorency had long enjoyed a close relationship with the Brézé, often taking himself up to their Château d'Anet to discuss matters of state with her and her husband Brézé. Montmorency played an important role in facilitating the young prince's romantic indiscretions, allowing for the rendezvous' to transpire at his Château d'Écouen. By 1538, Diane would however have assessed Catherine as her preferred match for Orléans, now that the alternative of the son of the duc de Guise had been suggested and therefore worked to keep her lover and his wife together. Catherine's security was further enhanced by the rivalry between Montmorency and Guise, whose attempts to introduce his daughter to the dauphin were a considerable threat to the Grand Maître's position.

An ordinance of 24 July 1534 authorised the raising of 6,000 soldiers from Picardie as a 'legion'. Montmorency was given the responsibility to raise this army, and issued commissions to the six gentleman who were to command the force. François personally inspected the raised force in an elaborate ceremony the following year. The legion would see much use in the following years, overall though the force proved ineffective and prone to ill discipline.

Departure from court

The Emperor sent the graaf van Nassau (count of Nassau) to France in October 1534 to present two proposals to the French. The first was that the duca di Milano (duke of Milano) should provide a pension to François' son Orléans in return for François renouncing his claim to Milano and Genoa. His second proposal was a marriage between the king's third son, the duc d'Angoulême and the king of England's daughter Mary. Montmorency, who received the proposals, dismissed the first out of hand, the Grand Maître writing a reaffirmation of France's claims over Milano to Nassau. Montmorency was however far less quick to dismiss the second proposal, and therefore the Emperor decided to take it further. François therefore dispatched Admiral Chabot to England with the latter proposal but received only counter-proposals from Henry and departed the country unsatisfied.

While the Emperor was occupied with his campaign into al-Ḥafṣiyūn controlled Tunis in June 1535, François did little to take advantage of his rival's absence. Montmorency had promised the Imperial ambassador that France would not exploit the Emperor's absence. Admiral Chabot and the war party at court were incensed, and Montmorency found it necessary to retire to Chantilly, leaving Chabot ascendent by default. François could have found himself in a diplomatically challenging position if he had followed the advice of the war party to attack while the Emperor was fighting the Muslims.

His departure was not however a disgrace, and he remained in all his titles and pensions. In October he oversaw the convening of the local Languedoc Estates. He conducted an inspection of the legion of the province and ensured Narbonne's fortifications were up to an appropriate standard.

After the French seizure of Savoia in early 1536, tensions skyrocketed with the Empire, northern Italy descending into an unofficial war. Chabot was made lieutenant-general of French controlled Piemonte. However Montmorency now returned to the centre of government, arriving on 7 May. Soon thereafter Chabot was removed as lieutenant-general of Piemonte, replaced by the marchese di Saluzzo (marquis of Saluzzo). Saluzzo would not long be the French lieutenant-general as he defected to the Empire on 17 May. Humières became the lieutenant-general of Dauphiné, Savoia and Piemonte, meanwhile the Emperor decided to invade Provence. A day after his decision to launch an invasion on 14 July Montmorency was made 'lieutenant-general' on both sides of the mountains with powers that included troop mobilisation, the command of the forces on the ground and the ability to negotiate peace.

Provence campaign

On 24 July 1536, an Imperial army, under the command of the Emperor invaded France from Italy, proceeding by the coast through Nice, crossing into the kingdom at Var. Concurrently an army under the graaf van Nassau invaded Picardie. Montmorency led the defence of the south, and François' attentions were focused in that direction. The king's council successfully convinced him not to lead the army, and leave it to the command of Montmorency. Montmorency's force assembled at Avignon, and by 25 July totalled 30,000 men. A month later this had ballooned to 60,000. Montmorency adopted a scorched earth strategy and devastated the lands of Provence to deny his enemy supply. He inspected the fortifications of Aix and Marseille and determining that Aix's were inadequate without at least a month's work and 6000 soldiers, he therefore had Aix evacuated. Marseille by contrast had recently been reinforced and had played a key role in the defeat of Bourbon's invasion in 1524, and therefore was not subjected to the destruction that was put upon Aix. The Emperor's goal was the capture of Marseille, and towards this end he captured Aix on 13 August. All roads to Marseille were blocked by French forces, and as his army sat near Aix it began to collapse to disease. The army was also in great want of food and water which they struggled to acquire in the devastated landscape. Foraging parties that sought to acquire food were sometimes set upon and butchered. By 2 September 1536, Montmorency estimated the Emperor had lost over 7000 men to dysentery and famine. The new dauphin Orléans (François' second son) received permission from François to join the army in the defence of Provence. By 11 September Charles decided to withdraw from Provence and Nassau made a similar decision up in Picardie around the same time. The invasions had been a failure. François joined the army at this time, but decided against ordering a pursuit, contenting himself to ordering a harassment of the retreating army by the light cavalry.

In the spring of 1537, Montmorency engaged in a campaign on the northern frontier of France, and was rewarded with great successes. The king had declared Artois, Vlaanderen and Charolais which he had ceded in the peace of Cambrai to be confiscated in January, and tasked Montmorency with advancing in the north. To this end Montmorency was made lieutenant-general with the responsibility to recover Saint-Pol and Artois. Montmorency and François captured Auxy-le-Château, then besieged Hesdin. On 6 May Saint-Pol was occupied by the royal army, threatening the Imperial supply line through Lens and Arras. Montmorency prepared to disband the army and send 10,000 soldiers to join Humières in Picardie. While demobilisation was ongoing, the Emperor launched a lightning offensive, threatening to surround Thérouanne. Saint-Pol and Montreuil fell quickly back to the Emperor. François dispatched Orléans the new dauphin to join Montmorency and conduct a counter-offensive, the young prince arriving in mid-June. A cavalry force under the duc de Guise also arrived to bolster the royal forces in Picardie. Montmorency was pleased with the effect the dauphin had on the army. In July they secured a favourable truce in the theatre and prepared to move south to where the war was continuing in Piemonte, Montreuil had been successfully regained and Thérouanne would remain in French hands; only the conquest of Saint-Pol had been reversed.

François had orchestrated a counter-offensive back into Italy in 1537, though with many troops tied up in other theatres it was limited in scope. A small army under the command of Humières, the lieutenant-general of French Piemonte had invaded Piemonte in April 1537 and made an unsuccessful attempt on Asti, and successful attempts on Alba and Cherasco. François secured a truce in the northern theatre thanks to the efforts of Montmorency and Orléans so that he might bring force to bear on Italy, in the meanwhile he urged Humières to hold firm and dismantle fortifications he could not hold. The Imperial commander del Vasto had little intention of waiting around for a new French army to show up, and began a counter offensive.

Entry into Piemonte

Montmorency arrived in Lyon, and was established by the king as the new lieutenant-general of French Piemonte. He had with him a force of 10,000 French infantry, 10,000 Italians, 14,000 Swiss, 12,000 landsknechts and 1,400 men-at-arms. The force was technically under the command of the dauphin Orléans, but Montmorency led the army in actuality. By this time, October, France only held Turin, Pinerolo and Savigliano in Piemonte, the towns were being besieged by del Vasto. Montmorency left Besançon on 23 October towards the pass de Susa which was held by Cesare Maggi with 6,000 men. Montmorency forced the passage. This success caused del Vasto to break off his sieges of the final French held towns and cities. The combined French army then began sieging back the towns of Piemonte, with François himself joining the army soon thereafter. He had by now had success in negotiations with the Emperor, and wanted to secure as much of Piemonte as possible prior to a truce coming into force. By November del Vasto had been compelled to retreat across the Po. On 27 November 1537 a three month truce was declared in Italy, del Vasto and Montmorency met to discuss the minutiae and agreed that each side would maintain in Italy the troops necessary to garrison their respective towns, and send other forces away.

This truce would last more than three months, being twice extended while the two sides argued over the specific arrangements of control that a more permanent peace settlement would entail in Italy. Montmorency and the Cardinal de Lorraine met with envoys of the Emperor at Leucate and agreed that the ducato di Milano would be given to the king's third son the duc de Angoulême as a dowry for his marriage to the daughter of the Emperor. However dispute arose between the king and Emperor over how many years the king would be able to administer the duchy for his son. Unable to achieve a consensus over the destiny of Milano, François and the Emperor compromised by agreeing to an extension of the truce for 10 years, during which time each side was to maintain what they currently possessed. Montmorency provided assurance that neither party would ever declare war over claims to Milano again. While the talks were ongoing, Montmorency directed a young Monluc, future Marshal of France to spy on the fortifications of Perpignan.

The king was greatly pleased with Montmorency, and met with him in Montpellier on 31 January 1538 to provide him his pay for the campaign, which totalled 158,000 écus, the court thronged around to celebrate him upon his entry to Lyon.

Ascendency

Constable

On 10 February 1538 several important appointments were declared by the king which benefitted the Montmorency family. His brother La Rochepot was appointed governor of the Île de France and therefore departed from his charge in Picardie. Most importantly however, Montmorency was established as Constable of France. The office had been left vacant since the treason of Constable Bourbon. In a ceremony on that day, ironically celebrated at a château that had once belonged to Bourbon, Montmorency was escorted by the sister of the king, the queen of Navarre from the king's private chambers to the great hall, where the king gave him the sword of the office. The Constable of France was the most senior commander of the French military, and he and the Marshals of France, whose concurrent number would total four by the 1560s held overall responsibility for France's land forces. On the battlefield the Constable outranked even princes du sang, and had the right to lead the vanguard even when the king was present. The most prestigious elements of the military under his authority were the gendarmerie of heavy cavalry, which was composed of ordinance companies of 30-100 men-at-arms. By this time, the French military possessed continually standing components, which greatly contributed to the kingdom's tax burden. The Constable also enjoyed advantageous apartments in the royal residence of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, right next to those of the king and queen. By this appointment, Montmorency effectively became lieutenant-general of the kingdom.

As Montmorency was ascending to the office of Constable he was no longer a Marshal, and therefore the king appointed two new Marshals, Claude d'Annebault and René de Montjean.

His elevation to the office of Constable was in part a reward for his leadership in the defence of France against the invasion of Provence that had been conducted in 1536. The great benefits he received from the king also felt like a victory to the dauphin, who saw them as a reward for his own successes on campaign, throughout which Montmorency and Orléans had become very close. During the campaign Orléans had undertaken an affair with Filippa Duci which had resulted in a pregnancy. Montmorency was informed of this and ordered that she be watched for the duration of the pregnancy, and kept the dauphin appraised with updates, filling the young man with pride. The child of this affair, Diane de France would first be married to the duca di Castro, grandson of Pope Paul III, with the marriage contract signed for the king by Montmorency, Aumale and the chancellor Olivier. The Pope committed to providing his grandson 200,000 écus to spend on land in France, and the ducato di Castro (duchy of Castro). After Castro's death, Diane would go on to marry Montmorency's eldest son.

Milano

In July of 1538, talks were conducted between the Emperor and king of France at Aigues-Mortes. For these important discussions Montmorency was among those granted an Imperial audience. The devolution of Milano to Angoulême was again discussed, in return for François committing France to a war against the Osmanlı İmparatorluğu. The two men agreed to co-operate going forward in the 'defence of Christendom' and reunification of the church behind Catholicism. Montmorency was delighted at the success of the meeting, which astonishing contemporaries insofar as the two bitter adversaries now appeared to be friends. While some at court were sceptical of this new friendship, Montmorency assured the court that the peace between the two men would last their entire lives. For his part, Montmorency ensured that France honoured the truce with the Empire.

Montmorency would be completely ascendent in the direction of French foreign policy for the next two years. His desire was to secure Milano for France, but through diplomatic means. All ambassadors wrote to him alongside the king. He recognised that to best achieve his goal, he needed to be in a position of strength with the Empire, and therefore sought to consolidate the French position in Piemonte and Savoia. Parlements and Chambre des comptes (chamber of accounts) were established in each of the occupied regions. Fortification was also undertaken of the key city of Piemonte, Turin, while the northern border was simultaneously fortified by Montmorency's brother La Rochepot.

As Constable of France, Montmorency was approached by foreign kingdoms that wished to do business with France. To this end in 1539 he received a request from the English court for the provision of 60,000 m of hemp fabric. This would have been sufficient to supply 100 great ships. In response it was 'diplomatically' protested that France lacked the capacity to fulfil such an order.

It was through the protection and patronship of Montmorency, that Saint-André received the charges of lieutenant-general and governor of Lyon in 1539.

Montmorency was again leaned upon for diplomatic purposes when François sought further peace talks with the Emperor in 1539. Montmorency organised the receptions for the Emperor which involved ceremonial entries into many cities as the Imperial party progressed through the country. The Emperor was received at the Château de Fontainebleau for Christmas. The Constable enjoyed his own apartments on the first floor at Fontainebleau. Upon the party's entry into Paris on 1 January 1540, the Emperor entered the city under a canopy, Montmorency proceeding him, holding the sword of his office aloft.

After some time together, Montmorency accompanied the Emperor back to the border, taking leave of the king at Saint-Quentin. Montmorency and the king's sons escorted the Emperor as far as Valenciennes. They brought back gifts from the town to the French court. It was generally assumed that Montmorency and the Cardinal de Lorraine would shortly be called to Bruxelles for a more formal deal, however the Emperor became distracted by the revolt of Ghent. Rumours began to swirl that the understanding between France and the Empire had broken down, which Montmorency derided as 'jealous talk'. In March the Emperor revealed that he had changed his mind about the provision of Milano as a dowry for François' third son. Instead, he suggested a dowry of Nederland, Bourgogne and the Charolais for the young prince. François would not receive Milano, and would have to withdraw from Piemonte and Savoia as part of this deal. Further, the lands would be administered under the Emperors' supervision and if his daughter María died without issue, the territory would revert to the Habsburg male line.

Path to disgrace

Upon receipt of this news François, Montmorency and Orléans locked themselves in a room for a long discussion. When it was concluded, Montmorency retired unwell to bed for several days. François delivered his reply to the Emperor in which he argued Nederland was a poor substitute for Milano which was his by right anyway. Moreover the instant gratification of Milano could not compare to a territory he would have to wait many years to receive. He later altered his reply to say that he would accept Nederland instead, but only if he received it immediately: the reversion clause could remain but only if Milano was given in compensation for the loss of Nederland. By June 1540 talks had collapsed entirely.

While still in a degree of favour, Montmorency engineered the disgrace of his long time enemy Admiral Chabot. Back in 1538 he enjoyed a position as the patron of the young duc d'Aumale who wrote to him that he might he was as much at Montmorency's command as were his own children. Aumale remained on positive terms with him in 1541 describing himself as Montmorency's 'very humble servant'. Aumale's father, the duc de Guise would remain cordial with Montmorency throughout the Constable's period of disgrace. In later years, Aumale would become the great rival of Montmorency as a favourite of the king in his capacity as the duc de Guise.

Around this time, Montmorency became aware his influence was beginning to slip with the king. In the hopes of buttressing his authority, he attempted to play upon François' hatred of subversion. To this end he shared with the king the sonnets of Vittoria Colonna (who was sympathetic to Protestantism), which he informed the king had been sent to his sister. However the queen of Navarre was able to gain the upper hand in this dispute. François continued to erode Montmorency's civic responsibilities, getting him to hand over the keys to the Louvre which he possessed in his capacity as Grand Maître.

In this first stage of his disgrace, he was removed from influence over diplomatic affairs, which were granted to Tournon. This removal occurred in April 1540, but he remained in overall favour with François who remarked that the Constable's only fault was that he did not 'love those who I love'. French foreign policy was now back in the hands of the war party at court, and François privately boasted of his plans for a new war against the Emperor.

On 11 October 1540, the Holy Roman Emperor decided to award the ducato di Milano (duchy of Milan) to his son the future Felipe II of España. Thus, François was to give up all his conquests in Italy, and reconstitute the defunct duché de Bourgogne which had been integrated into the royal domain as a dowry to be gifted by the Emperor to his son. François was enraged at the betrayal, and took out his frustrations on Montmorency. It was Montmorency, François alleged, who had allowed the Emperor to present this diplomatic embarrassment to him. Montmorency was forced to withdraw from court when the news arrived.

Not a month had passed since this news arrived in France than the king forbade his secretaries to use the cyphers Montmorency had provided them. Montmorency, believing himself disgraced, asked François for permission to retire from court but François told him he still had use of his services. Indeed he staged something of a revival in his fortunes in early 1541, with the Imperial ambassador reporting that his credit had increased. It was ephemeral, by April he was reported to be at the mercy of the king's mistress, the duchess d'Étampes at court, his credit decreasing daily. Fully aware of this, Montmorency advised the lieutenant-general of Piemonte Langey to send his correspondence to Marshal Annebault in future.

In June 1541 the king humiliated Montmorency through a request he made at the wedding of Jeanne d'Albret, the daughter of the queen of Navarre and the herzog von Jülich-Cleves-Berg (duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg). Jeanne refused (or was unable) to walk to the altar for the ceremony, and therefore the king commanded Montmorency to carry her to the altar. The court was shocked that such a high ranking man as Montmorency had been ordered to undertake such a demeaning task, and Montmorency remarked to his nearby friends 'this is the end of my favour, I am saying goodbye to it'. The day after the wedding, he left court, and would not return during the lifetime of François.

Disgrace

Governate revoked

On 21 May 1542, François abolished all governorships in France, and ordered the people of France not to obey their ex-governors' commands. He justified this on the grounds that their powers had become excessive. In the following weeks he proceeded to re-appoint every former governor of the provinces with the exception of Montmorency who was replaced in Languedoc. The initial abolition is therefore understood to be an attack on Montmorency disguised in a general dismissal due to his power making a specific dismissal unfeasible politically.

With his disgrace, Montmorency was no longer able to protect his political clients - this led to the disgrace of the chancellor of France Poyet in 1542. Conversely, Admiral Chabot was rehabilitated, and returned to a central place at the French court.

Dauphin's party

During his time of disgrace Montmorency was absent from the court. However, he remained close with the dauphin the duc de Bretagne (formerely the duc d'Orléans), while the duc d'Orléans (formerly the duc d'Angoulême) allied himself with the king's mistress the duchesse d'Étampes. Also in the faction of the dauphin were the queen and most of the French cardinals. Bretagne would ask the king to recall Montmorency so that he could serve with him in the campaigns against the Imperials, however this was refused. With Bretagne and Orléans in opposition to one another, each man represented a centre of their respective faction; this dynamic would however be radically altered by the sudden death of Orléans in 1545. Bretagne felt keenly the absence of his mentor from the centre of power.

These years would be ones of retirement for the Constable, and it was only with the death of the king that he returned to holding political influence himself. As early as 1546, Bretagne began to anticipate his coming reign, and to this end, planned the division of offices that would go to his various favourites upon his ascent. Montmorency would be recalled from disgrace, Saint-André made Premier Chambellan (first chamberlain) and Brissac established as Grand Maître de l'artillerie (grand-master of the artillery). Reports of these speculative appointments was delivered to François by the court jester, and he flew into a rage when he heard of his son's presumptuousness. He advanced on his son's chambers with the captain of his Scots guard and broke the door down, finding no one inside he had the furniture destroyed. Shortly thereafter the remaining partisans of Bretagne were expelled from the court.

Not all those who allied with Bretagne in the final years of François' reign were to profit as completely as Montmorency and Saint-André. Another favourite, Dampierre ended in the dauphin's disgrace for daring to attack his mistress Diane de Poitiers, others died in battle or judicial duels.

As he lay dying, François summoned Bretagne to his bedside. Father implored son not to recall Montmorency from his disgrace, and to trust in the men the king had surrounded himself with since 1541, chief among them Tournon and Annebault.

Return to the centre

Palace revolution

François I of France died around 14:00 on 31 March 1547. While those in the room were still mourning, the dauphin Bretagne, now styled King Henri II dashed off letters summoning Diane and Montmorency to come to court. Montmorency's recall was therefore rapid, and he was invited to join Henri at Saint-Germain. The two engaged in a 2 hour conference on 1 April during which Montmorency and the king engaged in a complete reorganisation of the government. After the meeting Montmorency received the apartments of François' former mistress the duchesse d'Étampes at Saint-Germain. Holding court here, he received the flocks of condolences that poured in for the recently departed king.

Montmorency assumed the position that had been jointly occupied by Admiral Annebault and Cardinal de Tournon in leading the administration of François in the king's final years. Both men were dispossessed of their charges that evening. Annebault was allowed to remain Admiral, however he would no longer be paid, in much the same way as Montmorency had maintained his charge of Constable without pay during his disgrace. He was further obliged to surrender his Marshal office to Saint-André. Montmorency became commander of the royal armies and the lynchpin of the royal council almost immediately. His proximity with the new king was such that he even shared the king's bed on occasion during 1547, a practice which shocked some contemporaries. The ambassador of Ferrara remarked on the matter with revulsion. His establishment as head of the administration was represented by his resumption of the offices of Constable and Grand Maître which he had enjoyed in former years. The duchesse d'Étampes, enemy of both Montmorency and Henri was banished from court. Montmorency also received the arrears of pay he would have been owed if not for his disgrace.

With great pride Montmorency remarked on a different incident of intimacy with the king where Henri had entered his chambers while he was receiving a footbath. The Constable bragged about the event to Saint-André, who in turn told the duc d'Aumale. According to the ambassador of Ferrara, Aumale was mortified, keenly aware the king would never make such shows of intimacy with him. One of the king's favourite horses, Compère was a gift from Montmorency.

Montmorency was restored to the governate of Languedoc, and his brother La Rochepot was restored to his office as governor of the Île de France and Paris. His eldest nephew Cardinal de Châtillon received rich new benefices among them Beauvais. Montmorency received the charge for the second time on 12 April 1547. Keen to reward his favourite, the return of his governate came with back-pay for the years in which he had been denied his possession of Languedoc, totalling 100,000 écus in addition to the annual income of 25,000 écus he would receive going forward. In sum Henri distributed 800,000 livres among his three great favourites (Montmorency, Aumale, and Saint-André) upon his ascent, which was raised by a tax of two tenths upon the clergy.

On 12 April the king received Montmorency's oath in his capacity as Constable of France, with the king declaring that all civil and military officials were to be subordinated to him. He also restored the exercise of his old lesser charges, that of captain of the forts of Bastille, Vincennes, Saint-Malo and Nantes.

Until at least 1552, all ambassadors to France presented their credentials to Montmorency before they were received by the king.

Back in favour, Montmorency advanced his nephews once more, with Coligny being elevated to the position of colonel-general of the French infantry within a month of Henri's accession. Over the following years of Henri's reign, Coligny would be made Admiral of France, governor of Picardie and governor of the Île de France. Through advancement of his nephews Montmorency secured his own power.

At the centre of power once more, Montmorency was again able to be a distributor of royal favour to a network of patronage. As such he was soon approached by the queen of Navarre who was seeking to re-enter royal favour. The two had a frosty relationship. This meant that when in 1548 the king became suspicious that the queen and her husband the king of Navarre were intriguing with the Emperor, Henri turned to Montmorency, who had his agents intercept all mail addressed to the couple for several months. In 1556 suspicions would again arise at court as to the potentially treasonous actions of the new king of Navarre and his wife with the Emperor over Spanish Navarre. The king of Navarre wrote to Henri and Montmorency, hoping to recharacterize his dealings in a less dangerous light. The queen of Navarre wrote to Montmorency separately, urging him to maintain the good relations he enjoyed with Navarre.

Push for war

Despite the centrality of his position in the new administration, Montmorency was unable to make the king forget the captivity he had experienced in Imperial hands in prior years. Henri was keen to exert himself against the Empire and therefore summoned the Holy Roman Emperor to appear at his coronation in his capacity as the comte de Flandre, formerly a vassal of the French crown. The Emperor replied that he would attend the coronation, at the head of an army of 50,000 men. Montmorency, who desired peace with the empire, was tasked with reinforcing the garrisons on the border.

Henri's coronation did not immediately follow his father's death, it no longer being seen as the ceremony by which royal power was conferred. Therefore, it was not until 25 July 1556 that it was undertaken. The next day, representatives of the four most ancient baronies of France went to receive the ampulla of sacred oil that would be used to anoint the king. The Montmorency who represented one of the four baronies were represented by the Constable's eldest son as the Constable was required elsewhere. During the coronation, Henri awarded two collars of the Ordre de Saint-Michel (Order of Saint-Michel), the highest order of French chivalry. One was granted to the Italian condotierri Piero Strozzi, while the other was awarded to Montmorency's nephew Coligny.

Montmorency also ensured that gentlemen were not left in a state of discontent with the crown where possible. To this end he assured such figures received a caress or embrace from the king, which he advised would appease their discontent. According to Brantôme, if such a system worked at this time, it broke down by the time of the Wars of Religion.

On 26 June 1547 Henri created a new law applying to the frontier provinces of the east. The border was to be divided into three zones of control, each subordinated to a Marshal of France. The Marshal would have all the authority over troops in their region, depriving the governors of the provinces. Montmorency, as the authority above the Marshals would therefore have military authority over all eastern border provinces. The motivation for this new policy, though it was a dead letter on arrival, was to invest authority in Montmorency and the three Marshals (Saint-André, Bouillon and Melfi) all of whom were favourites of the new king, at the expense of the Lorraine and Clèves family who were governors of those regions.

Coup de Jarnac

At the start of Henri's reign a celebrated duel exposed the factions that were to dominate the reign of the young king. La Châtaignerie and Jarnac were granted permission to conduct a judicial duel by the king. It was the first judicial duel that had been authorised in France since the times of Louis IX. Diane and the Lorraine family acted as patrons to La Châtaignerie, while Montmorency took Jarnac (formerly a member of the duchesse d'Étampes' party during the reign of François) under his wing. Jarnac's second would be Claude de Boisy, a friend of Montmorency's. Crowds gathered for the duel, which featured hundreds dressed in satin. In a shock to many of the watchers, Jarnac was able to deliver a quick victory in the duel getting around his opponent and slicing him in the back. The king was stunned, and for a while did not respond to Jarnac's request to have his honour restored and opponent spared. Marguerite and Montmorency urged Henri to speak so that La Châtaignerie's life could be spared. Henri eventually spoke, but did not say the customary plaudit to the victor that he was a man of honour. La Châtaignerie humiliated by his defeat tore off the bandages provided to him and bled out. Montmorency was the main winner of the duel, seen as wise for his backing of Jarnac. Henri meanwhile vowed to never allow another judicial duel during his reign.

Saint-André had suffered disgrace during the reign of François for his allegiance to Henri, however he was richly rewarded upon his patron's rise to power. He was made a Marshal and premier gentilhomme de la chambre du roi (first gentleman of the king's chamber) which gave him access to the king at times when even Montmorency was precluded from being in his presence.

Valentinois' party

The king's mistress Diane de Poitiers, duchesse de Valentinois, seeking a counterbalance to the great influence over the king that Montmorency enjoyed, found it in the patronage of the Lorraine family, and in particular the duc d'Aumale and archbishop of Reims. She and the Lorraines had been in friendly conversation since at least 1546 when a marriage was arranged between the marquis de Maine and her daughter Louise de Brézé. The family achieved a major coup in 1548 when they secured a promise of marriage between the four year old dauphin and their six year old niece Mary Stuart. This marriage would come to pass on 24 April 1558. The alliance of the Lorraine family and Diane began to erode Montmorency's power, much to his consternation. In opposition to this, he frequently tried to contrive reasons for the Lorraine brothers to be absent from court. Ultimately, the Lorraine brothers would not attain the level of intimacy that Montmorency enjoyed with Henri.

In the rivalry between Montmorency and the Lorraines during the reign of Henri, Saint-André maintained a flexible position between the two, ready to follow whichever advantaged him most in the particular circumstances. Saint-André would however have a rivalry with Montmorency's nephews for access to military command.

In 1548 the Venetian ambassador reported that it was a matter of dispute at the court which of Diane and Montmorency, Henri loved more.

Royal council

During the reign of François a conseil des affaires (council of affairs), sometimes called the secret council had been established. It would meet with the king every morning and was composed of the leading royal favourites, Montmorency, Saint-André, the Lorraine brothers, the elder Cardinal de Lorraine, the king of Navarre, the duc de Vendôme, Marshal Bouillon and some administrative royal functionaries who did not participate in the discussions proper. Through this council, royal police was decided upon. In the most sensitive discussions, only Montmorency, Saint-André and the Lorraine brothers would be invited. In the afternoon the conseil privé (privy council) convened to consider matters of finance and administration. Legal matters that had been referred to the king could also be settled during the course of its sessions. It was a far larger council, and could meet without the presence of the king himself.

The two families, Lorraine and Montmorency dominated Henri's councils. Aside from the direct members of the families on the council, such as Montmorency's nephew Odet de Coligny their respective 'creatures' filled the body. Montmorency and the Chancellor François Olivier enjoyed a close relationship, unified by their antipathy for the Lorraine family. For example, Jean de Morvillier the bishop of Orléans, and Louis de Lausignan, the seigneur de Lanssac were both men of Montmorency's faction on the court. However affiliation was not binary between the families, and men such as Jean de Monluc, the bishop of Valence maintained relationships with both families. While Montmorency enjoyed the most senior position on the royal council, the Cardinal de Lorraine held the second most senior position. The king for his part was not particularly interested in domestic politics and was content to balance the networks of his favourites in the administration while they ran things.

On 1 April 1547 letters patent established a new royal secretariat, that of the secrétaire d'État (secretary of state), which was grafted onto the former office of secrétaire des finances. The letters patent were likely drawn up by Montmorency himself. Montmorency also enjoyed the benefit of having one of Henri's four secretaires d'État, Jean du Thier, being an old client of his. Indeed Montmorency had gained for Thier the position of secrétaire du roi (secretary of the king) in 1536 and the secretary had served as his personal secretary since 1538. Du Thier was his own man however, and by his appointment in 1547 he was willing to work equally with the Cardinal de Lorraine and over the following decade would depart from Montmorency's service to be firmly associated with the duc de Guise. Three of the four initial secretaries established to the office in 1547 were the picks of Montmorency, and they generally leaned towards him, as they favoured a similarly peaceful international policy as opposed to the Lorraine war policy. The four secretaries did not however have the privilege of opening diplomatic dispatches addressed to the king, at least early in Henri's reign, before the grandees became occupied with war. Montmorency took responsibility for this personally from 1547, both due to his assiduous nature and his desire to maintain his centrality in the court. In 1552, the secrétaires d'État were joined by a new office, that of messieurs des finances. Both these roles were subordinate to the authority of Montmorency, who acted as something like a prime minister.

The grandees of the court, and in particular Montmorency, frequently took advantage of the secretaries to provide either the postscript or closure to the correspondence he was dispatching on his own account. On occasion the secretaries would write the entire letter for Montmorency.

In their later biographies, Marshal Tavannes and Marshal Vielleville would both characterise Henri as a passive presence during his own reign. For Tavannes, it was in fact the reign of Montmorency, Diane and the Lorraine brothers. Vielleville described the various grandees (adding Saint-André to Tavannes' list) as 'devouring the king like a lion'. Whether this distance from rule was a choice of the king is debatable, Montmorency was accused of keeping the king out of involvement in government to better allow for his total control. This included only showing him a portion of the correspondence the court received. It was also true that Henri's long running dispute with his father had meant that he had been kept out of the decision making processes of state for much of his adult life, and therefore he looked for guidance from a man with far more experience. It is possible even that Montmorency represented a surrogate father figure for a man so long estranged from his own. The Italian ambassador at one point remarked that the king trembled when Montmorency approached "as children do when they see their schoolmaster".

A reflection of this balance can be seen in the awards of office made by the royal council. When such awards were signed off on by the king, the supporting grandee would be indicated as 'present'. Of the 109 awards made in spring 1553, 11% had the backing of the duc de Guise while 10% had the backing of Montmorency.

Italian expedition