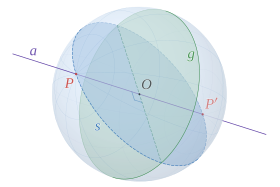

In mathematics, two points of a sphere (or n-sphere, including a circle) are called antipodal or diametrically opposite if they are the endpoints of a diameter, a straight line segment between two points on a sphere and passing through its center.

Given any point on a sphere, its antipodal point is the unique point at greatest distance, whether measured intrinsically (great-circle distance on the surface of the sphere) or extrinsically (chordal distance through the sphere's interior). Every great circle on a sphere passing through a point also passes through its antipodal point, and there are infinitely many great circles passing through a pair of antipodal points (unlike the situation for any non-antipodal pair of points, which have a unique great circle passing through both). Many results in spherical geometry depend on choosing non-antipodal points, and degenerate if antipodal points are allowed; for example, a spherical triangle degenerates to an underspecified lune if two of the vertices are antipodal.

The point antipodal to a given point is called its antipodes, from the Greek ἀντίποδες (antípodes) meaning "opposite feet"; see Antipodes § Etymology. Sometimes the s is dropped, and this is rendered antipode, a back-formation.

Higher mathematics

The concept of antipodal points is generalized to spheres of any dimension: two points on the sphere are antipodal if they are opposite through the centre. Each line through the centre intersects the sphere in two points, one for each ray emanating from the centre, and these two points are antipodal.

The Borsuk–Ulam theorem is a result from algebraic topology dealing with such pairs of points. It says that any continuous function from to maps some pair of antipodal points in to the same point in Here, denotes the -dimensional sphere and is -dimensional real coordinate space.

The antipodal map sends every point on the sphere to its antipodal point. If points on the -sphere are represented as displacement vectors from the sphere's center in Euclidean -space, then two antipodal points are represented by additive inverses and and the antipodal map can be defined as The antipodal map preserves orientation (is homotopic to the identity map) when is odd, and reverses it when is even. Its degree is

If antipodal points are identified (considered equivalent), the sphere becomes a model of real projective space.

See also

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Antipodes" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–34.

- V. Guillemin; A. Pollack (1974). Differential topology. Prentice-Hall.

to

to  maps some pair of antipodal points in

maps some pair of antipodal points in  Here,

Here,  -dimensional sphere and

-dimensional sphere and  sends every point on the sphere to its antipodal point. If points on the

sends every point on the sphere to its antipodal point. If points on the  -space, then two antipodal points are represented by additive inverses

-space, then two antipodal points are represented by additive inverses  and

and  and the antipodal map can be defined as

and the antipodal map can be defined as  The antipodal map preserves

The antipodal map preserves