Antoine-Jacques Roustan (23 October 1734 – 15 June 1808) was a Genevan pastor and theologian, who engaged in an extensive correspondence with Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Unlike Rousseau, he believed that a Christian republic was practical - that the Christian religion was not incompatible with patriotism or republicanism.

Life

Roustan was born on 23 October 1734 in Geneva, the son of Jacques Roustan, a Protestant shoemaker and Marie Baile. He studied theology at Geneva, and was ordained a minister in 1759. In 1761 he married Jeanne-Françoise, daughter of Justus Saint-Andre, a barber. He was a schoolteacher and minister of St. Evangile in Geneva from 1761–1764, when he became pastor of the Swiss Church of London (1764–1791). In 1791 he became a "bourgeois" (gentleman) of Geneva, and in 1792 became a pastor in Geneva, and from 1797-1798 he was a headmaster. He was elected a Member of the Council of Two Hundred in 1793. Roustan and his friend the Rev. Jacob Vernes wrote a History of Geneva, which remained in manuscript form. He published several books on Christianity and Deism.

Correspondence with Rousseau

Roustan exchanged many letters with Rousseau between 1757 and 1767. In his first letter of March 1757 he compared Rousseau to Socrates. Rousseau praised him in return, but, although polite about the poetry he had sent, advised him against seeking a career as a man of letters. Roustan wrote to Rousseau after reading Julie, or the New Heloise (1761) saying that although he found the novel delightful, he was concerned that it was immoral in describing adulterous love so vividly and in describing hope as the only reason to believe in Christianity. He visited Rousseau in Môtiers in 1762 and welcomed in him in London in 1766, but retained his views on the compatibility between Christianity and patriotism.

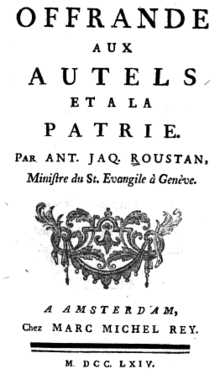

Four of his works – Défense du christianisme considéré du côté politique, wherein he refuted some of Rousseau's arguments from On the Social Contract; Discours sur les moyens de réformer les mœurs; Examen des quatre beaux siècles de Voltaire; and Dialogue entre Brutus et César aux Champs Élysées – were collected and published in 1764 under the title Offrande aux autels et à la patrie. The rebuttal in Défense du Christianisme ou réfutation du chapitre VIII du Contrat Social is friendly, and in fact Rousseau approved of his work and helped him with finding a publisher. In it Roustan implied that Rousseau may not himself have believed in his stated view that the scriptures preach servitude and resignation, and went on to say that doing good works was an integral part of the religion, including fighting for freedom and against tyranny. He therefore felt that Christianity and Republicanism or patriotism were fully compatible.

In 1776 Roustan published a rebuttal to Rousseau's Profession of Faith of a Savoyard Vicar in Emile: or, On Education. His Examen critique de la seconde partie de la "profession de foi du Vicaire Savoyard" was one of the main reasons that Rousseau was mocked by Voltaire in Voltaire's Remontrances des pasteurs du Gévaudan.

Bibliography

- Antoine Jacques Roustan (1764). Offrande aux autels et à la patrie: Contenant Défense du christianisme ou réfutation du chapitre viii du Contrat social. Examen historique des quatre beaux siécles de Mr. de Voltaire. Quels sont les moyens de tirer un peuple de sa corruption. M. M. Rey.

- Antoine Jacques Roustan (1768). Lettres sur l'etat present du Christianisme: et la conduite des incredules. Chez C. Heydinger ... et se vend chez P. Elmsley.

- Antoine Jacques Roustan (1768). Briefe über den heutigen Zustand des Christenthumes und das Betragen der Ungläubigen.

- Antoine-Jacques Roustan (1771). Réponse aux difficultez d'un théiste, ou supplément aux lettres sur l'état présent du christianisme: à quoi l'on a joint un sermon sur la révocation de l'Édit de Nantes. T. Brewman.

- Antoine Jacques Roustan (1773). L'impie démasqué. Ou remontrance aux écrivains incrédules. chez C. Heydinger.

- Antoine Jacques Roustan (1776). Examen critique de la seconde partie de la Confession de foi du vicaire savoyard.

- Antoine-Jacques Roustan (1783). Catéchisme raisonné.

- Antoine Jacques Roustan (1784). Abrégé de l'histoire moienne: par A.J. Roustan, ... imprimé par Baker et Galabin.

- Antoine-Jacques Roustan (1790). Abrégé de l'histoire universelle. chez Desray.

- Antoine Jacques Roustan (1793). A catechism upon a new and improved plan. Printed by W. Eyres.

Footnotes

- "Plus je me repasse en revue, et plus je trouve que je suis tout pétrifié de Socrate; lui et vous faites meme histoire, et en vérité nous sommes si Athéniens que nous meritons bien d'en avoir un." (Leigh 1998, pp. 165)

References

- ^ Candal 2010.

- Touchefeu 1999, pp. 198.

- Cranston 1991, pp. 263.

- ^ BiographieUniverselle 1846, pp. 140.

- ^ Quérard 1836, pp. 246–247.

- Rosenblatt 1997, pp. 264–265.

- Touchefeu 1999, pp. 358.

Sources

- "ROUSTAN (Antoine-Jacques)". Biographie universelle ou Dictionnaire de tous les hommes qui se sont fait remarquer par leurs écrits, leurs actions, leurs talents, leurs vertus ou leurs crimes, depuis le commencement du monde jusqu'a ce jour (in French). Vol. 17 Ritzon – Scheremetof. Brussels: H. Ode. 1846.

- Candaux, Jean-Daniel (2010). "Roustan, Jacques-Antoine". Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, Bern (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- Cranston, Maurice William (1991). The noble savage: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1754–1762. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-11864-2.

- Leigh, R. A., ed. (1998). Correspondance complète de Jean Jacques Rousseau: édition critique. Publications de l'Institut et musée Voltaire (in French). Vol. 4. Institut et musée Voltaire.

- Quérard, Joseph Marie (1836). "ROUSTAN (Antoine-Jacques)". La France littéraire: ou Dictionnaire bibliographique des savants, historiens et géns de lettres de la France (in French). Vol. 8. Firmin Didot père et fils.

- Rosenblatt, Helena (1997). "The Social Contract". Rousseau and Geneva: from the first discourse to the social contract, 1749–1762. Ideas in context. Vol. 46. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57004-6.

- Touchefeu, Yves (1999). L'antiquité et le christianisme dans la pensée de Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Studies on Voltaire and the eighteenth century (in French). Vol. 372. Voltaire Foundation.