| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Arthropod mouthparts" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Mouthparts of Mandibulata and Chelicerata

Mouthparts of Mandibulata and Chelicerata

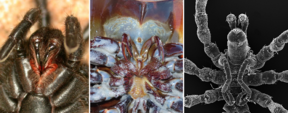

The mouthparts of arthropods have evolved into a number of forms, each adapted to a different style or mode of feeding. Most mouthparts represent modified, paired appendages, which in ancestral forms would have appeared more like legs than mouthparts. In general, arthropods have mouthparts for cutting, chewing, piercing, sucking, shredding, siphoning, and filtering. This article outlines the basic elements of four arthropod groups: insects, myriapods, crustaceans and chelicerates. Insects are used as the model, with the novel mouthparts of the other groups introduced in turn. Insects are not, however, the ancestral form of the other arthropods discussed here.

Insects

Main article: Insect mouthpartsInsect mouthparts exhibit a range of forms. The earliest insects had chewing mouthparts. Specialisation includes mouthparts modified for siphoning, piercing, sucking and sponging. These modifications have evolved a number of times. For example, mosquitoes and aphids both pierce and suck; however, female mosquitoes feed on animal blood whereas aphids feed on plant fluids. This section provides an overview of the individual mouthparts of chewing insects. The diversification of insects' food sources led to the evolution of their mouthparts. This process was facilitated by natural selection.

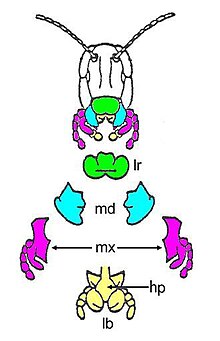

Labrum

Main article: Labrum (arthropod mouthpart)The labrum is a flat extension of the head (below the clypeus), covering the mandibles. Unlike other mouthparts, the labrum is a single, fused plate (though it originally was—and embryonically is—two structures). It is the upper-most of the mouthparts and located on the midline. It serves to hold food in place during chewing by the mandibles and thus can simply be described as an upper lip.

Mandible

Main article: Mandible (arthropod mouthpart)Chewing insects have two mandibles, one on each side of the head. They are typically the largest mouthpart of chewing insects, being used to masticate (cut, shred, tear, crush, chew) food items. They open outwards (to the sides of the head) and come together medially.

Maxilla

Main article: Maxilla (arthropod mouthpart)Paired maxillae cut food and manipulate it during mastication. Maxillae can have hairs and "teeth" along their inner margins. At the outer margin, the galea is a cupped or scoop-like structure, which sits over the outer edge of the labium. They also have palps, which are used to sense the characteristics of potential foods.

Labium

Main article: Labium (insect mouthpart)The labium is a single structure, although it is formed from two fused secondary maxillae. It can be described as the floor of the mouth and functioning in close the mouth of the insect. With the maxillae, it assists manipulation of food during mastication.

Hypopharynx

The hypopharynx is a somewhat globular structure, arising from the base of the labium. It assists swallowing. It performs the role of the tongue found in large vertebrates.

Myriapods

Myriapods comprise four classes of arthropod, each with a similar morphology: Class Chilopoda (centipedes); class Diplopoda (millipedes); class Pauropoda; and class Symphyla. Myriapod mouthparts are similar to those of chewing insects, although there is some variation between the myriapod classes. A labrum is present but sometimes is not obvious and forms an upper lip, often in association with an epistome. The labium is formed by first maxillae in diplopoda forming the gnathochilarium. The preoral cavity so-formed contains paired mandibles and any maxillae which are present.

Forcipules

Centipedes, in addition to their mouthparts, possess a pair of "poison claws", or forcipules. These, like the maxillipeds of crustaceans, are modified legs and not true mouthparts. The forcipules arise from the first body segment, curving forward and to the midline. The tip is a pointed fang, which has an opening from a venom gland. The forcipules are used to capture and envenomate prey.

Crustaceans

Crustaceans comprise a number of classes, with various feeding modes supported by a range of adaptations to the mouthparts. In general, however, crustaceans possess paired mandibles with opposing biting and grinding surfaces. The mandibles are followed by paired first and second maxillae. Both the mandibles and the maxillae have been variously modified in different crustacean groups for filter feeding with the use of setae.

Maxillipeds

Up to the first three pairs of legs are modified to maxillipeds, which assist manipulation of food items by passing food forward to the mandibles for chewing or to the maxillae for cutting into smaller pieces.

Setae

Filter feeding crustaceans have setae on modified appendages that act as filters. Filter feeding may have developed in association with swimming, with early morphological adaptations occurring on the appendages of the body trunk. Subsequent adaptations appear to have favored forward filtering appendages. Filtering appendages generate water currents that bring food items into reach for collection by setae. Other setae may be used to brush the filtering setae clean, and yet other setae may transport food items to the mouth.

Cirri

Barnacles have thoracic appendages modified for feeding, the cirri, which filter suspended food particles from water currents and pass the food to the mouth.

Chelicerates

Chelicerates comprise four classes of arthropod, with similar gross morphology but defining differences: Class Xiphosura (horseshoe crabs); class Eurypterida (the extinct eurypterids); class Arachnida (spiders, scorpions, ticks and mites); and class Pycnogonida (sea spiders). Chelicerates are in part defined by possessing chelicerate appendages, although crustaceans also possess chelate appendages. Chelicerates are more easily distinguished from other arthropods in lacking antennae and mandibles.

Chelicerae

Chelicerae are chelate appendages that are used to grasp food. For example, in horseshoe crabs, they are like pincers, whereas in spiders, they are hollow and contain (or are connected to) venom glands and are used to inject venom to disable prey prior to feeding. In some spiders, the chelicerae have teeth, which are used to macerate prey items to assist digestion by secreted enzymes. Those spiders without toothed chelicerae inject digestive enzymes directly into their prey. Mites and ticks have a range of chelicerae. Carnivores have chelicerae that tear and crush prey, whereas herbivores can have chelicerae that are modified for piercing and sucking (as do parasitic species). In sea spiders, the chelicerae (also known as chelifores) are short and chelate and are positioned on either side of the base of the proboscis or sometimes vestigial or absent.

Proboscis

Sea spiders possess a tubular proboscis forward from the body trunk, at the end of which is the opening to the mouth. In those species that lack chelifores and palps, the proboscis is well developed and more mobile and flexible. In such cases, it can be equipped with sensory bristles and strong rasping ridges around the mouth.

See also

References

- ^ Krenn, Harald W. (2019), "Form and Function of Insect Mouthparts", Insect Mouthparts, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 9–46, ISBN 978-3-030-29653-7, retrieved 2024-05-22

- Rowland Shelley & Paul Marek (2005-03-01). "Centipedes: general information". East Carolina University. Archived from the original on 2004-09-11.