The Atari CX40 joystick was the first widely used cross-platform game controller. The original CX10 was released with the Atari Video Computer System (later renamed the Atari 2600) in 1977 and became the primary input device for most games on the platform. The CX10 was replaced after a year by the simpler and less expensive CX40. The addition of the Atari joystick port to other platforms cemented its popularity. It was the standard for the Atari 8-bit computers and was compatible with the VIC-20, Commodore 64, Commodore 128, MSX, and later the Atari ST and Amiga. Third-party adapters allowed it to be used on other systems, such as the Apple II, Commodore 16, TI-99/4A, and the ZX Spectrum.

The CX40 was so popular during its run that it became as iconic to Atari as the company's "Fuji" logo; it remains a common staple in video game iconography to this day, and is commonly referred to as the symbol of 1980s video game system design. The CX40 has been called "the pinnacle of home entertainment controllers in its day", and remains a staple of industrial design discussions.

The CX40 had several well-known problems and was subject to eventual mechanical breakdown. A number of more robust third-party alternatives were available in a thriving market, but generally at much higher prices so they never achieved widespread popularity in comparison to the CX40.

The Atari-style joystick declined in popularity as games relied on multiple buttons for gameplay. Systems from the third generation of video game consoles, such as the Nintendo Entertainment System and Master System included two action buttons on their controllers (with the NES controller also including two menu buttons). Atari's own Atari 7800 shipped with two-button controllers as well.

Description

The Atari joystick works by connecting the ground pin to one of several pins in the Atari joystick port, thereby dropping the voltage on that pin and creating a signal that can be noticed by a controller in the computer. For this reason, Atari-style joysticks are sometimes referred to as "digital joysticks", largely to differentiate them from the analog joysticks found on systems like the Apple II and IBM PC.

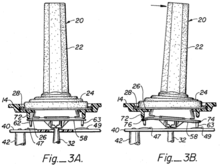

The main structure of the CX40 is formed from a concave moulded thermoplastic base with a separate flat lid that covers the opening on the top of the base. Four cylindrical protrusions on the inside of the base hold a printed circuit board (PCB) above the bottom, roughly centered vertically. A conical post on the base passes vertically through a hole in the middle of the PCB.

The PCB has five membrane switches mounted on top. Four of the switches are arranged in a cross pattern around the hole in the middle of the PCB; the fifth is offset near one of the corners. The PCB connects the switches to pins in the 9-pin D-connector that leads to the console via a cutout in the upper right corner of the base. The cutout is shaped to grip a moulded strain relief on the cable.

The stick itself is a moulded polypropylene form consisting of a hollow vertical cylinder with a hemispherical dome at one end. The stick is placed on top of the conical post in the base, and the lid is placed over it. This clamps the stick between the post and the circular cutout in the lid. When pressure is applied to move the stick, it can rotate on the post by sliding the hemisphere within the circular cutout.

The hemisphere has four small "fingers" at the bottom, which are positioned to lie over the switches on the PCB. Cutouts in the hemisphere make the fingers mechanically separate from the main section of the stick, allowing them to flex so they do not press too hard on the switches. When the stick is moved, the hemisphere rotates on its support post, bringing the fingers down to press on the appropriate buttons. At the same time, the opposite side of the hemisphere rises, where it comes into contact with short protrusions on the lid. These push down on the flexible section of the hemisphere, providing a centering force that returns the stick to the upright position when pressure is released.

The stick is assembled by placing the PCB within the lower case and routing the cable out of the box. The stick is then placed on top of the post, and a flexible rubbery cover is placed over the stick. A red plastic button is placed over the fifth switch, providing the fire button; and the top lid is then placed on top of the entire assembly. Four machine screws inserted from the bottom of the case through the PCB support protrusions hold the lid on, holding everything in place through compression.

Although the stick can be pressed in any direction, the four fingers on the hemisphere allow only two switches to be pressed at a time. This allows a total of eight directions: four for up, down, left. and right, and four more for combinations of neighboring switches: up-left, up-right, down-left, and down-right. The physical movement on the post prevents non-neighbouring switches from being pressed; one can not press up and down at the same time, for instance.

The base and its cover are moulded with some roughness in the plastic. The portion directly around the stick and the fire button are smooth. Just around the opening for the stick are a series of rectangular embossings with the four cardinal directions indicated by small wedge shapes. The 12 o'clock position replaces the wedges with the word "TOP". These markings are all painted orange, but this tends to wear off over time.

Problems

Right-handed users would normally hold the stick in their left hand by gripping the left side of the case with their thumb over the fire button, and fingers wrapped around the left side and bottom, while their right hand operated the stick. Some games allowed the stick to be rotated for left-handed users, or this could be done with some minor re-wiring.

The ergonomics of the base and the need to hold it while pressing the fire button led to fatigue of the left thumb that became known as "joystick thumb". This was especially common in games that required the user to fire repeatedly or hold down the button for long periods, like Eastern Front (1941). This led to various "autofire" attachments, available as do-it-yourself plans, pre-assembled, or as parts of 3rd party sticks. These simulated rapid presses of the fire button as long as the button on the stick was held down.

Small rubbery pads on the bottom allowed for stick placement on a desktop. However, the torque needed to operate the internal switches was more than enough to flip over the lightweight stick. Some 3rd party replacements used a much larger base and/or a shorter vertical stick so the torque was reduced. Generally those with bases large enough for one-handed use tended to be too large to use two-handed. Modifications using suction cups, also found on some 3rd party sticks, were generally regarded as more trouble than they were worth.

The CX40 was infamous for its eventual breakdown from one of two problems. One was that the control ring on the bottom of the stick moulding was not very robust, and either the ring itself or the four small tabs that connected it to the stick could be broken by applying too much force. The ring transmitted the force from the stick to the switches, so if it broke, the stick would no longer operate properly in that direction. This happened with "distressing regularity". The other problem was that the switches themselves would eventually wear out due to repeated use, normally with the top membrane cracking or the tape holding it in place wearing off.

A common modification was to replace the switches with miniature snap-action switches (microswitches). Some of these, however, have the problem that their actuation is non-linear; they require considerable force to start moving compared to the force needed to complete the motion. When used in an otherwise unmodified CX40, this caused it to be more difficult to move along the diagonals, as one of the two switches being pushed would normally reach the threshold first, causing motion in that direction while the other was not yet pressed. In games that required fine control, like Jumpman, these solutions were generally unsuitable. Newer switches improve this action.

Versions

CX10

The original CX10 version was designed by Steve Bristow for the 2600 and produced only for a single year. Many of these had the word "ATARI" printed in white letters on a thin metal plate at the very top of the stick.

Internally, the CX10 differed from the CX40 primarily in the switch mechanisms. In the CX10, a thin plastic plate was placed directly on top of the PCB, separated by a few millimetres. Cup-shaped protrusions on the top surface held a small metal spring, and opposite these on the bottom surface of the plate was a small metal bar. The plate was positioned so the bars on the bottom of the cups were positioned over similar bars on the PCB, although aligned perpendicularly. Slits cut into the plate on either side of the cup made that section of the plate flexible. When the stick was moved, it pressed on the spring, eventually providing enough force to bend that section of the plate down until the two metal bars made contact. The springs provided the recentering force. This operation required more physical motion to depress the switches than on the CX40, and the CX10 is generally considered to be less suitable for gaming.

CX40

The CX40 was designed by James Asher to replace the CX10, with the aim of greatly improving its ability to be inexpensively mass-produced. By 1983, one out of every five American homes had one. This model accounts for the vast majority of Atari's production run.

The CX40 is nearly identical to the CX10 externally, but lacks the printing on the top of the stick, and replaced the uppermost wedge in the ring of embossing with the word "TOP". By 1986 the CX40 was difficult to obtain, and some dealers could only order it with software.

A new CX40 using gray colored plastic for the base was released with the Atari XEGS computer. It also dispensed with the orange paint on the embossing on the base. It was otherwise identical to the earlier CX40, retaining the black plastic cover on the stick and the red fire button.

Other joysticks from Atari

The CX40 remained popular throughout the run of the 2600 and Atari 8-bit computers, but by the end of their run many 3rd party improvements had appeared and Atari introduced new controllers of their own.

Released in the summer of 1983, the CX842 "Remote Control Wireless Joystick" was a rebranded version of the Cynex Game Mate 2. These were essentially CX40's on top of a radio device, so the bases were quite large as a result. A separate receiver box completes the connection to the console.

Atari also advertised the CX43 "Space Age Joystick", the most radical change to the basic concept. This was essentially a very small version of the CX40 mounted on top of a trigger-style handle with a fire button on the front. The handle was intended to be held in one hand while the other operated the very short stick on top. The CX43 may be a rebranded version of the Milton Bradley HD2000, which was never released.

The Atari 7800's CX-24 Pro-Line joystick was designed to be backward compatible with the 2600 and its games. The Pro-Line was originally advertised specifically for the 2600 in 1983, but was not released until it was made the pack-in controller for the 7800. Its right fire button was designed to switch between functioning as a discrete button for 7800 games, and as a duplicate of the left fire button (which was functionally identical to the CX-40's lone fire button) for 2600 games. The Atari CX-78 Joypad, available in PAL markets in place of the CX-24, had the same compatibility as the Pro-Line stick.

3rd party alternatives

The CX40 was the only model in widespread use until about 1981, when the introduction of Space Invaders on the 2600 quadrupled that platform's sales. This led to a thriving 3rd party market for better sticks for use on the 2600.

Many were almost identical copies of the CX40. Other examples of barely-modified sticks include the Gemini GemStick, which was essentially a CX40 with a somewhat larger base and the fire button replaced by a larger yellow version. The Gemstick 2 added a second button in the upper right. The Suncom Slik-Stik was slightly more modified with the case rounded off and a large red plastic ball at the tip of a shortened stick. The shorter stick made it more suitable for single-handed use. Suncom later introduced the TAC-2, essentially a larger Slik-Stik with buttons on both sides, for left-handed users.

For the VIC-20, Commodore International introduced a joystick that was essentially identical to the Atari model with the exception that the top plate on the base was white instead of black. This prompted Atari to sue for patent violations. Commodore responded by introducing the 1311, a modified version that made the case more rectangular, changed the stick from a cylinder to a triangle, and replaced the single round fire button with a larger one running across the top of the stick, making it suitable for use in either hand. These changes also rendered it painful to use and it was widely panned.

The Wico Command Control was one of the earliest examples of a stick that differed radically from the Atari pattern in mechanical terms. Wico was a major supplier of arcade game joysticks and adapted these mechanisms for home use. These replaced the membrane switches with leaf switches that were much more robust and provided the recentering force internally. A large rounded-corner square block of plastic provided the moving surface similar to the hemisphere in the CX40, but was shaped to provide more obvious directions when pressed, sliding along the edges of the square. The stick, a steel tube covered in a bat-like red plastic moulding, featured a button on top that pressed a shaft running through the center of the stick to another switch below the main assembly.

The base was greatly enlarged with the specific intent of making it useful in one-handed play, which operated in concert with the stick-top button. A switch on the base selected whether the button on the handle or the base was active. The case also featured moulded indents in the bottom that made it easier to hold in two-hand use. The result was a system that was significantly more robust than the Atari sticks, but also much more complex and expensive. Later versions added a switch for "autofire" that caused the fire button to be repeatedly pressed while held down, and even later the bat-like handle was replaced by a ball like those found on arcade sticks. A flightstick-style handle with finger grooves was also offered. It was consistently rated very highly.

The Epyx 500XJ was among a very few designs that broke from the Atari mould completely. Like the Competition Pro, the 500XJ's mechanism was based around a steel shaft pressing on microswitches and offered a similar feel. Unlike the Command Control, the 500XJ's shaft pressed directly on the switches, making it harder to press into the diagonals. More importantly, the base of the unit was completely changed, consisting of a moulded form that was designed to be easily gripped by the left hand with the index finger naturally positioned over a fire button located on the bottom right side of the case. Both robust and unique, the 500XJ garnered widespread praise and was the only other joystick of the era to achieve widespread popularity to the point of becoming a standard of sorts.

Early gamepads were essentially CX40s with the base exposed to the user and the joystick on top removed. Sega's Master System and Genesis/Mega Drive controllers are compatible with the 2600, although the console can only read one fire button on the Sega controllers – the 2 button on Master System controllers, and the B button on Genesis controllers. The Sega Control Stick was the only Sega-made controller actually marketed for its compatibility with Atari and Commodore systems. Due to the unique setup of the 7800's fire buttons, Sega controllers are not compatible with 7800 games that require two fire buttons, although they can be used with 7800 games that only use one fire button.

Atari joysticks on other platforms

The Atari joystick was so popular that adaptors for its standard of connector were available for platforms like the Apple II and IBM PC. There were even factory modified CX40s, notably the Trisstick from Big Five Software, that placed the converter electronics inside the CX40 case and replaced the cable with one suitable for the TRS-80.

While its single-button configuration makes it unsuitable for general use with Sega's consoles, an Atari joystick can be used in the player two port for certain two-player games with minimal controls, so long as a standard Sega controller is plugged into the player one port. For example, a CX-40 can be used to control Tails in two-player mode in Sonic the Hedgehog 2, as all three Genesis fire buttons are mapped to the same jump/spin-dash function (and with the Master System for the 1 and 2 buttons), although player two cannot pause the game due to the absence of a Start button.

Notes

- CX40s were widely available for under $10.

- Perhaps all of them, sources are not specific

- Apparently a re-branded Konix Speedking

References

Citations

- ^ Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 323.

- Wolf, Mark (2012). Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Wayne State University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0814337226.

- Lidwell, William; Manacsa, Gerry (2011). Deconstructing Product Design. Lockport Publishers. p. 97. ISBN 9781592537396.

- Rollings, Andrew; Adams, Ernest (2003). Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams on Game Design. New Riders. p. 167. ISBN 9781592730018.

- Lidwell, William; Manacsa, Gerry (2011). Deconstructing Product Design. Rockport Publishers. p. 98. ISBN 9781592537396.

- ^ Plotkin 1982.

- "advertisements". Modern Photography: 141. 1982.

- "Catalog - Atari (CO21776-Rev. A)". AtariAge.

- Sivakumaran, Soori (1986). Electronic Computer Projects. COMPUTE! Publications. p. 23. ISBN 0-87455-052-1. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- Ahl, David (Fall 1983). "Game Controllers And Accessories". Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games. p. 115.

- ^ CX40.

- Grand & Yarusso 2004, pp. 337–342.

- ^ Plotkin 1988.

- "Autofire Circuit".

- Alaimo, Chris (1 April 2010). "Replacing the PCB in your Atari CX-10 "Heavy Sixer" joystick". Classic Gaming Quarterly.

- Grand & Yarusso 2004, pp. 342–349.

- "A CX-40 Micro Switch Upgrade". AtariAge. 2 July 2015.

- ^ CX10.

- Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 235.

- ^ Ahl, David H.; Rost, Randi J. (1983), "Blisters And Frustration: Joysticks, Paddles, Buttons and Game Port Extenders for Apple, Atari and VIC", Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games, 1 (1): 106ff

- Bisson, Gigi (May 1986). "Antic Then & Now". Antic. pp. 16–23. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "The Atari 2600 Remote Controlled Joystick". Atari Museum. Archived from the original on 2003-06-23.

- "Atari Space Age Joystick". AtariAge.

- "Catalog - Atari (CO21776-Rev. A)". AtariAge.

- Kent, Steven (2001). Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ Hybner 1986.

- Goldberg & Vendel 2012, p. 597.

- "Atari wins joystick battle". InfoWorld: 5. 29 November 1982.

- "Worst Retro Joystick Ever?". Retro Thing. 28 December 2011.

- "1311 Joystick". Commodore Retro Heaven.

- "Inside the WICO Command Control Joystick". AtariAge.com. 26 June 2015.

- Pearlman, Gregg (January 1987). "500XJ Joystick". Antic.

- "Control Stick". Sega Retro. March 13, 2020.

- Woita, Steve (2007), Classic Gaming Expo – Steve Woita, retrieved 2007-03-26

- "Company". Big Five Software.

Bibliography

- US expired 4124787, Gerald R. Aamoth & John K. Hayashi, "Joystick controller mechanism operating one or plural switches sequentially or simultaneously", published 1978-11-07, issued 1978-11-07, assigned to Atari Inc

- US expired 4349708, James C. Asher, "Joystick control", published 1982-09-14, issued 1982-09-14, assigned to Atari Inc

- Goldberg, Marty; Vendel, Curt (2012). Atari Inc: Business is Fun. Syzygy Press. ISBN 9780985597405.

- Grand, Joe; Yarusso, Albert (2004). Game Console Hacking. Syngress.

- Hybner, Tomas (October 1986). "Tovl joystickar testade!". Datormagazin: 18.

- Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2014). Stella and Combat: A BIT of Racing the Beam. MIT Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780262316446.

- Plotkin, Dave (December 1982). "Joystick Survey: Alternatives to the Atari controller". ANTIC.

- Plotkin, Dave (December 1988). "The Joy of Joysticks". ANTIC.

External links

- List of Atari-compatible joysticks at the Wayback Machine (archived November 30, 2016)