The Atchafalaya Basin, or Atchafalaya Swamp (/əˌtʃæfəˈlaɪə/; Louisiana French: Atchafalaya, [atʃafalaˈja]), is the largest wetland and swamp in the United States. Located in south central Louisiana, it is a combination of wetlands and river delta area where the Atchafalaya River and the Gulf of Mexico converge. The river stretches from near Simmesport in the north through parts of eight parishes to the Morgan City southern area.

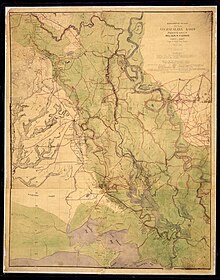

The Atchafalaya is different among Louisiana basins because it has a growing delta system (see illustration) with wetlands that are almost stable. The basin contains about 70% forest habitat and about 30% marsh and open water. It contains the largest contiguous block of forested wetlands remaining (about 35%) in the lower Mississippi River valley and the largest block of floodplain forest in the United States. Best known for its iconic cypress–tupelo swamps, at 260,000 acres (110,000 ha), this block of forest represents the largest remaining contiguous tract of coastal cypress in the United States.

Geographical features

The Atchafalaya Basin and the surrounding plain of the Atchafalaya River is filled with bayous, bald cypress swamps, and marshes, which give way to brackish estuarine conditions, and end in the Spartina grass marshes where the Atchafalaya River meets the Gulf of Mexico. It includes the Lower Atchafalaya River, Wax Lake Outlet, Atchafalaya Bay, and the Atchafalaya River and bayous Chêne, Boeuf, and Black navigation channel. See maps and photo views of the Atchafalaya Deltas centered on 29°26′30″N 91°25′00″W / 29.44167°N 91.41667°W / 29.44167; -91.41667.

The basin, which is susceptible to long periods of deep flooding, is sparsely inhabited. The Basin is about 20 miles (32 km) in width from east to west and 150 miles (240 km) in length. The Basin is the largest existing wetland in the United States with an area of 1,400,000 acres (5,700 km), including the surrounding swamps outside of the levees that historically were connected to the Basin. The Basin contains nationally significant expanses of bottomland hardwoods, swamplands, bayous, and back-water lakes. The Basin's thousands of acres of forest and farmland are home to the Louisiana black bear (Ursus americanus luteolus), which has been on the United States Fish and Wildlife Service threatened list since 1992.

The few roads that cross the Basin follow the tops of levees. Interstate 10 crosses the basin on elevated pillars on a continuous 18.2-mile (29.3 km) bridge from Grosse Tete, Louisiana, to Henderson, Louisiana, near the Whiskey River Pilot Channel at 30°21′50″N 91°38′00″W / 30.36389°N 91.63333°W / 30.36389; -91.63333.

The Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1984 to improve plant communities for endangered and declining species of wildlife, waterfowl, migratory birds and alligators.

Basin geology and flooding

The Atchafalaya Basin has a long relationship with the Mississippi River throughout the Holocene epoch, and the geology of the modern basin is a direct manifestation of that relationship. The Atchafalaya Basin has been part of three historic depositional lobes (Sale-Cypremort, Teche, and Lafourche lobes) of the Mississippi River Delta Plain that formed south Louisiana, and active delta lobe development is currently occurring at the mouth of the Atchafalaya River and Wax Lake Outlet. The geology of the current basin has been driven by flows of Atchafalaya River water and sediment that flowed into open water areas through relict Mississippi River distributary channels.

The Atchafalaya Basin contains lacustrine and coastal delta landscapes. Natural filling of the basin with sediment was accentuated with the building of the flood control levees that were completed in the 1940s. After the levees, sediment was directed into an area about one-third the size of the original basin. An example of the lacustrine delta development can be seen at Lake Fausse Pointe State Park, where levees severed the connection between the Grand Bayou distributary and the lake, and delta development was frozen in time.

Geologically, the Atchafalaya River has been a backswamp, low area between the paths of the Mississippi River through the process of delta switching, which has built the extensive delta plain of Louisiana. The natural levees of the Mississippi River (on the east) and the levees along its previous course (now Bayou Teche) on the west define the Atchafalaya Basin. The central basin is further bordered by man-made levees designed to contain and funnel floodwaters released from the Mississippi at the Old River Control Structure and the Morganza Spillway south toward Morgan City and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico. Historically there were small and few channel connections to the Mississippi River. The historic lack of significant channel connection indicates that the Atchafalaya River Basin did not receive significant sediment from the Mississippi except during large floods.

During the mid-19th century, manmade channel alterations, including the removal of a large log jam and dredging, permanently connected the Atchafalaya River to the Mississippi River. From then until the completion of the Old River Control Structure in 1963, the Mississippi was increasingly diverting flow into the shorter and steeper path of the Atchafalaya channel. By law, a regulated 30 percent of the latitudinal flow water from the Mississippi, Red and Black rivers is diverted into the Atchafalaya at the Old River Control Structure. This flow diverts on average 25 percent of the Mississippi River flow down the Atchafalaya.

In times of extreme flooding, the US Army Corps of Engineers may open the Morganza Spillway and other spillways to relieve pressure on levees and control structures along the Mississippi. On May 13, 2011, in the face of a rising Mississippi River that threatened to flood New Orleans and other heavily populated parts of Louisiana, the USACE ordered the Morganza Spillway opened for the first time since 1973. This water floods the Atchafalaya Basin between the levees along the western and eastern limits of the Morganza and Atchafalaya basin floodways.

Further information: Atchafalaya RiverDegradation of the swamps

The control of the river's floods, along with those of the Mississippi River, has become a controversial issue in recent decades. The US Geological Survey (USGS) reports that Mississippi River delta salt marshes are wetlands degrading at a rate of 29 square miles per year (2.4 km/Ms). The Atchafalaya River Deltas are the only locations of land growth along the Louisiana Gulf Coast.

During the early 20th century, the Atchafalaya River Basin was designated as a spillway for floods of the Mississippi River. In order to facilitate this emergency plan without flooding adjacent agriculture and towns, protective levees were built dividing the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway from large portions of the historic swamp boundaries. A central channel was dredged through some existing channels and in some places through swamp forest. At that point the isolated Atchafalaya River Basin was permanently connected to a very large, sediment-rich river.

From 1850 to 1950 open water decreased from 190 to 110 square miles (490 to 290 km). From 1950 to 2005 the amount of open water decreased to 73 square miles (190 km). When the Atchafalaya Basin flow plan was implemented (1950–1974), 30 percent of the total Atchafalaya River flow was designated to be directed off the main channel, 15 percent to the east and 15 percent to the west side. As a result of the Atchafalaya River channel bed incision, in the early 21st century the flow distribution is 13 percent of the total flow, with a flow distribution of 7 percent to the east side and 6 percent to the west side as reported by the USGS. This decrease in flow across the floodplain, in conjunction with high organic deposition from trees and floating vegetation and high water temperature, has resulted in large areas of low-dissolved oxygen water. Where once the water was black (1850), the water became brown (1927). Where the water was formerly brown (1927), it is now black (2009).

During the period of 1960–1980, oil and gas exploration and development in Louisiana increased dramatically. Numerous large access canals and pipeline canals were dredged through deep swamp areas, across bayous, and across the Atchafalaya River. In some areas of the Basin, there are 1.2 miles (2 km) or more of access canals to every 0.62 miles (1 km) of natural bayou. These large channels (100–165 feet or 30–50 metres wide by 5–10 feet or 2–3 metres deep) have fundamentally changed the hydrology of the swamps. Deep swamp areas that were hydraulically isolated from sediment were connected directly to the river and its sediment and suffered rapid filling. The USGS has measured sediment deposition rates of up to 10 inches (30 cm) per year where these channels enter open water, and 1.6 inches (4 cm) per year on adjacent floodplains. In some places natural bayous have filled in due to flow capture by access canals.

Spoil material from the canals was deposited adjacent to the canals, further impeding the natural flow across the floodplain.

The Bayou Chene Community

From 1830 to 1953, the community of Bayou Chene thrived as a center for logging, hunting, trapping, and fishing in the heart of the Atchafalaya Basin. Now buried underneath at least twelve feet of silt, Bayou Chene is one of several abandoned communities in the midst of the basin.

The earliest settlers of the Bayou Chene region were the native Chitimacha tribe. Several villages important to the Chitimacha were located around Bayou Chene including the Village of Bones or Namu Katsi and the Cottonwood Village, known as Kushuh Namu in the Chitimacha language. One of the earliest written accounts of the Bayou Chene region comes from French explorer C.C. Robin who, while paddling through the Basin in 1803, wrote:

After long sinuosities which form innumerable islands, among which the inexperienced traveler would require the thread of Ariadne in order not to wander forever, the river opens suddenly into a magnificent lake of several leagues extent. The sudden light surprises the traveler and the beauty of the water, set about with tall trees, forms an enchanting sight.

By 1841, between fifteen and twenty families were farming along the banks of "Oak Bayou" or Bayou Chene. The population rose quickly over the next twenty years, as the United States Census of 1860 counted 675 residents in the community. By the 1870s, a majority of those living along Bayou Chene were involved in logging bald cypress, tupelo, and other bottomland hardwoods in the basin.

By the early twentieth century, Bayou Chene was the center of the Atchafalya Basin's cypress and fur industry and housed many of the 1,000 full-time fisherman who fished the swamp's shallow bottoms. Writing about her family's experiences in the region, Gwen Roland describes how the community relied upon the basin's waters for everything, including transportation:

Out here on the Chene, our skiffs flare out on the sides so they float high like an acorn cap; it makes them quick to steer with an extra push on one oar or the other. This skiff floated deep and straight like a water trough or a coffin.

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 nearly demolished the community. Rising seven feet above natural levees, the floodwaters inundated Bayou Chene for weeks. Local folklore says a village goat survived in the Methodist Church during this period on hymnals and wallpaper.

The Great Depression hit the residents of Bayou Chene hard, but many former residents look fondly on the massive flood control projects promulgated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that provided gainful employment during the period. As a result of the 1927 flood, the entire Atchafalaya Basin was designated an official floodway and a series of man-made levees were built that would permanently alter flooding patterns in the region. Further flooding in 1937 encouraged many residents to move their homes to higher ground, but even these measures were not enough to protect the community from annual flooding. After years of rising waters, the community came to an end with the closing of the United States Post Office at Bayou Chene in 1952. Most of Bayou Chene's former residents relocated to the fringes of the basin in towns like New Iberia, St. Martinville, and Breaux Bridge. Today, little remains of the swamp community buried underneath the murky waters of the Atchafalaya.

Gallery

-

Aerial view of the Big Island Mining Project restoration site on Atchafalaya Bay

Aerial view of the Big Island Mining Project restoration site on Atchafalaya Bay

-

View of the south side of the I-10 bridge crossing the basin

View of the south side of the I-10 bridge crossing the basin

See also

- Mississippi River Delta

- Wetlands of Louisiana

- List of Louisiana rivers

- Atchafalaya National Heritage Area

References

- "Coastal Louisiana Basins". lacoast.gov. Archived from the original on Dec 9, 2023. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ Piazza, Bryan P (25 February 2014). The Atchafalaya River Basin: History and Ecology of an American Wetland. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-62349-039-3.

- "Atchafalaya". 1998-12-05. Archived from the original on 1998-12-05. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- Hupp, Cliff R.; Demas, Charles R.; Kroes, Daniel E.; Day, Richard H.; Doyle, Thomas W. (2008). "Recent Sedimentation Patterns Within The Central Atchafalaya Basin, Louisiana" (PDF). Wetlands. 28 (1): 125–140. doi:10.1672/06-132.1. S2CID 4492803. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-09. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- Audubon Wetlands Campaign Archived April 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Leslie Williams (June 20, 1998). "The Bear Facts Scientists Hot On Trail Of Species". National. The Times-Picayune. p. A1.

- "Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". www.fws.gov. Archived from the original on Dec 10, 2023. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- Map Produced By Gmap4 | Enhanced Google Map Viewer

- "USGS Fact Sheet: Louisiana Coastal Wetlands". 1997-10-12. Archived from the original on 1997-10-12. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ Hale, L., Waldon, M.G., Bryan, C.F., Richards, P.A. (1999). "Historic patterns of Sedimentation in Grand Lake, Louisiana." Proceedings, Recent Research in Coastal Louisiana Natural System Function and Response to Human Influence. Roza, L.P., Nyman, J.A., Proffitt, C.E., Rabalais, N.N., Reed, D.J., and Turner, R.E. (eds). Louisiana Sea Grant, Baton Rouge, La.

- Eos magazine, March 2009, Moeras van de verdwenen reuzen

- ^ Maygarden, Benjamin (1999). "Bayou Chene: The Life Story of an Atchafalaya Basin Community". Preserving Louisiana's History. 2: 2–31.

- Robin, C.C. (1966). Voyage to the Interior of Louisiana (Translated by Stuart O. Landry, Jr. ed.). New Orleans: Pelican Publishing Company.

- ^ Nickens, T. Edward (November 2003). "Saving Atchafalaya". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ Roland, Gwen (2015). Postmark Bayou Chene (First ed.). Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-6144-9.

- Randolph, Ned (9 Feb 2018). "River Activism: "Levees Only" and the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927". Media and Communication. 6 (1): 43–51. doi:10.17645/mac.v6i1.1179. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

External links

- Atchafalaya Basin Program

- The Atchafalaya Heritage Area

- National Weather Service: Atchafalaya Basin

- Satellite view of the Atchafalaya delta on Google maps

- Voices of the Atchafalaya—Documentary featuring pictures and oral histories from the basin.

- Lockwood, C.C. C.C.Lockwood's Atchafalaya. Louisiana State University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-8071-3259-3.

| Wetlands | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types and landforms | |||||

| Life | |||||

| Soil mechanics | |||||

| Processes | |||||

| Classifications | |||||

| Conservation |

| ||||

| Related articles | |||||

- Wetlands and bayous of Louisiana

- Gulf of Mexico

- Mississippi River

- Intracoastal Waterway

- Acadiana

- Landforms of Assumption Parish, Louisiana

- Landforms of Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana

- Landforms of Iberia Parish, Louisiana

- Landforms of Iberville Parish, Louisiana

- Landforms of Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana

- Landforms of St. Landry Parish, Louisiana

- Landforms of St. Martin Parish, Louisiana

- Landforms of St. Mary Parish, Louisiana

- Estuaries of Louisiana

- Atchafalaya River