Atmospheric temperature is a measure of temperature at different levels of the Earth's atmosphere. It is governed by many factors, including incoming solar radiation, humidity, and altitude. The abbreviation MAAT is often used for Mean Annual Air Temperature of a geographical location.

Near-surface air temperature

"Surface air temperature" redirects here. Not to be confused with Soil temperature or Sea surface temperature. For temperature measurements made by instruments, see Instrumental temperature record. For temperature changes relevant to historical climate change over Earth's geologic past (distinguished from recent climate change), see Temperature record.The temperature of the air near the surface of the Earth is measured at meteorological observatories and weather stations, usually using thermometers placed in a shelter such as a Stevenson screen—a standardized, well-ventilated, white-painted instrument shelter. The thermometers should be positioned 1.25–2 m above the ground. Details of this setup are defined by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

A true daily mean could be obtained from a continuously recording thermograph. Commonly, it is approximated by the mean of discrete readings (e.g. 24 hourly readings, four 6-hourly readings, etc.) or by the mean of the daily minimum and maximum readings (though the latter can result in mean temperatures up to 1 °C cooler or warmer than the true mean, depending on the time of observation).

The world's average surface air temperature is about 14 °C.

Temperature versus altitude

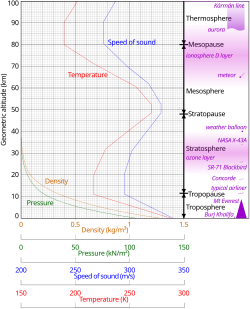

Temperature varies greatly at different heights relative to the surface of the Earth; it is this variation which characterizes the four layers that exist in the atmosphere. These layers are the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere.

The troposphere is the lowest of the four layers and extends from the surface of the Earth to about 11 km (6.8 mi) into the atmosphere, where the tropopause (the boundary between the troposphere stratosphere) is located. The width of the troposphere can vary depending on latitude: for example, the troposphere is thicker in the tropics (about 16 km (9.9 mi)) because the tropics are generally warmer, and thinner at the poles (about 8 km (5.0 mi)) because the poles are colder. Temperatures in the atmosphere decrease with height at an average rate of 6.5 °C (11.7 °F) per kilometer. Because the troposphere experiences its warmest temperatures closer to Earth's surface, there is great vertical movement of heat and water vapour, causing turbulence. This turbulence, in conjunction with the presence of water vapour, is the reason that weather occurs within the troposphere.

Following the tropopause is the stratosphere. This layer extends from the tropopause to the stratopause, which is located at an altitude of about 50 km (31 mi). Temperatures remain constant with height from the tropopause to an altitude of 20 km (12 mi), after which they start to increase with height. This is referred to as an inversion, and it is because of this inversion that the stratosphere is not turbulent. The stratosphere receives its warmth from the sun and the ozone layer which absorbs ultraviolet radiation.

The next layer, the mesosphere, extends from the stratopause to the mesopause (located at an altitude of 85 km (53 mi)). Temperatures in the mesosphere decrease with altitude, and are the coldest in the Earth's atmosphere. This decrease in temperature can be attributed to the diminishing radiation received from the Sun, after most of it has already been absorbed by the thermosphere.

The fourth layer of the atmosphere is known as the thermosphere, and extends from the mesopause to the 'top' of the collisional atmosphere. Some of the warmest temperatures can be found here, due to its reception of strong ionizing radiation at the level of the Van Allen radiation belt.

Temperature range

The variation in temperature that occurs from the highs of the day to the cool of nights is called diurnal temperature variation. Temperature ranges can also be based on periods of a month or a year.

The size of ground-level atmospheric temperature ranges depends on several factors, such as:

- Average air temperature

- Average humidity

- The regime of winds (intensity, duration, variation, temperature, etc.)

- Proximity to large bodies of water, such as the sea

The figure on the left shows an example of monthly temperatures recorded in the city of Campinas, Brazil, which lies approximately 60 km north of the Tropic of Capricorn at 22 degrees latitude. Average yearly temperature is 22.4 °C, ranging from an average minimum of 12.2 °C to a maximum of 29.9 °C. The average temperature range is 11.4 °C. Variability throughout the year is small (standard deviation of 2.31 °C for the maximum monthly average and 4.11 °C for the minimum). The graph also shows the typical phenomenon of increased temperature ranges during winter.

In Campinas, for example, the daily temperature range in July (the coolest month of the year) may typically vary between 10 and 24 °C (range of 14 °C), while in January, it may range between 20 and 30 °C (range of 10 °C).

The effect of latitude, tropical climate, constant gentle wind, and seaside locations show smaller average temperature ranges, smaller variations of temperature, and a higher average temperature (the graph on the right, taken for the same period as Campinas, at Aracaju, also in Brazil and located at a latitude of 10 degrees, nearer to the Equator). Average maximum yearly temperature is 28.7 °C and average minimum is 21.9 °C. The average temperature range is 5.7 °C only. Temperature variation throughout the year in Aracaju is very damped, with a standard deviation of 1.93 °C for the maximum temperature and 2.72 °C for the minimum temperature.

Lifted minimum temperature

See also: Surface temperature inversionThe minimum temperature on calm, clear nights has been observed to occur not on the ground, but rather a few tens of centimeters above the ground. The lowest temperature layer is called Ramdas layer after Lakshminarayanapuram Ananthakrishnan Ramdas, who first reported this phenomenon in 1932 based on observations at different screen heights at six meteorological centers across India. The phenomenon is attributed to the interaction of thermal radiation effects on atmospheric aerosols and convection transfer close to the ground.

Global temperature

See also: Global surface temperature, Instrumental temperature record, Global temperature record, and Schumann resonances § Global temperatureThe concept of a global temperature is commonly used in climatology, and denotes the average temperature of the Earth based on surface, near-surface or tropospheric measurements. These temperature records and measurements are typically acquired using the satellite or ground instrumental temperature measurements, then compiled using a database or computer model. Long-term global temperatures in paleoclimate are discerned using proxy data.

See also

- Apparent temperature

- Atmospheric thermodynamics

- Brightness temperature

- Emissivity of Earth's atmosphere

- Equivalent temperature

- Freezing air temperature

- Instrumental temperature record

- Lapse rate

- Outside air temperature, in aviation

- Room temperature

- Total air temperature, in aviation

References

- Geometric altitude vs. temperature, pressure, density, and the speed of sound derived from the 1962 U.S. Standard Atmosphere.

- Baker, Donald G. (June 1975). "Effect of Observation Time on Mean Temperature Estimation". Journal of Applied Meteorology. 14 (4): 471–476. Bibcode:1975JApMe..14..471B. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1975)014<0471:EOOTOM>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Ross, Sheila Loudon (11 March 2013). Weather and climate: an introduction. Don Mills, Ontario, Canada. ISBN 978-0-19-544587-9. OCLC 812064583.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thompson, Russell D. (1998). Atmospheric Processes and Systems. Routledge.

- "Earth's Atmosphere: A Multi-layered Cake". NASA. Archived from the original on 2019-10-06.

- ^ "Station statistics". Agritempo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- Ramdas, L.A. and Atmanathan, S., 1932. The vertical distribution of air temperature near the ground at night. Beitrage zur Geophysik, v.37, pp. 116–117.

- Lake, JV (1955). "The nocturnal heat balance". Nature. 176 (4470): 32–33. Bibcode:1955Natur.176...32L. doi:10.1038/176032b0. S2CID 4210305.

- Hansen, James E. "GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP)". National Aeronautic and Space Administration. Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Retrieved 1 September 2011.