Office in Wellington, New Zealand

| Aon Centre | |

|---|---|

Aon Centre at 1 Willis Street Aon Centre at 1 Willis Street | |

| Former names | BNZ Centre, State Insurance building |

| General information | |

| Type | Office |

| Architectural style | Structural Expressionism |

| Location | 1 Willis Street, Wellington, New Zealand |

| Coordinates | 41°17′12″S 174°46′35″E / 41.286741°S 174.776393°E / -41.286741; 174.776393 |

| Construction started | 1973 |

| Completed | 1984 |

| Owner | Precinct Properties New Zealand Ltd (formerly the AMP NZ Office Trust) |

| Height | 103 m (338 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Steel moment frame |

| Floor count | 30 (3 below ground, 27 above) |

| Floor area | 26,892 m (net lettable) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Stephenson & Turner Architects |

| Structural engineer | Brickell, Moss, Rankine & Hill |

The Aon Centre is a commercial office building at 1 Willis Street in Wellington, New Zealand, formerly named the BNZ Centre then the State Insurance Building. When completed in 1984, it was the tallest building in New Zealand, overtaking the 87m Quay Tower in Auckland. It is notable for its strong, square, black form, in late International Style modernism, and for a trade dispute which delayed the construction by a decade. It remained the tallest building in New Zealand until 1986, when the 106 meter BNZ Tower opened in Auckland, and is currently the second tallest building in Wellington after the Majestic Centre.

History

The building was designed by Stephenson & Turner Architects in the late 1960s. BNZ (Bank of New Zealand) began purchasing land for the building in 1969. Approval to build was granted by the Town Planning Committee on 14 June 1972, after the building codes were rewritten to allow the development "out of common interest". Construction began in 1973, but was delayed in part by a labour demarcation dispute with the boilermakers trade union, who claimed the exclusive right of its members to weld the structural steel. The dispute was characteristic of the time, disrupted construction for six years and discouraged construction of steel buildings across the country. In response to the problem, the government of the day deregistered the Wellington Boilermakers Union. The dispute would lead the building to be four times over budget, ultimately costing $93 million.

In 1979, the original building contract was terminated and a new contract to finish the building was signed in 1981. The complex was completed and occupied in late 1984.

After the BNZ moved its head office to Auckland in 1998, State Insurance purchased the naming rights to the building, renaming it the State Insurance Tower. In 2002, BNZ sold the building to Willis Developments, a German investment group. By 2013 the building had been sold to Precinct Properties. In 2018, insurance brokerage Aon purchased the naming rights to the building, naming it the Aon Centre. Aon have been tenants in the building since 2013.

Design

The building draws inspiration from Mies Van de Rohe’s tower buildings (Lakeshore Drive apartment buildings in Chicago and Seagram Tower in New York) and Yuncken Freeman's BHP House in Melbourne. Members of the BNZ development team travelled with Stephenson & Turner Architects to view architecture in the USA, Europe and Australia. The building has a square footprint and all sides rise vertically without variation. The building's imposing design has been criticised, with architect Sir Ian Athfield calling it "Darth Vader's pencil box".

Standing at 103 metres, with 27 floors above ground and three basement levels, it was New Zealand’s tallest building from 1984 to 1986, until eclipsed by buildings such as Auckland's BNZ Centre. It was Wellington's tallest building until 1991, when the Majestic Centre was built on the same street.

Because of its sheer size and steel construction the building is relatively flexible. Its response to earthquakes is relatively good. Of greater effect is Wellington’s wind which is accommodated by the building’s ability to flex by up to 300 mm in hurricane-force winds, a feature which has caused motion sickness in workers in the building. The seismic and wind-resisting frames of the building consist of a steel “tube” built around the perimeter of the tower connected via floor diaphragms to the stiffer central core. The floors are steel decks with concrete topping. The façade consists of precast concrete units faced with black Brazilian tijuca granite, with black-glazed windows built into them. The window units are designed to cope with 38mm of inter-storey drift, which is defined as "the difference in lateral deflection between two adjacent stories of a building subjected to lateral loads". Window panes have shattered and fallen from the building on several occasions.

Underneath the building was a shopping centre and food court. There were also underground passages that passed under Willis Street to the nearby Old Bank and Grand Arcades, but these have since been blocked up. The food court area was remodelled and reopened in 2023 as a new entertainment venue called Willis Lane, which includes a mini-golf course, bowling alley and various bars and eating places.

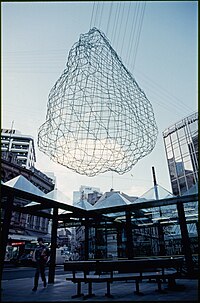

Above ground the tower is accessed by a two-storey-high glazed lobby. The BNZ originally occupied 10 floors: three levels were used for the branch office, and the top seven floors were occupied by their head office. In 2002, an open, windy plaza area at the base of the building was covered in to provide additional retail spaces. The Rock, a sculpture by Neil Dawson, was originally suspended above the open area at the front of the building, but after the open area was closed in the sculpture was relocated to the Willeston Street frontage.

See also

References

- ^ Hunt, Tom; Thomson, Rebecca (31 December 2014). "Window falls out from high rise". Stuff. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Huggins, John (1986). "BNZ Building: Wellington as symbol and architecture". Architecture New Zealand (5): 11.

- ^ Stephenson and Turner (1986). "BNZ Wellington". Architecture New Zealand (5): 25.

- ^ "A monument to militancy". Stuff. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- "Wellington union deregistered". The Press. 4 September 1976 – via Papers Past.

- "Protest stoppage by Seamen's Union". The Press. 27 October 1976 – via Papers Past.

- Mulrooney, Paul (8 August 2002). "Germans buy BNZ Centre". Dominion Post. ProQuest 337963088.

- Gibson, Anne (21 February 2013). "Precinct Properties boosts half-year profit". The New Zealand Herald. ProQuest 1289031663.

- "Ex-BNZ & State Tower takes on third name – The Bob Dey Property Report". Ex-BNZ & State Tower takes on third name. Bob Dey Property Report. 28 March 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Balasoglou, John, ed. (February 2006). Stephenson & Turner. Auckland, New Zealand: Balasoglou Books. pp. 81–82. ISBN 9780958262552.

- "Wellington | Statistics | EMPORIS". Emporis. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Works Corporation to help stop building sway". The Press. 13 April 1988 – via Papers Past.

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology (February 1995). Literature Review on Seismic Performance of Building Cladding Systems [Report] (PDF). USA: US Department of Commerce. p. 43.

- Kernohan, David (1989). Wellington's new buildings. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University Press. ISBN 0864730853.

- Uma, S. R.; KIng, A. B.; Holden, T. (2012). Inter-storey Drift Limits for Buildings at Ultimate limit States (PDF). New Zealand: 2012 NZSEE Conference.

- Hunt, Tom (28 February 2017). "Wellington high-rise tenants warned of spontaneously breaking windows". Stuff. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- "BNZ Centre, Wellington". tiaki.natlib.govt.nz. 1984–1986. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Building banks in Wellington". BNZ Heritage.

- Heard, Stephen (6 August 2023). "Spotlight on: An upscale food court and underground arcade has opened in Wellington". www.stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- "WILLIS LANE". www.willislane.nz. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- Talbot, Jillian (24 November 2001). "State insurance tower gets makeover". Dominion. ProQuest 315348965.

- "Get the picture". The Press. 13 December 1989 – via Papers Past.