| This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

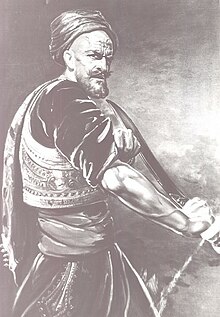

| Husein Gradaščević | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Dragon of Bosnia |

| Born | (1802-08-31)31 August 1802 Gradačac, Bosnia Eyalet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 17 August 1834(1834-08-17) (aged 31) Golden Horn, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Buried | Eyüp Cemetery, Istanbul |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles / wars | Bosnian uprising (1831–32) |

| Children | Muhamed-beg Gradaščević Šefika Gradaščević |

Husein Gradaščević (Husein-kapetan) (31 August 1802 – 17 August 1834) was an Ottoman Bosnian military commander who led an uprising against the Tanzimat, political reforms in the Ottoman Empire aimed at reducing Bosnian autonomy within Osmanli sultanate beside introduction of novel Western customs of governance. Born into a Bosnian noble family, Gradaščević became the captain of Gradačac in the early 1820s, succeeding his relatives (among whom was his father) in the position. He grew up surrounded by a political climate of turmoil in the western reaches of the Ottoman Empire. With the Russo-Turkish war (1828–29), Gradaščević's importance rose; the Bosnian governor gave him the task of mobilizing an army between the Drina and Vrbas.

By 1830, Gradaščević became the spokesman of all Ottoman captains in Bosnia and coordinated the defence in light of a possible Serbian invasion. Sparked by Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II's reforms that abolished the Janissaries and weakened the privileges of the nobility, and the autonomy and territory granted to the Principality of Serbia, much of the Bosnian nobility united and revolted. Gradaščević was chosen as the leader and claimed the title of Vizier. This uprising, with goals of autonomy, lasted three years and included the termination of Ottoman loyals mainly in Herzegovina. Among notable accomplishments, Gradaščević led forces victorious against the Ottoman field marshal in Kosovo. The uprising failed, and all captaincies were abolished by 1835. Temporarily exiled to Austria, he negotiated his return with the Sultan and was allowed to enter all of the Ottoman Empire except Bosnia. He died under controversial circumstances in 1834 and was buried in the Eyüp Cemetery in Istanbul.

Gradaščević received the honorific "the Dragon of Bosnia" (Zmaj od Bosne), and is considered a Bosniak national hero.

Early and personal life

Gradaščević's family originates from Buda in present-day Hungary, who came to Bosnia in the late 17th century.

Husein was born in the town of Gradačac (in northern Bosnia), to Osman and his wife Touley-hanuma in 1802, at the Gradaščević family house. Outside of family tradition and folklore invented much later, little is known of his childhood. It is said that he spent much time around the family fort while it was undergoing renovations. He grew up during turbulent times and taking into account his father's military experience and brother Osman's services during the 1813 war against Serbia, young Husein surely heard many first-hand accounts that shaped his personality.

Osman senior died in 1812 when Husein was merely ten years old. Certain scholars have argued that his mother was also dead by then, although some family traditions claim otherwise. By all accounts, his mother had a strong influence on Husein's upbringing. Upon his father's death, Husein deferred to his eldest brother Murat because of his age and status as successor to the Gradačac captaincy Husein Gradaščević rose to the head of the Gradačac military captaincy only after his brother Murat was poisoned in the 1821 by rival aristocrats attempting to gain the favour of the desperate Grand Vizier.

Husein married Hanifa, sister of Captain Mahmud of Derventa, at an early age. Although the exact date is unknown, his son Muhamed-beg Gradaščević was probably born no later than 1822 when Husein himself was twenty years old. The pair would also have a daughter, Šefika, born in 1833. Neither Muhamed nor Šefika were known to have had children themselves.

Gradačac captaincy

When Husein took over the Gradačac captaincy, he focused most of his attention on the administration of internal affairs. Notably, all of Husein's construction projects were related to the city of Gradačac and its immediate area. During his rule, Gradačac further expanded its status as one of the most prosperous captaincies in Bosnia.

The first and most notable construction was that of the Gradačac Castle. The fort had existed for decades and was subject to extensive renovations since the time of Captain Mehmed in 1765. Husein's father Osman and brother Murat had done some work as well, in 1808 and 1818–19 respectively. However, the exact nature of Husein's contribution is unknown. The castle's tower has long been associated with Husein but architectural evidence points to the tower existing alongside the rest of the complex from earlier times. It seems likely that Husein was merely responsible for a significant renovation of the tower that lingered in the people's memory.

Husein did have a new castle built, in a large project which included the construction of an artificial island surrounded by a moat up to 100 meters wide and of great depth. The castle was named Čardak and the surrounding village quickly derived its name from it. The walls were oval, the entire structure being seventeen meters long and eight meters wide. The complex and area also included a mosque, wells, a fishery, and hunting grounds.

Within the Gradačac city walls, Husein's most significant contribution to the city was the clock tower (Bosnian: sahat-kula) which was built in 1824. The object's base is 5.5 by 5.5 meters, while the height is 21.50 meters. It was the last object of this type to be built in Bosnia.

Some 40 to 50 meters outside the city walls lies Husein's greatest architectural contribution to Gradačac: the Husejnija mosque. Built in 1826, it features an octagonal dome roof and a particularly high minaret of 25 m. Three smaller octagonal domes are found above the verandah. Islamic decorations and artistry are seen on the door and surrounding wall as well as the interior. The entire complex is surrounded by a small stone wall and gate.

Husein's rule in Gradačac was also notable because of his tolerance towards the Christian populace under his jurisdiction; both Catholic and Orthodox. Though social norms of the time dictated that the Ottoman sultan's official approval was necessary for the construction of any non-Islamic religious buildings, Husein approved the construction of several such buildings without it. A Catholic school was built in the village of Tolisa in 1823, followed by a large church that could hold 1,500 people. Another two Catholic churches were built in the villages of Dubrave and Garevac, while an Orthodox church was built in the hamlet of Obudovac. During Husein's captaincy, the Christians in Gradačac were known to be the most satisfied in Bosnia.

Husein entered the higher political scene in Bosnia in 1827, largely due to the impending Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829) and his role in preparing the defence of the boundaries of Bosnia. Upon receiving orders from the Bosnian vizier Abdurahim Pasha, Husein mobilized the Gradačac populace and strengthened his defences. During talks held in Sarajevo between the vizier and the Bosnian captains, it is said that Husein stayed the longest to discuss strategy. He was appointed commander of an army that he was to mobilize from the lands between the Drina to the Vrbas. By all accounts, he did a satisfactory job. However, in mid-June 1828, Husein had to rush to Sarajevo with a small accompanying force to get the vizier to safety following a revolt among the troops.

By 1830, Husein had risen to new political heights as he was able to speak on behalf of all (or at least most of) the captains of Bosnia. At that time, he was coordinating the defence of Bosnia against a possible invasion by Serbia, as well as taking it upon himself to address Austrian authorities and warn them against any incursion across the Sava. The authority he wielded in the later years of his captaincy in Gradačac explains the great role he was to have in the years to follow.

Rumelian instability and Bosnian uprising

| This section should include a summary of Bosnian uprising (1831–32). See Misplaced Pages:Summary style for information on how to incorporate it into this article's main text. (January 2018) |

In the late 1820s, Sultan Mahmud II reintroduced a set of reforms that called for further expansion of the centrally controlled army (nizam), new taxes and more Ottoman bureaucracy. These reforms weakened the special status and privileges of the Bosnian Muslim nobility. Many Bosnian leaders had also been disappointed by Ottoman negligence to the plight of the Muslim refugees arriving from the Principality of Serbia. Contrary to popular belief, however, Husein Gradaščević was not greatly opposed to these reforms.

In 1826, during the Auspicious Incident, Sultan Mahmud II abolished the Janissaries, through the use of military force, executions and exile. Mahmud II then banned the revered Bektashi Order and decreed his Turkish commanders to launch campaigns against prominent Balkan Muslim leaders causing great instability in Rumelia. Gradaščević's immediate reaction to the abolition of the Janissaries was not unlike that of the rest of the Bosnian aristocracy; Gradaščević threatened with military force to subdue anybody opposed to the Sarajevo Janissaries. When the Janissaries killed naqib al-ashraf Imam Nurudin-effendi Šerifović, however, his tone shifted and he rapidly distanced himself from their cause. Gradaščević did realize that economic hardship was the main reason for Janissary dissent. After this, Gradaščević generally maintained good relations with imperial authorities in Bosnia. When Abdurahim Pasha became vizier in 1827, Gradaščević was said to have become one of his more trusted advisors. This culminated in Gradaščević's large role in the Bosnian mobilization for the Russo-Ottoman war. Following a riot in the Sarajevo camp during these preparations, Gradaščević even provided shelter for the ousted Abdurahim Pasha in Gradačac before assisting him in his escape from the country. Gradaščević was also relatively loyal to Abdurahim's successor, Namık Pasha, reinforcing Ottoman garrisons in Šabac upon his orders.

The turning point for Gradaščević came with the end of the Russo-Ottoman War and the Treaty of Adrianople on 14 September 1829. According to the provisions of the treaty, the Ottoman Empire had to grant autonomy to Serbia, and also cede it six districts. This outraged the Bosnian nobility, launching numerous protests.

Between 20 and 31 December 1830, Gradaščević hosted a gathering of Bosniak aristocrats in Gradačac. A month later, from 20 January to 5 February, another meeting was held in Tuzla to prepare for a revolt. From there, a call was issued to the Bosnian Muslim populace asking them to rise to the defence of Bosnia. It was then that the popular Gradaščević was unofficially chosen to head the rebellion. Further details of this meeting are murky and disputable. According to certain contemporary sources, their demands from Constantinople were:

- Repeal the privileges granted to Serbia and, in particular, return the six districts to Bosnia.

- Cease the implementation of the nizam military reforms.

- End the governorship of the Bosnia Eyalet and accept the implementation of an autonomous Bosnian government headed by a local leader. In return, Bosnia would pay a yearly tribute.

Another outcome of the Tuzla meeting was an agreement that another general meeting should be held in Travnik. Since Travnik was the seat of the Bosnia Eyalet and of the vizier, the planned meeting was in effect a confrontation with Ottoman authority. Gradaščević thus asked all involved to help assemble an army beforehand. On 29 March 1831, Gradaščević set out towards Travnik with some 4,000 men.

Upon hearing the word of the oncoming force, Namık Pasha is said to have gone to the Travnik fort and called the Sulejmanpašić brothers to his aid. When the rebel army arrived in Travnik they fired several warning shots at the castle, warning the vizier that they were prepared for a military encounter. Meanwhile, Gradaščević sent a detachment of his forces, under the command of Memiš-aga of Srebrenica, to meet Sulejmanpašić's reinforcements. The two sides met at Pirot, on the outskirts of Travnik, on 7 April. There, Memiš-aga defeated the Sulejmanpašić brothers and their 2,000-man army, forcing them to retreat and destroying the possessions of the Sulejmanpašić family. On 21 May, Namık Pasha fled to Stolac following a short siege. Soon afterwards, Husein Gradaščević was honourably proclaimed the "commander of Bosnia, chosen by the will of the people". On 31 May he demanded that all Bosnian aristocrats immediately join his army, and called on the general populace who wished to do so. Thousands rushed to join him, among them being numerous Christians, who were said to comprise up to a third of his total forces. Gradaščević split his army in two, leaving one part of it in Zvornik to defend against a possible Serbian incursion. With the bulk of the troops, he set out towards Kosovo to meet the Grand vizier, who had been sent with a large army to quell the rebellion. Along the way, he took the city of Peć with a 25,000-strong army and proceeded to Priština, where he set up his main camp.

The encounter with Grand Vizier Reşid Mehmed Pasha happened on 18 July near Štimlje. Although both armies were of roughly equal size, the Grand Vizier's troops had superior arms. Gradaščević sent a part of his army under the command of Ali Pasha Fidahić, the captain (kapetan) and sanjak-bey of Zvornik, ahead to meet Reşid Pasha's forces. Following a small skirmish, Fihadić feigned a retreat. Thinking that victory was within reach, the Grand Vizier sent his cavalry and artillery into forested terrain. Gradaščević immediately took advantage of this tactical error and executed a punishing counterattack with the bulk of his forces, almost annihilating the Ottoman forces. Reşid Pasha himself was injured and barely escaped with his life.

Following claims from the Grand Vizier that the Sultan would meet all Bosnian demands if the rebel army would return home, Gradaščević and his army turned back. On 10 August the leadership of the rebellion met at Priština and decided that Gradaščević be declared Vizier of Bosnia. Gradaščević refused at first but eventually accepted. This was made official at an assembly held in Sarajevo on 12 September, where in front of the Tsar's Mosque, those present swore on the Quran to be loyal to Gradaščević and declared that, despite potential failure and death, there would be no turning back.

At this point, Gradaščević was not only the supreme military commander but Bosnia's leading civilian authority as well. He established a court around him, and after initially making himself at home in Sarajevo, he moved the centre of Bosnian politics to Travnik, making it the de facto capital of the rebel state. In Travnik, he established a divan, a Bosnian congress, which together with him made up the Bosnian government. Gradaščević also collected taxes at this time and executed various local opponents of the autonomy movement. He gained a reputation as a hero and a strong, brave, and decisive ruler. One anecdote that illustrates this is Captain Husein's alleged response to whether he was scared of waging war against the Ottoman Empire.

During this lull in armed conflict with the Ottomans, attention was turned to the autonomy movement's strong opposition in Herzegovina. A small campaign was launched against the region from three different directions:

- An army from Sarajevo was ordered to attack Stolac for a final encounter with Namik-paša, who had fled there following Gradaščević's capture of Travnik.

- An army from Krajina was to assist the Sarajevan forces in this endeavour.

- Armies from Posavina and south Podrinje were to attack Gacko and local captain Smail-aga Čengić.

As it happened, Namık Pasha had already abandoned Stolac, so this attack was put on hold. The attack on Gacko was a failure as the forces from Posavina and south Podrinje were defeated by Čengić's troops. There was one success, however; in October, Husein Gradaščević had deployed an army under the command of Ahmed-beg Resulbegović, who had put his life in danger while attempting to capture Trebinje from Resulbegović's loyalist and heavily armed cousins.

A Bosnian delegation reached the Grand Vizier's camp in Skopje in November and was promised that the Grand Vizier would insist to the Sultan to accept Bosnian demands and appoint Gradaščević as the official Vizier of an autonomous Bosnia. His true intentions, however, were manifested by early December when he attacked Bosnian rebel units stationed on the outskirts of Novi Pazar. Yet again, the rebel army handed a defeat to the imperial forces. Due to a particularly strong winter though, the Bosnian troops were forced to return home.

Meanwhile, in Bosnia, Gradaščević decided to carry on his campaign against the captains in Herzegovina that were loyal to the Sultan, despite the unfavourable climate. The captain of Livno, Ibrahim-beg Fidrus, was ordered to launch a final attack against the local captains and to thus end all domestic opposition to the autonomy movement. To achieve this, Fidrus first attacked Ljubuški and the local captain Sulejman-beg, which he defeated and then secured the whole of Herzegovina except Stolac in the process. Unfortunately, the rebel detachments that laid siege to the Stolac Fortress met cannon fire and ambushes organized by Ali-paša Rizvanbegović in early March of the next year. Receiving information that the Bosnian ranks were depleted due to the winter, Rizvanbegović broke the siege, counterattacking the rebels and dispersing their forces; in doing so he proved that his fortress at Stolac was nearly impregnable. Husein Gradaščević, knowing of the eventual outcome, sent another well-equipped force towards Stolac from Sarajevo, under the command of Mujaga Zlatar, but it was ordered back on 16 March after receiving news of a major offensive on Bosnia being planned by the Grand Vizier.

The Ottoman campaign began in early February. The Grand Vizier sent two armies: one from Vučitrn and one from Shkodër. Both armies headed toward Sarajevo, and Gradaščević sent an army of around 10,000 men to meet them. When the Vizier's troops succeeded in crossing the Drina, Gradaščević ordered 6,000 men under Ali-paša Fidahić to meet them in Rogatica while units stationed in Višegrad were to head to Pale on the outskirts of Sarajevo. The encounter between the two sides finally happened on the Glasinac plains to the east of Sarajevo, near Sokolac, at the end of May. The Bosnian army was led by Gradaščević himself, while the Ottoman troops were under the command of Kara Mahmud Hamdi-paša, the new imperially recognized vizier of Bosnia. In this first encounter, Gradaščević was forced to retreat to Pale. The fighting continued in Pale and Gradaščević was once again forced to retreat; this time to Sarajevo. There, a council of captains decided that the fight would continue.

By 1832, after a series of smaller clashes, a decisive battle occurred outside Sarajevo; although Husein Gradaščević was initially successful, he was defeated when Serbian rebels arrived and sided with and reinforced the forces of Mahmud II.

The final battle was played out on 4 June at Stup, a small locality on the road between Sarajevo and Ilidža. After a long, intense battle, it seemed Gradaščević had once again defeated the Sultan's army. Near the very end, however, Herzegovinian troops under the command of Ali-paša Rizvanbegović and Smail-aga Čengić broke through defences Gradaščević had set up on his flank and joined the fighting. Overwhelmed by the unexpected attack from behind, the rebel army was forced to retreat into the city of Sarajevo itself. It was decided that further military resistance would be futile. Gradaščević fled to Gradačac as the imperial army entered the city on 5 June and prepared to march on Travnik. Upon realizing the difficulties that his home and family would experience if he stayed there, Gradaščević decided to leave Gradačac and continue on to Austrian lands instead.

Exile and death

If the choice to flee Bosnia was not already clear, the Sultan's furious fatwa declaring Gradaščević "no good", an "evil-doer", a "traitor", a "criminal" and a "rebel" may have convinced Gradaščević to leave. Due to various customs and procedures, however, Gradaščević's departure from Bosnia was held up for several days. After pleading with Austrian officials to ease their restrictions, Gradaščević finally reached the Sava River boundary with a large party of followers on 16 June. He crossed the river into Habsburg lands the same day, along with some 100 followers, servants, and family. Though he expected to be treated as a Bosnian vizier, he instead found himself held in quarantine in Slavonski Brod for nearly a month, with his weapons and many of his possessions taken away.

Gradaščević and other rebels managed to flee across the Sava to Vinkovci and then Osijek, in Austrian territory. Some 66 men, 12 women, 135 servants and 252 horses accompanied him.

Austrian officials faced constant pressure from the Ottoman government to move Gradaščević as far away from the border as possible. On 4 July he was moved to Osijek where he essentially lived in internment. His communications with the rest of his family and social circle were severely limited and he complained about his treatment to the authorities several times. His conditions would eventually improve, and before he left Osijek he remarked to local officials that he had enjoyed his stay there. Although intensely homesick and only partially in control of his destiny, Gradaščević retained his pride and dignity. He was said to have lived a luxurious life that included jousting competitions with his companions.

In late 1832, he agreed to return to Ottoman territory to receive a ferman of pardon from the Sultan. The terms, read to him in Zemun, were very harsh, insisting that Gradaščević not only never return to Bosnia, but also never to set foot on the European lands of the Ottoman Empire either. Disappointed, Gradaščević was forced to obey the terms and rode on to Belgrade. He entered the city on 14 October in the manner of a true vizier, riding a horse decked out in silver and gold and accompanied by a large procession. He was greeted as a hero by the Muslims in Belgrade and treated like an equal by the local pasha. Gradaščević stayed in the city for two months, during which his health deteriorated (as was documented by the local doctor Bartolomeo Kunibert). He left the city for Constantinople in December, but as his daughter was still very young, his wife remained in Belgrade, joining him in the spring of the following year.

In Constantinople, Gradaščević lived in an old janissary barracks at atmejdan (Hippodrome square) while his family lived in a separate house nearby. He lived a relatively quiet life for the next two years, the only notable event being an offer from the Sultan for Gradaščević to become a high-ranking pasha in the Nizami army; an offer that Gradaščević indignantly refused.

He died in Constantinople in 1834 at the age of 32.

Legacy

Upon his death, he became something of a martyr for Bosnian pride. There was a well-known saying among Bosniaks that for years after his death not a single man among our people would be able to hear his name and not shed a tear. This positive sentiment was not exclusive to the Muslim population, as Christians from Posavina are thought to have shared a similar view for decades.

Although a majority of the Bosniaks in Herzegovina supported the cause of Husein Gradaščević, some of its ruling kapetans such as Ali-paša Rizvanbegović supported Sultan Mahmud II for their gains, in the years that followed the Herzegovina kapetans suffered during the Herzegovina Uprising (1875–1878) mainly due to the lack of a centralised authority in Bosnia Eyalet.

The first historical literature written about Gradaščević can be found in Safvet-beg Bašagić's work from 1900, A short introduction into the past of Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, due to historical differences between the Bašagić and Gradaščević families, Safvet-beg's view of Husein-kapetan is somewhat opinionated. A year later, Gradaščević was mentioned by Kunibert in his works on the first Serbian Uprising, which painted a positive picture of Gradaščević as a tragic hero.

In the years that followed, Gradaščević was mentioned, either specifically or in the context of the movement he led, by D. Pavlović, Slavko Kaluđerčić, and Hamdija Kreševljaković. The general sentiment was that the autonomy movement was merely a reaction to imperial reforms by the Bosnian upper class. This view would be predominant among historians for decades. Gradaščević had a minor resurgence during World War II when Ustaše launched a propaganda-rooted proposal to bring his remains back to Sarajevo.

During the time of Communist Yugoslavia, Gradaščević and his movement were rarely mentioned. The perceived upper-class resistance to the implementation of modern reforms did not go well with communist ideology. Gradaščević was briefly mentioned in such a light by Avdo Sućeska in his 1964 work on Bosnian captains. It would be another 24 years before Gradaščević was mentioned again. This time it was in Galib Šljiva's 1988 work on Bosnia in the first half of the 19th century. Though several historiographical controversies were resolved, there was no significant shift in the perception of Gradaščević.

Since the Yugoslav Wars and the Bosniak National Awakening, Gradaščević and his movement have experienced a rebirth among historians and the common public alike. Works by Ahmed S. Aličić, Mustafa Imamović, and Husnija Kamberović have all cast Gradaščević in a more positive light. Gradaščević is once again widely considered the greatest Bosniak national hero and is a symbol of national pride and spirit. The main streets in Gradačac and Sarajevo are both named after him, as well as numerous other places in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Annotations

- In Bosnian, he is referred to as Husein-kapetan (Serbian Cyrillic: Хусеин-капетан), which includes his given name and Ottoman rank, captain. He is also known by the nickname "the Dragon of Bosnia" (Zmaj od Bosne). The surname Gradaščević is a byname derived from Gradačac.

References

- Filipović 1951, p. 68.

- Donia 2006, p. 29.

- Donia, R.J.; Van Antwerp Fine, J. (1994). Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. Hurst. p. 62. ISBN 978-1850652120. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Zulfikarpašić, A.; Djilas, M.; Gaće, N. (1998). The Bosniak. Hurst. p. 17. ISBN 978-1850653394. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- Đordić 1996, p. 60.

- Donia, R.J. (2006). Sarajevo: A Biography. University of Michigan Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0472115570. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

Sources

- Kamberović, Husnija (2002). Husein-kapetan Gradaščević (1802–1834): Biografija: uz dvjestu godišnjicu rođenja [Husein-kapetan Gradaščević (1802–1834): Biography: on the occasion of the bicentennial of his birth] (pdf) (in Bosnian). Gradačac: BZK "Preporod" (published January 2002). ISBN 9958-812-03-7.

- Donia, Robert J. (2006). Sarajevo: A Biography. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11557-0.

- Fatma Sel Turhan (2014). The Ottoman Empire and the Bosnian Uprising: Janissaries, Modernisation and Rebellion in the Nineteenth Century. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-111-4.

- Đordić, Marjan (1996). Bosanska Posavina: povijesno-zemljopisni pregled. Polion. ISBN 978-9536199013.

- Filipović, Milenko (1951). Цинцари у Босни, Зборник радова [Aromanians in Bosnia: a collection of papers] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Etnografski institut.

- Sadik Šehić (1991). Zmaj od Bosne: Husein-kapetan Gradaščević. Front Slobode.

- Teinović, Bratislav (2019). Nacionalno-politički razvoj Bosne i Hercegovine u posljednjem vijeku turske vladavine (1800-1878) [The national-political development of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the last century of the Turkish rule (1800-1878)] (in Serbian). Banja Luka: Faculty of Humanities, University of Banja Luka.

Further reading

- Šehić, S., Bilajac, I., Hebib, A. and Lindemann, F., 1994. Zmaj od Bosne: Husein-kapetan Gradaščević između legende i povijesti. Bosanska riječ.

- Aličić, Ahmed S. (1996). Pokret za autonomiju Bosne od 1831. do 1832. godine. Sarajevo: Orijentalni institut.

- Imamović, Mustafa. (1997). Historija Bošnjaka. Borba za autonomiju Bosne – Husein-kapetan Gradaščević. Sarajevo: BZK Preporod.

- Vrijeme nemira u Bosni u prvoj polovini XIX stoljeca i Husein-beg Gradascevic.

External links

- Short biography on site about Gradačac Archived 2005-11-03 at the Wayback Machine (in Bosnian)

- Short story about Husein Gradaščević's life (in Bosnian)

- Otpori i reforme u Bosni i Hercegovini 1815–1878 (in Bosnian)