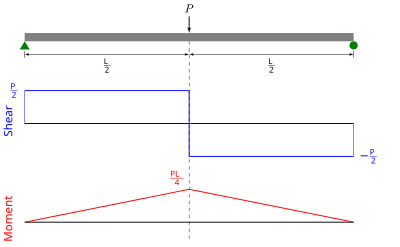

In solid mechanics, a bending moment is the reaction induced in a structural element when an external force or moment is applied to the element, causing the element to bend. The most common or simplest structural element subjected to bending moments is the beam. The diagram shows a beam which is simply supported (free to rotate and therefore lacking bending moments) at both ends; the ends can only react to the shear loads. Other beams can have both ends fixed (known as encastre beam); therefore each end support has both bending moments and shear reaction loads. Beams can also have one end fixed and one end simply supported. The simplest type of beam is the cantilever, which is fixed at one end and is free at the other end (neither simple nor fixed). In reality, beam supports are usually neither absolutely fixed nor absolutely rotating freely.

The internal reaction loads in a cross-section of the structural element can be resolved into a resultant force and a resultant couple. For equilibrium, the moment created by external forces/moments must be balanced by the couple induced by the internal loads. The resultant internal couple is called the bending moment while the resultant internal force is called the shear force (if it is transverse to the plane of element) or the normal force (if it is along the plane of the element). Normal force is also termed as axial force.

The bending moment at a section through a structural element may be defined as the sum of the moments about that section of all external forces acting to one side of that section. The forces and moments on either side of the section must be equal in order to counteract each other and maintain a state of equilibrium so the same bending moment will result from summing the moments, regardless of which side of the section is selected. If clockwise bending moments are taken as negative, then a negative bending moment within an element will cause "hogging", and a positive moment will cause "sagging". It is therefore clear that a point of zero bending moment within a beam is a point of contraflexure—that is, the point of transition from hogging to sagging or vice versa.

Moments and torques are measured as a force multiplied by a distance so they have as unit newton-metres (N·m), or pound-foot (lb·ft). The concept of bending moment is very important in engineering (particularly in civil and mechanical engineering) and physics.

Background

Tensile and compressive stresses increase proportionally with bending moment, but are also dependent on the second moment of area of the cross-section of a beam (that is, the shape of the cross-section, such as a circle, square or I-beam being common structural shapes). Failure in bending will occur when the bending moment is sufficient to induce tensile/compressive stresses greater than the yield stress of the material throughout the entire cross-section. In structural analysis, this bending failure is called a plastic hinge, since the full load carrying ability of the structural element is not reached until the full cross-section is past the yield stress. It is possible that failure of a structural element in shear may occur before failure in bending, however the mechanics of failure in shear and in bending are different.

Moments are calculated by multiplying the external vector forces (loads or reactions) by the vector distance at which they are applied. When analysing an entire element, it is sensible to calculate moments at both ends of the element, at the beginning, centre and end of any uniformly distributed loads, and directly underneath any point loads. Of course any "pin-joints" within a structure allow free rotation, and so zero moment occurs at these points as there is no way of transmitting turning forces from one side to the other.

It is more common to use the convention that a clockwise bending moment to the left of the point under consideration is taken as positive. This then corresponds to the second derivative of a function which, when positive, indicates a curvature that is 'lower at the centre' i.e. sagging. When defining moments and curvatures in this way calculus can be more readily used to find slopes and deflections.

Critical values within the beam are most commonly annotated using a bending moment diagram, where negative moments are plotted to scale above a horizontal line and positive below. Bending moment varies linearly over unloaded sections, and parabolically over uniformly loaded sections.

Engineering descriptions of the computation of bending moments can be confusing because of unexplained sign conventions and implicit assumptions. The descriptions below use vector mechanics to compute moments of force and bending moments in an attempt to explain, from first principles, why particular sign conventions are chosen.

Computing the moment of force

An important part of determining bending moments in practical problems is the computation of moments of force. Let be a force vector acting at a point A in a body. The moment of this force about a reference point (O) is defined as

where is the moment vector and is the position vector from the reference point (O) to the point of application of the force (A). The symbol indicates the vector cross product. For many problems, it is more convenient to compute the moment of force about an axis that passes through the reference point O. If the unit vector along the axis is , the moment of force about the axis is defined as

where indicates the vector dot product.

Example

The adjacent figure shows a beam that is acted upon by a force . If the coordinate system is defined by the three unit vectors , we have the following

Therefore,

The moment about the axis is then

Sign conventions

The negative value suggests that a moment that tends to rotate a body clockwise around an axis should have a negative sign. However, the actual sign depends on the choice of the three axes . For instance, if we choose another right handed coordinate system with , we have

Then,

For this new choice of axes, a positive moment tends to rotate body clockwise around an axis.

Computing the bending moment

In a rigid body or in an unconstrained deformable body, the application of a moment of force causes a pure rotation. But if a deformable body is constrained, it develops internal forces in response to the external force so that equilibrium is maintained. An example is shown in the figure below. These internal forces will cause local deformations in the body.

For equilibrium, the sum of the internal force vectors is equal to the negative of the sum of the applied external forces, and the sum of the moment vectors created by the internal forces is equal to the negative of the moment of the external force. The internal force and moment vectors are oriented in such a way that the total force (internal + external) and moment (external + internal) of the system is zero. The internal moment vector is called the bending moment.

Though bending moments have been used to determine the stress states in arbitrary shaped structures, the physical interpretation of the computed stresses is problematic. However, physical interpretations of bending moments in beams and plates have a straightforward interpretation as the stress resultants in a cross-section of the structural element. For example, in a beam in the figure, the bending moment vector due to stresses in the cross-section A perpendicular to the x-axis is given by

Expanding this expression we have,

We define the bending moment components as

The internal moments are computed about an origin that is at the neutral axis of the beam or plate and the integration is through the thickness ()

Example

In the beam shown in the adjacent figure, the external forces are the applied force at point A () and the reactions at the two support points O and B ( and ). For this situation, the only non-zero component of the bending moment is

where is the height in the direction of the beam. The minus sign is included to satisfy the sign convention.

In order to calculate , we begin by balancing the forces, which gives one equation with the two unknown reactions,

To obtain each reaction a second equation is required. Balancing the moments about any arbitrary point X would give us a second equation we can use to solve for and in terms of . Balancing about the point O is simplest but let's balance about point A just to illustrate the point, i.e.

If is the length of the beam, we have

Evaluating the cross-products:

If we solve for the reactions we have

Now to obtain the internal bending moment at X we sum all the moments about the point X due to all the external forces to the right of X (on the positive side), and there is only one contribution in this case,

We can check this answer by looking at the free body diagram and the part of the beam to the left of point X, and the total moment due to these external forces is

If we compute the cross products, we have

Thanks to the equilibrium, the internal bending moment due to external forces to the left of X must be exactly balanced by the internal turning force obtained by considering the part of the beam to the right of X

which is clearly the case.

Sign convention

In the above discussion, it is implicitly assumed that the bending moment is positive when the top of the beam is compressed. That can be seen if we consider a linear distribution of stress in the beam and find the resulting bending moment. Let the top of the beam be in compression with a stress and let the bottom of the beam have a stress . Then the stress distribution in the beam is . The bending moment due to these stresses is

where is the area moment of inertia of the cross-section of the beam. Therefore, the bending moment is positive when the top of the beam is in compression.

Many authors follow a different convention in which the stress resultant is defined as

In that case, positive bending moments imply that the top of the beam is in tension. Of course, the definition of top depends on the coordinate system being used. In the examples above, the top is the location with the largest -coordinate.

See also

- Buckling

- Deflection including deflection of a beam

- Twisting moment

- Shear and moment diagrams

- Stress resultants

- First moment of area

- Influence line

- Second moment of area

- List of area moments of inertia

- Wing bending relief

References

- ^ Gere, J.M.; Timoshenko, S.P. (1996), Mechanics of Materials:Forth edition, Nelson Engineering, ISBN 0534934293

- ^ Beer, F.; Johnston, E.R. (1984), Vector mechanics for engineers: statics, McGraw Hill, pp. 62–76

- Baker, Daniel W.; Haynes, William. Statics: Internal Loads.

External links

| Structural engineering | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic analysis | |||||||

| Static analysis | |||||||

| Structural elements |

| ||||||

| Theories | |||||||

be a force vector acting at a point A in a body. The moment of this force about a reference point (O) is defined as

be a force vector acting at a point A in a body. The moment of this force about a reference point (O) is defined as

is the moment vector and

is the moment vector and  is the position vector from the reference point (O) to the point of application of the force (A). The

is the position vector from the reference point (O) to the point of application of the force (A). The  symbol indicates the vector cross product. For many problems, it is more convenient to compute the moment of force about an axis that passes through the reference point O. If the unit vector along the axis is

symbol indicates the vector cross product. For many problems, it is more convenient to compute the moment of force about an axis that passes through the reference point O. If the unit vector along the axis is  , the moment of force about the axis is defined as

, the moment of force about the axis is defined as

indicates the vector

indicates the vector  . If the coordinate system is defined by the three unit vectors

. If the coordinate system is defined by the three unit vectors  , we have the following

, we have the following

is then

is then

, we have

, we have

)

)

) and the reactions at the two support points O and B (

) and the reactions at the two support points O and B ( and

and  ).

For this situation, the only non-zero component of the bending moment is

).

For this situation, the only non-zero component of the bending moment is

![{\displaystyle \mathbf {M} _{xz}=-\left\,dz\right]\mathbf {e} _{z}\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f580ca80ae5403763cf0a628f588be42729aa2b1)

direction of the beam. The minus sign is included to satisfy the sign convention.

direction of the beam. The minus sign is included to satisfy the sign convention.

, we begin by balancing the forces, which gives one equation with the two unknown reactions,

, we begin by balancing the forces, which gives one equation with the two unknown reactions,

and

and  in terms of

in terms of

is the length of the beam, we have

is the length of the beam, we have

side), and there is only one contribution in this case,

side), and there is only one contribution in this case,

and let the bottom of the beam have a stress

and let the bottom of the beam have a stress  . Then the stress distribution in the beam is

. Then the stress distribution in the beam is  . The bending moment due to these stresses is

. The bending moment due to these stresses is

is the

is the  is defined as

is defined as