| Black Orchid | |

|---|---|

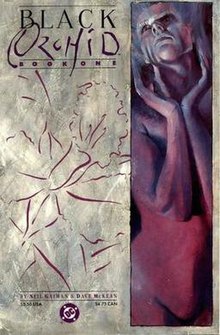

Cover of Black Orchid #1 (December 1988) by Dave McKean. Cover of Black Orchid #1 (December 1988) by Dave McKean. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| Format | Limited series |

| Genre | |

| Publication date | December 1988 – February 1989 |

| No. of issues | 3 |

| Main character(s) | |

| Creative team | |

| Written by | Neil Gaiman |

| Artist(s) | Dave McKean |

Black Orchid is an American comic book written by Neil Gaiman with art by Dave McKean. It was published by DC Comics as a three-issue limited series from December 1988 to February 1989, and was later reprinted in trade paperback form. Black Orchid follows two girls, Flora and Suzy, who awaken in a greenhouse. Their journey to find out who they are leads them into contact with DC Universe figures like Batman and Swamp Thing, but also into conflict with criminal mastermind Lex Luthor, who seeks them for his own interests.

Gaiman and McKean developed the series after meeting with Jenette Kahn, Dick Giordano, and Karen Berger in early 1987. The two pitched several ideas for series, but were ultimately assigned Black Orchid because all other characters they wanted to work on were in use at the time. They produced the series' concept within two days and won approval from DC Comics. DC nearly canceled the series due to fears it would fail commercially, but relented after McKean finished the art. Gaiman later reworked some cut characters and concepts into a pitch for a new series, which became his critically acclaimed Sandman.

Despite DC's concerns, Black Orchid sold well and was positively received. Critics feel the story has held up well for one of Gaiman's earliest works. Black Orchid helped bolster Gaiman's career and established many themes that became common in his later stories. It also inspired a short-lived ongoing series published under DC's alternative imprint Vertigo from September 1993 to June 1995.

Publication history

Background

The superhero Black Orchid, created by Sheldon Mayer and Tony Zuniga, first appeared in Adventure Comics #428 (June 1973), and was published by DC Comics. She was the first superhero to debut as the cover feature of the series since Starman in 1941; she was not given an origin story and her personal life was not shown. After a three-issue run in Adventure Comics, Black Orchid quickly faded into obscurity, but sporadically made guest appearances in other DC publications.

Neil Gaiman is a popular British author who has written comics for numerous publishers, but is best known for his work at DC, which includes high-profile comics like Batman, The Books of Magic, and The Sandman. Gaiman had wanted to write comics since he was a child, but became especially interested after forming a friendship with Alan Moore in the 1980s. Gaiman's first comics were published in 2000 A.D., but he quit after his third piece came out, upset that his artist ignored most of his script directions. Gaiman met painter Dave McKean while working on an unreleased comic called Borderline; the two then went on to produce Violent Cases.

Development

In early 1987, Gaiman learned that DC's president Jenette Kahn, executive editor Dick Giordano, and editor Karen Berger were in London, so he managed to schedule an appointment with them. Gaiman and McKean pitched series featuring John Constantine, the Sandman, the Phantom Stranger, and Green Arrow, among others. At the time, Jamie Delano had been developing the Constantine series Hellblazer, the Sandman was appearing in Justice Society of America, a Phantom Stranger limited series was in production, and Mike Grell was writing a Green Arrow series. Eventually, Gaiman got to the character at the bottom of his list, Black Orchid. Upon hearing the name, Berger, who did not know who Black Orchid was and misunderstood Gaiman because of his accent, asked "Blackhawk Kid? Who's he?" Giordano, on the other hand, knew who she was and gave Gaiman and McKean his approval.

As they walked away, McKean expressed disappointment that they were assigned Black Orchid, as he wished to produce a comic featuring Swamp Thing and rainforests. Gaiman promised McKean he would include them in the story. He was motivated by Berger's response to recreate Black Orchid in a new way. Gaiman had been interested by Moore's work on Swamp Thing and, like Moore, sought to explore the DC Universe using minor and obscure characters. Gaiman produced an outline for Black Orchid within a day and the next day McKean finished five paintings. They dropped them off at the hotel Kahn, Giordano, and Berger were staying at. In retrospect, Berger stated that the duo's quickness on Black Orchid's concepts was the reason DC took them seriously in later years.

DC commissioned Black Orchid as a three-issue limited series to debut in the 1988 holiday season. Gaiman considered it a realistic story. To set the tone for the series, he began it by killing the original Black Orchid and introducing her sisters. Then, he had the series explore the DC Universe while elaborating on Black Orchid's origin. As she had never been given a proper backstory, Gaiman decided to tie Black Orchid to Swamp Thing and Batman. He considered including characters and concepts from the 1974 Sandman series (including the Sandman, Brute, Glob, and the brothers Cain and Abel) in a scene for the first issue. The scene did not make it into later drafts because Roy Thomas was using the characters in Infinity, Inc. Gaiman used these concepts in a pitch for a new series, which became The Sandman. McKean's art, unlike other comics, combined paintings, photography, and sculptures. Some of his pages had as many as 12 panels.

After Gaiman and McKean finished the first issue, Gaiman received a phone call from a worried Berger. According to Gaiman, Berger said DC was considering placing Black Orchid on hold for at least a few years because it was expected to be a financial failure: comics featuring female characters did not sell well, and while Gaiman, McKean, and the Black Orchid character were virtually unknown, the project was as big as the influential Frank Miller series The Dark Knight Returns. DC wanted Gaiman to start working on an ongoing series and McKean to paint Grant Morrison's Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth so they could build reputations, and then return to Black Orchid afterwards. The postponing ultimately did not happen because Arkham Asylum began to experience delays, which allowed McKean to finish Black Orchid.

Publication

Black Orchid began its run in December 1988 and concluded in February 1989. The series was Gaiman's first work for DC. A collected edition was published in late 1991. A hardcover deluxe edition was published on April 4, 2012, under DC's Vertigo imprint. The series received another rerelease through DC Black Label on November 12, 2019.

Plot

Carl Thorne is released from prison and goes to see billionaire criminal mastermind Lex Luthor, with whom he previously had interactions. Luthor dismisses Thorne, distrusting him due to his troublesome past. Thorne retreats to a bar, where he gripes about Luthor and blames his failures on his ex-wife Susan Linden. Meanwhile, Linden—the superhero Black Orchid—is killed while spying on Luthor's organized crime syndicate; afterward, Luthor's employee Mr. Sterling discovers she is a plant hybrid.

Elsewhere, an amnesiac young girl, Flora, awakens in a greenhouse. She wanders into a nearby house, where she meets Philip Sylvian, who recognizes her as Black Orchid. Sylvian explains that he and Linden were once romantically involved, but separated at the wishes of Linden's abusive father. Linden married Thorne, while Sylvian, Jason Woodrue, Pamela Isley, and Alec Holland worked together on advanced botanical biochemistry that led to Flora's creation; she is genetically Linden's sister. Only Sylvian remains his old self: Woodrue was incarcerated in Arkham Asylum; Isley became Poison Ivy; and Holland was allegedly murdered.

Flora falls asleep afterwards, and experiences Linden's memories in her dreams. Sylvian visits Linden's room, only to be attacked by Thorne. Thorne beats Sylvian and accuses him of stealing Linden from him. Thorne proceeds to the greenhouse, where he discovers statues of Linden. Thorne begins to destroy the statues before another girl—who insists on being called Suzy and also shares Linden's memories—appears. Thorne calls Luthor, who reluctantly comes to the scene. Luthor discovers that Sylvian died of his wounds and orders his men to throw Thorne in the nearby river. Flora saves Thorne before departing with Suzy; Luthor orders his staff to search for more like the girls.

Flora and Suzy travel to Gotham City, the location of Arkham, to converse with Woodrue. The girls are told that Woodrue left the asylum and denied access. Suzy goes to Slaughter Swamp, where she is kidnapped and sold to Luthor. Flora meets Batman, who deduces that she is related to Linden and gets her into Arkham. The Mad Hatter brings Flora to Isley, who is being held there. Isley explains her involvement with the other scientists but refuses to tell Flora who she is. Frustrated, Flora leaves, fails to save Suzy, and retreats to a graveyard.

Batman tells Flora that Holland is still alive and lives in the Louisiana swamplands. Black travels to Louisiana, where she meets Holland, who is now Swamp Thing. Holland explains to her that she is a reincarnation of Linden: Thorne murdered Linden, and Sylvian used her DNA and an orchid to recreate her as Black Orchid. When Linden was killed, another Black Orchid, in this case Flora, awoke.

Using their connections to the Green, Holland shows Flora where Suzy is located, and Flora saves her by knocking down a tree to stop the truck she is held in. The two escape to the Amazon rainforest, but Luthor tracks them and sends Sterling and a team to find them. While searching, Sterling's men are ambushed by Thorne as they approach the girls. Flora attempts to stop the fighting, but Sterling shoots Thorne in the chest. Thorne's death angers Flora, who sends Sterling off with a warning: if Luthor tries to interfere with her again, she will retaliate. Sterling and his men part ways, and Flora and Suzy fly back home.

Reception

Black Orchid has been well-received, with critics writing that, although one of Gaiman's early works, it has held up well. IGN summarized Black Orchid as a must-have and praised its writing and ending. They felt it was just "as unique and beautiful as the fictional flower that bears the title's name" and wrote that while it was not as good as Gaiman's The Sandman or Moore's Swamp Thing, it was still a fascinating and unique story. The Sequart Organization agreed and stated that it provided readers an intricate and vast world, something they considered rare for a relatively short series. Black Orchid was a commercial success. Don Markstein said that while the series did not make Black Orchid a household name, it helped expose her to many readers. The series has never been out of print since its initial publication. In addition, Black Orchid helped bolster Gaiman's career and established many themes that became common in his works.

Ongoing series

After DC launched its Vertigo imprint, it started publishing a Black Orchid ongoing series in September 1993. Gaiman had no involvement in the ongoing series as he was preoccupied writing The Sandman. McKean was working in England, so he was unable to provide any art besides covers. The new series was written by Dick Foreman with art by Jill Thompson and Rebecca Guay. The series ended in June 1995 after 22 issues. At the end of the series, Flora is killed, leaving Suzy the only surviving member of their species.

References

Footnotes

- Markstein, Don. "The Black Orchid (1973)". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- Lawson, Emma (March 30, 2017). "Reading List: The Ten Essential Neil Gaiman Comics". ComicsAlliance. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- "Fiction Book Review: Batman: Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader, the Deluxe Edition". Publishers Weekly. July 27, 2009. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- R. Parker, John (January 29, 2013). "Neil Gaiman's 'The Books of Magic' Reintroduced Fans to the Occult Corner of the DC Universe [Review]". ComicsAlliance. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ Grant 1994, p. 40.

- Olsen 2005, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Gaiman Berger 2010.

- ^ Markstein, Don. "The Black Orchid (1988)". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Means-Shannon, Hannah (April 12, 2013). "Neil Gaiman: The Early Years, Black Orchid's Passive and Impassive Universe Part 1". Sequart Organization. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Gaiman 1989.

- "An Interview With Neil Gaiman". Gothic Beauty. December 1, 2004. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Grant 1994, p. 41.

- Gaiman McKean 1988.

- Gaiman McKean 1989.

- Gaiman McKean 1991.

- "DC Comics' FULL February 2012 SOLICITATIONS". Newsarama. November 14, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- Hilgenberg, Josh (November 9, 2018). "DC Comics Is Releasing New Black Label Editions of Classic Titles". Paste. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Goldstein, Hilary (December 5, 2005). "Black Orchid Review". IGN. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- Mautner, Chris (January 25, 2010). "Comics College: Neil Gaiman". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Cronin, Brian (June 5, 2008). "Comic Book Urban Legends Revealed #158". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

Sources

- Olsen, Steven P. (2005). Neil Gaiman (Library of Graphic Novelists). New York, New York: Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-1404202856.

- Gaiman, Neil (October 19, 2010). The Sandman: Preludes & Nocturnes. Introduction: Karen Berger: DC Comics. ISBN 978-1401225759.

- Grant, Paul J. (December 1994). "Fables and Reflections". Wizard (48). Wizard Entertainment.

- Gaiman, Neil (w). "The Origin of the Comic You Are Now Holding (What It Is and How It Came to Be)" Sandman, no. 4 (April 1989). DC Comics.

- Gaiman, Neil (w), McKean, Dave (p). "One Thing is Certain..." Black Orchid, no. 1 (December 1988). DC Comics.

- Gaiman, Neil (w), McKean, Dave (p). "Yes..." Black Orchid, no. 3 (February 1989). DC Comics.

- Gaiman, Neil; McKean, Dave (September 1991). Black Orchid (1 ed.). DC Comics. ISBN 0-930289-55-2.

Further reading

- Means-Shannon, Hannah (April 26, 2013). "Neil Gaiman: The Early Years, Black Orchid (Part 2), "Gangsters and Scientists"". Sequart Organization. Retrieved September 7, 2018.