| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Product lifecycle" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

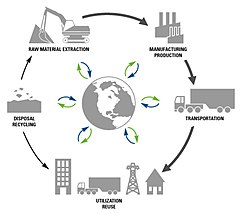

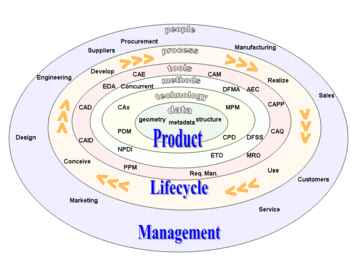

In industry, product lifecycle management (PLM) is the process of managing the entire lifecycle of a product from its inception through the engineering, design and manufacture, as well as the service and disposal of manufactured products. PLM integrates people, data, processes, and business systems and provides a product information backbone for companies and their extended enterprises.

History

The inspiration for the burgeoning business process now known as PLM came from American Motors Corporation (AMC). The automaker was looking for a way to speed up its product development process to compete better against its larger competitors in 1985, according to François Castaing, Vice President for Product Engineering and Development. AMC focused its R&D efforts on extending the product lifecycle of its flagship products, particularly Jeeps, because it lacked the "massive budgets of General Motors, Ford, and foreign competitors." After introducing its compact Jeep Cherokee (XJ), the vehicle that launched the modern sport utility vehicle (SUV) market, AMC began development of a new model, that later came out as the Jeep Grand Cherokee. The first part in its quest for faster product development was computer-aided design (CAD) software system that made engineers more productive. The second part of this effort was the new communication system that allowed conflicts to be resolved faster, as well as reducing costly engineering changes because all drawings and documents were in a central database. The product data management was so effective that after AMC was purchased by Chrysler, the system was expanded throughout the enterprise connecting everyone involved in designing and building products. While an early adopter of PLM technology, Chrysler was able to become the auto industry's lowest-cost producer, recording development costs that were half of the industry average by the mid-1990s.

Forms

PLM systems help organizations in coping with the increasing complexity and engineering challenges of developing new products for the global competitive markets.

Product lifecycle management (PLM) should be distinguished from 'product life-cycle management (marketing)' (PLCM). PLM describes the engineering aspect of a product, from managing descriptions and properties of a product through its development and useful life; whereas, PLCM refers to the commercial management of the life of a product in the business market with respect to costs and sales measures.

Product lifecycle management can be considered one of the four cornerstones of a manufacturing corporation's information technology structure. All companies need to manage communications and information with their customers (CRM-customer relationship management), their suppliers and fulfillment (SCM-supply chain management), their resources within the enterprise (ERP-enterprise resource planning) and their product planning and development (PLM).

One form of PLM is called people-centric PLM. While traditional PLM tools have been deployed only on the release or during the release phase, people-centric PLM targets the design phase.

As of 2009, ICT development (EU-funded PROMISE project 2004–2008) has allowed PLM to extend beyond traditional PLM and integrate sensor data and real-time 'lifecycle event data' into PLM, as well as allowing this information to be made available to different players in the total lifecycle of an individual product (closing the information loop). This has resulted in the extension of PLM into closed-loop lifecycle management (CL2M).

Benefits

Documented benefits of product lifecycle management include:

- Reduced time to market

- Increase full-price sales

- Improved product quality and reliability

- Reduced prototyping costs

- More accurate and timely requests for quote generation

- Ability to quickly identify potential sales opportunities and revenue contributions

- Savings through the re-use of original data

- A framework for product optimization

- Reduced waste

- Savings through the complete integration of engineering workflows

- Documentation that can assist in proving compliance for RoHS or Title 21 CFR Part 11

- Ability to provide contract manufacturers with access to a centralized product record

- Seasonal fluctuation management

- Improved forecasting to reduce material costs

- Maximize supply chain collaboration

Overview of product lifecycle management

Within PLM there are five primary areas;

- Systems engineering (SE) is focused on meeting all requirements, primarily meeting customer needs, and coordinating the systems design process by involving all relevant disciplines. An important aspect of lifecycle management is a subset within Systems Engineering called Reliability Engineering.

- Product and portfolio management (PPM) are focused on managing resource allocation, tracking progress, planning for new product development projects that are in process (or in a holding status). Portfolio management is a tool that assists management in tracking progress on new products and making trade-off decisions when allocating scarce resources.

- Product design (CAx) is the process of creating a new product to be sold by a business to its customers.

- Manufacturing process management (MPM) is a collection of technologies and methods used to define how products are to be manufactured.

- Product data management (PDM) is focused on capturing and maintaining information on products and/or services through their development and useful life. Change management is an important part of PDM/PLM.

Note: While application software is not required for PLM processes, the business complexity and rate of change requires organizations to execute as rapidly as possible.

Introduction to development process

The core of PLM (product lifecycle management) is the creation and central management of all product data and the technology used to access this information and knowledge. PLM as a discipline emerged from tools such as CAD, CAM and PDM, but can be viewed as the integration of these tools with methods, people and the processes through all stages of a product's life. It is not just about software technology but is also a business strategy.

For simplicity, the stages described are shown in a traditional sequential engineering workflow. The exact order of events and tasks will vary according to the product and industry in question but the main processes are:

- Conceive

- Specification

- Concept design

- Design

- Detailed design

- Validation and analysis (simulation)

- Tool design

- Realise

- Plan manufacturing

- Manufacture

- Build/Assemble

- Test (quality control)

- Service

- Sell and deliver

- Use

- Maintain and support

- Dispose

The major key point events are:

- Order

- Idea

- Kickoff

- Design freeze

- Launch

The reality is however more complex, people and departments cannot perform their tasks in isolation and one activity cannot simply finish, and the next activity start. Design is an iterative process, often designs need to be modified due to manufacturing constraints or conflicting requirements. Whether a customer order fits into the timeline depends on the industry type and whether the products are, for example, built to order, engineered to order, or assembled to order.

Phases of product lifecycle and corresponding technologies

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Many software solutions have been developed to organize and integrate the different phases of a product's lifecycle. PLM should not be seen as a single software product but as a collection of software tools and working methods integrated together to address either single stages of the lifecycle or connect different tasks or manage the whole process. Some software providers cover the whole PLM range while others have a single niche application. Some applications can span many fields of PLM with different modules within the same data model. An overview of the fields within PLM is covered here. The simple classifications do not always fit exactly; many areas overlap and many software products cover more than one area or do not fit easily into one category. It should also not be forgotten that one of the main goals of PLM is to collect knowledge that can be reused for other projects and to coordinate the simultaneous concurrent development of many products. It is about business processes, people, and methods as much as software application solutions. Although PLM is mainly associated with engineering tasks it also involves marketing activities such as product portfolio management (PPM), particularly with regard to new product development (NPD). There are several life-cycle models in each industry to consider, but most are rather similar. What follows below is one possible life-cycle model; while it emphasizes hardware-oriented products, similar phases would describe any form of product or service, including non-technical or software-based products:

Phase 1: Conceive

Imagine, specify, plan, innovate

The first stage is the definition of the product requirements based on customer, company, market, and regulatory bodies' viewpoints. From this specification, the product's major technical parameters can be defined. In parallel, the initial concept design work is performed defining the aesthetics of the product together with its main functional aspects. Many different media are used for these processes, from pencil and paper to clay models to 3D CAID computer-aided industrial design software.

In some concepts, the investment of resources into research or analysis-of-options may be included in the conception phase – e.g. bringing the technology to a level of maturity sufficient to move to the next phase. However, life-cycle engineering is iterative. It is always possible that something does not work well in any phase enough to back up into a prior phase – perhaps all the way back to conception or research. There are many examples to draw from.

The new product development process phase collects and evaluates both market and technical risks by measuring KPI and scoring model.

Phase 2: Design

Describe, define, develop, test, analyze and validate

This is where the detailed design and development of the product's form starts, progressing to prototype testing, from pilot release to full product launch. It can also involve redesign and ramp for improvement to existing products as well as planned obsolescence. The main tool used for design and development is CAD. This can be simple 2D drawing/drafting or 3D parametric feature-based solid/surface modeling. Such software includes technology such as Hybrid Modeling, Reverse Engineering, KBE (knowledge-based engineering), NDT (Nondestructive testing), and Assembly construction.

This step covers many engineering disciplines including mechanical, electrical, electronic, software (embedded), and domain-specific, such as architectural, aerospace, automotive, … Along with the actual creation of geometry, there is the analysis of the components and product assemblies. Simulation, validation, and optimization tasks are carried out using CAE (computer-aided engineering) software either integrated into the CAD package or stand-alone. These are used to perform tasks such as Stress analysis, FEA (finite element analysis); kinematics; computational fluid dynamics (CFD); and mechanical event simulation (MES). CAQ (computer-aided quality) is used for tasks such as Dimensional tolerance (engineering) analysis. Another task performed at this stage is the sourcing of bought-out components, possibly with the aid of procurement systems.

Phase 3: Realize

Manufacture, make, build, procure, produce, sell and deliver

Once the design of the product's components is complete, the method of manufacturing is defined. This includes CAD tasks such as tool design; including the creation of CNC machining instructions for the product's parts as well as the creation of specific tools to manufacture those parts, using integrated or separate CAM (computer-aided manufacturing) software. This will also involve analysis tools for process simulation of operations such as casting, molding, and die-press forming.

Once the manufacturing method has been identified, CPM comes into play. This involves CAPE (computer-aided production engineering) or CAP/CAPP (computer-aided production planning) tools for carrying out factory, plant and facility layout, and production simulation e.g. press-line simulation, industrial ergonomics, as well as tool selection management.

After components are manufactured, their geometrical form and size can be checked against the original CAD data with the use of computer-aided inspection equipment and software. Parallel to the engineering tasks, sales product configuration, and marketing documentation work takes place. This could include transferring engineering data (geometry and part list data) to a web-based sales configurator and other desktop publishing systems.

Phase 4: Service

Use, operate, maintain, support, sustain, phase-out, retire, recycle and disposal

Another phase of the lifecycle involves managing "in-service" information. This can include providing customers and service engineers with the support and information required for repair and maintenance, as well as waste management or recycling. This can involve the use of tools such as Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul Management (MRO) software.

An effective service consideration begins during and even prior to product design as an integral part of product lifecycle management. Service Lifecycle Management (SLM) has critical touchpoints at all phases of the product lifecycle that must be considered. Connecting and enriching a common digital thread will provide enhanced visibility across functions, improve data quality, and minimize costly delays and rework.

There is an end-of-life to every product. Whether it be the disposal or destruction of material objects or information, this needs to be carefully considered since it may be legislated and hence not free from ramifications.

Operational upgrades

During the operational phase, a product owner may discover components and consumables which have reached their individual end of life and for which there are Diminishing Manufacturing Sources or Material Shortages (DMSMS), or that the existing product can be enhanced for a wider or emerging user market easier or at less cost than a full redesign. This modernization approach often extends the product lifecycle and delays end-of-life disposal.

All phases: product lifecycle

Communicate, manage and collaborate

None of the above phases should be considered as isolated. In reality, a project does not run sequentially or separated from other product development projects, with information flowing between different people and systems. A major part of PLM is the coordination and management of product definition data. This includes managing engineering changes and release status of components; configuration product variations; document management; planning project resources as well as timescale and risk assessment.

For these tasks data of a graphical, textual, and meta nature – such as product bills of materials (BOMs) – needs to be managed. At the engineering departments level, this is the domain of Product Data Management (PDM) software, or at the corporate level Enterprise Data Management (EDM) software; such rigid level distinctions may not be consistently used, however, it is typical to see two or more data management systems within an organization. These systems may also be linked to other corporate systems such as SCM, CRM, and ERP. Associated with these systems are project management systems for project/program planning.

This central role is covered by numerous collaborative product development tools that run throughout the whole lifecycle and across organizations. This requires many technology tools in the areas of conferencing, data sharing, and data translation. This specialized field is referred to as product visualization which includes technologies such as DMU (digital mock-up), immersive virtual digital prototyping (virtual reality), and photo-realistic imaging.

User skills

The broad array of solutions that make up the tools used within a PLM solution-set (e.g., CAD, CAM, CAx...) were initially used by dedicated practitioners who invested time and effort to gain the required skills. Designers and engineers produced excellent results with CAD systems, manufacturing engineers became highly skilled CAM users, while analysts, administrators, and managers fully mastered their support technologies. However, achieving the full advantages of PLM requires the participation of many people of various skills from throughout an extended enterprise, each requiring the ability to access and operate on the inputs and output of other participants.

Despite the increased ease of use of PLM tools, cross-training all personnel on the entire PLM tool-set has not proven to be practical. Now, however, advances are being made to address ease of use for all participants within the PLM arena. One such advance is the availability of "role" specific user interfaces. Through tailorable user interfaces (UIs), the commands that are presented to users are appropriate to their function and expertise.

These techniques include:

- Concurrent engineering workflow

- Industrial design

- Bottom–up design

- Top–down design

- Both-ends-against-the-middle design

- Front-loading design workflow

- Design in context

- Modular design

- NPD new product development

- DFSS design for Six Sigma

- DFMA design for manufacture / assembly

- Digital simulation engineering

- Requirement-driven design

- Specification-managed validation

- Configuration management

Concurrent engineering workflow

Concurrent engineering (British English: simultaneous engineering) is a workflow that, instead of working sequentially through stages, carries out a number of tasks in parallel. For example: starting tool design as soon as the detailed design has started, and before the detailed designs of the product are finished; or starting on detailed design solid models before the concept design surfaces models are complete. Although this does not necessarily reduce the amount of manpower required for a project, as more changes are required due to incomplete and changing information, it does drastically reduce lead times and thus time to market.

Feature-based CAD systems have allowed simultaneous work on the 3D solid model and the 2D drawing by means of two separate files, with the drawing looking at the data in the model; when the model changes the drawing will associatively update. Some CAD packages also allow associative copying of geometry between files. This allows, for example, the copying of a part design into the files used by the tooling designer. The manufacturing engineer can then start work on tools before the final design freeze; when a design changes size or shape the tool geometry will then update.

Concurrent engineering also has the added benefit of providing better and more immediate communication between departments, reducing the chance of costly, late design changes. It adopts a problem-prevention method as compared to the problem-solving and re-designing method of traditional sequential engineering.

Bottom–up design

Bottom–up design (CAD-centric) occurs where the definition of 3D models of a product starts with the construction of individual components. These are then virtually brought together in sub-assemblies of more than one level until the full product is digitally defined. This is sometimes known as the "review structure" which shows what the product will look like. The BOM contains all of the physical (solid) components of a product from a CAD system; it may also (but not always) contain other 'bulk items' required for the final product but which (in spite of having definite physical mass and volume) are not usually associated with CAD geometry such as paint, glue, oil, adhesive tape, and other materials.

Bottom–up design tends to focus on the capabilities of available real-world physical technology, implementing those solutions to which this technology is most suited. When these bottom–up solutions have real-world value, bottom–up design can be much more efficient than top–down design. The risk of bottom–up design is that it very efficiently provides solutions to low-value problems. The focus of bottom–up design is "what can we most efficiently do with this technology?" rather than the focus of top–down which is "What is the most valuable thing to do?"

Top–down design

Top–down design is focused on high-level functional requirements, with relatively less focus on existing implementation technology. A top-level spec is repeatedly decomposed into lower-level structures and specifications until the physical implementation layer is reached. The risk of a top–down design is that it may not take advantage of more efficient applications of current physical technology, due to excessive layers of lower-level abstraction due to following an abstraction path that does not efficiently fit available components e.g. separately specifying sensing, processing, and wireless communications elements even though a suitable component that combines these may be available. The positive value of top–down design is that it preserves a focus on the optimum solution requirements.

A part-centric top–down design may eliminate some of the risks of top–down design. This starts with a layout model, often a simple 2D sketch defining basic sizes and some major defining parameters, which may include some Industrial design elements. Geometry from this is associatively copied down to the next level, which represents different subsystems of the product. The geometry in the sub-systems is then used to define more detail in the levels below. Depending on the complexity of the product, a number of levels of this assembly are created until the basic definition of components can be identified, such as position and principal dimensions. This information is then associatively copied to component files. In these files the components are detailed; this is where the classic bottom–up assembly starts.

The top–down assembly is sometimes known as a "control structure". If a single file is used to define the layout and parameters for the review structure it is often known as a skeleton file.

Defense engineering traditionally develops the product structure from the top down. The system engineering process prescribes a functional decomposition of requirements and then the physical allocation of product structure to the functions. This top down approach would normally have lower levels of the product structure developed from CAD data as a bottom–up structure or design.

Both-ends-against-the-middle design

Both-ends-against-the-middle (BEATM) design is a design process that endeavors to combine the best features of top–down design, and bottom–up design into one process. A BEATM design process flow may begin with an emergent technology that suggests solutions that may have value, or it may begin with a top–down view of an important problem that needs a solution. In either case, the key attribute of BEATM design methodology is to immediately focus on both ends of the design process flow: a top–down view of the solution requirements, and a bottom–up view of the available technology which may offer the promise of an efficient solution. The BEATM design process proceeds from both ends in search of an optimum merging somewhere between the top–down requirements, and bottom–up efficient implementation. In this fashion, BEATM has been shown to genuinely offer the best of both methodologies. Indeed, some of the best success stories from either top–down or bottom–up have been successful because of an intuitive, yet unconscious use of the BEATM methodology. When employed consciously, BEATM offers even more powerful advantages.

Front loading design and workflow

Front loading is taking top–down design to the next stage. The complete control structure and review structure, as well as downstream data such as drawings, tooling development, and CAM models, are constructed before the product has been defined or a project kick-off has been authorized. These assemblies of files constitute a template from which a family of products can be constructed. When the decision has been made to go with a new product, the parameters of the product are entered into the template model, and all the associated data is updated. Obviously, predefined associative models will not be able to predict all possibilities and will require additional work. The main principle is that a lot of the experimental/investigative work has already been completed. A lot of knowledge is built into these templates to be reused on new products. This does require additional resources "up front" but can drastically reduce the time between project kick-off and launch. Such methods do however require organizational changes, as considerable engineering efforts are moved into "offline" development departments. It can be seen as an analogy to creating a concept car to test new technology for future products, but in this case, the work is directly used for the next product generation.

Design in context

Individual components cannot be constructed in isolation. CAD and CAID models of components are created within the context of some or all of the other components within the product being developed. This is achieved using assembly modelling techniques. The geometry of other components can be seen and referenced within the CAD tool being used. The other referenced components may or may not have been created using the same CAD tool, with their geometry being translated from other collaborative product development (CPD) formats. Some assembly checking such as DMU is also carried out using product visualization software.

Product and process lifecycle management (PPLM)

Product and process lifecycle management (PPLM) is an alternate genre of PLM in which the process by which the product is made is just as important as the product itself. Typically, this is the life sciences and advanced specialty chemicals markets. The process behind the manufacture of a given compound is a key element of the regulatory filing for a new drug application. As such, PPLM seeks to manage information around the development of the process in a similar fashion that baseline PLM talks about managing information around the development of the product.

One variant of PPLM implementations are Process Development Execution Systems (PDES). They typically implement the whole development cycle of high-tech manufacturing technology developments, from initial conception, through development, and into manufacture. PDES integrates people with different backgrounds from potentially different legal entities, data, information and knowledge, and business processes.

Market size

After the Great Recession, PLM investments from 2010 onwards showed a higher growth rate than most general IT spending.

Total spending on PLM software and services was estimated in 2020 to be $26 billion a year, with an estimated compound annual growth rate of 7.2% from 2021 to 2028. This was expected to be driven by a demand for software solutions for management functions, such as change, cost, compliance, data, and governance management.

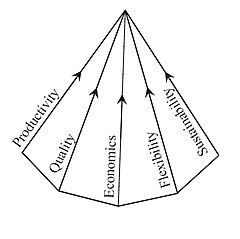

Pyramid of production systems

According to Malakooti (2013), there are five long-term objectives that should be considered in production systems:

- Cost: Which can be measured in terms of monetary units and usually consists of fixed and variable costs.

- Productivity: Which can be measured in terms of the number of products produced during a period of time.

- Quality: Which can be measured in terms of customer satisfaction levels for example.

- Flexibility: Which can be considered the ability of the system to produce a variety of products for example.

- Sustainability: Which can be measured in terms of ecological soundness i.e. biological and environmental impacts of a production system.

The relation between these five objects can be presented as a pyramid with its tip associated with the lowest Cost, highest Productivity, highest Quality, most Flexibility, and greatest Sustainability. The points inside of this pyramid are associated with different combinations of five criteria. The tip of the pyramid represents an ideal (but likely highly unfeasible) system whereas the base of the pyramid represents the worst system possible.

See also

- Application lifecycle management

- Building lifecycle management

- Cradle-to-cradle design

- Durable good

- Hype cycle

- ISO 10303 – Standard for the Exchange of Product model data

- Kondratiev wave

- Life cycle thinking

- Life-cycle assessment

- Product data record

- Product management

- Sustainable materials management

- System lifecycle

- Technology roadmap

- User-centered design

References

- Kurkin, Ondřej; Januška, Marlin (2010). "Product Life Cycle in Digital factory". Knowledge Management and Innovation: A Business Competitive Edge Perspective. Cairo: International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA): 1881–1886. ISBN 9780982148945.

- "About PLM". CIMdata. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "What is PLM?". PLM Technology Guide. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Cunha, Luciano (20 July 2010). "Manufacturing Pioneers Reduce Costs By Integrating PLM & ERP". onwindows.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Wong, Kenneth (29 July 2009). "What PLM Can Learn from Social Media". Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ Hill, Jr., Sidney (May 2003). "How To Be A Trendsetter: Dassault and IBM PLM Customers Swap Tales From The PLM Front". COE newsnet. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- Pearce, John A.; Robinson, Richard B. (1991). Formulation, implementation, and control of competitive strategy (4 ed.). Irwin. p. 315. ISBN 9780256083248. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- Karniel, Arie; Reich, Yoram (2011). Managing the Dynamic of New Product Development Processes. A new Product Lifecycle Management Paradigm. Springer. p. 13. ISBN 9780857295699. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Evans, Mike (April 2001). "The PLM Debate" (PDF). Cambashi. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- Day, Martyn (15 April 2002). "What is PLM". Cad Digest. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Hill, Sidney (September 2006). "A winning strategy" (PDF). Manufacturing Business Technology. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Kopei, Volodymyr; Onysko, Oleh; Barz, Cristian; Dašić, Predrag; Panchuk, Vitalii (February 2023). "Designing a Multi-Agent PLM System for Threaded Connections Using the Principle of Isomorphism of Regularities of Complex Systems". Machines. 11 (2): 263. doi:10.3390/machines11020263.

- Teresko, John (21 December 2004). "The PLM Revolution". IndustryWeek. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- Stackpole, Beth (11 June 2003). "There's a New App in Town". CIO Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Gould, Lawrence (12 January 2005). "Additional ABCs About PLM". Automotive Design and Production. Archived from the original on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Product Life Cycle". Buy Strategy. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- Cooper, Tim, ed. (2010). Longer Lasting Products: Alternatives to the Throwaway Society. Farnham, UK: Gower. ISBN 9780566088087.

- CE is so defined by the PACE consortium (Walker, 1997)

- Incose Systems Engineering Handbook, Version 2.0. July 2000. p. 358. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- "PLM Spending: A period of "Digestion" after two years of explosive growth". engineering.com. 27 August 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ "Product Lifecycle Management Market Size Report 2021-2028". grandviewresearch.com. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- Malakooti, Behnam (2013). Operations and Production Systems with Multiple Objectives. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118585375.

Further reading

- Bergsjö, Dag (2009). Product Lifecycle Management – Architectural and Organisational Perspectives (PDF). Chalmers University of Technology. ISBN 9789173852579.

- Grieves, Michael (2005). Product Lifecycle Management: Driving the Next Generation of Lean Thinking. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071452304.

- Saaksvuori, Antti (2008). Product Lifecycle Management. Springer. ISBN 9783540781738.

External links

Media related to Product lifecycle management at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Product lifecycle management at Wikimedia Commons

| Management | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By type of organization |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| By focus, within an organization |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Positions | |||||||||||||||||||

| Methods, approaches | |||||||||||||||||||

| Skills, activities | |||||||||||||||||||

| Pioneers, scholars | |||||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||

| Degrees | |||||||||||||||||||

| Other |

| ||||||||||||||||||