Business process re-engineering (BPR) is a business management strategy originally pioneered in the early 1990s, focusing on the analysis and design of workflows and business processes within an organization. BPR aims to help organizations fundamentally rethink how they do their work in order to improve customer service, cut operational costs, and become world-class competitors.

BPR seeks to help companies radically restructure their organizations by focusing on the ground-up design of their business processes. According to early BPR proponent Thomas H. Davenport (1990), a business process is a set of logically related tasks performed to achieve a defined business outcome. Re-engineering emphasized a holistic focus on business objectives and how processes related to them, encouraging full-scale recreation of processes, rather than iterative optimization of sub-processes. BPR is influenced by technological innovations as industry players replace old methods of business operations with cost-saving innovative technologies such as automation that can radically transform business operations.

Business process re-engineering is also known as business process redesign, business transformation, or business process change management.

Overview

Business process re-engineering (BPR) is a comprehensive approach to redesigning and optimizing organizational processes to improve efficiency, effectiveness, and adaptability. This method of organizational transformation is implemented by analyzing and restructuring various aspects of a business, such as workflow, communication, and decision-making processes, with the goal of achieving significant improvements in performance, such as increased productivity, reduced costs, and improved customer satisfaction. BPR is a powerful tool that can be applied to various industries and organizations of all sizes, and it can be achieved through various methodologies and techniques, such as process mapping, process simulation, and process automation. Organizations re-engineer two key areas of their businesses. First, they use modern technology to enhance data dissemination and decision-making processes. Then, they alter functional organizations to form functional teams. Re-engineering starts with a high-level assessment of the organization's mission, strategic goals, and customer needs. Basic questions are asked, such as "Does our mission need to be redefined? Are our strategic goals aligned with our mission? Who are our customers?" An organization may find that it is operating on questionable assumptions, particularly in terms of the wants and needs of its customers. Only after the organization rethinks what it should be doing, does it go on to decide how to best do it.

Within the framework of this basic assessment of mission and goals, re-engineering focuses on the organization's business processes—the steps and procedures that govern how resources are used to create products and services that meet the needs of particular customers or markets. As a structured ordering of work steps across time and place, a business process can be decomposed into specific activities, measured, modeled, and improved. It can also be completely redesigned or eliminated altogether. Re-engineering identifies, analyzes, and re-designs an organization's core business processes with the aim of achieving improvements in critical performance measures, such as cost, quality, service, and speed.

Re-engineering recognizes that an organization's business processes are usually fragmented into sub-processes and tasks that are carried out by several specialized functional areas within the organization. Often, no one is responsible for the overall performance of the entire process. Re-engineering maintains that optimizing the performance of sub-processes can result in some benefits but cannot yield improvements if the process itself is fundamentally inefficient and outmoded. For that reason, re-engineering focuses on re-designing the process as a whole in order to achieve the greatest possible benefits to the organization and their customers. This drive for realizing improvements by fundamentally re-thinking how the organization's work should be done distinguishes the re-engineering from process improvement efforts that focus on functional or incremental improvement.

History

BPR began as a private sector technique to help organizations rethink how they do their work in order to improve customer service, cut operational costs, and become world-class competitors. A key stimulus for re-engineering has been the continuing development and deployment of information systems and networks. Organizations are becoming bolder in using this technology to support business processes, rather than refining current ways of doing work.

Reengineering Work: Don't Automate, Obliterate, 1990

In 1990, Michael Hammer, a former professor of computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), published the article "Reengineering Work: Don't Automate, Obliterate" in the Harvard Business Review, in which he claimed that the major challenge for managers is to obliterate forms of work that do not add value, rather than using technology for automating it. This statement implicitly accused managers of having focused on the wrong issues, namely that technology in general, and more specifically information technology, has been used primarily for automating existing processes rather than using it as an enabler for making non-value adding work obsolete.

Hammer's claim was simple: Most of the work being done does not add any value for customers, and this work should be removed, not accelerated through automation. Instead, companies should reconsider their inability to satisfy customer needs, and their insufficient cost structure. Even well-established management thinkers, such as Peter Drucker and Tom Peters, were accepting and advocating BPR as a new tool for (re-)achieving success in a dynamic world. During the following years, a fast-growing number of publications, books as well as journal articles, were dedicated to BPR, and many consulting firms embarked on this trend and developed BPR methods. However, the critics were fast to claim that BPR was a way to dehumanize the work place, increase managerial control, and to justify downsizing, i.e. major reductions of the work force, and a rebirth of Taylorism under a different label.

Despite this critique, re-engineering was adopted at an accelerating pace and by 1993, as many as 60% of the Fortune 500 companies claimed to either have initiated re-engineering efforts, or to have plans to do so. This trend was fueled by the fast adoption of BPR by the consulting industry, but also by the study Made in America, conducted by MIT, that showed how companies in many US industries had lagged behind their foreign counterparts in terms of competitiveness, time-to-market and productivity.

Development after 1995

With the publication of critiques in 1995 and 1996 by some of the early BPR proponents, coupled with abuses and misuses of the concept by others, the re-engineering fervor in the U.S. began to wane. Since then, considering business processes as a starting point for business analysis and redesign has become a widely accepted approach and is a standard part of the change methodology portfolio, but is typically performed in a less radical way than originally proposed.

More recently, the concept of Business Process Management (BPM) has gained major attention in the corporate world and can be considered a successor to the BPR wave of the 1990s, as it is evenly driven by a striving for process efficiency supported by information technology. Equivalently to the critique brought forward against BPR, BPM is now accused of focusing on technology and disregarding the people aspects of change.

Topics

The most notable definitions of reengineering are:

- "... the fundamental rethinking and radical redesign of business processes to achieve ... improvements in critical contemporary modern measures of performance, such as cost, quality, service, and speed."

- "encompasses the envisioning of new work strategies, the actual process design activity, and the implementation of the change in all its complex technological, human, and organizational dimensions."

BPR is different from other approaches to organization development (OD), especially the continuous improvement or TQM movement, by virtue of its aim for fundamental and radical change rather than iterative improvement. In order to achieve the major improvements BPR is seeking for, the change of structural organizational variables, and other ways of managing and performing work is often considered insufficient. For being able to reap the achievable benefits fully, the use of information technology (IT) is conceived as a major contributing factor. While IT traditionally has been used for supporting the existing business functions, i.e. it was used for increasing organizational efficiency, it now plays a role as enabler of new organizational forms, and patterns of collaboration within and between organizations.

BPR derives its existence from different disciplines, and four major areas can be identified as being subjected to change in BPR – organization, technology, strategy, and people – where a process view is used as common framework for considering these dimensions.

Business strategy is the primary driver of BPR initiatives and the other dimensions are governed by strategy's encompassing role. The organization dimension reflects the structural elements of the company, such as hierarchical levels, the composition of organizational units, and the distribution of work between them. Technology is concerned with the use of computer systems and other forms of communication technology in the business. In BPR, information technology is generally considered to act as enabler of new forms of organizing and collaborating, rather than supporting existing business functions. The people / human resources dimension deals with aspects such as education, training, motivation and reward systems. The concept of business processes – interrelated activities aiming at creating a value added output to a customer – is the basic underlying idea of BPR. These processes are characterized by a number of attributes: Process ownership, customer focus, value adding, and cross-functionality.

The role of information technology

Information technology (IT) has historically played an important role in the reengineering concept. It is regarded by some as a major enabler for new forms of working and collaborating within an organization and across organizational borders.

BPR literature identified several so called disruptive technologies that were supposed to challenge traditional wisdom about how work should be performed.

- Shared databases, making information available at many places

- Expert systems, allowing generalists to perform specialist tasks

- Telecommunication networks, allowing organizations to be centralized and decentralized at the same time

- Decision-support tools, allowing decision-making to be a part of everybody's job

- Wireless data communication and portable computers, allowing field personnel to work office independent

- Interactive videodisk, to get in immediate contact with potential buyers

- Automatic identification and tracking, allowing things to tell where they are, instead of requiring to be found

- High performance computing, allowing on-the-fly planning and revisioning

In the mid-1990s especially, workflow management systems were considered a significant contributor to improved process efficiency. Also, ERP (enterprise resource planning) vendors, such as SAP, JD Edwards, Oracle, and PeopleSoft, positioned their solutions as vehicles for business process redesign and improvement.

Research and methodology

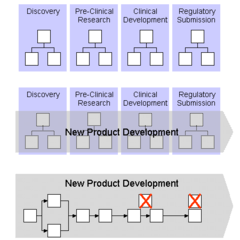

Although the labels and steps differ slightly, the early methodologies that were rooted in IT-centric BPR solutions share many of the same basic principles and elements. The following outline is one such model, based on the Process Reengineering Life Cycle (PRLC) approach developed by Guha. Simplified schematic outline of using a business process approach, exemplified for pharmaceutical R&D

- Structural organization with functional units

- Introduction of New Product Development as cross-functional process

- Re-structuring and streamlining activities, removal of non-value adding tasks

Benefiting from lessons learned from the early adopters, some BPR practitioners advocated a change in emphasis to a customer-centric, as opposed to an IT-centric, methodology. One such methodology, that also incorporated a Risk and Impact Assessment to account for the effect that BPR can have on jobs and operations, was described by Lon Roberts (1994). Roberts also stressed the use of change management tools to proactively address resistance to change a factor linked to the demise of many reengineering initiatives that looked good on the drawing board.

Some items to use on a process analysis checklist are: Reduce handoffs, Centralize data, Reduce delays, Free resources faster, Combine similar activities. Also within the management consulting industry, a significant number of methodological approaches have been developed.

Framework

An easy to follow seven step INSPIRE framework is developed by Bhudeb Chakravarti which can be followed by any Process Analyst to perform BPR. The seven steps of the framework are Initiate a new process reengineering project and prepare a business case for the same; Negotiate with senior management to get approval to start the process reengineering project; Select the key processes that need to be reengineered; Plan the process reengineering activities; Investigate the processes to analyze the problem areas; Redesign the selected processes to improve the performance and Ensure the successful implementation of redesigned processes through proper monitoring and evaluation.

Factors for success and failure

| This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Misplaced Pages. See Misplaced Pages's guide to writing better articles for suggestions. (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Factors that are important to BPR success include:

- BPR team composition.

- Business needs analysis.

- Adequate IT infrastructure.

- Effective change management.

- Ongoing continuous improvement.

The aspects of a BPM effort that are modified include organizational structures, management systems, employee responsibilities, and performance measurements, incentive systems, skills development, and the use of IT. BPR can potentially affect every aspect of how business is conducted today. Wholesale changes can cause results ranging from enviable success to complete failure.

If successful, a BPM initiative can result in improved quality, customer service, and competitiveness, as well as reductions in cost or cycle time. However, 50-70% of reengineering projects are either failures or do not achieve significant benefit.

There are many reasons for sub-optimal business processes which include:

- One department may be optimized at the expense of another

- Lack of time to focus on improving business process

- Lack of recognition of the extent of the problem

- Lack of training

- People involved use the best tool they have at their disposal which is usually Excel to fix problems

- Inadequate infrastructure

- Overly bureaucratic processes

- Lack of motivation

Many unsuccessful BPR attempts may have been due to the confusion surrounding BPR, and how it should be performed. Organizations were well aware that changes needed to be made but did not know which areas to change or how to change them. As a result, process reengineering is a management concept that has been formed by trial and error or, in other words, practical experience. As more and more businesses reengineer their processes, knowledge of what caused the successes or failures is becoming apparent. To reap lasting benefits, companies must be willing to examine how strategy and reengineering complement each other by learning to quantify strategy in terms of cost, milestones, and timetables, by accepting ownership of the strategy throughout the organization, by assessing the organization's current capabilities and process realistically, and by linking strategy to the budgeting process. Otherwise, BPR is only a short-term efficiency exercise.

Organization-wide commitment

Major changes to business processes have a direct effect on processes, technology, job roles, and workplace culture. Significant changes to even one of those areas require resources, money, and leadership. Changing them simultaneously is an extraordinary task. Like any large and complex undertaking, implementing re engineering requires the talents and energies of a broad spectrum of experts. Since BPR can involve multiple areas within the organization, it is important to get support from all affected departments. Through the involvement of selected department members, the organization can gain valuable input before a process is implemented; a step that promotes both the cooperation and the vital acceptance of the re engineered process by all segments of the organization.

Getting enterprise-wide commitment involves the following: top management sponsorship, bottom-up buy-in from process users, dedicated BPR team, and budget allocation for the total solution with measures to demonstrate value. Before any BPR project can be implemented successfully, there must be a commitment to the project by the management of the organization, and strong leadership must be provided. Re engineering efforts can by no means be exercised without a company-wide commitment to the goals. However, top management commitment is imperative for success. Top management must recognize the need for change, develop a complete understanding of what BPR is, and plan how to achieve it.

Leadership has to be effective, strong, visible, and creative in thinking and understanding in order to provide a clear vision. Convincing every affected group within the organization of the need for BPR is a key step in successfully implementing a process. By informing all affected groups at every stage, and emphasizing the positive end results of the re engineering process, it is possible to minimize resistance to change and increase the odds for success. The ultimate success of BPR depends on the strong, consistent, and continuous involvement of all departmental levels within the organization.

Team composition

Once an organization-wide commitment has been secured from all departments involved in the re engineering effort and at different levels, the critical step of selecting a BPR team must be taken. This team will form the nucleus of the BPR effort, make key decisions and recommendations, and help communicate the details and benefits of the BPR program to the entire organization. The determinants of an effective BPR team may be summarized as follows:

- competency of the members of the team, their motivation,

- their credibility within the organization and their creativity,

- team empowerment, training of members in process mapping and brainstorming techniques,

- effective team leadership,

- proper organization of the team,

- complementary skills among team members, adequate size, interchangeable accountability, clarity of work approach, and

- specificity of goals.

The most effective BPR teams include active representatives from the following work groups: top management, the business area responsible for the process being addressed, technology groups, finance, and members of all ultimate process users' groups. Team members who are selected from each work group within the organization will affect the outcome of the re engineered process according to their desired requirements. The BPR team should be mixed in-depth and knowledge. For example, it may include members with the following characteristics:

- Members who do not know the process at all.

- Members who know the process inside-out.

- Customers, if possible.

- Members representing affected departments.

- One or two members of the best, brightest, passionate, and committed technology experts.

- Members from outside of the organization.

Moreover, Covert (1997) recommends that in order to have an effective BPR team, it must be kept under ten players. If the organization fails to keep the team at a manageable size, the entire process will be much more difficult to execute efficiently and effectively. The efforts of the team must be focused on identifying breakthrough opportunities and designing new work steps or processes that will create quantum gains and competitive advantage.

Business needs analysis

Another important factor in the success of any BPR effort is performing a thorough business needs analysis. Too often, BPR teams jump directly into the technology without first assessing the current processes of the organization and determining what exactly needs re engineering. In this analysis phase, a series of sessions should be held with process owners and stakeholders, regarding the need and strategy for BPR. These sessions build a consensus as to the vision of the ideal business process. They help identify essential goals for BPR within each department and then collectively define objectives for how the project will affect each work group or department on an individual basis and the business organization as a whole. The idea of these sessions is to conceptualize the ideal business process for the organization and build a business process model. Those items that seem unnecessary or unrealistic may be eliminated or modified later on in the diagnosing stage of the BPR project. It is important to acknowledge and evaluate all ideas in order to make all participants feel that they are a part of this important and crucial process. The results of these meetings will help formulate the basic plan for the project.

This plan includes the following:

- identifying specific problem areas,

- solidifying particular goals, and

- defining business objectives.

The business needs analysis contributes tremendously to the re-engineering effort by helping the BPR team to prioritize and determine where it should focus its improvements efforts.

The business needs analysis also helps in relating the BPR project goals back to key business objectives and the overall strategic direction for the organization. This linkage should show the thread from the top to the bottom of the organization, so each person can easily connect the overall business direction with the re-engineering effort. This alignment must be demonstrated from the perspective of financial performance, customer service, associate value, and the vision for the organization. Developing a business vision and process objectives rely, on the one hand, on a clear understanding of organizational strengths, weaknesses, and market structure, and on the other, on awareness and knowledge about innovative activities undertaken by competitors and other organizations.

BPR projects that are not in alignment with the organization's strategic direction can be counterproductive. There is always a possibility that an organization may make significant investments in an area that is not a core competency for the company and later outsource this capability. Such re engineering initiatives are wasteful and steal resources from other strategic projects. Moreover, without strategic alignment, the organization's key stakeholders and sponsors may find themselves unable to provide the level of support the organization needs in terms of resources, especially if there are other more critical projects to the future of the business, and are more aligned with the strategic direction.

Adequate IT infrastructure

Researchers consider adequate IT infrastructure reassessment and composition as a vital factor in successful BPR implementation. Hammer (1990) prescribes the use of IT to challenge the assumptions inherent in the work process that have existed since long before the advent of modern computer and communications technology. Factors related to IT infrastructure have been increasingly considered by many researchers and practitioners as a vital component of successful BPR efforts.

- Effective alignment of IT infrastructure and BPR strategy,

- Building an effective IT infrastructure,

- adequate IT infrastructure investment decision,

- adequate measurement of IT infrastructure effectiveness,

- proper information systems (IS) integration,

- effective re engineering of legacy IS,

- increasing IT function competency, and

- effective use of software tools is the most important factor that contributes to the success of BPR projects.

These are vital factors that contribute to building an effective IT infrastructure for business processes. BPR must be accompanied by strategic planning which addresses leveraging IT as a competitive tool. An IT infrastructure is made up of physical assets, intellectual assets, shared services, and their linkages. The way in which the IT infrastructure components are composed and their linkages determine the extent to which information resources can be delivered. An effective IT infrastructure composition process follows a top-down approach, beginning with business strategy and IS strategy and passing through designs of data, systems, and computer architecture.

Linkages between the IT infrastructure components, as well as descriptions of their contexts of interaction, are important for ensuring integrity and consistency among the IT infrastructure components. Furthermore, IT standards have a major role in reconciling various infrastructure components to provide shared IT services that are of a certain degree of effectiveness to support business process applications, as well as to guide the process of acquiring, managing, and utilizing IT assets. The IT infrastructure shared services and the human IT infrastructure components, in terms of their responsibilities and their needed expertise, are both vital to the process of the IT infrastructure composition. IT strategic alignment is approached through the process of integration between business and IT strategies, as well as between IT and organizational infrastructures.

Most analysts view BPR and IT as irrevocably linked. Walmart, for example, would not have been able to reengineer the processes used to procure and distribute mass-market retail goods without IT. Ford was able to decrease its headcount in the procurement department by 75 percent by using IT in conjunction with BPR, in another well-known example. The IT infrastructure and BPR are interdependent in the sense that deciding the information requirements for the new business processes determines the IT infrastructure constituents, and a recognition of IT capabilities provides alternatives for BPR. Building a responsive IT infrastructure is highly dependent on an appropriate determination of business process information needs. This, in turn, is determined by the types of activities embedded in a business process, and their sequencing and reliance on other organizational processes.

Effective change management

Al-Mashari and Zairi (2000) suggest that BPR involves changes in people's behavior and culture, processes, and technology. As a result, there are many factors that prevent the effective implementation of BPR and hence restrict innovation and continuous improvement. Change management, which involves all human and social related changes and cultural adjustment techniques needed by management to facilitate the insertion of newly designed processes and structures into working practice and to deal effectively with resistance, is considered by many researchers to be a crucial component of any BPR effort. One of the most overlooked obstacles to successful BPR project implementation is resistance from those whom implementer believe will benefit the most. Most projects underestimate the cultural effect of major process and structural change and as a result, do not achieve the full potential of their change effort. Many people fail to understand that change is not an event, but rather a management technique.

Change management is the discipline of managing change as a process, with due consideration that employees are people, not programmable machines. Change is implicitly driven by motivation which is fueled by the recognition of the need for change. An important step towards any successful reengineering effort is to convey an understanding of the necessity for change. It is a well-known fact that organizations do not change unless people change; the better the change is managed, the less painful the transition is.

Organizational culture is a determining factor in successful BPR implementation. Organizational culture influences the organization's ability to adapt to change. Culture in an organization is a self-reinforcing set of beliefs, attitudes, and behavior. Culture is one of the most resistant elements of organizational behavior and is extremely difficult to change. BPR must consider current culture in order to change these beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors effectively. Messages conveyed from management in an organization continually enforce current culture. Change is implicitly driven by motivation which is fueled by the recognition of the need for change.

The first step towards any successful transformation effort is to convey an understanding of the necessity for change. Management rewards system, stories of company origin and early successes of founders, physical symbols, and company icons constantly enforce the message of the current culture. Implementing BPR successfully is dependent on how thoroughly management conveys the new cultural messages to the organization. These messages provide people in the organization with a guideline to predict the outcome of acceptable behavior patterns. People should be the focus of any successful business change.

BPR is not a recipe for successful business transformation if it focuses on only computer technology and process redesign. In fact, many BPR projects have failed because they did not recognize the importance of the human element in implementing BPR. Understanding the people in organizations, the current company culture, motivation, leadership, and past performance is essential to recognize, understand, and integrate into the vision and implementation of BPR. If the human element is given equal or greater emphasis in BPR, the odds of successful business transformation increase substantially.

Ongoing continuous improvement

Many organizational change theorists hold a common view of organizations adjusting gradually and incrementally and responding locally to individual crises as they arise Common elements are:

- BPR is a successive and ongoing process and should be regarded as an improvement strategy that enables an organization to make the move from a traditional functional orientation to one that aligns with strategic business processes.

- Continuous improvement is defined as the propensity of the organization to pursue incremental and innovative improvements in its processes, products, and services. The incremental change is governed by the knowledge gained from each previous change cycle.

- It is essential that the automation infrastructure of the BPR activity provides for performance measurements in order to support continuous improvements. It will need to efficiently capture appropriate data and allow access to appropriate individuals.

- To ensure that the process generates the desired benefits, it must be tested before it is deployed to the end-users. If it does not perform satisfactorily, more time should be taken to modify the process until it does.

- A fundamental concept for quality practitioners is the use of feedback loops at every step of the process and an environment that encourages constant evaluation of results and individual efforts to improve.

- At the end user's level, there must be a proactive feedback mechanism that provides for and facilitates resolutions of problems and issues. This will also contribute to a continuous risk assessment and evaluation which are needed throughout the implementation process to deal with any risks at their initial state and to ensure the success of the reengineering efforts.

- Anticipating and planning for risk handling is important for dealing effectively with any risk when it first occurs and as early as possible in the BPR process. It is interesting that many of the successful applications of reengineering described by its proponents are in organizations practicing continuous improvement programs.

- Hammer and Champy (1993) use the IBM Credit Corporation as well as Ford and Kodak, as examples of companies that carried out BPR successfully due to the fact that they had long-running continuous improvement programs.

In conclusion, successful BPR can potentially create substantial improvements in the way organizations do business and can actually produce fundamental improvements for business operations. However, in order to achieve that, there are some key success factors that must be taken into consideration when performing BPR.

BPR success factors are a collection of lessons learned from reengineering projects and from these lessons common themes have emerged. In addition, the ultimate success of BPR depends on the people who do it and on how well they can be committed and motivated to be creative and to apply their detailed knowledge to the reengineering initiative. Organizations planning to undertake BPR must take into consideration the success factors of BPR in order to ensure that their reengineering related change efforts are comprehensive, well-implemented, and have a minimum chance of failure. This has been very beneficial in all terms

Critique

Many companies used reengineering as a pretext to downsizing, though this was not the intent of reengineering's proponents; consequently, reengineering earned a reputation for being synonymous with downsizing and layoffs.

In many circumstances, reengineering has not always lived up to its expectations. Some prominent reasons include:

- Reengineering assumes that the factor that limits an organization's performance is the ineffectiveness of its processes (which may or may not be true) and offers no means of validating that assumption.

- Reengineering assumes the need to start the process of performance improvement with a "clean slate," i.e. totally disregard the status quo.

- According to Eliyahu M. Goldratt (and his Theory of Constraints) reengineering does not provide an effective way to focus improvement efforts on the organization's constraint.

Others have claimed that reengineering was a recycled buzzword for commonly-held ideas. Abrahamson (1996) argued that fashionable management terms tend to follow a lifecycle, which for Reengineering peaked between 1993 and 1996 (Ponzi and Koenig 2002). They argue that Reengineering was in fact nothing new (as e.g. when Henry Ford implemented the assembly line in 1908, he was in fact reengineering, radically changing the way of thinking in an organization).

The most frequent critique against BPR concerns the strict focus on efficiency and technology and the disregard of people in the organization that is subjected to a reengineering initiative. Very often, the label BPR was used for major workforce reductions. Thomas Davenport, an early BPR proponent, stated that:

"When I wrote about "business process redesign" in 1990, I explicitly said that using it for cost reduction alone was not a sensible goal. And consultants Michael Hammer and James Champy, the two names most closely associated with reengineering, have insisted all along that layoffs shouldn't be the point. But the fact is, once out of the bottle, the reengineering genie quickly turned ugly."

Hammer similarly admitted that:

"I wasn't smart enough about that. I was reflecting my engineering background and was insufficiently appreciative of the human dimension. I've learned that's critical."

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Business Process Re-engineering Assessment Guide, May 1997 (PDF). United States General Accounting Office.

This article incorporates public domain material from Business Process Re-engineering Assessment Guide, May 1997 (PDF). United States General Accounting Office.

- ^ Business Process Re-engineering Assessment Guide, United States General Accounting Office, May 1997.

- Subramoniam, S., 2008. Commanding the internet era. Industrial Engineer, pp.44-48.

- Michael Hammer, "Reengineering Work: Don't Automate, Obliterate", Harvard Business Review, July, 1990

- Forbes: Reengineering, The Hot New Managing Tool, 23 August 1993

- (Greenbaum 1995, Industry Week 1994)

- Hamscher, Walter: "AI in Business-Process Reengineering" Archived 11 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, AI Magazine Volume 15 Number 4, 1994

- Michael L. Dertouzos, Robert M. Solow and Richard K. Lester (1989) Made in America: Regaining the Productive Edge. MIT press.

- Hammer and Champy (1993)

- Thomas H. Davenport (1993)

- Johansson et al. (1993): "Business Process Reengineering, although a close relative, seeks radical rather than merely continuous improvement. It escalates the efforts of JIT and TQM to make process orientation a strategic tool and a core competence of the organization. BPR concentrates on core business processes, and uses the specific techniques within the JIT and TQM "toolboxes" as enablers, while broadening the process vision."

- Business efficiency: IT can help paint a bigger picture, Financial Times, featuring Ian Manocha, Lynne Munns and Andy Cross

- e.g. Hammer & Champy (1993)

- Guha et al. (1993)

- Lon Roberts (1994) Process reengineering: the key to achieving breakthrough success.

- A set of short papers, outlining and comparing some of them can be found here, followed by some guidelines for companies considering to contract a consultancy for a BPR initiative:

- Overview Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Andersen Consulting (now Accenture) Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Bain & Co. Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Boston Consulting Group Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- McKinsey & Co. Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Comparison Archived 10 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Guidelines for BPR consulting clients Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Garcia-Garcia, Guillermo; Coulthard, Guy; Jagtap, Sandeep; Afy-Shararah, Mohamed; Patsavellas, John; Salonitis, Konstantinos (January 2021). "Business Process Re-Engineering to Digitalise Quality Control Checks for Reducing Physical Waste and Resource Use in a Food Company" (PDF). Sustainability. 13 (22): 12341. doi:10.3390/su132212341. ISSN 2071-1050.

- Asian Productivity Organization: Business Process re-engineering. http://www.apo-tokyo.org/productivity/pmtt_016.htm

- ^ (Covert, 1997)

- (Berman, 1994)

- ^ (Campbell & Kleiner, 1997)

- ^ (Dooley & Johnson, 2001)

- (Jackson, 1997)

- ^ (Motwani, et al., 1998)

- ^ (Al-Mashari & Zairi, 1999)

- (King, 1994)

- (Rastogi, 1994)

- (Barrett, 1994)

- (Carr, 1993)

- (Berrington & Oblich, 1995)

- (Guha, et al., 1993)

- (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993)

- ^ (Vakola & Rezgui, 2000)

- (Malhotra, 1998)

- ^ (Ross, 1998)

- ^ (Weicher, et al., 1995)

- (Broadbent & Weill, 1997)

- ^ (Kayworth, et al., 1997)

- (Malhotra, 1996)

- (Sabherwal & King, 1991)

- (Zairi & Sinclair, 1995)

- ^ (Gore, 1999)

- (Clemons, 1995)

- Hammer, M. and Champy, J. Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution., Harper Collins, New York, 1993

- NYT, Dennis Hevesi / (6 September 2008). "Michael Hammer, who made reengineering a 1990s buzzword". Mint. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- James, Geoffrey (10 May 2013). "World's Worst Management Fads". Inc.com. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- (Davenport, 1995)

- (White, 1996)

Further reading

- Abrahamson, E. (1996). Management fashion, Academy of Management Review, 21, 254–285.

- Champy, J. (1995). Reengineering Management, Harper Business Books, New York.

- Davenport, Thomas & Short, J. (1990), "The New Industrial Engineering: Information Technology and Business Process Redesign", in: Sloan Management Review, Summer 1990, pp 11–27

- Davenport, Thomas (1993), Process Innovation: Reengineering work through information technology, Harvard Business School Press, Boston

- Davenport, Thomas (1995), Reengineering – The Fad That Forgot People, Fast Company, November 1995.

- Drucker, Peter (1972), "Work and Tools", in: W. Kranzberg and W.H. Davenport (eds), Technology and Culture, New York

- Dubois, H. F. W. (2002). "Harmonization of the European vaccination policy and the role TQM and reengineering could play", Quality Management in Health Care, 10(2): pp. 47–57. "PDF"

- Greenbaum, Joan (1995), Windows on the workplace, Cornerstone

- Guha, S.; Kettinger, W.J. & Teng, T.C., Business Process Reengineering: Building a Comprehensive Methodology, Information Systems Management, Summer 1993

- Hammer, M., (1990). "Reengineering Work: Don't Automate, Obliterate", Harvard Business Review, July/August, pp. 104–112.

- Hammer, M. and Champy, J. A.: (1993) Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution, Harper Business Books, New York, 1993. ISBN 0-06-662112-7.

- Hammer, M. and Stanton, S. (1995). "The Reengineering Revolution", Harper Collins, London, 1995.

- Hansen, Gregory (1993) "Automating Business Process Reengineering", Prentice Hall.

- Hussein, Bassam (2008), PRISM: Process Re-engineering Integrated Spiral Model, VDM Verlag

- Industry Week (1994), "De-engineering the corporation", Industry Week article, 4/18/94

- Johansson, Henry J. et al. (1993), Business Process Reengineering: BreakPoint Strategies for Market Dominance, John Wiley & Sons

- Leavitt, H.J. (1965), "Applied Organizational Change in Industry: Structural, Technological and Humanistic Approaches", in: James March (ed.), Handbook of Organizations, Rand McNally, Chicago

- Loyd, Tom (1994), "Giants with Feet of Clay", Financial Times, 5 Dec 1994, p 8

- Malhotra, Yogesh (1998), "Business Process Redesign: An Overview", IEEE Engineering Management Review, vol. 26, no. 3, Fall 1998.

- Ponzi, L.; Koenig, M. (2002). "Knowledge management: another management fad?". Information Research. 8 (1).

- "Reengineering Reviewed", (1994). The Economist, 2 July 1994, pp 66.

- Roberts, Lon (1994), Process Reengineering: The Key To Achieving Breakthrough Success, Quality Press, Milwaukee.

- Rummler, Geary A. and Brache, Alan P. Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organization Chart, ISBN 0-7879-0090-7.

- Taylor (1911), Frederick, The principles of scientific management, Harper & Row, New York]

- Thompson, James D. (1969), Organizations in Action, MacGraw-Hill, New York

- White, JB (1996), Wall Street Journal. New York, N.Y.: 26 Nov 1996. pg. A.1

- Business Process Redesign: An Overview, IEEE Engineering Management Review