A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes (dimensional lumber). The "portable" sawmill is simple to operate. The log lies flat on a steel bed, and the motorized saw cuts the log horizontally along the length of the bed, by the operator manually pushing the saw. The most basic kind of sawmill consists of a chainsaw and a customized jig ("Alaskan sawmill"), with similar horizontal operation.

Before the invention of the sawmill, boards were made in various manual ways, either rived (split) and planed, hewn, or more often hand sawn by two men with a whipsaw, one above and another in a saw pit below. The earliest known mechanical mill is the Hierapolis sawmill, a Roman water-powered stone mill at Hierapolis, Asia Minor dating back to the 3rd century AD. Other water-powered mills followed and by the 11th century they were widespread in Spain and North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia, and in the next few centuries, spread across Europe. The circular motion of the wheel was converted to a reciprocating motion at the saw blade. Generally, only the saw was powered, and the logs had to be loaded and moved by hand. An early improvement was the development of a movable carriage, also water powered, to move the log steadily through the saw blade.

By the time of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, the circular saw blade had been invented, and with the development of steam power in the 19th century, a much greater degree of mechanisation was possible. Scrap lumber from the mill provided a source of fuel for firing the boiler. The arrival of railroads meant that logs could be transported to mills rather than mills being built beside navigable waterways. By 1900, the largest sawmill in the world was operated by the Atlantic Coast Lumber Company in Georgetown, South Carolina, using logs floated down the Pee Dee River from the Appalachian Mountains. In the 20th century the introduction of electricity and high technology furthered this process, and now most sawmills are massive and expensive facilities in which most aspects of the work are computerized. Besides the sawn timber, use is made of all the by-products including sawdust, bark, woodchips, and wood pellets, creating a diverse offering of forest products.

Sawmill process

A sawmill's basic operation is much like those of hundreds of years ago: a log enters on one end and dimensional lumber exits on the other end.

- After trees are selected for harvest, the next step in logging is felling the trees, and bucking them to length.

- Branches are cut off the trunk. This is known as limbing.

- Logs are taken by logging truck, rail or a log drive to the sawmill.

- Logs are scaled either on the way to the mill or upon arrival at the mill.

- Debarking removes bark from the logs.

- Decking is the process for sorting the logs by species, size and end use (lumber, plywood, chips).

- A sawyer uses a head saw (also called head rig or primary saw) to break the log into cants (unfinished logs to be further processed) and flitches (unfinished planks).

- Depending upon the species and quality of the log, the cants will either be further broken down by a resaw or a gang edger into multiple flitches and/or boards.

- Edging will take the flitch and trim off all irregular edges leaving four-sided lumber.

- Trimming squares the ends at typical lumber lengths.

- Drying removes naturally occurring moisture from the lumber. This can be done with kilns or air-dried.

- Planing smooths the surface of the lumber leaving a uniform width and thickness.

- Shipping transports the finished lumber to market.

History

Pre–Industrial Revolution

The Hierapolis sawmill, a water-powered stone sawmill at Hierapolis, Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey, then part of the Roman Empire), dating to the second half of the 3rd century, is the earliest known sawmill. It also incorporates a crank and connecting rod mechanism.

Water-powered stone sawmills working with cranks and connecting rods, but without gear train, are archaeologically attested for the 6th century at the Byzantine cities Gerasa (in Asia Minor) and Ephesus (in Syria).

The earliest literary reference to a working sawmill comes from a Roman poet, Ausonius, who wrote a topographical poem about the river Moselle in Germany in the late 4th century AD. At one point in the poem, he describes the shrieking sound of a watermill cutting marble. Marble sawmills also seem to be indicated by the Christian saint Gregory of Nyssa from Anatolia around 370–390 AD, demonstrating a diversified use of water-power in many parts of the Roman Empire.

Sawmills later became widespread in medieval Europe, as one was sketched by Villard de Honnecourt in c. 1225–1235. They are claimed to have been introduced to Madeira following its discovery in c. 1420 and spread widely in Europe in the 16th century.

Prior to the invention of the sawmill, boards were rived (split) and planed, or more often sawn by two men with a whipsaw, using saddleblocks to hold the log, and a saw pit for the pitman who worked below. Sawing was slow, and required strong and hearty men. The topsawer had to be the stronger of the two because the saw was pulled in turn by each man, and the lower had the advantage of gravity. The topsawyer also had to guide the saw so that the board was of even thickness. This was often done by following a chalkline.

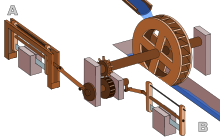

Early sawmills simply adapted the whipsaw to mechanical power, generally driven by a water wheel to speed up the process. The circular motion of the wheel was changed to back-and-forth motion of the saw blade by a connecting rod known as a pitman arm (thus introducing a term used in many mechanical applications).

Generally, only the saw was powered, and the logs had to be loaded and moved by hand. An early improvement was the development of a movable carriage, also water powered, to move the log steadily through the saw blade.

A type of sawmill without a crank is known from Germany called "knock and drop" or simply "drop" -mills. In these drop sawmills, the frame carrying the saw blade is knocked upwards by cams as the shaft turns. These cams are let into the shaft on which the waterwheel sits. When the frame carrying the saw blade is in the topmost position it drops by its own weight, making a loud knocking noise, and in so doing it cuts the trunk.

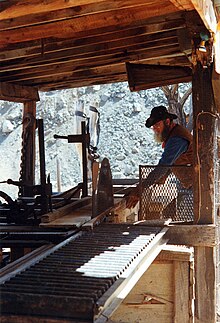

A small mill such as this would be the center of many rural communities in wood-exporting regions such as the Baltic countries and Canada. The output of such mills would be quite low, perhaps only 500 boards per day. They would also generally only operate during the winter, the peak logging season.

In the United States, the sawmill was introduced soon after the colonisation of Virginia by recruiting skilled men from Hamburg. Later the metal parts were obtained from the Netherlands, where the technology was far ahead of that in England, where the sawmill remained largely unknown until the late 18th century. The arrival of a sawmill was a large and stimulative step in the growth of a frontier community.

The Dutch windmill owner Cornelis Corneliszoon van Uitgeest invented in 1594 the wind-powered sawmill, which made the conversion of log timber into planks 30 times faster than before. His wind-powered sawmill used a crankshaft to convert a windmill's circular motion into a back-and-forward motion powering the saw, and was granted a patent for the technique.

Industrial Revolution

Early mills had been taken to the forest, where a temporary shelter was built, and the logs were skidded to the nearby mill by horse or ox teams, often when there was some snow to provide lubrication. As mills grew larger, they were usually established in more permanent facilities on a river, and the logs were floated down to them by log drivers. Sawmills built on navigable rivers, lakes, or estuaries were called cargo mills because of the availability of ships transporting cargoes of logs to the sawmill and cargoes of lumber from the sawmill.

The next improvement was the use of circular saw blades, perhaps invented in England in the late 18th century, but perhaps in 17th-century Netherlands. Soon thereafter, millers used gangsaws, which added additional blades so that a log would be reduced to boards in one quick step. Circular saw blades were extremely expensive and highly subject to damage by overheating or dirty logs. A new kind of technician arose, the sawfiler. Sawfilers were highly skilled in metalworking. Their main job was to set and sharpen teeth. The craft also involved learning how to hammer a saw, whereby a saw is deformed with a hammer and anvil to counteract the forces of heat and cutting. Modern circular saw blades have replaceable teeth, but still need to be hammered.

The introduction of steam power in the 19th century created many new possibilities for mills. Availability of railroad transportation for logs and lumber encouraged building of rail mills away from navigable water. Steam powered sawmills could be far more mechanized. Scrap lumber from the mill provided a ready fuel source for firing the boiler. Efficiency was increased, but the capital cost of a new mill increased dramatically as well.

In addition, the use of steam or gasoline-powered traction engines also allowed the entire sawmill to be mobile.

By 1900, the largest sawmill in the world was operated by the Atlantic Lumber Company in Georgetown, South Carolina, using logs floated down the Pee Dee River from as far as the edge of the Appalachian Mountains in North Carolina.

A restoration project for Sturgeon's Mill in Northern California is underway, restoring one of the last steam-powered lumber mills still using its original equipment.

Current trends

In the twentieth century the introduction of electricity and high technology furthered this process, and now most sawmills are massive and expensive facilities in which most aspects of the work is computerized. The cost of a new facility with 4,700-cubic-metre-per-day (2-million-board-foot-per-day) capacity is up to CAN$120,000,000. A modern operation will produce between 240,000 to 1,650,000 cubic metres (100 to 700 million board feet) annually.

Small gasoline-powered sawmills run by local entrepreneurs served many communities in the early twentieth century, and specialty markets still today.

A trend is the small portable sawmill for personal or even professional use. Many different models have emerged with different designs and functions. They are especially suitable for producing limited volumes of boards, or specialty milling such as oversized timber. Portable sawmills have gained popularity for the convenience of bringing the sawmill to the logs and milling lumber in remote locations. Some remote communities that have experienced natural disasters have used portable sawmills to rebuild their communities out of the fallen trees.

Technology has changed sawmill operations significantly in recent years, emphasizing increasing profits through waste minimization and increased energy efficiency as well as improving operator safety. The once-ubiquitous rusty, steel conical sawdust burners have for the most part vanished, as the sawdust and other mill waste is now processed into particleboard and related products, or used to heat wood-drying kilns. Co-generation facilities will produce power for the operation and may also feed superfluous energy onto the grid. While the bark may be ground for landscaping barkdust, it may also be burned for heat. Sawdust may make particle board or be pressed into wood pellets for pellet stoves. The larger pieces of wood that will not make lumber are chipped into wood chips and provide a source of supply for paper mills. Wood by-products of the mills will also make oriented strand board (OSB) paneling for building construction, a cheaper and in some use cases more robust alternative to plywood for paneling. Some automatic mills can process 800 small logs into bark chips, wood chips, sawdust and sorted, stacked, and bound planks, in an hour.

Gallery

-

Inside a modern sawmill equipped with laser-guided technology

Inside a modern sawmill equipped with laser-guided technology

-

Wood traveling on sawmill machinery

Wood traveling on sawmill machinery

-

Sawdust waste from the mill

Sawdust waste from the mill

-

A sawmill in Armata, on mount Smolikas, Epirus, Greece

A sawmill in Armata, on mount Smolikas, Epirus, Greece

-

A preserved water powered sawmill, Norfolk, England

A preserved water powered sawmill, Norfolk, England

-

Making planks from logs

Making planks from logs

-

Sawmill in Luchon, France, near 1840 by Eugène de Malbos

Sawmill in Luchon, France, near 1840 by Eugène de Malbos

-

Sawmill workers posing with saw blades, Rainy River District, 1900–1909

Sawmill workers posing with saw blades, Rainy River District, 1900–1909

-

Sawmill with the floating logs in Kotka, Finland

Sawmill with the floating logs in Kotka, Finland

-

Logs at sawmill at Manitoulin Island

Logs at sawmill at Manitoulin Island

See also

- Band saw

- Circular saw

- Hewing

- Log bucking

- Logging

- Lumber yard

- Portable sawmill

- Saw pit

- Sawfiler

- Wood drying

References

- "Lumber Manufacturing". Lumber Basics. Western Wood Products Association. 2002. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 161

- Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 149–153

- ^ Wilson 2002, p. 16

- C. Singer et at., History of Technology II (Oxford 1956), 643-4.

- ^ Peterson, Charles E. (1973). "Sawdust Trail: Annals of Sawmilling and the Lumber Trade from Virginia to Hawaii via Maine, Barbados, Sault Ste. Marie, Manchac and Seattle to the Year 1860". Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. 5 (2): 84–153. doi:10.2307/1493399. JSTOR 1493399.

- "Die Sägemühle". www.familienverband-tritschler.de (in German). Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- "Cornelis Corneliszoon van Uitgeest (1550–1607), inventor of the wind powered saw mill", Industrial Heritage Park De Hoop Archived 2006-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Dutch inventions Archived 2011-07-04 at the Wayback Machine by Cornelisz van Uitgeest in the National Archives (Dutch)

- ^ Oakleaf p.8

- Norman Ball, 'Circular Saws and the History of Technology' Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology 7(3) (1975), pp. 79-89.

- Edwardian Farm: Roy Hebdige's mobile sawmill

- "RitchieSpecs Equipment Specs & Dimensions". www.ritchiespecs.com.

- "Reap the Profits of Mobile Milling". Trees 2 Money. 21 January 2016. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

Sources

- Grewe, Klaus (2009), "Die Reliefdarstellung einer antiken Steinsägemaschine aus Hierapolis in Phrygien und ihre Bedeutung für die Technikgeschichte. Internationale Konferenz 13.−16. Juni 2007 in Istanbul", in Bachmann, Martin (ed.), Bautechnik im antiken und vorantiken Kleinasien (PDF), Byzas, vol. 9, Istanbul: Ege Yayınları/Zero Prod. Ltd., pp. 429–454, ISBN 978-975-8072-23-1, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-11

- Ritti, Tullia; Grewe, Klaus; Kessener, Paul (2007), "A Relief of a Water-powered Stone Saw Mill on a Sarcophagus at Hierapolis and its Implications", Journal of Roman Archaeology, vol. 20, pp. 138–163, doi:10.1017/S1047759400005341

- Oakleaf, H.B. (1920), Lumber Manufacture in the Douglas Fir Region, Chicago: Commercial Journal Company

- Wilson, Andrew (2002), "Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy", The Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 92, pp. 1–32, doi:10.2307/3184857, JSTOR 3184857

External links

- Steam powered saw mills

- The basics of sawmill (German)

- Nineteenth-century sawmill demonstration

- Database of worldwide sawmills Archived 2017-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Reynolds Bros Mill, northern foothills of Adirondack Mountains, New York State

- L. Cass Bowen Mill, Skerry, New York

| Forestry | |

|---|---|

| Types | |

| Ecology and management | |

| Environmental topics |

|

| Industries | |

| Occupations | |