| Château de Challain-la-Potherie | |

|---|---|

North facade of Château de Challain. North facade of Château de Challain. | |

| Alternative names | Château de Challain |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neo-gothic |

| Town or city | Challain-la-Potherie, Maine-et-Loire, Pays de la Loire |

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 47°38′06″N 1°02′39″W / 47.63500°N 1.04417°W / 47.63500; -1.04417 |

| Construction started | 1847 |

| Completed | 1854 |

| Owner | La Rochefoucauld-Bayers family (Original owner); Nicholson Family (Current owner) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | René Hodé |

| Designations | Registered as MH (1980, 2004) |

The Château de Challain-la-Potherie is a castle located in the French commune of Challain-la-Potherie, in Maine-et-Loire. Constructed between 1847 and 1854 in the neo-Gothic style, the Château de Challain-la-Potherie is a notable example of French architectural heritage. René Hodé, the architect responsible for the design, is also known for his work on numerous other castles in the same style in Anjou. Its considerable size and impressive grandeur have earned it the sobriquet "Petit Chambord" or "Chambord angevin."

The current building replaces an older castle with origins dating back to the Middle Ages. Formerly the seat of the seigneurie of Challain, it changed ownership through various families throughout its history. Through sales and inheritances, it passed to the Châteaubriant family and then the Chambes family before being inherited by Nicolas Fouquet's family members. Eventually, it came into the possession of the La Potherie family, who named the castle and village after themselves.

The 19th-century castle was commissioned by Louise-Ida Le Roy de La Potherie (1806–1884) and her husband François Albert de La Rochefoucauld, Comte de Bayers (1799–1854), the last of her line. They chose the neo-Gothic style to restore their family's glory after the French Revolution and because it was fashionable among the Angevine aristocracy at the time. René Hodé adopted the Troubadour style, which overlays a neo-medieval décor onto a functional structure. The castle's internal structure and general layout follow the neoclassical architectural rules developed in the 18th century.

Despite its architectural significance and grandeur, the building underwent a period of decline following the death of its commissioners. It was subsequently owned by numerous individuals and institutions in the 20th century, including a period as a summer camp center. In 2002, the building was transformed into a luxury bed and breakfast.

Location

The Château de Challain is situated in the commune of Challain-la-Potherie, in Maine-et-Loire, on the western border of the department. Before the dissolution of the provinces of France during the Revolution, Challain was part of Anjou, while the neighboring commune of Vritz to the south was part of Brittany. Challain-la-Potherie is located between Angers and Châteaubriant, near the small town of Candé.

The castle is situated in the village of Challain. It is adjacent to the parish church, and the main gate opens onto the church square. The estate occupies a quadrilateral bordered by Rue de l'Étang to the north and Route de Candé to the west. Additionally, part of the estate lies outside this quadrilateral. The Basse-Cour and the vegetable garden are located on the opposite side of Route de Candé, while the orangery is on the opposite side of Rue de l'Étang. This latter street offers an unobstructed view of the castle's north façade and provides access to the estate through the Monplaisir Tower, working as a secondary entrance.

The castle is situated on a small natural terrace that overlooks the Argos River, which flows from north to south across the property. To the north, a dam that once powered a watermill has created a pond. The estate is also crossed by the Planche Ronde stream, which flows from west to east and joins the Argos within the park, southeast of the castle. The stream feeds a second pond at the southern edge of the park.

History

Old castle

Appearance

Challain-la-Potherie has had a castle since the Middle Ages, with the current structure replacing a medieval building. The history of the old castle is poorly documented, with only one illustration of it, made in 1842 by Théodore de Quatrebarbes, available. This image depicts an L-shaped building, plain in appearance and surrounded by service buildings. In his work History of the Barony of Candé, published in 1894, René de l'Esperonnière, a local historian of the nineteenth century, describes the castle.

The ancient residence, which exhibited a uniform appearance, was constructed with a single story above the ground floor and attics. It was preceded to the north by a green courtyard framed by service buildings. The entire complex was surrounded by moats on three sides. The west part, boarding the road to Candé, was bounded by a lime tree alley. Nearby stood a labyrinth, an ancient mound that was five to six meters high. This mound was leveled around 1840. At the northeast corner of the moats, the former lords had constructed a tower, which was transformed into a dovecote at the beginning of the 19th century. This tower housed two to three hundred pigeons and was demolished around 1835. Another larger tower defended the northwest corner; it was once the prison. This tower was destroyed in 1827.

Successive owners

The castle is the seat of the seigneurie of Challain, and its existence dates back at least to the 11th century. The first lord of Challain may be Hilduinus de Calein, mentioned as a witness around 1050 in a charter. Around 1120, probable descendants of Hilduinus, named Rainaud, Warin, and Haï de Challain, appear in the cartulary of Saint-Nicolas Abbey in Angers. Thereafter, no lords of Challain are mentioned before the early 13th century. The village then belonged to Guillaume de Thouars, lord of Candé and Lion-d'Angers. His descendants were part of the Châteaubriant family, which owned Challain for approximately two centuries.

In 1284, following an inheritance division, Challain came under the ownership of a cadet branch of the Châteaubriant family, which retained control of the village and its castle until its extinction around 1522, marked by the death of Marie de Châteaubriant. She had married Jean III de Chambes, the lord of Montsoreau, the son of Jean II de Chambes, the builder of Château de Montsoreau and the first advisor to Charles VII. Their son, Philippe de Chambes, and their grandson, Jean IV, both attempted to sell Challain, with the latter successfully doing so in 1574. The new proprietor, Antoine d'Espinay, a former page to Henry II, resided at Saint-Michel-du-Bois and left the castle of Challain to a steward. His widow sold the property to Christophe Fouquet in 1599. Fouquet, the president of the Parliament of Brittany, primarily lived in Rennes but occasionally visited Challain. He had plans to rebuild the dilapidated castle but instead chose to establish a Carmelite convent in Challain. His grandson, also named Christophe, was granted the title of Viscount of Challain in 1650, and the castellany was elevated to a county seven years later.

In 1747, the heirs of the Fouquet family sold Challain and its castle to Urbain Le Roy, the lord of La Bourgonnière. The title of Count of Challain, which had become extinct with the last Fouquet in 1722, was revived in 1749 as "Count of La Potherie". Urbain's grandson, Louis Le Roy de La Potherie, emigrated during the Revolution but returned to France in 1801 and actively participated in the military and political life of the Restoration period. He held the positions of marshal and deputy. Unfortunately, his only son, Charles, met his demise in a duel in 1825. Upon Louis's demise in 1847, his estate was inherited by his daughter, Louise-Ida, who was born in 1808.

In 1826, Louise-Ida Le Roy de La Potherie married François Albert de La Rochefoucauld, Count of Bayers, son of Jean de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers, members of a cadet branch of the House of La Rochefoucauld. This branch, which originated from one of the oldest families of French nobility, included a Count-Bishop of Beauvais, a Bishop of Saintes, a Peer of France, and a deputy to the Estates-General of 1789. The marriage combined the prestigious name and wealth of the La Rochefoucauld family with the equally significant fortune of the La Potherie family. Later, the Count of Bayers settled in Challain, where he assumed the role of mayor and served as a General Councilor of Maine-et-Loire.

Current castle

Construction background

During the French Revolution, numerous nobles from western France, including the Le Roy de La Potherie and La Rochefoucauld families, managed to retain their properties. Following the tumultuous period, Angevin aristocrats returned from exile in England and aspired to emulate the English aristocracy, who owned vast estates with castles and extensive farmlands. Consequently, new estates emerged in Maine-et-Loire, including Challain. The Count of La Potherie undertook a restructuring of his lands, consolidating them around the castle to increase profitability. Despite his efforts, he could not match the grandeur of English estates, acquiring only 596 hectares through purchases and exchanges. He encountered difficulties in creating a contiguous estate, as negotiations to reroute village communication routes in Challain were unsuccessful. Consequently, the domain continued to be intersected by roads.

The emigrants spent a brief period on their lands following the Bourbon Restoration, which reinstated their position at the pinnacle of the social hierarchy. They had access to public offices and led relatively simple lives, with their nobility automatically setting them apart from the rest of the population. However, they experienced difficulty in reestablishing themselves on their lands. They lacked the confidence to resume their seigneurial role and were confronted with the servitudes of the Ancien régime, perpetuated by peasants who still claimed rights of passage, gleaning, or grazing on the lands. The Count of La Potherie had a brief history of owning his property, as the family had only acquired it in the 18th century. In contrast, the next generation, the Count and Countess de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers demonstrated a growing interest in land ownership. This generation assumed power following the July Revolution, which ended the Bourbon Restoration and resulted in the ascension of a more liberal king, Louis-Philippe, to the throne. They had lost numerous social privileges during the revolution and sought to maintain their position in the social hierarchy by returning to the countryside. In this context, industrialization had not yet enriched a competing bourgeoisie, and they could still exert public influence. Furthermore, the banking or industrial bankruptcies that occurred around 1840 demonstrated that agriculture remained a stable and secure source of income. Many Angevin aristocrats became interested in agronomy and focused on developing livestock by improving breeds.

Origins

The aristocrats of 1840 had experienced the comfort of Parisian hotels and, when they decided to spend more time on their lands, they were not satisfied with their ancestors' old country houses. They therefore replaced them with new castle. The trend of reconstructing Angevin castles began in the 1830s and became an phenomenon in the 1840s. The most sought-after architectural style was neo-Gothic, which originated in England in the 18th century. It appeared in Anjou around 1835, and its popularity among the local aristocracy can be explained by a desire to return to the ideals of the Ancien régime, which included feudalism, religion, and continuity with the past. It can also be viewed as a reactionary act against the prevailing neoclassical architecture, which was associated with the aesthetic and cultural ideas of the Lights and the Revolution.

Guy Massin-Le Goff, a curator of antiquities and art objects in Maine-et-Loire and a specialist in Angevin neo-Gothic, offers an alternative explanation for the style popularity. He suggests that the appeal of the style is rooted in familial passion. Many of the castles in this style in Anjou are owned by families with close relationships. The first truly reconstructed Angevin castle in a neo-Gothic style is located in Angrie, approximately ten kilometers from Challain. It belongs to the Lostanges family, with Madame de Lostanges being a cousin of Louise-Ida de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers and the painter Lancelot-Théodore Turpin de Crissé. Turpin de Crissé, a prominent figure in Parisian salons, was an admirer of ancient architecture and a friend of the architect Louis Visconti, who designed Napoleon's tomb. Encouraged by Turpin de Crissé, the Lostanges family sought plans for a new castle from Visconti, who, due to the distance, delegated the project to the local architect René Hodé, partly funded by the Lostanges. The new castle was completed in 1847. Another cousin of Louise-Ida and Madame de Lostanges, Théodore de Quatrebarbes, had his Château de Chanzeaux rebuilt by René Hodé, also completed in 1847. A medieval enthusiast, particularly of King René's reign and the 15th century, Quatrebarbes likely contributed to the neo-Gothic style establishment in Anjou with his reputation as an art lover.

The Château de Challain, an ancient building that had survived the test of time, was still in good condition and large enough to accommodate an entire family. Therefore, the construction of the new castle can be viewed as a pursuit for wealthy individuals or a means to uphold family prestige. The project also demonstrated an intention to rival the Lostanges and Quatrebarbe relatives. The La Rochefoucauld-Bayers couple initially sought plans from architect Châtelain in 1835, but these were not pursued. Subsequently, they engaged the services of other architects, including Visconti, in 1846. They focused on the interior layout, which needed to be classical, rather than the exterior design. Visconti initially proposed a rectangular building with four corner towers in a Renaissance style, but they preferred a neo-Gothic exterior inspired by the new castles of Angrie and Chanzeaux. Due to Visconti's unavailability in Anjou, Hodé was tasked with finalizing the plans. He maintained Visconti's structural concept but envisioned a castle influenced by his previous works, in a more grandiose style.

Construction

The construction of the new castle started in 1847 and was notable for its speed and the large number of workers employed on the site, which numbered over 700. The new building was erected a few meters away from the old castle, which was preserved during the construction. The work was briefly interrupted by the 1848 Revolution, and the site was left abandoned under protective cover for a few weeks. However, the Count de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers was eager to resume work promptly, demonstrating consideration for the workers and loyalty to the contractors. The exterior of the castle was completed in 1851, and the interiors were finished in 1854 by René Hodé's original plans, with no alterations. The total cost of the castle's construction amounted to 280,000 francs.

The Count de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers died in January 1854 in the old castle, just as construction work was nearing completion. He left behind his widow and two children, Henri, aged twenty-six, and Marie, aged ten. Despite this loss, the countess continued the project, demolishing the old castle and overseeing interior renovations between 1855 and 1858. Later, her attention was directed towards the remainder of the estate, with the park being designed in 1860, the outbuildings completed in 1859–1860, the north enclosure wall, orangery, and greenhouses in 1866, the Monplaisir tower in 1875, and the entrance gatehouse in 1882. After this, additional decorative and leisure elements were incorporated, including a dock on the pond and an array of artificial ruins.

Louise-Ida dedicated thirty-six years of her life to Challain, yet she spent little time there, dividing her time between the Château of Soucelles near Angers, which she preferred, and her Parisian residence. During her stays at Challain, she appeared to live in solitude with her servants, grieving the loss of her husband and her daughter Marie, who died in 1868. The castle, designed for social gatherings and celebrations to showcase the La Rochefoucauld-Bayers' family life, probably have hosted a few significant events during this period. The numerous guest rooms were probably not used. Louise-Ida died in 1884 at Soucelles, leaving the property to her son, Henri de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers.

Successive owners

Henri de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers, who appeared to have little regard for Challain, died without children in 1893. Following his death, the castle changed hands several times through various sales and resales. Henri's heir, the Viscount of Rochebouët, decided not to retain the extensive property and sold the castle to Marquis Albert Courtès in 1894. The Marquis, a Roman noble claiming lineage from Hernán Cortés, served as an artillery lieutenant and later rose to the rank of general. Although he and his wife only occasionally resided at Challain until 1907, they undertook significant restoration work to revive the castle's grandeur. The Courtès family preserved the existing decorations while adding some personal touches, such as displaying their coat of arms above the entrance and in the vestibule. Following the Marquis's demise in 1931, his spouse and two adopted daughters inherited his assets. The castle was bequeathed to his spouse and subsequently to the eldest daughter, Marquise Jeanne Brunet de Simiane. Upon her demise in 1944, her sole son declined the inheritance.

In 1948, the Château de Challain was purchased by the city of Choisy-le-Roi in Île-de-France. The municipality used the property for summer camps, accommodating two hundred children each summer. However, the camps ceased in 1970, and the castle was sold again in 1978. The new proprietor, an industrialist from Saint-Leu-la-Forêt, who was the president of the International Federation of Esotericism and Naturopathy, established a club there called "Ondes vives." In 1989, the castle was acquired by the European Property Management Society (SEGI), which was associated with the Unification Church, also known as the "Moon sect." The society proceeded to expand the estate and planned to transform it into a hotel and golf course.

The project was ultimately abandoned, and in 1996, a real estate company assumed ownership of the castle. At that time, the property was valued at approximately ten million francs, which is equivalent to nearly two million euros in 2016. Before the Nicholson family's acquisition in 2002, the castle had been owned by several other parties. The Nicholson family, originally from New Jersey in the United States, owned a construction company. Following nine months of renovation, the first guest rooms were opened to the public. Since that time, the castle has operated as a high-end bed and breakfast establishment. The property specializes in hosting weddings and has an international clientele. Approximately twenty ceremonies are held there each year.

The castle was designated as a historical monument in two stages. Initially, the decree of 30 July 1980, included the facades, roofs, and several rooms such as the hall, chapel, grand salon, and library. Subsequently, a new decree on 15 March 2004, encompassed the entire basement and ground floor, along with the park and its components. These included the facades and roofs of the outbuildings, the gatehouse, the Monplaisir tower, the Basse-Cour farm, the icehouse, artificial ruins, gardeners' lodgings, vegetable garden enclosure, a moat with water, and boundary wall. In a decree dated 4 July 2019, specific elements of the orangery were classified, including facades, roofs, the entire greenhouse, two ornamental vases, the foundation soil of the buildings, boundary walls, underground passage, and markers indicating the property boundary, pond, and banks.

Architecture

Exteriors

Exterior architecture

The castle is designed in a rectangular layout with corner towers at each corner and a square "keep" at the center. The building measures 60 meters in length and 37 meters in width, with truss peaks reaching a height of 45 meters. Constructed primarily from tuffeau stone sourced from the Saumur region, the foundations are made of granite from Bécon, and the steps are crafted from granite from Louvigné-du-Désert. The facades facing north and south each have thirteen bays, excluding the towers, and are adorned with 55 windows on each side. Due to its grand proportions, the castle is often referred to as the "Angevin Chambord" or "Little Chambord."

The 19th century was marked by eclectic architectural trends, yet French castles from this period exhibit certain commonalities. Challain is a notable example, featuring an elevated ground floor above a service basement constructed from different stones. Access to the ground floor is through grand steps, a prominent element in castles design that harks back to medieval justice steps. Furthermore, the castle at Challain features steep slate roofs, a common architectural element of the era. These roofs evoke a sense of spirituality, reminiscent of church spires, despite the maintenance challenges they have.

Challain in René Hodé's work

The Château de Challain represents a significant contribution to the architectural oeuvre of René Hodé, marking a pivotal moment in his career. It solidified his reputation in Anjou and led to a busy workload until he died in 1874. The Count of La Rochefoucauld-Bayers recognized the project potential and expressed confidence in Hodé's abilities, stating that the castle would enhance the architect's standing. By 1862, the Château de Challain was already regarded as Hodé's masterpiece by Baron Olivier de Wismes. Following Challain, Hodé's projects returned to a more modest scale, as he did not attract clients of similar wealth. The Château de Challain served as a blueprint for the design of La Baronnière, constructed for the count's brother. In comparison to Hodé's other works, the Challain project appears to be an ambitious undertaking, possibly indicating that he collaborated closely with the original neo-Renaissance concept by Louis Visconti in 1846. The incorporation of modern techniques and innovations in Challain suggests that Hodé may not have conceived the project independently.

Born in 1811 into a legitimist family, Hodé maintained this political orientation throughout his life. Consequently, he never received public commissions and primarily designed private residences, mostly castles. His portfolio includes fourteen castles, three restored castles, and other more modest houses he designed. Nearly all his works are located in Maine-et-Loire. The rectangular plan flanked by four corner towers, topped with a keep, is a constant feature among René Hodé's castles. All lines direct the gaze upward; no horizontal bands are marking the transition between floors, but pinnacled dormers, narrow chimneys that rise to the roof ridge, and pointed turrets. Balconies and shutters are absent, leaving the facade smooth and forming a closed envelope isolated from the surrounding environment. Similarly, a vast embankment extends around the foundation, thereby distancing the castle from vegetation.

A "troubadour" castle

Hodé was a pivotal figure in the troubadour movement, distinguishing himself from other prominent neo-Gothic architects such as Eugène Viollet-le-Duc by not prioritizing historical accuracy. His objective was to create an idealized and romanticized vision of the Middle Ages, offering a Utopian portrayal of feudalism. This revival sought to bring back a heroic and dark era during a time considered mundane and unremarkable by the legitimist aristocracy. The architectural style known as the troubadour style drew inspiration from literature and took a loose approach to historical accuracy, deviating from traditional medieval construction methods. While the Château de Challain is adorned with neo-Gothic decorations, its underlying structure and layout adhere to neoclassical architectural principles. The Gothic influence is primarily seen in the decorative elements, as the facades maintain a symmetrical classical design, and the room distribution follows neoclassical conventions. The decorations are applied to a modern architectural framework, without which Challain would lack the Gothic aesthetic that defines it. The side towers resemble those found in classical castles, while the central keep serves as a prominent feature. The traditional flat neoclassical roofs have been replaced with elaborate attics, further enhancing the Gothic appearance of the structure.

The troubadour style persisted longer in Anjou compared to the rest of France, largely due to the enduring popularity of René Hodé's work. By 1840, neo-Gothic architects had embraced more scientific approaches, resulting in buildings that featured not just Gothic decoration but also Gothic structure. However, by 1850, the use of the troubadour style had become exceedingly rare in France. It seems unlikely that René Hodé was acquainted with the work of Viollet-le-Duc, a prominent figure in the neo-Gothic movement in France. Most neo-Gothic castles in Anjou had already been constructed when Viollet-le-Duc initiated the reconstruction of the Château de Pierrefonds in 1858.

Inspirations and decor

The Château de Mehun-sur-Yèvre and Saumur in Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, direct influences from Challain.

The Château de Mehun-sur-Yèvre and Saumur in Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, direct influences from Challain.

Throughout his career, René Hodé explored a variety of architectural styles and applied them to his castle based on the owners' preferences. His inclination, however, was towards transitional Gothic, a decorative style that emerged in the Loire Valley during the reigns of Louis XI and Charles VIII, just before the Renaissance architecture took hold. The design of the Château de Challain draws inspiration from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, a 15th-century manuscript that reflects the transition from Gothic to Renaissance styles. Challain's silhouette is notably influenced by the Châteaux de Saumur and Mehun-sur-Yèvre, featuring a rectangular plan with prominent corner towers. In Anjou, the latter half of the 15th century, especially during the reign of King René, sparked significant interest, leading to a resurgence of regionalist and anti-Parisian architectural trends. René Hodé's architectural work aligns with this trend, as artists sought inspiration from Anjou's rich heritage. Publications such as L'Anjou et ses monuments by Godard-Faultier (1839–1840) played a pivotal role in disseminating the region's architectural gems among the local elite. Hodé's castles, which combine medieval decorative elements with classical structures, exemplify a design approach previously observed in castles such as du Lude and Landifer in Baugé during the 16th century.

The facades of the castle are adorned with numerous small sculptures created by Jacques Granneau, a student of David d'Angers. These sculptures are primarily located in the corbels of the water spouts on the ground and first-floor windows. There are 184 corbels on the castle's facades, with 96 of them being sculpted. The intricately crafted figures, including musicians, acrobats, jesters, knights, and real or imaginary animals, are arranged without a specific organizational scheme. However, they are mostly found on the lower, more visible corbels, while the higher floors are decorated with simpler vegetal motifs. One of the figures is an architect holding a plan of the castle. Granneau frequently collaborated with Hodé and contributed to the decoration of several other castles designed by the architect. The window sills on the ground floor display different motifs for each opening, and the central keep is adorned with finialed gables, lancet windows, and coats of arms. The upper levels and first attic floor of the castle are embellished with an exaggerated pseudo-medieval decor, featuring tall dormers and false battlements. The towers are decorated with corbelled turrets, and the roofs are crowned with large finials, enhancing the castle's slender appearance. The ornamentation, which fills the large blank areas of the facades and enlivens the roofs, accentuates the building's height, balancing its grand and powerful presence. The overall result is a harmonious structure with an impressive yet not austere silhouette. The decorative scheme focuses on the abundance of ornamentation crowning the building and the harmony of the bays and blank areas on the facades.

Interiors

General organization

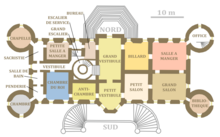

The castle comprises a basement, two principal floors, an additional floor, and two attic levels, for a total of six levels. The towers have four levels, including one attic. The first five levels house nearly 120 rooms; each level covers approximately 800 m². René Hodé designed the interior layout to align with the preferences of the Count and Countess of La Rochefoucauld-Bayers, who desired a classical organization with an axial plan. The layout opens to reception rooms on the left and to the owners' and guests' chambers on the right, with approximately ten chambers also located on the first floor. The castle reflects the tastes of the 19th century and incorporates modern amenities of the time, such as bathrooms and central heating provided by a basement calorifer and an air conduit network. The central staircase, designed in a neo-Gothic style, is constructed from stucco supported by a cast iron frame, with cast iron pillars supporting the vestibule gallery. A skylight on the roof illuminates the staircase. Several modern and innovative techniques were employed, including compartmentalized parquet floors and a mechanism that allows the double doors of the grand salon to open simultaneously. These innovations were likely the work of Louis Visconti, given that René Hodé had received his training more traditionally and provincially.

Ground floor organization

The elevated ground floor of the castle is the noble floor, housing reception rooms organized around a central north-south axis with two vestibules. One vestibule opens to the courtyard to the north, while the other opens to the park and pond to the south. The grand vestibule to the north follows an Italian-style layout, with a mezzanine gallery on the first floor and access to the grand spiral staircase. The eastern part of the castle contains the billiard room, dining room, grand salon, and petit salon. The southeast tower connects to the grand salon and houses the library, which is accessed via a faux-gothic vaulted ceiling. The northeast tower, connected to the dining room, contains the pantry, dumbwaiter, and service staircase leading to the basement kitchens. The western part of the castle features more intimate rooms, including a study, small dining room, sacristy, and a suite with an antechamber, honor chamber, wardrobe, and bathroom. The southwest tower holds another chamber, while the northwest tower houses the chapel with a faux-gothic vaulted ceiling, spanning two levels with a vault reaching the first-floor ceiling.

The architect René Hodé sought to create a castle that combined modern design with a medieval appearance. This presented a unique challenge due to the wider main building compared to traditional structures. The inclusion of corner towers and the desire to evoke fortified castles necessitated a substantial thickness for the rectangular structure, which resulted in difficulties in organizing the interior spaces and larger rooms than usual. In the eastern part of the castle, the challenge was addressed by constructing spacious rooms, such as the grand salon and dining room, each measuring 10 meters in length. However, the western part presented a more complex design problem, requiring smaller, more intimate rooms. René Hodé resolved this by creating multiple small rooms, which resulted in some areas being redundant or less functional, such as the small dining room, sacristy, and study.

Basement organization

The basement consists of service rooms arranged along a central corridor, which include the kitchen, storage rooms such as cellars, and staff facilities. Additionally, it houses the boiler room with the calorifer. The architect paid attention to detail in the basement, providing impressive ceilings for the rooms. The boiler room boasts a basket-handle vault, similar to the central servants' room, while the corridor has a broken barrel-shaped vault. The kitchen, scullery, and servants' dining room feature intricate ribbed vaults, while the wood store has a cloister vault on an octagonal plan. The tower rooms are crowned with domes. Some basement rooms may appear excessive, potentially filling the void created by the building's width. This layout offers the staff both a dining room and a lounge for their use.

Floor organization

The first floor of the castle comprises approximately ten rooms, designed to accommodate the owners and their guests. These rooms are arranged in suites, accompanied by bathrooms and smaller rooms intended for valets or maids. As in the design of the ground floor, René Hodé faced the challenge of the building's significant width. He could not design excessively long rooms or place a too-wide central corridor. However, he opted for the latter solution, mitigating the width of the corridor by placing pillars in the center, creating the illusion of two separate, parallel corridors. These pillars also serve to solve structural problems by acting as load-bearing walls. At the time of the castle's construction, the master of the house typically occupied a room in a corner, from where he could oversee the comings and goings of his staff, while his wife had a neighboring room. The second floor was allocated to the servants' quarters, while the attic levels were likely never occupied. In a fully used castle, the second floor would have been dedicated to children and senior staff, while the servants would have occupied the garrets under the eaves. The attic levels are devoid of comfort amenities, with few fireplaces and only a few rooms receiving sufficient natural light from large dormers. In contrast, other rooms have small openings that resemble half-windows or faux arrow slits.

Decoration and furnishing

René Hodé was not particularly concerned with the interior decoration of his castles. He generally provided broad directions, such as suggesting 15th-century napkin-fold motifs and recommending sculptor Granneau to deploy the same profusion of sculptures as seen on the exterior. At Challain, only the ground floor features neo-Gothic decor; the chambers on the upper floors are furnished in a bourgeois style. This limitation of the neo-Gothic style to reception rooms is also observed in his other castles. The style is reserved for rooms with a symbolic function, evoking the family's glorious past. Thus, the grand salon's fireplace at Challain includes an equestrian statue of François I de La Rochefoucauld, the godfather of King François I. In contrast, personal use rooms are meant to be modern. The original ground-floor decoration has been relatively well preserved despite numerous ownership changes. The finest rooms were listed as historical monuments in 1980, before the subsequent extension of protection to the entire level and the basement in 2004.

The interior decoration of the Angevin style seems to derive from theatrical sets. The first examples of neo-Gothic interiors in the province were created by theater decorator Eugène Cicéri around 1840 at the Château de Brézé. Another theater decorator, Achille Léger, decorated the Château d'Angrie. At the time, there were no books or publications dedicated to neo-Gothic decorative principles. The enthusiasm for the style resulted in a blend of theatricality and comfort, combining decorative overload with practical and comfortable furnishings. At Challain, the interior decoration was conceived before the completion of construction. The decorating team was tasked with offering a decorative progression that increased in grandeur from the vestibule to the ceremonial apartments and salons, and included sculptor Jacques Granneau, upholsterer Didier, and furniture maker Jean-Paul Mazaroz, a supplier to Napoleon III. The interior decoration had to be equally sumptuous, matching the exterior splendor. It showcases a profusion of wood paneling sculpted with lancet window motifs and designs inspired by the doors of Rhodes in the Crusades halls of the Château de Versailles. The furniture features flamboyant Gothic decorations treated with profusion but delicacy. The multitude of details and the fineness of the sculpture avoid heaviness. Additionally, napkin-fold motifs, vegetal designs, and fantastical creatures are observed on stucco and more discreet elements such as window espagnolettes. The wallpaper, which is industrially produced, displays medieval twisted or corded motifs, which are used to highlight corners or ceiling cornices. The colors are vivid, with striking chromatic contrasts being fashionable at the time, superimposed on the dark tones of the woodwork.

The arms of the La Rochefoucauld and La Potherie families, accompanied by their initials, "R" and "P," are pervasive in the architectural ornamentation. They are visible on doors, ceilings, corbels, and fireplaces. The chapel features large stained-glass windows dedicated to family members, depicted by saints associated with personal coats of arms. For example, Charles Borromeo is depicted above the arms of La Potherie, Saint Louis above the arms of La Potherie and de la Marsaulaye, Saint Albert, the Virgin Mary, and John the Baptist above the La Rochefoucauld arms, the Virgin Mary above a split La Rochefoucauld and Mauroy coat of arms, and Saint Ida above a split La Rochefoucauld and La Potherie coat of arms.

- Images of the castle's rooms

-

Grand vestibule and its Italian-style gallery.

Grand vestibule and its Italian-style gallery.

-

Grand spiral staircase.

Grand spiral staircase.

-

Billiard room.

Billiard room.

-

Dining room.

Dining room.

-

The King's bedroom.

The King's bedroom.

Estate

Park

The park at Château de Challain exemplifies the characteristics of a 19th-century private park, diverging from the rigid symmetry of French neoclassical gardens in favor of the picturesque English garden. Its primary purpose is ornamental, concealing practical functions related to the estate's profitability. The village, outbuildings, and enclosing walls are concealed by greenery, while cultivated lands are extended beyond the meadows surrounding the estate. The path leading to the castle approaches from one side, facing the north façade, and leaves the south façade, which overlooks the park, free of vehicles. In place of traditional chestnut trees, horse chestnuts have been planted, and fruit trees are secluded in a hidden orchard. A mix of tree species creates color variations and alleviates the winter landscape's starkness. Oak trees, cedars, and sequoias have been strategically placed to enhance the park's grandeur. The park, spanning approximately 30 hectares, includes meadows and forests that have been skillfully designed to create the illusion of depth and undulation through the arrangement of trees and woodland edges.

The La Rochefoucauld-Bayers had the park's layout in mind since the construction of the castle. They sought plans from Count de Choulot, who was also involved in designing numerous other castles in the region. Around 1850, he proposed an expansive park that would stretch south to the hamlets of Choiseau and Argos, featuring vast lawns, meadows, woods, and groves. He also proposed the creation of a pond on the Planche Ronde stream and the widening of the rectangular moats to soften their geometric appearance.

However, this ambitious plan was never carried out, and the park was eventually designed by another landscaper, Châtelain. The final result was more modest than the original vision and did not match the grandeur of the finest parks in Anjou, like Chanzeaux. The challenging terrain at Challain did not permit the creation of distant perspectives, resulting in a park that felt somewhat confined. Furthermore, the La Rochefoucauld-Bayers were obliged to accept that the Loiré road divided their estate, with the castle and its outbuildings located to the south of the road and one of the ponds and the orangery to the north. Despite the division, the decision to use a ha-ha instead of a wall to separate the castle from the road helped to maintain some visual continuity, thus ensuring that the castle remained prominently visible from the orangery.

Ponds

In the 19th century, the castle had two ponds. One was situated at the bottom of the park on the south side, while the other in the north of the Loiré road. The smaller pond, created during the park's development, features a wooded island. The larger pond, separated from the castle estate in the 20th century and transformed into a municipal area, has a history dating back to the Middle Ages when it served as a reservoir to power a water mill. The mill, initially constructed in the 15th century, was destroyed and rebuilt on multiple occasions, with the last reconstruction taking place in 1843.

Ponds were a fundamental element of the 19th-century park landscape. In addition to enhancing the landscape, they served as a pretext for walks and fish-holding, and could also be used for boat excursions. Such ponds are frequently accompanied by an "isle of Venus," as exemplified by Challain's southern pond, which is planted with poplars and weeping willows. Additionally, they frequently include pavilions or landing stages, as is the case with the north pond.

Follies

The Countess de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers constructed several garden follies to enhance the park and mark the pathways. The estate features a stone garden bridge, a structure known as the guard's house, and the Monplaisir tower, which may have been designed by René Hodé. This tower, constructed in a neo-Gothic style similar to the castle, takes its name from the La Rochefoucauld motto, "C'est mon plaisir" (It is my pleasure). The ground floor of the tower may have been a garden room and secondary entrance, but its primary purpose was as a water tower, with a cistern located on the upper level. The bridge and ha-ha were designed by Louis Hodé, René's son, who may also have been the visionary behind the Monplaisir Tower.

Other follies were situated around the large pond to the north. The faux Gothic ruin at the entrance is still visible, simulating a construction vestige, likely religious, as a statue of the Madonna and Child stands on the side pillar. It now serves as the entrance to the municipal campsite. The pond also featured a dock and a pavilion, which was destroyed in 1979. The pavilion, known as the "pavilion on the water," was a square neo-Gothic structure constructed of iron and wood, surrounded by lancet arch openings. It was supported by a platform resting on six pilings, connected by additional lancet arches. The architect responsible for this structure remains unknown.

- Follies

-

Garden bridge.

Garden bridge.

-

Monplaisir Tower.

Monplaisir Tower.

-

Tower.

Tower.

-

Orangery.

Orangery.

-

Artificial ruin.

Artificial ruin.

-

The pavilion on the water at the beginning of the 20th century.

The pavilion on the water at the beginning of the 20th century.

Dependencies

The castle's extensive outbuilding was constructed between 1859 and 1860, replacing the previous service buildings located between the gatehouse and the castle. This large structure accommodates servants' quarters, stables, and carriage houses all under one roof. In line with the typical layout of 19th-century estates, it deviates from the castle's neo-Gothic style and instead features a Louis XIII's style with faux brick and stone facades.

Across the road is the estate's farm, known as the Lower Courtyard, which mirrors the style of the large outbuilding. Adjacent to it is the vegetable garden, complete with a small house for the gardeners. Originally intended to provide vegetables for the castle, the garden was entrusted to an association in 2005. It has been meticulously restored to its 19th-century design, using the original plans. Its layout forms a cross shape, representing the Anjou region, and showcases a variety of both old and modern plant species.

The castle features an orangery and a greenhouse in a garden adjacent to the presbytery, across from Étang Street. To prevent them from being isolated from the rest of the park, an underground passage was constructed beneath the street. The entrance to the passage, located in the basement of the Monplaisir tower, has been sealed off. The orangery, possibly designed by René Hodé, was constructed in the neo-Gothic style. Despite its Mouchette gallery and sculpted capitals, the building maintains an overall neoclassical structure. It comprises a rectangular main body with lowered arch openings.

The final element to be added to the property was the monumental entrance gatehouse, designed to resemble fortified medieval gates. It was completed in 1882. This structure reflects the desire of the 19th century to materialize the entrance to the domain.

Further reading

Bibliography

- Massin-Le Goff, Guy (2007). Les châteaux néo-gothiques en Anjou (in French). Paris: Nicolas Chaudin. ISBN 978-2-35039-032-1.

- Ribaud, Marc; Sart, Catherine; Guy (2007). Challain-la-Potherie (in French). Challain-la-Potherie: Mairie de Challain-la-Potherie. ISBN 978-2-7466-0128-4.

- Derouet, Christian (1977). L'œuvre de René Hodé, 1840-1870: architecture d'hier : grandes demeures angevines au XIXe siècle (in French). Paris: Caisse nationale des monuments historiques et des sites.

- de l'Esperonnière, René (1894). Histoire de la baronnie et du canton de Candé (PDF) (in French). Vol. 1. Angers: Lachèse. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2021.

- Steimer, Claire; Cussonneau, Christian; Pelloquet, Thierry (2009). Le pays segréen : patrimoine d'un territoire (Maine-et-Loire – Pays de la Loire). Images du Patrimoine (in French). Nantes: DRAC Pays de la Loire. ISBN 978-2-917895-02-3.

- Massin-Le Goff, Guy (1999). "Le néo-gothique civil en Anjou". 303, arts, recherches et créations (in French) (61): 40–49.

- Massin-Le Goff, Guy (2010). "En Anjou : étonnants châteaux néo-gothiques". Vieilles maisons françaises (in French) (233): 72–81.

- Poupard, Stéphanie (2007). "René Hodé, le maître d'œuvre du néo-gothique angevin". Demeure historique (in French) (166): 58–61.

- Cussonneau, Christian. Dossier de documentation, château de Challain-la-Potherie (in French). Inventaire général du Patrimoine culturel des Pays de la Loire.

Related articles

External links

- "Official website". Archived from the original on 23 February 2011.

- Architectural resource: Mérimée

References

Bibliographical sources

- Les châteaux néo-gothiques en Anjou

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 51

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 27

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 31

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 40

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 50

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 53

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 52

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 190

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 55

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 58

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 59

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 65

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 76

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 269

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 54

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 64

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 61

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 66

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 199

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 200

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 26

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 184

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 181

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 191

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 198

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 242

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 240

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 241

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 236

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 239

- Massin-Le Goff 2007, p. 237

- Le néo-gothique civil en Anjou

- Massin-Le Goff 1999, p. 41

- ^ Massin-Le Goff 1999, p. 42

- Massin-Le Goff 1999, p. 46

- Massin-Le Goff 1999, p. 48

- L'œuvre de René Hodé, 1840–1870: architecture d'hier: grandes demeures angevines au XIX siècle

- Derouet 1977, p. 3

- ^ Derouet 1977, p. 4

- ^ Derouet 1977, p. 6

- ^ Derouet 1977, p. 5

- ^ Derouet 1977, p. 21

- ^ Derouet 1977, p. 24

- ^ Derouet 1977, p. 14

- Derouet 1977, p. 16

- ^ Derouet 1977, p. 17

- Derouet 1977, p. 19

- ^ Derouet 1977, p. 7

- Derouet 1977, p. 8

- Dossier de documentation, château de Challain-la-Potherie

- ^ Cussonneau, p. 2

- Cussonneau, p. 167

- Cussonneau, p. 168

- Cussonneau, p. 34

- Cussonneau, p. 172

- Cussonneau, p. 175

- Le pays segréen: patrimoine d'un territoire (Maine-et-Loire – Pays de la Loire)

- ^ Steimer, Cussonneau & Pelloquet 2009, p. 140

- Steimer, Cussonneau & Pelloquet 2009, p. 141

- Histoire de la baronnie et du canton de Candé

- ^ de l'Esperonnière 1894, p. 453

- ^ de l'Esperonnière 1894, p. 416

- de l'Esperonnière 1894, p. 432

- de l'Esperonnière 1894, p. 437

- de l'Esperonnière 1894, p. 442

- de l'Esperonnière 1894, p. 447

- ^ de l'Esperonnière 1894, p. 452

Other references

- de Vaugondy, Robert (1768). Carte du gouvernement de Bretagne (in French).

- ^ Babelon, J. P (1995). Le château en France (in French). Berger-Levrault. p. 371. ISBN 270130668X.

- ^ Bordsen, John (17 April 2015). "Foreign Correspondence: Want to stay in a chateau? She owns one in France". Charlotte Observer. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Le château de Challain" (in French). Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Sarazin, André (2004). Supplément au dictionnaire historique, géographique et biographique de Maine-et-Loire de Célestin Port (in French). Mayenne: Régionales de l'Ouest. p. 211.

- "Rapport fait au nom de la commission d'enquête sur la situation financière, patrimoniale et fiscale des sectes, ainsi que sur leurs activités économiques et leurs relations avec les milieux économiques et financiers". National Assembly (in French). 10 June 1999. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- "L'argent caché des sectes". L'Express (in French). 19 September 1998. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Patrimoine à Challain. "En trois jours, nous avions acheté le château"". Ouest-France (in French). 4 September 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- "Château". Notice No. PA00109006, on the open heritage platform, Base Mérimée, French Ministry of Culture (in French).

- "Château". Notice No. PA49000100, on the open heritage platform, Base Mérimée, French Ministry of Culture (in French). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023.

- Massin-Le Goff, Guy (2005). "Châteaux et grandes demeures néo-gothiques en Anjou". Sociétés & Représentations (in French) (20): 134.

- "Château de Challain-la-Potherie". Maine-et-Loire tourist office (in French). Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- Babelon 1995, p. 376

- ^ Loyer, François (1983). Le siècle de l'industrie. 1789–1914 (in French). Geneva: Skira. p. 56. ISBN 2605000249.

- ^ Loyer 1983, p. 57

- ^ Babelon 1995, p. 377

- "Paul Mazaroz". Marc Maison (in French). Archived from the original on 6 June 2024. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- "Moulins". Notice No. IA49001617, on the open heritage platform, Base Mérimée, French Ministry of Culture (in French). Archived from the original on 6 June 2024.

- "Le potager du château (1 ha)". French Parks and Gardens Committee (in French). Archived from the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2019.