Climate change has serious effects on Russia's climate, including average temperatures and precipitation, as well as permafrost melting, more frequent wildfires, flooding and heatwaves. Changes may affect inland flash floods, more frequent coastal flooding and increased erosion reduced snow cover and glacier melting, and may ultimately lead to species losses and changes in ecosystem functioning.

Russia is part of the Paris Agreement that the rise in global average temperature should be kept way below 2 °C. Since Russia is the fourth-largest greenhouse gas emitter in the world, action is needed to reduce the impacts of climate change on both regional and global scale.

Greenhouse gas emissions

This section is an excerpt from Greenhouse gas emissions by Russia.Greenhouse gas emissions by Russia are mostly from fossil gas, oil and coal. Russia emits 2 or 3 billion tonnes CO2eq of greenhouse gases each year; about 4% of world emissions. Annual carbon dioxide emissions alone are about 12 tons per person, more than double the world average. Cutting greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore air pollution in Russia, would have health benefits greater than the cost. The country is the world's biggest methane emitter, and 4 billion dollars worth of methane was estimated to leak in 2019/20.

Russia's greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 30% between 1990 and 2018, excluding emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF). Russia's goal is to reach net zero by 2060, but its energy strategy to 2035 is mostly about burning more fossil fuels. Reporting military emissions is voluntary and, as of 2024, no data is available since before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.Impacts on the natural environment

Main article: Regional effects of global warmingTemperature and weather changes

According to IPCC (2007), climate change affected temperature increase which is greater at higher northern latitudes in many ways. For example, agricultural and forestry management at Northern Hemisphere higher latitudes, such as earlier spring planting of crops, higher frequency of wildfires, alterations in disturbance of forests due to pests, increased health risks due to heat-waves, changes in infectious diseases and allergenic pollen and changes to human activities in the Arctic, e.g. hunting and travel over snow and ice. From 1900 to 2005, precipitation increased in northern Europe and northern and central Asia. Recently these have resulted in fairly significant increases in GDP. Changes may affect inland flash floods, more frequent coastal flooding and increased erosion, reduced snow cover and species losses.

Past Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Russia for 1980-2016

Past Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Russia for 1980-2016 Predicted future Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Russia for 2071-2100 (scenario RCP8.5)

Predicted future Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Russia for 2071-2100 (scenario RCP8.5)

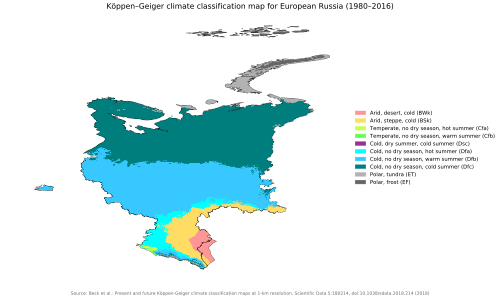

Past Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for European Russia for 1980-2016

Past Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for European Russia for 1980-2016 Predicted future Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for European Russia for 2071-2100 (scenario RCP8.5)

Predicted future Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for European Russia for 2071-2100 (scenario RCP8.5)

Current Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Asiatic Russia for 1980-2016

Current Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Asiatic Russia for 1980-2016 Predicted future Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Asiatic Russia for 2071-2100 (scenario RCP8.5)

Predicted future Köppen–Geiger climate classification map for Asiatic Russia for 2071-2100 (scenario RCP8.5)

Temperature changes until now

At present, the average annual temperature in the western regions of Russia rises by 0.4 – 0.5 °C every decade. This is due to both an increase in the number of warm days, and also a decrease in the number of cold days, since the 1970s. The occurrence of extremely hot days in the summer season has increased over the past 50 years, and the number of summer seasons with extremely hot days between 1980 and 2012 has doubled compared to the preceding three decades.

Over the last 100 years, the warming in Russia has been around 1.29 degrees Celsius, while warming on the global scale has been a, 0.74 degrees, according to the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, showing that the warming of the Russian climate is happening at a faster rate than average. In the Arctic, for example, temperatures are rising at double the rate of the global average, 0.2 degrees per decade over the past 30 years. The annual surface air temperature maxima and minima both increased, and the number of days with frost decreased over the last 100 years. The warming has been most evident in the winter and spring periods, and is more intense in the eastern part of the country, according to the Inter-Agency Commission of the Russian Federation on Climate Change, 2002. As a consequence, a lengthening of the vegetation period is seen across much of Russia, with the earlier onset of spring, and later beginning of autumn.

Precipitation changes until now

Patterns in precipitation changes are harder to identify, on average, increases in annual precipitation (7.2 mm/10 years) between 1976 and 2006 were observed in Russia in general. However, differing regional patterns have also been observed. A clear pattern is an increase in spring precipitation of 16.8mm per decade in Siberia and western parts of Russia, and a general decrease in precipitation in eastern regions.

Changes in snow cover and depth over the last 30 years show that snow cover decreased considerably in the western regions of Russia, as it did in the northern hemisphere in general. A general decrease in snow cover depth was also observed in western parts of the country. The main reason for this is the rise in temperatures. However, the increase in precipitation at higher latitudes has also led to an observed increase in snow accumulation in regions where winter temperatures remain cool enough.

Ice cover and glacier changes until now

Satellite observations of the changes in sea ice cover have shown a steady decrease in sea ice over the last 20 years, especially in the Arctic. The ice cover of rivers in the Baltic Sea drainage basin of Russia has also decreased over the last 50 years. The duration of river ice cover in the area decreased by between 25 and 40 days on average. Similarly, ice cover thickness has also decreased (by 15 – 20%) over the second half of the 20th century.

As a consequence of increasing temperatures and changing precipitation patterns, glaciers in Russia have been reduced by between 10 and 70% over the second part of the 20th century. The differences in rate of glacier changes depend on specific local climatic dynamics.

Projected temperature changes

Climate change is projected to lead to warming temperatures in most areas of the world, but in Russia this increase is expected to be even larger than the global average. By 2020, the average annual temperatures increased by around 1.1 °C compared to the 1980-1999 period, and temperatures are expected to continue rising, increasing by between 2.6 and 3.4 °C by 2050 (depending on the RCP model used). The rise in daily temperature minima is expected to be more dramatic than that of the daily temperature maxima, progressively decreasing the difference between the two. In addition, the number of days with frost is projected to decrease by between 10 and 30 days in different regions of the country, with the greatest decreases in the western parts of Russia (and in Eastern Europe). By 2100, average annual temperatures compared to the 1960-1990 period are expected to increase the most in the Arctic region, by around 5.5 °C. In central regions of the country, a slightly smaller increase of 4.5 - 5.5 °C is expected, and in southern and western regions, an increase between 3.5 and 4 °C.

Most projection models show that the most dramatic temperature increase is expected in winter average daily temperatures, especially in the western parts of the Russia (and in eastern Europe). This pronounced increase in winter temperatures is connected to the reduction of snow cover as a consequence of climate change. Less winter snow cover because of warmer temperatures leads to a reduced albedo effect. This results in less of the sun's radiation being reflected away from the earth, and more being absorbed by the ground, increasing surface air temperatures. Higher temperatures lead to even less snow cover, forming a positive feedback loop.

The Arctic, which forms a large part of the territory of Russia, is particularly vulnerable to climate change and is warming much more rapidly than the global average. See also: “Climate change in the Arctic”.

Climate change and the associated temperature increases will also heighten the intensity of heat waves in Russia. Extreme heat waves such as the one that hit Russia and eastern Europe in 2010 (the hottest summer in the last 500 years in this region) will become more likely, leading to an increase in the associated heat-related deaths and economic losses.

Projected precipitation changes

Most models and emission scenarios show, by the year 2100, the average annual precipitation is projected to increase over most of Russia as compared to the 1960-1990 period. The highest precipitation increases of >20% are expected in the northern regions of the country, with most other regions experiencing increases between 10 and 20%. Most of this increase is projected to be in winter precipitation. However, a decrease in precipitation is expected in the southern regions of Russia, especially in the south-west and Siberia.

Overall, climate change will lead to an important reduction in snow cover in most areas of Russia. The projected increase in winter precipitation in most parts of the country will be mainly due to rain, reducing the snow mass and increasing winter runoff. Meanwhile, in Siberia, the increased precipitation is expected to fall as snow, however this will lead to accumulation of snow mass in winter followed by rapid melting in the spring, increasing the risk of floods.

Projected ice cover and glacier changes

Most of the changes in ice cover brought on by climate change in Russia will happen in the Arctic. Compared to the 1910-1959 period, the area covered by ice in the Arctic is expected to continue to decrease during the 21st century, with the maximum ice extent (in March) decreasing by around 2% per decade, and the minimum ice extent (in September) decreasing by around 7% per decade. The breaking up of ice cover significantly endangers the habitat of polar bears as well as other Arctic species and the ecosystem as a whole. It may lead to an increase in iceberg occurrence as well as erosion of the coastline.

For more details about the specific impacts of climate change in the Arctic, please see the article “Climate Change in the Arctic”.

Permafrost

Further information: Permafrost § Effects of climate changePermafrost is soil which has been frozen for two or more years. In most Arctic areas it is from a few to several hundred metres thick. Permafrost thawing may be a serious cause for concern.

Thawing permafrost represents a threat to industrial infrastructure. In May 2020 thawing permafrost at Norilsk-Taimyr Energy's Thermal Power Plant No. 3 caused an oil storage tank to collapse, flooding local rivers with 21,000 cubic metres (17,500 tonnes) of diesel oil. The 2020 Norilsk oil spill has been described as the second-largest oil spill in modern Russian history.

Wildfires

IPCC show that higher temperatures may increase the frequency of wildfires. In Russia, this includes the risk of peatland fires. Peat fire emissions may be more harmful to human health than forest fires. According to Wetlands International the 2010 Russian wildfires were mainly 80–90% from dewatered peatlands. Dewatered bogs cause 6% of human global warming emissions. Moscow air was filled with peat fire emissions in July 2010 and regionally visibility was below 300 metres. However, recent peatland restoration efforts in the area of Moscow following the 2010 wildfires have decreased the risk of severe fires in the future.

Taiga

The taiga is a biome mainly consisting of coniferous forests (where pines, spruce and larch dominate the tree cover), that mainly ranges all the way from western to eastern parts of Russia. This enormous forest region acts as an important carbon sink able to accumulate and store carbon, which contributes to lower the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. Much of the carbon is stored in peatlands and wetlands.

Tundra

The tundra is a biome characterised by the absence of trees due to low temperatures and a short growing season. The vegetation in the tundra is instead composed of shrubs, sedges, mosses, lichens and grasses. Russia encompasses a large proportion of the Arctic tundra biome. The increases in temperature caused by climate change lead to longer and warmer growing periods in the tundra. This in turn leads to increased productivity of the tundra biome, which in the long run will likely cause northern boreal forests to invade the tundra, changing the ecosystem. Meanwhile, the southern distribution of boreal forests is likely to retreat northwards, due to increasing temperatures, drought stress, more forest fires and new insect species.

Impacts on people

Impacts on indigenous people

Further information: Climate change and indigenous peoplesClimate change has impacted the traditional lifestyle of the indigenous people of Russia's Far North. Around 2.5 million people live in the Arctic zone. The majority of Russia's indigenous people are located in the Arctic and Siberian regions.

People of Siberia and Far East territories have depended on climate for many centuries for herding and fishing. Due to frequent winter thaws, reindeer have more limited access to lichens because ice layers formed on the ground, threatening traditional reindeer herding of Sami and Nenet people. Researchers have noticed that even small climate changes affect the nomadic life of Nenets. Climate change has also provoked a reduction of marine animals, damaging traditional fisheries.

The Center for the Support of Indigenous Peoples of the North has noted that Russia lacks a program for calculating the possible impact of climate change on indigenous zones. Many environmental Indigenous and Environmental Movements have been declared as foreign agents by the Russian Federation.

Economic impacts

Climate change in Russia have been proven to show negative effects on the country's economy. The agricultural production of the country suffers economic losses due to its dependency on weather and climate factors. The overall yield of grain crops in Russia is expected to decrease by 17% by 2050, thereby affecting prices of agricultural products on the global market. By the year of 2030, prices of grain crops are estimated to rise significantly: 29% for wheat, 33% for rice and 47% for maize.

The droughts of 2010 and 2012 in Russia was followed by increased prices of rye, wheat and barley in the country, thus showing the vitality of climate factors on crop yields.

In addition to historical trends, recent climatic anomalies continue to underscore the vulnerability of Russian agriculture to extreme weather events. For instance, in May 2024, an unexpected frost hit key agricultural regions within the so-called black soil belt, including the Voronezh, Tambov, and Lipetsk regions. This unseasonal freeze damaged approximately 265,000 hectares of crops in Voronezh alone, leading to significant agricultural losses. Events like these not only affect local economies but also have broader implications for global markets. The damage from the frost led to a reduction in wheat harvest forecasts, pushing international wheat prices to their highest levels since August 2023.

Russia in a changing climate, produced by several scholars at major universities, said Russia focuses on the Ukrainian war and relies on oil and natural gas to fund that effort. The country may suffer from climate-related issues, but that is not its biggest concern during the war. Russia also uses the oil and gas wealth to pay for social welfare programs.

Health impacts

Further information: Effects of climate change on human healthClimate change has the potential to affect human health in several ways, both directly and indirectly, through for example, extreme heatwaves, fires, floods or insect-borne diseases.

The predicted increases in average annual temperatures in most parts of Russia, especially the western and south-western regions, imply more frequent extreme heatwaves and forest fires. For example, during the heatwave that affected western Russia in 2010, temperatures in Moscow reached 38.2 °C, the highest temperature since records began 130 years ago. In addition, during the heatwave there were 33 consecutive days of temperatures above 30 °C in the city, increasing the incidence of heat-related deaths and health problems, and leading to forest fires. The heatwave and wildfires of 2010 in Russia resulted in around 14,000 heat and air-pollution related deaths, as well as around 25% crop failure that year, more than 10,000 km of burned area and around 15 billion US dollars of economic losses. Throughout the 21st century, extreme heatwaves such as that of 2010 are likely to occur more often.

In consequence of the 2006, 2003 and 2010 heatwaves in Europe and Russia, the IPCC (2012) has outlined mitigation strategies, including approaches to reduce impacts on public health, assessing heat mortality, communication of risk, education and adapting urban infrastructure to better withstand heatwaves (by for example increasing vegetation cover in cities, increasing albedo in cities and increasing insulation of homes).

With changes in temperature and precipitation patterns as a result of climate change, the distribution and occurrence of various disease-bearing insects will also change. For example, mosquitos carrying malaria are expected to pose an increasing threat in Russia in the 21st century. In the Moscow region, the onset of higher average daily temperatures early on in the year has already led to a rapid increase in malaria cases. This trend is projected to continue, as higher average temperatures extend the range of mosquitos northwards. Similarly, prevalence of tick-borne diseases is also projected to increase in Russia in the 21st century, as a result of climate change and changing distribution range of ticks. Sandfly-borne diseases, such as Leishmaniasis, could also expand in Europe and Russia as a result of climate change and increased average temperatures making transmission suitable in northern latitudes.

Floods may also pose and increased risk as a result of climate change in the 21st century. An average increase in precipitation in many areas of Russia as well as rapid snow and glacier melting due to rising temperatures, can all increase the risk of flooding.

Mitigation and adaptation

See also: Greenhouse gas emissions by Russia § MitigationApproaches

Russia has signed these international agreements to adapt to the climate change:

- Kyoto Protocol was ratified in 2009 by Russia, It came in force on 16 February 2010 The Kyoto protocol was ongoing in 2008–2012. The Russian federation target for GHG emissions for the period 2008-2012 was 0% changes in emissions from the base year (1990) and the result was -36.3%. The Kyoto agreement did not cause emission cuts for Russia due to an earlier drop in emissions compared to year 1990 for other reasons, mainly a significant drop in economic growth (→ History of Russia).

Six G8 countries would have been ready for the agreement to "at least halve global CO2 emissions by 2050" in 2007. Russia and the United States (Bush government) did not agree.

- Paris Agreement, in 2019 Russia announced that the 2015 Paris Agreement will be implemented

Policies and legislation

Further information: Climate Doctrine of the Russian FederationParis Agreement

The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international agreement, its main goal is to limit global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC's) are the plans to fight climate change adapted for each country. Every party to the agreement has different targets based on its own historical climate records and country's circumstances and all the targets for each country are stated in their NDC.

Some of the NDC targets of Russia against climate change and greenhouse gas emissions under the Paris Agreement are the following:

- 70% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions until 2030 relative to 1990, accounting for absorptive capacity of forest, ecosystems and social economical development.

- Voluntary support for developing countries to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Every country has different ways to achieve the established goals depending on resources. In the case of Russia the following approach is established to support the NDC's climate change plan:

- Use the maximum possible absorption capacity forests when counting the greenhouse gas emissions reduction. Partly to show the importance of greenhouse gas sinks and the need to protect and improving of them.

- Proactive work to aim to reducing the risk of climate change (for example construction of dams against floods).

- Emergency adaptation to minimize the damage in case of a climate change emergency

- Increasing energy efficiency in all sectors of the economy and developing the use of non-fuel and renewable energy sources.

- The Government of the Russian Federation approved an action plan to improve the energy efficiency of the Russian economy in 2019.

- Inventory of greenhouse gas emissions by monitoring, reporting and verification system

- Russia Federation will assist developing countries in achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement. This is done by increasing the peaceful use of nuclear energy in developing countries.

Progress

The goal of 70% emission reduction indicate an increasing ambition compared to earlier commitments to limit greenhouse gas emissions. In the Kyoto protocol Russia established indicator for limiting greenhouse gas emissions to no more than 75% of the 1990 level. The EU have instead the indicator to a 100%.

Climate action tracker (CAT), is an independent scientific analysis that tracks government climate action and measures it against the globally agreed Paris Agreement. Climate action tracker found Russian actions to be "critical insufficient". Data is scarce and out of date.

Society and culture

Environmental activism is a growing movement in Russia and it has developed into different shapes and forms, such as campaigns aiming to tackle both local and regional problems but also to address concerns including pollution, expansion of industries, non-sustainable forestry and further on. Around half of the Russian population (56%) lacks trust towards the country's agencies when it comes to environmental matters and 35% of the population are willing to take part of environmental protests.

See also

- Climate Doctrine of the Russian Federation – Russian policy on climate change

- Climate of Russia

- Coal in Russia – Coal use and production in Russia

- Drunken trees – Stand of trees displaced from their normal vertical alignment

- Energy in Russia

- Energy policy of Russia

- Environmental issues in Russia

- Hydroelectricity in Russia

- Northern Sea Route – Shipping route running along the Russian Arctic coast

- Plug-in electric vehicles in Russia

- Protected areas of Russia

- Renewable energy in Russia

References

- ^ IPCC Working group III fourth assessment report, Summary for Policymakers 2007

- "Historical GHG Emissions". Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- Joint Research Centre (European Commission); Olivier, J. G. J.; Guizzardi, D.; Schaaf, E.; Solazzo, E.; Crippa, M.; Vignati, E.; Banja, M.; Muntean, M. (2021). GHG emissions of all world: 2021 report. LU: Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2760/173513. ISBN 978-92-76-41546-6.

- "CO2 Emissions: Russia - 2021 - Climate TRACE". climatetrace.org. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- "BROWN TO GREEN: THE G20 TRANSITION TO A LOW-CARBON ECONOMY | 2017" (PDF). Climate Transparency.

- "Report: China emissions exceed all developed nations combined". BBC News. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo (11 May 2020). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- Sampedro, Jon; Smith, Steven J.; Arto, Iñaki; González-Eguino, Mikel; Markandya, Anil; Mulvaney, Kathleen M.; Pizarro-Irizar, Cristina; Van Dingenen, Rita (1 March 2020). "Health co-benefits and mitigation costs as per the Paris Agreement under different technological pathways for energy supply". Environment International. 136: 105513. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2020.105513. hdl:10810/44202. ISSN 0160-4120. PMID 32006762.

- Rust, Susanne; Times, Los Angeles. "How badly will Russia's war torpedo hopes for global climate cooperation?". phys.org. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Satellites map huge methane plumes from oil and gas". BBC News. 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Report on the technical review of the fourth biennial report of the Russian Federation" (PDF).

- "Nationally determined contribution of the Russian Federation" (PDF).

- "Does Russia have a climate plan to reduce carbon emissions?". euronews. 18 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "The Military Emissions Gap – Tracking the long war that militaries are waging on the climate". Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- Agafonova, S. A.; Frolova, N. L.; Krylenko, I. N.; Sazonov, A. A.; Golovlyov, P. P. (August 2017). "Dangerous ice phenomena on the lowland rivers of European Russia". Natural Hazards. 88 (S1): 171–188. doi:10.1007/s11069-016-2580-x. ISSN 0921-030X. S2CID 132534507.

- ^ "Climate change in Russia". Climatechangepost.com. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- "AR4 Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report — IPCC". Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- Institute, Joint Global Change Research; Division, Battelle Memorial Institute Pacific Northwest (31 March 2009). "Russia: Impact of Climate Change to 2030: A Commissioned Research Report". Homeland Security Digital Library. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Mokhov, I. I. (30 September 2008). "Possible regional consequences of global climate changes". Russian Journal of Earth Sciences. 10 (5): 1–6. doi:10.2205/2007ES000228. ISSN 1681-1208.

- ^ "Climate". meteoinfo.ru. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- Bednorz, E; Kossowski, T (2004). "Long-term changes in snow cover depth in eastern Europe". Climate Research. 27: 231–236. Bibcode:2004ClRes..27..231B. doi:10.3354/cr027231. ISSN 0936-577X.

- Khromova, Tatiana; Nosenko, Gennady; Nikitin, Stanislav; Muraviev, Anton; Popova, Valeria; Chernova, Ludmila; Kidyaeva, Vera (June 2019). "Changes in the mountain glaciers of continental Russia during the twentieth to twenty-first centuries". Regional Environmental Change. 19 (5): 1229–1247. doi:10.1007/s10113-018-1446-z. ISSN 1436-3798. S2CID 159406556.

- ^ Folland, Chris K.; Boucher, Olivier; Colman, Andrew; Parker, David E. (June 2018). "Causes of irregularities in trends of global mean surface temperature since the late 19th century". Science Advances. 4 (6): eaao5297. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.5297F. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao5297. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5990305. PMID 29881771.

- Kjellström, Erik (June 2004). "Recent and Future Signatures of Climate Change in Europe". Ambio: A Journal of the Human Environment. 33 (4): 193–198. doi:10.1579/0044-7447-33.4.193. ISSN 0044-7447. PMID 15264597. S2CID 2077991.

- Hauser, Mathias; Orth, René; Seneviratne, Sonia I. (28 March 2016). "Role of soil moisture versus recent climate change for the 2010 heat wave in western Russia". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (6): 2819–2826. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..43.2819H. doi:10.1002/2016GL068036. hdl:21.11116/0000-0006-B1D0-6. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 131602578.

- Hrsg., Leshkevich, N. V. (2008). Assessment report on climate change and its consequences in Russian Federation : general summary. OCLC 837042079.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Diesel fuel spill in Norilsk in Russia's Arctic contained". TASS. Moscow, Russia. 5 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Max Seddon (4 June 2020), "Siberia fuel spill threatens Moscow's Arctic ambitions", Financial Times

- Ivan Nechepurenko (5 June 2020), "Russia Declares Emergency After Arctic Oil Spill", The New York Times

- turvesuot liekeissä talveen asti yle 12.8.2010

- Venäjän metsäpalot tukaloittavat moskovalaisten elämää yle 26 July 2010

- Sirin, A.A.; Medvedeva, M.A.; Makarov, D.A.; Maslov, A.A.; Joosten, H. (December 2020). "Multispectral satellite based monitoring of land cover change and associated fire reduction after large-scale peatland rewetting following the 2010 peat fires in Moscow Region (Russia)". Ecological Engineering. 158: 106044. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2020.106044.

- Seppälä, Risto (30 November 2009). "A global assessment on adaptation of forests to climate change". Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research. 24 (6): 469–472. doi:10.1080/02827580903378626. ISSN 0282-7581. S2CID 83806885.

- ^ Stambler, Maria (31 August 2020). "The Impact of Climate Change on Indigenous Peoples Has Received Little Attention in Russia". Climate Scorecard. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Reindeer and their nomadic herders face climate change | DW | 04.08.2020". Welle (www.dw.com). Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Scollon, Michael (28 November 2020). "At Risk: Russia's Indigenous Peoples Sound Alarm On Loss Of Arctic, Traditional Way Of Life". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. RadioFreeEurope. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Economic analysis of the impact of climate change on agriculture in Russia" (PDF).

- "Extreme Weather Events and Crop Price Spikes in a Changing Climate: Illustrative global simulation scenarios".

- "Economic analysis of the impact of climate change on agriculture in Russia" (PDF).

- "Russia Crops Flip From Heat to Frost, Damaging Fields Further". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- "Russia in a changing climate". Wiley.

- ^ "Health in Russia". Climatechangepost.com. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- Barriopedro, D.; Fischer, E. M.; Luterbacher, J.; Trigo, R. M.; Garcia-Herrera, R. (8 April 2011). "The Hot Summer of 2010: Redrawing the Temperature Record Map of Europe". Science. 332 (6026): 220–224. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..220B. doi:10.1126/science.1201224. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21415316. S2CID 24947372.

- Shaposhnikov, Dmitry; Revich, Boris; Bellander, Tom; Bedada, Getahun Bero; Bottai, Matteo; Kharkova, Tatyana; Kvasha, Ekaterina; Lezina, Elena; Lind, Tomas; Semutnikova, Eugenia; Pershagen, Göran (May 2014). "Mortality Related to Air Pollution with the Moscow Heat Wave and Wildfire of 2010". Epidemiology. 25 (3): 359–364. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000000090. ISSN 1044-3983. PMC 3984022. PMID 24598414.

- Field, Christopher B.; Barros, Vicente; Stocker, Thomas F.; Dahe, Qin, eds. (18 September 2018), "IPCC, 2012: Summary for Policymakers", Planning for Climate Change, Routledge, pp. 111–128, doi:10.4324/9781351201117-15, ISBN 978-1-351-20111-7, S2CID 240164028, retrieved 19 May 2021

- Human development report 2007/2008 : fighting climate change : human solidarity in a divided world. United Nations Development Programme. New York: United Nations Development Programme. 2007. ISBN 978-0-230-54704-9. OCLC 187311028.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Karaman, Ana (17 April 2018), "Russia and global climate change", Climate Change, Policy and Security, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, pp. 216–234, doi:10.4324/9781351060479-10, ISBN 978-1-351-06047-9, retrieved 19 May 2021

- Semenza, Jan C; Menne, Bettina (June 2009). "Climate change and infectious diseases in Europe". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 9 (6): 365–375. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70104-5. PMID 19467476.

- "ENTRY INTO FORCE OF KYOTO PROTOCOL, FOLLOWING RUSSIA'S RATIFICATION, HISTORIC STEP FORWARD TO COMBAT GLOBAL WARMING, SECRETARY-GENERAL SAYS IN NAIROBI | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". www.un.org. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Shishlov, Igor; Morel, Romain; Bellassen, Valentin (17 August 2016). "Compliance of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol in the first commitment period". Climate Policy. 16 (6): 768–782. doi:10.1080/14693062.2016.1164658. ISSN 1469-3062. S2CID 156120010.

- Afghanistan's environment 2008 / United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Afghanistan Centre at Kabul University. 2008. doi:10.29171/azu_acku_pamphlet_ge320_a33_a333_2008.

- "Russia gives definitive approval to Paris climate accord". Reuters. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- "The Paris Agreement". unfccc.int. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- "NDC spotlight". unfccc.int. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- "Nationally Determined Contributions". unfccc.int. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Gyanchandani, Vandana (2016). "UNFCCC Nationally Determined Contributions: Climate Change and Trade". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3286257. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 219337488.

- "NDC submission by Russia". unfccc.int. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Heaney, Dominic (13 May 2021), "Chronology of Russia", The Territories of the Russian Federation 2021, Routledge, pp. 16–33, doi:10.4324/9781003143864-2, ISBN 978-1-003-14386-4, retrieved 24 May 2021

- "Air and climate: Greenhouse gas emissions by source (Edition 2019)". OECD Environment Statistics. 17 November 2017. doi:10.1787/ff19698d-en. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- "Половина россиян считает, что экологическая ситуация в России за последние годы ухудшилась".

| Climate change by country | |

|---|---|

| Greenhouse gas emissions, impacts, mitigation and adaptation in each country | |

| Africa | |

| Americas | |

| Asia | |

| Europe | |

| Oceania | |

| Polar regions | |

| Other regions | |

| Energy in Russia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topics | |||||||||

| Sources | |||||||||

| Electricity generation | |||||||||

| Energy companies | |||||||||

| Politics and disputes (before 2022 invasion) |

| ||||||||

| Ukraine invasion and sanctions | |||||||||