A spa is a location where mineral-rich spring water (sometimes seawater) is used to give medicinal baths. Spa health treatments are known as balneotherapy. The belief in the curative powers of mineral waters and hot springs goes back to prehistoric times. Spa towns, spa resorts, and day spas are popular worldwide, but are especially widespread in Europe and Japan.

Etymology

See also: Mineral spa

The term is derived from the town of Spa, Belgium, whose name in Roman times was Aquae Spadanae. The term is sometimes incorrectly attributed to the Latin word spargere, meaning to scatter, sprinkle, or moisten.

During the medieval era, illnesses caused by iron deficiency were treated by drinking chalybeate. In 1326, ironmaster Collin le Loup discovered the treatment. The water was sourced from a spring called Espa, the Walloon word for "fountain".

In 16th-century England, the old Roman ideas of medicinal bathing were revived in towns like Bath (named for its Roman baths). In 1596, William Slingsby, who had been to Spa, Belgium (which he called Spaw), discovered a chalybeate spring in Yorkshire. He built an enclosed well at what became known as Harrogate, the first resort in England for drinking medicinal waters. In 1596, Timothy Bright, after discovering a second well, called the resort The English Spaw, beginning the use of the word Spa as a generic description.

It is commonly claimed, in a commercial context, that the word is an acronym of various Latin phrases, such as salus per aquam or sanitas per aquam, meaning "health through water". The derivation does not appear before the early 21st century. It is likely a backronym as it does not match the known Roman name for the location.

History

Spa therapies have existed since the classical times when taking bath with water was considered as a popular means to treat illnesses. The practice of travelling to hot or cold springs for medicinal purposes dates back to prehistoric times. Archaeological investigations near hot springs in France and Czech Republic revealed Bronze Age weapons and offerings.

Many people around the world believed that bathing in a particular spring, well, or river resulted in physical and spiritual purification. Forms of ritual purification existed among the Arabs, Persians, Ottoman Turks, Native Americans, Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. Today, ritual purification through water can be found in the religious ceremonies of Muslims, Jews, Christians, Buddhists, and Hindus. These ceremonies reflect the ancient belief in the healing and purifying properties of water. Complex bathing rituals were also practiced in ancient Egypt, in prehistoric cities of the Indus Valley, and in Aegean civilizations. Typically, people did little construction around the water, and what was constructed was temporary.

Bathing in Greek and Roman times

Some of the earliest descriptions of western bathing practices came from Greece. The Greeks began bathing regimens that formed the foundation for modern spa procedures. Aegean people utilized small bathtubs, wash basins, and foot baths for personal cleanliness. The earliest such findings are the baths in the palace complex at Knossos, Crete, and the alabaster bathtubs excavated in Akrotiri, Santorini; both date from the mid-2nd millennium BC. They established public baths and showers within their gymnasium complexes for relaxation and personal hygiene. Greek mythology specified that certain natural springs or tidal pools were blessed by the gods to cure disease. Around these sacred pools, Greeks established bathing facilities for those desiring healing. Supplicants left offerings to the gods for healing at these sites and bathed themselves in hopes of a cure. The Spartans developed a primitive vapor bath. At Serangeum, an early Greek balneum (bathhouse, loosely translated), bathing chambers were cut into the hillside from which the hot springs issued. A series of niches cut into the rock above the chambers held bathers' clothing. One of the bathing chambers had a decorative mosaic floor depicting a driver and chariot pulled by four horses, a woman followed by two dogs, and a dolphin below. Thus, the early Greeks used the natural features, but expanded them and added their own amenities, such as decorations and shelves. During later Greek civilization, bathhouses were often built in conjunction with athletic fields.

Main article: Ancient Roman bathingThe Romans emulated many of the Greek bathing practices. Romans surpassed the Greeks in the size and complexity of their baths, due to the larger size and population of Roman cities, the availability of running water following the building of aqueducts, and the invention of cement, which made building large edifices easier, safer, and cheaper. As in Greece, the Roman bath became a focal center for social and recreational activity. As the Roman Empire expanded, the concept of the public bath spread to all parts of the Mediterranean and into regions of Europe and North Africa. With the construction of the aqueducts, the Romans had enough water not only for domestic, agricultural, and industrial uses, but also for leisurely pursuits. The aqueducts provided water that was later heated for use in the baths. Today, the extent of the Roman bath is found at ruins and in archaeological excavations in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

The Romans also developed baths in their colonies, taking advantage of the natural hot springs occurring in Europe to construct baths at Aix and Vichy in France, Bath and Buxton in England, Aachen and Wiesbaden in Germany, Baden, Austria, and Aquincum in Hungary, among other locations. These baths became centers for recreational and social activities in Roman communities. Libraries, lecture halls, gymnasiums, and formal gardens became part of some bath complexes. In addition, the Romans used the hot thermal waters to relieve their suffering from rheumatism, arthritis, and overindulgence in food and drink. The decline of the Roman Empire in the west, beginning in AD 337 after the death of Emperor Constantine, resulted in Roman legions abandoning their outlying provinces and leaving the baths to be taken over by the local population or destroyed.

The Roman bathing ritual included undressing, bathing, sweating, receiving a massage, and resting. Each procedure required separated, purpose-built rooms. The segregation of the sexes and the additions of diversions not directly related to bathing also had direct impacts on the shape and form of bathhouses. The elaborate Roman bathing ritual and its resultant architecture served as precedents for later European and American bathing facilities. Formal garden spaces and opulent architectural arrangement equal to those of the Romans reappeared in Europe by the end of the 18th century. Major American spas followed suit a century later.

Bathing in medieval times

With the decline of the Roman Empire, the public baths often became places of licentious behavior, and such use was responsible for the spread rather than the cure of diseases. A general belief developed among the European populace was that frequent bathing promoted disease and sickness. Medieval church authorities encouraged this belief and made every effort to close down public baths. Ecclesiastical officials believed that public bathing created an environment open to immorality and disease. Roman Catholic Church officials even banned public bathing in an unsuccessful effort to halt syphilis epidemics from sweeping Europe. Overall, this period represented a time of decline for public bathing.

People continued to seek out a few select hot and cold springs, believed to be holy wells, to cure various ailments. In an age of religious fervor, the benefits of the water were attributed to God or one of the saints. In 1326, Collin le Loup, an ironmaster from Liège, Belgium, discovered the chalybeate springs of Spa, Belgium. Around these springs, a famous health resort eventually grew and the term "spa" came to refer to any health resort located near natural springs. During this period, individual springs became associated with the specific ailment that they could allegedly benefit.

Great bathhouses were built in Byzantine centers such as Constantinople and Antioch, and the popes allocated to the Romans bathing through diaconia, or private Lateran baths, or even a myriad of monastic bath houses functioning in the eighth and ninth centuries. The Popes maintained baths in their residences, and bath houses known as "charity baths" as they served both the clerics and the poor incorporated into Christian Church buildings or those of monasteries. The Church also built public bathing facilities that were separate for both sexes near monasteries and pilgrimage sites. Popes situated baths within church basilicas and monasteries since the early Middle Ages. Catholic religious orders of the Augustinians' and Benedictines' rules contained ritual purification. Benedictine monks played a role in the development and promotion of the spa, inspired by Benedict of Nursia's encouragement for the practice of therapeutic bathing. Protestantism also played a prominent role in the development of the British spas. Public bathing and spas were common in medieval Christendom in larger towns and cities such as Paris, Regensburg, and Naples.

Bathing procedures during this period varied greatly. In the 16th century, physicians at Karlsbad, Bohemia, prescribed mineral water to be taken internally as well as externally. Patients periodically bathed in warm water for up to 10 or 11 hours while drinking glasses of mineral water. The first bath session occurred in the morning, and the second in the afternoon. This treatment lasted several days until skin pustules formed and broke resulting in the draining of "poisons" considered to be the source of the disease. This was followed by a series of shorter, hotter baths to wash the infection away and close the eruptions.

In the English coastal town of Scarborough in 1626, Elizabeth Farrow discovered a stream of acidic water running from one of the cliffs to the south of the town. This was deemed to have beneficial health properties and gave birth to Scarborough Spa. Dr Wittie's book about the spa waters, published in 1660, attracted a flood of visitors to the town. Sea bathing was added to the cure, and Scarborough became Britain's first seaside resort. The first rolling bathing machines for bathers are recorded on the sands in 1735.

Bathing in the 18th century

In the 17th century, most upper-class Europeans washed their clothes with water and washed only their faces with linen, feeling that bathing the entire body was a lower-class activity. The upper-class slowly began changing their attitudes toward bathing as a way to restore health later that century. The wealthy flocked to health resorts to drink and bathe in the waters. In 1702, Anne, Queen of Great Britain, travelled to Bath. A short time later, Beau Nash came to Bath, and along with financier Ralph Allen and architect John Wood, transformed Bath from a country spa into the social capital of England. Bath set the tone for other spas in Europe to follow. The upper class arrived there on a seasonal basis to bathe in and drink the water, and as a show of status. Social activities at Bath included dances, concerts, playing cards, lectures, and promenading down the street.

A typical day at Bath consisted of an early morning communal bath followed by a private breakfast party. Afterwards, one either drank water at the Pump Room (a building constructed over the thermal water source) or attended a fashion show. Physicians encouraged health resort patrons to both bathe in and drink the waters. The next several hours of the day could be spent in shopping, visiting the lending library, attending concerts, or stopping at one of the coffeehouses. At 4:00 pm, the wealthy dressed up in their finery and promenaded down the streets. Next came dinner, more promenading, and an evening of dancing or gambling.

Similar activities occurred in health resorts throughout Europe. The spas became stages on which Europeans paraded with great pageantry. These resorts became infamous as places full of gossip and scandals. The various social and economic classes selected specific seasons during the year's course, staying from one to several months, to vacation at each resort. One season aristocrats occupied the resorts; at other times, prosperous farmers or retired military men took the baths. The wealthy and the criminals that preyed on them moved from one spa to the next as the fashionable season for that resort changed.

During the 18th century, a revival in the medical uses of spring water was promoted by Enlightened physicians across Europe. This revival changed the way of taking a spa treatment. For example, in Karlsbad the accepted method of drinking the mineral water required sending large barrels to individual boardinghouses where the patients drank physician-prescribed dosages in the solitude of their rooms. David Beecher in 1777 recommended that the patients come to the fountainhead for the water and that each patient should first do some prescribed exercises. This innovation increased the medicinal benefits obtained and gradually physical activity became part of the European bathing regimen. In 1797, in England, James Currie published The Effects of Water, Cold and Warm, as a Remedy in Fever and other Diseases.This book, along with numerous local pamphlets on composition of spa water, stimulated additional interest in water cures and advocated the external and internal use of water as part of the curing process.

Bathing in the 19th and 20th centuries

In the 19th century, bathing became a more accepted practice as physicians realized some of the benefits that cleanliness could provide. A cholera epidemic in Liverpool, England in 1842 resulted in a sanitation renaissance, facilitated by the overlapping hydropathy and sanitation movements, and the implementation of a series of statutes known collectively as "The Baths and Wash-houses Acts 1846 to 1896". The result was increased facilities for bathing and washed clothes, and more people participating in these activities.

In most instances, the formal architectural development of European spas took place in the 18th and 19th centuries. The architecture of Bath, England, developed along Georgian and Neoclassical lines, generally following Palladian structures. The most important architectural form that emerged was the "crescent" — a semi-elliptical street plan used in many areas of England. The spa architecture of Carlsbad, Marienbad, Franzensbad, and Baden-Baden was primarily Neoclassical, but the literature seems to indicate that large bathhouses were not constructed until well into the 19th century. The emphasis on drinking the waters rather than bathing in them led to the development of separate structures known as Trinkhallen (drinking halls) where those taking the cure spent hours drinking water from the springs.

In Southeastern Europe, development of spa resorts took place mostly in the second half of the 19th century, such as the Slatina Spa in the Republic of Srpska, BiH, where the thermal and healing springs were discovered in the Roman times. Development of the spa resort in Slatina began in the 1870s, when the first modern spa facilities were built.

By the mid-19th century, visitors to the European spas began to emphasise bathing in addition to drinking the waters. Besides fountains, pavilions, and Trinkhallen, bathhouses on the scale of the Roman baths were revived. Photographs of a 19th-century spa complex taken in the 1930s, detailing the earlier architecture, show heavy use of mosaic floors, marble walls, classical statuary, arched openings, domed ceilings, segmental arches, triangular pediments, Corinthian columns, and all the other trappings of a Neoclassical revival. The buildings were usually separated by function — with the Trinkhalle, the bathhouse, the inhalatorium (for inhaling the vapors), and the Kurhaus or Conversationhaus as the center of social activity. Baden-Baden featured golf courses and tennis courts, "superb roads to motor over, and drives along quaint lanes where wild deer are as common as cows to us, and almost as unafraid".

The European spa started with structures to house the drinking function, such as simple fountains, pavilions, and elaborate Trinkhallen. Enormous bathhouses came later in the 19th century as a renewed preference for an elaborate bathing ritual to cure ills and improve health became popular. European architects looked back to Roman civilizations and emulated their architecture. Europeans copied the same formality, symmetry, division of rooms by function, and opulent interior design in their bathhouses. They emulated the fountains and formal garden spaces in their resorts, and added new diversions. Tour books of the time mentioned the roomy, woodsy offerings in the vicinity and the faster-paced evening diversions.

By the beginning of the 19th century, the European bathing regimen consisted of numerous accumulated traditions. The bathing routine included soaking in hot water, drinking the water, steaming in a vapor room, and relaxing in a cooling room. In addition, doctors ordered that patients be douched with hot or cold water and given curative diets. Authors began writing guidebooks to the health resorts of Europe explaining the medical benefits and social amenities, inspiring rich Europeans and Americans to travel to these resorts.

Each European spa began offering similar cures while maintaining a certain amount of individuality. The 19th-century bathing regimen at Karlsbad consisted of visitors arising at 6 am to drink the water and be serenaded by a band. Next came a light breakfast, bath, and lunch. The doctors at Karlsbad usually limited patients to certain foods for each meal. In the afternoon, visitors went sight-seeing or attended concerts. Nightly theatrical performances followed the evening meal. This ended around 9 pm with the patients returning to their boardinghouses to sleep until 6 the next morning. This regimen continued for as long as a month and then the patients returned home until the next year. Other 19th-century European spa regimens followed similar schedules.

At the beginning of the 20th century, European spas combined a strict diet and exercise regimen with a complex bathing procedure. Patients at Baden-Baden, which specialized in treating rheumatoid arthritis, were directed to see a doctor before taking the baths. Bathers then proceeded to the main bathhouse where they paid for their baths and stored their valuables before being assigned a booth for undressing. The bathhouse supplied bathers with towels, sheets, and slippers.

The Baden-Baden bathing procedure began with a warm shower. The bathers next entered a room of circulating, 140 °F (60 °C) hot air for 20 minutes, spent another ten minutes in a room with 150 °F (66 °C) temperature, partook of a 154 °F (68 °C) vapor bath, then showered and received a soap massage. After the massage, the bathers swam in a pool heated approximately to body temperature. After the swim, the bathers rested for 15 to 20 minutes in the warm "Sprudel" room pool. This shallow pool's bottom contained an 8-inch (200 mm) layer of sand through which naturally carbonated water bubbled up. This was followed by a series of gradually cooler showers and pools. After that, the attendants rubbed down the bathers with warm towels and then wrapped them in sheets and covered them with blankets to rest for 20 minutes. The rest of the treatment consisted of a prescribed diet, exercise, and water-drinking program.

European spas provided various other diversions for guests after the bath, including gambling, horse racing, fishing, hunting, tennis, skating, dancing, golf, sight-seeing, theatrical performances, and horseback riding. Some European governments recognized the medical benefits of spa therapy and paid a portion of the patient's expenses. A number of these spas catered to those suffering from obesity and overindulgence in addition to various other medical complaints. In recent years, people still travel to natural hot springs for relaxation and health.

In Germany, the tradition survives to the present day. 'Taking a cure' (Kur) at a spa is generally largely covered by both public and private health care insurance. Usually, a doctor prescribes a stay of three weeks at a mineral spring or other natural setting where a patient's condition will be treated with healing spring waters and natural therapies. While insurance companies used to cover meals and accommodation, many now only pay for treatments and expect the patient to pay for transportation, accommodation, and meals. Most Germans are eligible for a Kur every two to six years, depending on the severity of their condition. Germans get paid their regular salary during this time away from their job, which is not taken out of their vacation days.

Bathing in colonial America

Some European colonists brought with them knowledge of the hot water therapy for medicinal purposes, and others learned the benefits of hot springs from Native Americans. Europeans stole the land on which many of the hot and cold springs were situated from various tribes, and altered them to suit European tastes. By the 1760s, British colonists were traveling to hot and cold springs in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, New York, and Virginia in search of water cures. Among the more frequently visited of these springs were Bath, Yellow, and Bristol Springs in Pennsylvania; and Warm Springs, Hot Springs, and White Sulphur Springs in West Virginia. In the 1790s, New York spas were beginning to be frequented, most notably Ballston Spa. Nearby Saratoga Springs and Kinderhook were yet to be discovered.

Colonial doctors gradually began to recommend hot springs for ailments. Benjamin Rush, American patriot and physician, praised the springs of Bristol, Pennsylvania, in 1773. Samuel Tenney in 1783 and Valentine Seaman in 1792 examined the water of Ballston Spa in New York and wrote of possible medicinal uses of the springs. Hotels were constructed to accommodate visitors to the various springs. Entrepreneurs operated establishments where the travellers could lodge, eat, and drink.

Bathing in 19th- and 20th-century America

After the American Revolution, the spa industry continued to gain popularity. The first truly popular spa was Saratoga Springs, which, by 1815, had two large, four-story, Greek revival hotels. It grew rapidly, and by 1821 it had at least five hundred rooms for accommodation. Its relative proximity to New York City and access to the country's most developed steamboat lines meant that by the mid-1820s the spa became the country's most popular tourist destination, serving both the country's elite and the middle classes. Although spa activity had been central to Saratoga in the 1810s, by the 1820s the resort had hotels with great ballrooms, opera houses, stores, and clubhouses.

The Union Hotel, first built in 1803, had its own esplanade, and by the 1820s had its own fountain and formal landscaping, but with only two small bathhouses. As the resort developed as a tourist destination, mineral bathhouses became auxiliary structures and not the central features of the resort, although the drinking of mineral water continued to be common. Although the purpose of the Saratoga and other New York spas were to provide access to mineral waters, their main attraction was a complex social life and cultural cachet. However, the wider audience the resort garnered by the late 1820s began to waver, and in the mid-1830s, as a bid to revive itself, it turned to horse racing.

By the mid-1850s hot and cold spring resorts existed in 20 states. Many of these resorts contained similar architectural features. Most health resorts had a large, two-story central building near or at the springs, with smaller structures surrounding it. The main building provided the guests with facilities for dining, dancing on the first floor, and sleeping rooms on the second. The outlying structures were individual guest cabins, and other auxiliary buildings formed a semicircle or U-shape around the large building.

These resorts offered swimming, fishing, hunting, and horseback riding as well as facilities for bathing. The Virginia resorts, particularly White Sulphur Springs, proved popular before and after the Civil War. After the Civil War, spa vacations became very popular as returning soldiers bathed to heal wounds and the American economy allowed more leisure time. Saratoga Springs in New York became one of the main centers for this type of activity. Bathing in and drinking the warm, carbonated spring water only served as a prelude to the more interesting social activities of gambling, promenading, horse racing, and dancing.

During the last half of the 19th century, western entrepreneurs developed natural hot and cold springs into resorts — from the Mississippi River to the West Coast. Many of these spas offered individual tub baths, vapor baths, douche sprays, needle showers, and pool bathing to their guests. The various railroads that spanned the country promoted these resorts to encourage train travel. Hot Springs, Arkansas, became a major resort for people from the large metropolitan areas of St. Louis and Chicago.

The popularity of the spas continued into the 20th century. Some medical critics, however, posited that the thermal waters in such renowned resorts as Hot Springs, Virginia, and Saratoga Springs, New York, were no more beneficial to health than ordinary heated water. In response, various spa owners claimed to develop better hydrotherapy for their patients. At the Saratoga spa, treatments for heart and circulatory disorders, rheumatic conditions, nervous disorders, metabolic diseases, and skin diseases were developed. In 1910, the New York state government began purchasing the principal springs to protect them from exploitation.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt was governor of New York, he pushed for a European type of spa development at Saratoga. The architects for the new complex spent two years studying the technical aspects of bathing in Europe. Completed in 1933, the development had three bathhouses — Lincoln, Washington, and Roosevelt — a drinking hall, the Hall of Springs, and a building housing the Simon Baruch Research Institute. Four additional buildings composed the recreation area and housed arcades and a swimming pool decorated with blue faience terra-cotta tile. Saratoga Spa State Park's Neoclassical buildings were laid out in a grand manner, with formal perpendicular axes, solid brick construction, and stone and concrete Roman-revival detailing.

The spa was surrounded by a 1,200-acre (4.9 km) natural park that had 18 miles (29 km) of bridle paths, "with measured walks at scientifically calculated gradients through its groves and vales, with spouting springs adding unexpected touches to its vistas, with the tumbling waters of Geyser Brook flowing beneath bridges of the fine roads. Full advantage has been taken of the natural beauty of the park, but no formal landscaping". Promotional literature advertised the attractions directly outside the spa: shopping, horse races, and historic sites associated with revolutionary war history. New York Governor Herbert Lehman opened the new facilities to the public in July 1935.

Other leading spas in the U.S. during this period were French Lick, Indiana; Hot Springs and White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia; Hot Springs, Arkansas; and Warm Springs, Georgia. French Lick specialized in treating obesity and constipation through a combination of bathing and drinking the water and exercising. Hot Springs, Virginia, specialized in digestive ailments and heart diseases, and White Sulphur Springs, Virginia, treated these ailments and skin diseases. Both resorts offered baths where the water would wash continuously over the patients as they lay in a shallow pool. Warm Springs, Georgia, gained a reputation for reportedly treating infantile paralysis by a procedure of baths and exercise. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who earlier supported Saratoga, became a frequent visitor and promoter of this spa.

Recent trends

By the late 1930s more than 2,000 hot- or cold-springs health resorts were operating in the United States. This number had diminished greatly by the 1950s and continued to decline in the following two decades. In the recent past, spas in the U.S. emphasized dietary, exercise, or recreational programs more than traditional bathing activities.

Up until recently, the public bathing industry in the U.S. remained stagnant. Nevertheless, in Europe, therapeutic baths have always been very popular, and remain so today. The same is true in Japan, where the traditional hot springs baths, known as onsen, attract visitors.

Due to an increase in the popularity of the "wellness industry", such treatments are again becoming popular.

Regulation of the industry

The International Spa and Body Wrap Association (ISBWA) is an international association for spas and body wrap centers around the world. The main concern of the ISBWA is the regulation of the industry and the welfare of the consumers. Member organisations are to adhere to the ISBWA code of ethics.

The Uniform Swimming Pool, Spa and Hot Tub Code (USPSHTC) is a model code developed by the International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials (IAPMO) to govern the installation and inspection of plumbing systems associated with swimming pools, spas and hot tubs as a means of promoting the public's health, safety and welfare.

Gallery

-

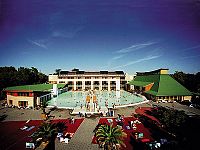

Flamingo Spa, a part of the Flamingo Entertainment Centre in Vantaa, Finland

Flamingo Spa, a part of the Flamingo Entertainment Centre in Vantaa, Finland

-

Spa center in Varshets, Bulgaria

Spa center in Varshets, Bulgaria

-

Spa in Hungary, 1939

Spa in Hungary, 1939

-

Mineral water swimming pools in Blagoevgrad district, Bulgaria

Mineral water swimming pools in Blagoevgrad district, Bulgaria

-

Balneo area in Alange

Balneo area in Alange

-

The casino garden in Spa, Belgium

The casino garden in Spa, Belgium

-

Medicinal water bath in Makó, Hungary

-

Bathing in Bogor, West Java

Bathing in Bogor, West Java

-

Japanese Onsen, in Hokkaido

-

Bathers, Louis Michel Eilshemius, c. 1920 (Brooklyn Museum)

Bathers, Louis Michel Eilshemius, c. 1920 (Brooklyn Museum)

-

Spa in Hungary, 1939

Spa in Hungary, 1939

-

Gellért baths in Budapest, Hungary

Gellért baths in Budapest, Hungary

-

Couple relaxing in Jacuzzi spa

Couple relaxing in Jacuzzi spa

-

Modern Spa Center in Andorra la Vella, Andorra

Modern Spa Center in Andorra la Vella, Andorra

See also

- Bathing#History

- Ganban'yoku

- Jacuzzi

- Jjimjilbang

- List of spa towns

- Onsen

- Peloids

- Sauna

- Spa, Belgium, a municipality of Belgium

- Uniform Swimming Pool, Spa and Hot Tub Code

- Water cure (therapy)

Notes

- Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, George Rosen, Yale University Dept. of the History of Science and Medicine, Project Muse, H. Schuman, 1954

- Van Tubergen, A.; Van Der Linden, S. (2002). "A brief history of spa therapy". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 61 (3): 273–275. doi:10.1136/ard.61.3.273. PMC 1754027. PMID 11830439. Archived from the original on 8 February 2006.

- Medical Hydrology, Sidney Licht, Sidney Herman Licht, Herman L. Kamenetz, E. Licht, 1963 Google Books

- For instance, 'Leisure and Recreation Management', George Torkildsen, Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0-415-30995-6 "Sanitas+Per+Aqua"&pg=PA37 Google Books

- "Hexmaster's Factoids: Spa". Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- Van Tubergen, A; Van Der Linden, S (2002). "A brief history of spa therapy". Ann Rheum Dis. 61 (3): 273–275. doi:10.1136/ard.61.3.273. PMC 1754027. PMID 11830439.

- ^ Paige, John C; Laura Woulliere Harrison (1987). Out of the Vapors: A Social and Architectural History of Bathhouse Row, Hot Springs National Park (PDF). U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- Squatriti, Paolo (2002). Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400-1000, Parti 400–1000. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780521522069.

... but baths were normally considered therapeutic until the days of Gregory the Great, who understood virtuous bathing to be bathing "on account of the needs of body" ...

- ^ Bradley, Ian (2012). Water: A Spiritual History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441167675.

- Thurlkill, Mary (2016). Sacred Scents in Early Christianity and Islam: Studies in Body and Religion. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 6–11. ISBN 978-0739174531.

... Clement of Alexandria (d. c. 215 CE) allowed that bathing contributed to good health and hygiene ... Christian skeptics could not easily dissuade the baths' practical popularity, however; popes continued to build baths situated within church basilicas and monasteries throughout the early medieval period ...

- Hembry, Phyllis (1990). The English Spa, 1560-1815: A Social History. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 9780838633915.

- Black, Winston (2019). The Middle Ages: Facts and Fictions. ABC-CLIO. p. 61. ISBN 9781440862328.

Public baths were common in the larger towns and cities of Europe by the twelfth century.

- Kleinschmidt, Harald (2005). Perception and Action in Medieval Europe. Boydell & Brewer. p. 61. ISBN 9781843831464.

- Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2010). "The Sparkling Nectar of Spas: The Medical and Commercial Relevance of Mineral Water". Ursula Klein and E. C. Spary (Eds.), Materials and Expertise in Early Modern Europe: 198–226. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226439709.003.0008. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015.

- Eddy (2008). "The Sparkling Nectar of Spas".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baths § Action of Baths on the Human System" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 518.

- Metcalfe, Richard (1877). Sanitus Sanitum et omnia Sanitus. Vol. 1. London: The Co-operative Printing Co. Retrieved 4 November 2009. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

- "London Gazette listings for 'Baths and Wash-houses Act'". London Gazette. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- "'Baths and Wash-houses Act'". Archived from the original on 2 May 2014..

- "Welche Kosten Krankenkassen bei einer Kur übernehmen" (in German).

- Gassan, Birth of American Tourism, 2008, pp. 1-9

- Chambers, Drinking the Waters, 2002

- Gassan, Birth of American Tourism, 2008

- Chambers, Drinking the Waters, Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002

- Gassan, Birth of American Tourism, pp. 125-157.

- Boyer-Lewis, Ladies and Gentlemen on Display, 2001.

- Chambers, Drinking the Waters, 2002.

- "The increasing focus on fitness and wellness has fuelled the reemergence of the spa industry..." Anne Williams, Spa bodywork: a guide for massage therapists. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006. p. 173. ISBN 0-7817-5578-6

- "International Spa and Body Wrap Association". Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013. International Spa and Body Wrap Association

Bibliography

- Nathaniel Altman, Healing springs: the ultimate guide to taking the waters : from hidden springs to the world's greatest spas. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-89281-836-0.

- Dian Dincin Buchman, The complete book of water healing. 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill Professional, 2001. ISBN 0-658-01378-5.

- Jane Crebbin-Bailey, John W. Harcup, John Harrington, The Spa Book: The Official Guide to Spa Therapy. Publisher: Cengage Learning EMEA, 2005. ISBN 1-86152-917-1.

- Esti Dvorjetski, Leisure, pleasure, and healing: spa culture and medicine in ancient eastern Mediterranean., Brill, 2007 (illustrated). ISBN 90-04-15681-X.

- Carola Koenig, Specialized Hydro-, Balneo-and Medicinal Bath Therapy. Publisher: iUniverse, 2005. ISBN 0-595-36508-6.

- Anne Williams, Spa bodywork: a guide for massage therapists. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006. ISBN 0-7817-5578-6.

- Richard Gassan, The Birth of American Tourism: New York, the Hudson Valley, and American Culture, 1790-1830. University of Massachusetts Press, 2008. ISBN 1-55849-665-3.

- Thomas Chambers, Drinking the Waters: Creating an American Leisure Class at Nineteenth-Century Mineral Springs. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002 (out of print).

- Charlene Boyer Lewis, Ladies and Gentlemen on Display: Planter Society at the Virginia Springs, 1790-1860. University of Virginia Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8139-2079-5.

External links

Media related to Spas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Spas at Wikimedia Commons- International Spa Association Official website