Clock skew (sometimes called timing skew) is a phenomenon in synchronous digital circuit systems (such as computer systems) in which the same sourced clock signal arrives at different components at different times due to gate or, in more advanced semiconductor technology, wire signal propagation delay. The instantaneous difference between the readings of any two clocks is called their skew.

The operation of most digital circuits is synchronized by a periodic signal known as a "clock" that dictates the sequence and pacing of the devices on the circuit. This clock is distributed from a single source to all the memory elements of the circuit, which for example could be registers or flip-flops. In a circuit using edge-triggered registers, when the clock edge or tick arrives at a register, the register transfers the register input to the register output, and these new output values flow through combinational logic to provide the values at register inputs for the next clock tick.

Ideally, the input to each memory element reaches its final value in time for the next clock tick so that the behavior of the whole circuit can be predicted exactly. The maximum speed at which a system can run must account for the variance that occurs between the various elements of a circuit due to differences in physical composition, temperature, and path length.

In a synchronous circuit, two registers, or flip-flops, are said to be "sequentially adjacent" if a logic path connects them. Given two sequentially adjacent registers Ri and Rj with clock arrival times at the source and destination register clock pins equal to TCi and TCj respectively, clock skew can be defined as: Tskew i, j = TCi − TCj.

In circuit design

Clock skew can be caused by many different things, such as wire-interconnect length, temperature variations, variation in intermediate devices, capacitive coupling, material imperfections, and differences in input capacitance on the clock inputs of devices using the clock. As the clock rate of a circuit increases, timing becomes more critical and less variation can be tolerated if the circuit is to function properly.

There are two types of clock skew: negative skew and positive skew. Positive skew occurs when the receiving register receives the clock tick later than the transmitting register. Negative skew is the opposite: the transmitting register gets the clock tick later than the receiving register. Zero clock skew refers to the arrival of the clock tick simultaneously at transmitting and receiving register.

Harmful skew

There are two types of violation that can be caused by clock skew. One problem is caused when the clock reaches the first register and the clock signal towards the second register travels slower than output of the first register into the second register - the output of the first register reaches the second register input faster and therefore is clocked replacing the initial data on the second register, or maybe destroying the integrity of the latched data. This is called a hold violation because the previous data is not held long enough at the destination flip-flop to be properly clocked through. Another problem is caused if the destination flip-flop receives the clock tick earlier than the source flip-flop - the data signal has that much less time to reach the destination flip-flop before the next clock tick. If it fails to do so, a setup violation occurs, so-called because the new data was not set up and stable before the next clock tick arrived. A hold violation is more serious than a setup violation because it cannot be fixed by increasing the clock period. Positive skew and negative skew cannot negatively impact setup and hold timing constraints respectively (see inequalities below).

Beneficial skew

Where a signal broadly clocks a circuit, the signals/state-transitions it initiates must be stabilized before it signals another set of state transitions -- and that limits the clock's upper frequency. Skew thus decreases the clock frequency at which the circuit will operate correctly. For each source register and destination register connected by a path, the following setup and hold inequalities must be obeyed:

where

- T is the clock period,

- reg is the source register's clock to Q delay,

- is the path with the longest delay from source to destination,

- J is an upper bound on jitter,

- S is the setup time of the destination register

- represents the clock skew from the source to the destination registers,

- is the path with the shortest delay from source to destination,

- H is the hold time of the destination register,

- is the clock skew to the destination register, and

- is the clock skew to the source register.

Positive clock skews are good for fixing setup violations, but can cause hold violations. Negative clock skew can guard against a hold violation, but can cause a setup violation.

In the above inequalities, a single parameter, J, is used to account for jitter. This parameter must be an upper bound for the difference in jitter over all source register/destination register pairs. However, if the structure of the clock distribution network is known, different source register/destination register pairs may have different jitter parameters, and a different jitter value may be used for the hold constraint in contrast to the value for the setup constraint. For example, if the source register and destination register receive their clock signals from a common nearby clock buffer, the jitter bound for that hold constraint can be very small, since any variation in that clock signal will affect the two registers equally. For the same example, the jitter bound for the setup constraint must be larger than for the hold constraint, because jitter can vary from clock tick to clock tick. If the source register receives its clock signal from a leaf buffer of the clock distribution network that is far removed from the leaf buffer feeding the destination register, then the jitter bound will have to be larger to account for the different clock paths to the two registers, which may have different noise sources coupling into them.

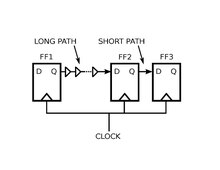

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a situation where intentional clock skew can benefit a synchronous circuit. In the zero-skew circuit of Figure 1, a long path goes from flip-flop FF1 to flip-flop FF2, and a short path, such as a shift-register path, from FF2 to FF3. The FF2 -> FF3 path is dangerously close to having a hold violation: If even a small amount of extra clock delay occurs at FF3, this could destroy the data at the D input of FF3 before the clock arrives to clock it through to FF3's Q output. This could happen even if FF2 and FF3 were physically close to each other, if their clock inputs happened to come from different leaf buffers of a clock distribution network.

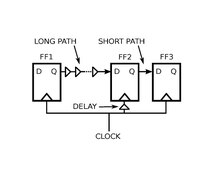

Figure 2 shows how the problem can be fixed with intentional clock skew. A small amount of extra delay is interposed before FF2's clock input, which then safely positions the FF2 -> FF3 path away from its hold violation. As an added benefit, this same extra clock delay relaxes the setup constraint for the FF1 -> FF2 path. The FF1 -> FF2 path can operate correctly at a clock period that is less than what is required for the zero clock skew case, by an amount equal to the delay of the added clock delay buffer.

A common misconception about intentional clock skew is that it is necessarily more dangerous than zero clock skew, or that it requires more precise control of delays in the clock distribution network. However it is the zero skew circuit of Figure 1 that is closer to malfunctioning - a small amount of positive clock skew for the FF2 -> FF3 pair will cause a hold violation, whereas the intentional skew circuit of Figure 2 is more tolerant of unintended delay variations in clock distribution.

Optimal skew

If the clock arrival times at individual registers are viewed as variables to be adjusted in order to minimize the clock period while satisfying the setup and hold inequalities for all of the paths through the circuit, then the result is a Linear Programming problem. In this linear program, zero clock skew is merely a feasible point - the solution to the linear program generally gives a clock period that is less than what is achieved by zero skew. In addition, safety margins greater than or equal to the zero skew case can be guaranteed by setting setup and hold times and jitter bound appropriately in the linear program.

Due to the simple form of this linear program, an easily programmed algorithm is available for arriving at a solution. Most CAD systems for VLSI and FPGA design contain facilities for optimizing clock skews.

Confusion between clock skew and clock jitter

In addition to clock skew due to static differences in the clock latency from the clock source to each clocked register, no clock signal is perfectly periodic, so that the clock period or clock cycle time varies even at a single component, and this variation is known as clock jitter. At a particular point in a clock distribution network, jitter is the only contributor to the clock timing uncertainty.

As an approximation, it is often useful to discuss the total clock timing uncertainty between two registers as the sum of spatial clock skew (the spatial differences in clock latency from the clock source), and clock jitter (meaning the non-periodicity of the clock at a particular point in the network). Unfortunately, spatial clock skew varies in time from one cycle to the next due to local time-dependent variations in the power supply, local temperature, and noise coupling to other signals.

Thus, in the usual case of sending and receiving registers at different locations, there is no clear way to separate the total clock timing uncertainty into spatial skew and jitter. Thus some authors use the term clock skew to describe the sum of spatial clock skew and clock jitter. This of course means that the clock skew between two points varies from cycle to cycle, which is a complexity that is rarely mentioned. Many other authors use the term clock skew only for the spatial variation of clock times, and use the term clock jitter to represent the rest of the total clock timing uncertainty. This of course means that the clock jitter must be different at each component, which again is rarely discussed.

Fortunately, in many cases, spatial clock skew remains fairly constant from cycle to cycle, so that the rest of the total clock timing uncertainty can be well approximated by a single common clock jitter value.

On a network

On a network such as the internet, clock skew describes the difference in frequency (first derivative of offset with time) of different clocks within the network. Network operations that require timestamps which are comparable across hosts can be affected by clock skew. A number of protocols (e.g. Network Time Protocol) have been designed to reduce clock skew, and produce more stable functions. Some applications (such as game servers) may also use their own synchronization mechanism to avoid reliability problems due to clock skew.

Interfaces

Clock skew is the reason why at fast speeds or long distances, serial interfaces (e.g. Serial Attached SCSI or USB) are preferred over parallel interfaces (e.g. parallel SCSI).

See also

References

- Friedman, Eby G. (1995). Clock Distribution Networks in VLSI Circuits and Systems. IEEE Press. ISBN 978-0-7803-1058-2.

- Friedman, Eby G. (May 2001). "Clock Distribution Networks in Synchronous Digital Integrated Circuits" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 89 (5): 665–692. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.7.7824. doi:10.1109/5.929649. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-01. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- Tam, S.; Limaye, D.L.; Desai, U.N. (April 2004). "Clock Generation and Distribution for the 130-nm Itanium 2 Processor with 6-MB On-Die L3 Cache". IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 39 (4). doi:10.1109/JSSC.2004.825121. S2CID 31388328.

- Friedman, E. G. Clock distribution design in VLSI circuits-an overview, 1993 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (pp. 1475-1478). IEEE, 1993.

- ^ Maheshwari, N., and Sapatnekar, S.S., Timing Analysis and Optimization of Sequential Circuits, Kluwer, 1999.

- Fishburn, J.P. (July 1990). "Clock skew optimization" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. 39 (7): 945–951. doi:10.1109/12.55696.

- Mills, D. (1992). "Network Time Protocol (Version 3) Specification, Implementation and Analysis". tools.ietf.org. doi:10.17487/RFC1305. Retrieved 2017-10-30.

is the path with the longest delay from source to destination,

is the path with the longest delay from source to destination, represents the clock skew from the source to the destination registers,

represents the clock skew from the source to the destination registers, is the path with the shortest delay from source to destination,

is the path with the shortest delay from source to destination, is the clock skew to the destination register, and

is the clock skew to the destination register, and is the clock skew to the source register.

is the clock skew to the source register.