Closed-circuit television (CCTV), also known as video surveillance, is the use of closed-circuit television cameras to transmit a signal to a specific place on a limited set of monitors. It differs from broadcast television in that the signal is not openly transmitted, though it may employ point-to-point, point-to-multipoint (P2MP), or mesh wired or wireless links. Even though almost all video cameras fit this definition, the term is most often applied to those used for surveillance in areas that require additional security or ongoing monitoring (videotelephony is seldom called "CCTV").

The deployment of this technology has facilitated significant growth in state surveillance, a substantial rise in the methods of advanced social monitoring and control, and a host of crime prevention measures throughout the world. Though surveillance of the public using CCTV is common in many areas around the world, video surveillance has generated significant debate about balancing its use with individuals' right to privacy even when in public.

In industrial plants, CCTV equipment may be used to observe parts of a process from a central control room, especially if the environments observed are dangerous or inaccessible to humans. CCTV systems may operate continuously or only as required to monitor a particular event. A more advanced form of CCTV, using digital video recorders (DVRs), provides recording for possibly many years, with a variety of quality and performance options and extra features (such as motion detection and email alerts). More recently, decentralized IP cameras, perhaps equipped with megapixel sensors, support recording directly to network-attached storage devices or internal flash for stand-alone operation.

History

An early mechanical CCTV system was developed in June 1927 by Russian physicist Léon Theremin. Originally requested by CTO (the Soviet Council of Labor and Defense), the system consisted of a manually-operated scanning-transmitting camera and wireless shortwave transmitter and receiver, with a resolution of a hundred lines. Having been commandeered by Kliment Voroshilov, Theremin's CCTV system was demonstrated to Joseph Stalin, Semyon Budyonny, and Sergo Ordzhonikidze, and subsequently installed in the courtyard of the Moscow Kremlin to monitor approaching visitors.

Another early CCTV system was installed by Siemens AG at Test Stand VII in Peenemünde, Nazi Germany, in 1942, for observing the launch of V-2 rockets.

In the United States, the first commercial closed-circuit television system became available in 1949 from Remington Rand and designed by CBS Laboratories, called "Vericon". Vericon was advertised as not requiring a government permit due to the system using cabled connections between camera and monitor rather than over-the-air transmission.

Technology

The earliest video surveillance systems involved constant monitoring because there was no way to record and store information. The development of reel-to-reel media enabled the recording of surveillance footage. These systems required magnetic tapes to be changed manually, with the operator having to manually thread the tape from the tape reel through the recorder onto a take-up reel. Due to these shortcomings, video surveillance was not widespread.

Later, videocassette recorder technology became available in the 1970s, making it easier to record and erase information, and the use of video surveillance became more common. During the 1990s, digital multiplexing was developed, allowing several cameras to record at once, as well as time lapse and motion-only recording. This saved time and money which then led to an increase in the use of CCTV. Recently, CCTV technology has been shifting towards Internet-based products and systems, and other technological developments.

Application

Early CCTV systems were installed in central London by the Metropolitan Police between 1960 and 1965. By 1963, CCTV was being used in Munich to monitor traffic. Closed-circuit television was used as a form of pay-per-view theatre television for sports such as professional boxing and professional wrestling, and from 1964 through 1970, the Indianapolis 500 automobile race. Boxing telecasts were broadcast live to a select number of venues, mostly theaters, with arenas, stadiums, schools, and convention centres also being less often used venues, where viewers paid for tickets to watch the fight live. The first fight with a closed-circuit telecast was Joe Louis vs. Joe Walcott in 1948.

Closed-circuit telecasts peaked in popularity with Muhammad Ali in the 1960s and 1970s, with "The Rumble in the Jungle" fight drawing 50 million CCTV viewers worldwide in 1974, and the "Thrilla in Manila" drawing 100 million CCTV viewers worldwide in 1975. In 1985, the WrestleMania I professional wrestling show was seen by over one million viewers with this scheme. As late as 1996, the Julio César Chávez vs. Oscar De La Hoya boxing fight had 750,000 viewers. Although closed-circuit television was gradually replaced by pay-per-view home cable television in the 1980s and 1990s, it is still in use today for most awards shows and other events that are transmitted live to most venues but do not air as such on network television, and later re-edited for broadcast.

In September 1968, Olean, New York, was the first city in the United States to install CCTV video cameras along its main business street in an effort to fight crime. Marie Van Brittan Brown received a patent for the design of a CCTV-based home security system in 1969. (U.S. patent 3,482,037). Another early appearance was in 1973 in Times Square in New York City. The NYPD installed it to deter crime in the area; however, crime rates did not appear to drop much due to the cameras. Nevertheless, during the 1980s, video surveillance began to spread across the country specifically targeting public areas. It was seen as a cheaper way to deter crime compared to increasing the size of the police departments. Some businesses as well, especially those that were prone to theft, began to use video surveillance. From the mid-1990s on, police departments across the country installed an increasing number of cameras in various public spaces including housing projects, schools, and public parks. CCTV later became common in banks and stores to discourage theft by recording evidence of criminal activity. In 1997, 3,100 CCTV systems were installed in public housing and residential areas in New York City.

Experiments in the UK during the 1970s and 1980s, including outdoor CCTV in Bournemouth in 1985, led to several larger trial programs later that decade. The first use by local government was in King's Lynn, Norfolk, in 1987.

Uses

Crime prevention

A 2008 report by UK Police Chiefs concluded that only 3% of crimes were solved by CCTV. In London, a Metropolitan Police report showed that in 2008 only one crime was solved per 1000 cameras. In some cases CCTV cameras have become a target of attacks themselves. A 2009 systematic review by researchers from Northeastern University and the University of Cambridge used meta-analytic techniques to pool the average effect of CCTV on crime across 41 different studies. The studies included in the meta-analysis used quasi-experimental evaluation designs that involved before-and-after measures of crime in experimental and control areas. However, researchers have argued that the British car park studies included in the meta-analysis cannot accurately control for the fact that CCTV was introduced simultaneously with a range of other security-related measures. Second, some have noted that, in many of the studies, there may be issues with selection bias since the introduction of CCTV was potentially endogenous to previous crime trends. In particular, the estimated effects may be biased if CCTV is introduced in response to crime trends.

In 2012, cities such as Manchester in the UK are using DVR-based technology to improve accessibility for crime prevention. In 2013, City of Philadelphia Auditor found that the $15 million system was operational only 32% of the time. There is anecdotal evidence that CCTV aids in detection and conviction of offenders; for example, UK police forces routinely seek CCTV recordings after crimes. Cameras have also been installed on public transport in the hope of deterring crime.

A 2017 review published in the Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention compiles seven studies that use such research designs. The studies found that CCTV reduced crime by 24–28% in public streets and urban subway stations. It also found that CCTV could decrease unruly behaviour in football stadiums and theft in supermarkets/mass merchant stores. However, there was no evidence of CCTV having desirable effects in parking facilities or suburban subway stations. Furthermore, the review indicates that CCTV is more effective in preventing property crimes than in violent crimes. However, a 2019, 40-year-long systematic review study reported that the most consistent effects of crime reduction of CCTV were in car parks.

A more open question is whether most CCTV is cost-effective. While low-quality domestic kits are cheap, the professional installation and maintenance of high definition CCTV is expensive. Gill and Spriggs did a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) of CCTV in crime prevention that showed little monetary saving with the installation of CCTV as most of the crimes prevented resulted in little monetary loss. Critics however noted that benefits of non-monetary value cannot be captured in a traditional cost effectiveness analysis and were omitted from their study.

In October 2009, an "Internet Eyes" website was announced which would pay members of the public to view CCTV camera images from their homes and report any crimes they witnessed. The site aimed to add "more eyes" to cameras which might be insufficiently monitored. Civil liberties campaigners criticized the idea as "a distasteful and a worrying development". Russia has also implemented a video surveillance system called 'Safe City', which has the capability to recognize facial features and moving objects, sending the data automatically to government authorities. However, the widespread tracking of individuals through video surveillance has raised significant privacy issues.

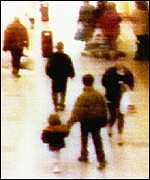

Forensics

Material collected by surveillance cameras has been used as a tool in post-event forensics to identify tactics and perpetrators of terrorist attacks. Furthermore, there are various projects—such as INDECT—that aim to detect suspicious behaviours of individuals and crowds. It has been argued that terrorists will not be deterred by cameras, that terror attacks are not really the subject of the current use of video surveillance and that terrorists might even see it as an extra channel for propaganda and publication of their acts. In Germany, calls for extended video surveillance by the country's main political parties, SPD, CDU, and CSU have been dismissed as "little more than a placebo for a subjective feeling of security" by a member of the Left party.

In Singapore, since 2012, thousands of CCTV cameras have helped deter loan sharks, nab litterbugs, and stop illegal parking, according to government figures. In 2013, Oaxaca, Mexico, hired deaf police officers to lip read conversations to uncover criminal conspiracies.

Body-worn cameras

Main article: Body worn videoIn recent years, the use of body-worn video cameras has been introduced for a number of uses. For example, as a new form of surveillance in law enforcement, there are surveillance cameras that are worn by the police officer and are usually located on a police officer's chest or head. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), in the United States, in 2016, about 47% of the 15,328 general-purpose law enforcement agencies had acquired body-worn cameras.

Traffic flow monitoring

Main article: Traffic cameraMany cities and motorway networks have extensive traffic-monitoring systems. Many of these cameras however, are owned by private companies and transmit data to drivers' GPS systems.

Highways England has a publicly owned CCTV network of over 3000 pan–tilt–zoom cameras covering the British motorway and trunk road network. These cameras are primarily used to monitor traffic conditions and are not used as speed cameras. With the addition of fixed cameras for the active traffic management system, the number of cameras on the Highways England's CCTV network is likely to increase significantly over the next few years. The London congestion charge is enforced by cameras positioned at the boundaries of and inside the congestion charge zone, which automatically read the number plates of vehicles that enter the zone. If the driver does not pay the charge then a fine will be imposed. Similar systems are being developed as a means of locating cars reported stolen. Other surveillance cameras serve as traffic enforcement cameras.

In Mecca, Saudi Arabia, CCTV cameras are used for monitoring (and thus managing) the flow of crowds. In the Philippines, barangay San Antonio used CCTV cameras and artificial intelligence software to detect the formation of crowds during an outbreak of a disease. Security personnel were sent whenever a crowd formed at a particular location in the city.

Use in homes and buildings

In schools

Further information: Video surveillance in schoolsIn the United States, Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, CCTV is widely used in schools to prevent bullying, vandalism, monitoring visitors, and maintaining a record of evidence of a crime. There are some restrictions: cameras are not typically installed in areas where there is a "reasonable expectation of privacy", such as bathrooms, gym locker areas, and private offices. Cameras are generally acceptable in parking lots, cafeterias, and supply rooms. Though some teachers object to the installation of cameras. A study of high school students in Israeli schools shows that students' views on CCTV used in school are based on how they think of their teachers, school, and authorities. It also stated that most students do not want CCTV installed inside a classroom.

In private and public places

Many homeowners choose to install CCTV systems either inside or outside their own homes, sometimes both. Modern CCTV systems can be monitored through mobile phone apps with internet coverage. Some systems also provide motion detection, so when movement is detected, an alert can be sent to a phone.

On a driver-only operated train, CCTV cameras may allow the driver to confirm that people are clear of doors before closing them and starting the train. A trial by RET in 2011 with facial recognition cameras mounted on trams made sure that people who were banned from them did not sneak on anyway. CCTV has also been frequently operated in many department stores and shopping malls to mitigate concerns of potential theft. In some countries, malls must obtain approval from the Ministry of Interior (MOI) or Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) before installing CCTVs. Some organizations also use CCTV to monitor the actions of workers in a workplace.

Many sporting events in the United States use CCTV inside the venue, either to display on the stadium or arena's scoreboard or in the concourse or restroom areas to allow people to view action outside the seating bowl. The cameras send the feed to a central control centre where a producer selects feeds to send to the television monitors that people can view. In a trial with CCTV cameras, football club fans no longer needed to identify themselves manually, but could pass freely after being authorized by the facial recognition system.

Criminal use

Criminals may use surveillance cameras to monitor the public. For example, a hidden camera at an ATM can capture people's PINs as they are entered without their knowledge. The devices are small enough not to be noticed, and are placed where they can monitor the keypad of the machine as people enter their PINs. Images may be transmitted wirelessly to the criminal. Even lawful surveillance cameras sometimes have their data received by people who have no legal right to receive it.

Prevalence

In Asia

About 65% of CCTV cameras in the world are installed in Asia. In Asia, different human activities attracted the use of surveillance camera systems and services, including but not limited to business and related industries, transportation, sports, and care for the environment.

In 2018, China was reported to have over 170 million CCTV cameras. In 2023, China was estimated to have a huge surveillance network of around 540–626 million surveillance cameras, though numbers differ significantly between sources. Beijing, China's capital city, has the most cameras for a city overall, with a total of 1.15 million installed. The cameras are used to record details such as gender, age, and ethnicity. Cameras have been used in a southern Chinese city to issue tickets to people for infractions. In India, the cities of Hyderabad and Delhi, the capital, have around 900,000 and 450,000 cameras, respectively. The city of Chennai has the highest density per area of CCTV cameras worldwide, with 657 cameras per square kilometer in 2020 (from 280,000 CCTVs). China and India have some of the highest-density and the most amount of CCTVs in cities.

South Korea's military has removed over 1,300 surveillance Chinese cameras from its bases for security reasons. In Hong Kong, the police have stated that they are planning to install up to 7,000 surveillance cameras across Hong Kong in roughly three years time, up from the estimated 600 installed cameras in 2024; this amounts to roughly 2,000 planned cameras every year starting from 2025. Earlier, in June 2024, the cameras have also been vaguely planned to be integrated with facial recognition artificial intelligence. The plan has been criticized for the potential for the country to become similar to the "intense surveillance of mainland China". In Japan, an estimation by Nikkei Business estimated that the total number of security cameras in Japan is approximately 5 million in 2018. In Singapore, it was estimated that the total number of CCTVs was around 90,000 in 2021.

In the Americas

In 2009, there were an estimated 15,000 CCTV systems in Chicago, many linked to an integrated camera network. New York City's Domain Awareness System has 6,000 video surveillance cameras linked together, there are over 4,000 cameras on the subway system (although nearly half of them do not work), and two-thirds of large apartment and commercial buildings use video surveillance cameras. In Washington, D.C., there are more than 30,000 surveillance cameras in schools, and the Metro has nearly 6,000 cameras in use across the system.

There were an estimated 30 million surveillance cameras in the United States in 2011. Video surveillance has been common in the United States since the 1990s; for example, one manufacturer reported net earnings of $120 million in 1995. With lower cost and easier installation, sales of home security cameras increased in the early 21st century. Following the September 11 attacks, the use of video surveillance in public places became more common to deter future terrorist attacks. Under the Homeland Security Grant Program, government grants are available for cities to install surveillance camera networks. In 2018, there are approximately 70 million surveillance cameras in the United States.

In Canada, Project SCRAM is a policing effort by the Canadian policing service Halton Regional Police Service to register and help consumers understand privacy and safety issues related to the installations of home security systems. The project service has not been extended to commercial businesses.

In Latin America, the CCTV market is growing rapidly with the increase of property crime. In Brazil, CCTV usage is only permitted in public areas, though individuals must be informed about the presence of the camera according to the Brazilian LGPD (which broadly aligns with the EU's GDPR), the Brazilian Civil Code, and the Brazilian Association of Technical Standards. However, starting in 2023, in Brazil, the Smart Sampa project, a project that plans to deploy 20,000 facial recognition cameras by 2024, has been criticized for its potential to be "biased against Black individuals" and overall risks of data privacy.

In Russia

In 2017, in Russia, the Moscow network included 160,000 CCTV cameras and 95 percent of residential buildings; over 3,500 Russian cameras were connected to the General Centre for Data Storage and Processing. Video recordings are used to solve 70 percent of offenses and crimes. In 2024, there are over 1 million video surveillance cameras in Russia. About 230,000 are in use in Moscow alone. According to data from the Russian Minister for Digital Development, Maksut Shadayev, one in three of all CCTVs in Russia were connected to a facial recognition system. A leaked document revealed that the president of Russia, Vladimir Putin, called on the Russian security services to fund "a massive AI-based surveillance apparatus". The spending of over US$115 million was planned for the system in 2024–2026.

In Europe

In the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the vast majority of CCTV cameras are operated not by government bodies, but by private individuals or companies, especially to monitor the interiors of shops and businesses. According to the Freedom of Information Act 2000 requests, the total number of local government-operated CCTV cameras was around 52,000 over the entirety of the UK.

An article published in CCTV Image magazine estimated the number of private and local government-operated cameras in the United Kingdom was 1.85 million in 2011. The estimate was based on extrapolating from a comprehensive survey of public and private cameras within the Cheshire Constabulary jurisdiction. This works out as an average of one camera for every 32 people in the UK, although the density of cameras varies greatly from place to place. The Cheshire report also claims that the average person on a typical day would be seen by 70 CCTV cameras.

The Cheshire figure is regarded as more dependable than a previous study by Michael McCahill and Clive Norris of UrbanEye published in 2002. Based on a small sample in Putney High Street, McCahill and Norris extrapolated the number of surveillance cameras in Greater London to be around 500,000 and the total number of cameras in the UK to be around 4.2 million. According to their estimate, the UK has one camera for every 14 people. Although it has been acknowledged for several years that the methodology behind this figure is flawed, it has been widely quoted. Furthermore, the figure of 500,000 for Greater London is often confused with the figure for the police and local government-operated cameras in the City of London, which was about 650 in 2011.

The CCTV User Group estimated that there were around 1.5 million private and local government CCTV cameras in city centres, stations, airports, and major retail areas in the UK. Research conducted by the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research and based on a survey of all Scottish local authorities identified that there are over 2,200 public space CCTV cameras in Scotland. The UK has often been cited as a country that has one of the most CCTV cameras in Europe.

In Africa

In South Africa, due to the high crime rate, CCTV surveillance is widely prevalent. The first IP camera was released in 1996 by Axis Communications, but IP cameras did not arrive in South Africa until 2008. To regulate the number of suppliers in 2001, the Private Security Industry Regulation Act was passed requiring all security companies to be registered with the Private Security Industry Regulatory Authority (PSIRA). In Egypt, the capital city of Cairo has approximately 47,000 cameras, while the New Administrative Capital has more than 6,000 surveillance cameras in 2023. In South Sudan, the Ministry of Interior has reinstated the operation of CCTV surveillance cameras in Juba after the cameras have been inactive for over four years; South Sudan also launched a drone security system in 2024 in Juba.

Privacy

Proponents of CCTV cameras argue that cameras are effective at deterring and solving crime, and that appropriate regulation and legal restrictions on surveillance of public spaces can provide sufficient protections so that an individual's right to privacy can reasonably be weighed against the benefits of surveillance. However, anti-surveillance activists have held that there is a right to privacy in public areas, that the development of CCTV in public areas, linked to databases of people's pictures and identity, presents a breach of civil liberties and the loss of anonymity in public places.

Furthermore, some scholars have argued that situations wherein a person's rights can be justifiably compromised are so rare as to not sufficiently warrant the frequent compromising of public privacy rights that occurs in regions with widespread CCTV surveillance. For example, in her book Setting the Watch: Privacy and the Ethics of CCTV Surveillance, Beatrice von Silva-Tarouca Larsen argues that CCTV surveillance is ethically permissible only in "certain restrictively defined situations", such as when a specific location has a "comprehensively documented and significant criminal threat".

Law by countries

In the United States, the Constitution does not explicitly include the right to privacy although the Supreme Court has said several of the amendments to the Constitution implicitly grant this right. Access to video surveillance recordings may require a judge's writ, which is readily available. However, there is little legislation and regulation specific to video surveillance. In Canada, the use of video surveillance has grown very rapidly. In Ontario, both the municipal and provincial versions of the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act outline guidelines that control how images and information can be gathered by this method and or released.

All countries in the European Union are signatories to the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects individual rights, including the right to privacy. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) required that the footage should only be retained for as long as necessary for the purpose for which it was collected. In Sweden, the use of CCTV in public spaces is regulated both nationally and via GDPR. In an opinion poll commissioned by Lund University in August 2017, the general public of Sweden was asked to choose one measure that would ensure their need for privacy when subject to CCTV operation in public spaces: 43% favored regulation in the form of clear routines for managing, storing, and distributing image material generated from surveillance cameras, 39% favored regulation in the form of clear signage informing that camera surveillance in public spaces is present, 10% favored regulation in the form of having restrictive policies for issuing permits for surveillance cameras in public spaces, 6% were unsure, and 2% favored regulation in the form of having permits restricting the use of surveillance cameras during certain times.

In the United Kingdom, the Data Protection Act 1998 imposes legal restrictions on the uses of CCTV recordings and mandates the registration of CCTV systems with the Data Protection Agency. In 2004, the successor to the Data Protection Agency, the Information Commissioner's Office, clarified that this required registration of all CCTV systems with the Commissioner and prompt deletion of archived recordings. However, subsequent case law (Durant vs. FSA) limited the scope of the protection provided by this law, and not all CCTV systems are currently regulated.

A 2007 report by the UK Information Commissioner's Office highlighted the need for the public to be made more aware of the growing use of surveillance and the potential impact on civil liberties. In the same year, a campaign group claimed that the majority of CCTV cameras in the UK are operated illegally or are in breach of privacy guidelines. In response, the Information Commissioner's Office rebutted the claim and added that any reported abuses of the Data Protection Act are swiftly investigated. Even if there are some concerns arising from the use of CCTV such as involving privacy, more commercial establishments are still installing CCTV systems in the UK. In 2012, the UK government enacted the Protection of Freedoms Act which includes several provisions related to controlling the storage and use of information about individuals. Under this Act, the Home Office published a code of practice in 2013 for the use of surveillance cameras by government and local authorities. The code wrote that "surveillance by consent should be regarded as analogous to policing by consent."

In the Philippines, the main laws governing CCTV usage are Data Privacy Act of 2012 and the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012. The Data Privacy Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10173) is the primary law that governs data privacy in the Philippines. The Act mandates that the privacy of individuals must be respected and protected. The law applies to CCTV cameras as they collect and process personal data. The Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10175) includes provisions that apply to CCTV usage. Under the Act, the unauthorized access to, interception of, or interference with data is a criminal offense. This means that unauthorized access to CCTV footage could potentially be considered a cybercrime.

Technological developments

Computer-controlled identification

Computer-controlled cameras can identify, track, and categorize objects in their field of view. Video content analysis, also referred to as video analytics, is the capability of automatically analyzing video to detect and determine temporal events not based on a single image but rather on object classification. Advanced VCA applications can measure object speed. Some video analytics applications can be used to apply rules to designated areas. These rules can relate to access control. For example, they can describe which objects can enter into a specific area. There are different approaches to implementing VCA technology. Data may be processed on the camera itself (edge processing) or by a centralized server. Artificial intelligence-powered CCTV cameras have also been further tested to detect congestion, be used as a facial recognition system, and predict signs of criminal activities.

Compression

There is a cost in the retention of the images produced by CCTV systems. The amount and quality of data stored on storage media is subject to compression ratios, images stored per second, and image size, and is affected by the retention period of the videos or images. DVRs store images in a variety of proprietary file formats. CCTV security cameras can either store the images on a local hard disk drive, an SD card, or in the cloud. Recordings may be retained for a preset amount of time and then automatically archived, overwritten, or deleted, the period being determined by the organisation that generated them.

IP cameras

Main article: IP camera

A growing branch in CCTV is internet protocol cameras (IP cameras). It is estimated that 2014 was the first year that IP cameras outsold analog cameras. IP cameras use the Internet Protocol (IP) used by most local area networks (LANs) to transmit video across data networks in digital form. IP can optionally be transmitted across the public internet, allowing users to view their cameras remotely on a computer or phone via an internet connection. IP cameras are considered part of the Internet of things (IoT) and have many of the same benefits and security risks as other IP-enabled devices. Smart doorbells are one example of a type of CCTV that uses IP to allow it to send alerts.

Main types of IP cameras include fixed cameras, pan–tilt–zoom (PTZ) cameras, and multi-sensor cameras. Fixed cameras' resolution typically does not exceed 20 megapixels. The main feature of a PTZ is its remote directional and optical zoom capability. With multi-sensor cameras, wider areas can be monitored. Industrial video surveillance systems use network video recorders to support IP cameras. These devices are responsible for the recording, storage, video stream processing, and alarm management. Since 2008, IP video surveillance manufacturers can use a standardized network interface (ONVIF) to support compatibility between systems. For professional or public infrastructure security applications, IP video is restricted to within a private network or VPN.

Networking CCTV cameras

The city of Chicago operates a networked video surveillance system which combines CCTV video feeds of government agencies with those of the private sector, installed in city buses, businesses, public schools, subway stations, housing projects, etc. Even homeowners are able to contribute footage. It is estimated to incorporate the video feeds of a total of 15,000 cameras. The system is used by Chicago's Office of Emergency Management in case of an emergency call: it detects the caller's location and instantly displays the real-time video feed of the nearest security camera to the operator, not requiring any user intervention. While the system is far too vast to allow complete real-time monitoring, it stores the video data for use as evidence in criminal cases.

Wireless security cameras

Main article: Wireless security camera

Many consumers are turning to wireless security cameras for home surveillance. Wireless cameras do not require a video cable for video/audio transmission, simply a cable for power. Wireless cameras are also easy and inexpensive to install. Previous generations of wireless security cameras relied on analogue technology; modern wireless cameras use digital technology with usually more secure and interference-free signals. Wireless mesh networks have been used for connection with the other radios in the same group. There are also cameras using solar power. Wireless IP cameras can become a client on the WLAN, and they can be configured with encryption and authentication protocols with a connection to an access point.

Talking CCTV

Main article: Talking CCTVIn Wiltshire, United Kingdom, in 2003, a pilot scheme for what is now known as "Talking CCTV" was put into action, allowing operators of CCTV cameras to communicate through the camera via a speaker when it is needed. In 2005, Ray Mallon, the mayor and former senior police officer of Middlesbrough, implemented "Talking CCTV" in his area. Other towns have had such cameras installed. In 2007, several of the devices were installed in Bridlington town centre, East Riding of Yorkshire.

Countermeasures

In December 2016, a form of anti-CCTV and facial recognition sunglasses called "reflectacles" were invented by a craftsman based in Chicago named Scott Urban. They reflect infrared and, optionally, visible light which makes the user's face a white blur to cameras. The project passed its funding goal of $28,000, and "reflectacles" became commercially available in June 2017.

See also

- Artificial intelligence for video surveillance

- Bugging

- "CATV" as cable television—not to be confused with CCTV

- Closed-circuit television camera

- Day and night camera

- Effio, uncompressed analog streaming video format

- Eye in the sky (camera)

- Fake security camera

- INDECT

- IP camera

- Security operations center

- Security smoke

- Smart camera

- Sousveillance (inverse surveillance)

- Surveillance

- The Convention on Modern Liberty

- TV Network Protocol

- Under vehicle inspection

- Video analytics

- Video evidence

- Videotelephony

- Washington County Closed-Circuit Educational Television Project

- Surveillance drone

References

- Kumar, Vikas; Svensson, Jakob, eds. (2015). Promoting Social Change and Democracy Through Information Technology. IGI Global. p. 75. ISBN 9781466685031.

- Dempsey, John S. (2008). Introduction to private security. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 78. ISBN 9780534558734.

- Verman, Romesh. Distance Education In Technological Age, Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., 2005, pp.166, ISBN 81-261-2210-2, ISBN 978-81-261-2210-3.

- "Distance education in Asia and the Pacific: Proceedings Of The Regional Seminar On Distance Education, 26 November – 3 December 1986", Asian Development Bank, Bangkok, Thailand, Volume 2, 1987

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 114.

- "What's wrong with public video surveillance?". ACLU. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Surveillance Cameras and the Right to Privacy". CBS News. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Best PoE Security Camera System". CBS News. 9 November 2019. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Glinsky, Albert. (2000). Theremin: ether music and espionage. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0252025822. OCLC 43286443.

- Dornberger, Walter: V-2, Ballantine Books 1954, ASIN: B000P6L1ES, page 14.

- "Agreement Seen Spur to Color TV" , August 16, 1950,, New York Times

- "Television Rides Wires" , February 1949, Popular Science small article, bottom of page 179

- ^ Kruegle, Herman (15 March 2011). CCTV Surveillance. Elsevier. ISBN 9780080468181.

- ^ Roberts, Lucy. "History of Video Surveillance and CCTV Archived 21 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine" We C U Surveillance Retrieved 2011-10-20

- "Internet based CCTV on cloud services" (in Finnish). fennoturvapalvelut. 27 March 2015.

- "Police's 1960s CCTV experiments, part 1". Professional Security Magazine Online. 2023.

- "Police's 1960s CCTV experiments, part 2". Professional Security Magazine Online. 2023.

- ^ Ezra, Michael (2013). The Economic Civil Rights Movement: African Americans and the Struggle for Economic Power. Routledge. p. 105. ISBN 9781136274756.

- ^ "History of Prizefighting's Biggest Money Fights". Bloody Elbow. SB Nation. 24 August 2017.

- Television. Frederick A. Kugel Company. 1965. p. 78.

Teleprompter's main-spring, Irving B. Kahn (he's chairman of the board and president), had a taste of closed circuit operations as early as 1948. That summer, Kahn, then a vice president of 20th Century-Fox, negotiated what was probably the first inter-city closed circuit telecast in history, a pickup of the Joe Louis-Joe Walcott fight.

- "Zaire's fight promotion opens new gold mines". The Morning Herald. 18 November 1974.

- "Karriem Allah". Black Belt. Active Interest Media, Inc.: 35 1976.

- "Wrestlemania In Photographs: 1-10". Sportskeeda. 1 April 2017.

- Chavez-De La Hoya Fight Is A Bout About Contrasts, Chicago Tribune article, 1996-06-07, Retrieved on 2015-02-23

- ^

- Who's Watching? Video Camera Surveillance in New York City and the Need for Public Oversight (PDF). 2006. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- Staff (August 2007). "CCTV". Borough Council of King's Lynn & West Norfolk. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "Are CCTV cameras a waste of money in the fight against crime?" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Forward Edge, 7 May 2008

- Hughe, Mark (25 August 2009). "CCTV in the spotlight: one crime solved for every 1,000 cameras". Independent News and Media Limited.

- "http://news.bbc.co.uk/" BBC

- ^ "Public Area CCTV and Crime Prevention: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journalist's Resource.org. 11 February 2014.

- Zehnder (2009). "The economics of subjective security and camera surveillance" (PDF). WWZ Research Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- Priks, Mikael (1 November 2015). "The Effects of Surveillance Cameras on Crime: Evidence from the Stockholm Subway". The Economic Journal. 125 (588): F289 – F305. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12327. ISSN 1468-0297. S2CID 96452277.

- Stutzer (2013). "Is camera surveillance an effective measure of counterterrorism?". Defence and Peace Economics. 24: 1–14. doi:10.1080/10242694.2011.650481.

- "Digital CCTV scheme switches on". BBC News. 28 June 2002. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- "Orphaned Video System in Philadelphia?". May 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Police are failing to recover crucial CCTV footage, new figures suggest", The Daily Telegraph

- "CCTV to drive down cab attacks". 11 September 2003. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- "Taxi CCTV cameras are installed". 25 February 2005. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- Gustav Alexandrie (2017). "Surveillance cameras and crime: a review of randomized and natural experiments". Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention. 18 (2): 210–222. doi:10.1080/14043858.2017.1387410. S2CID 149144413.

- Piza, Eric L.; Welsh, Brandon C.; Farrington, David P.; Thomas, Amanda L. (2019). "CCTV surveillance for crime prevention: A 40-year systematic review with meta-analysis". Criminology & Public Policy. 18 (1): 135–159. doi:10.1111/1745-9133.12419. ISSN 1538-6473.

- "National community Crime Prevention Programme" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Assessing the impact of CCTV" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Public to Monitor CCTV From Home, BBC

- Artificial intelligence in local government services: Public perceptions from Australia and Hong Kong, Government Information Quarterly, Volume 40, Issue 3, June 2023, 101833

- Mould, Nick; Regens, James L.; Jensen, Carl J.; Edger, David N. (30 August 2014). "Video surveillance and counterterrorism: the application of suspicious activity recognition in visual surveillance systems to counterterrorism". Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism. 9 (2): 151–175. doi:10.1080/18335330.2014.940819. S2CID 62710484.

- "In the Petabyte Age of Surveillance, Software Polices". Popular Mechanics. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- "Mehr Videoüberwachung gegen Terroristen - WDR aktuell - Sendung - Video - Mediathek - WDR". WDR. 26 October 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- "Calls increase for sweeping surveillance after Berlin attack". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- "Network of CCTV cameras proving effective". straitstimes. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- Maria Alvarez, Jose (20 November 2013). "Mexico's Angels of Silence: Deaf police officers see crime where others don't". Globe & Mail. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013.

- Bayley, David H.; Stenning, Philip C. (2016). Governing the Police: Experience in Six Democracies. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1412862318.

- Hung, Vivian; Babin, Steven; Coberly, Jacqueline. "A Market Survey on Body Worn Camera Technologies" (PDF). The Department of Justice's National Institute of Justice. Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- S. Hyland, Shelley (November 2018). "Body-Worn Cameras in Law Enforcement Agencies, 2016, NCJ 251775" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Networx Security. "Closed Circuit Television." Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Kablenet, The Register. "TfL hands out contracts for congestion charge tags." 6 June 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Rowena Coetsee, Bay Area News Group. "New surveillance cameras doing their job, Antioch's top cop says." 11 August 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- Volokh, Eugene (26 March 2002). "Traffic Enforcement Cameras". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Saudi Arabia installs new security cameras in Makkah". Al Arabiya English. 26 May 2016.

- "AI-equipped CCTV cameras enable a barangay to monitor people out on the streets". TopGear Philippines. 27 March 2020.

- "Pasig barangay turns to smart CCTV to enforce social distancing". GMA News Online. Philippines. 27 March 2020. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022.

- "Use of CCTV surveillance in schools". ATL the education union. 22 October 2013. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Bruce McDougall and Katherine Danks (28 March 2012). "School security CCTV puts bullies on pause". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- "Legal aspects of the use of video cameras in schools =". Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Birnhack, Michael D.; Perry-Hazan, Lotem (2020). "School Surveillance in Context: High School Students' Perspectives on CCTV, Privacy, and Security". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3587450. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 234991261.

- Wollerton, Megan. "Turn an old phone into a security camera in 3 steps. Here's how to do it". cnet.com. CNET. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- FCC Train Dispatch training video. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2018 – via YouTube. (From 7:35, the video explains about DOO train dispatch and describes the use of CCTV at stations.)

- "Facial recognition cameras to be installed on Rotterdam trams". 11 September 2011.

- "Leading New Steps for MOI CCTV Approval for Malls". Axle Systems. 19 May 2024. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- "A Quick Guide to CCTV Systems for Retail Centres | ACCL". ACCL Network Data Cabling. 4 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- "Using CCTV to monitor the workplace". icaew. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "Doe mee aan de proef met gezichtsherkenning" [Participate in the facial recognition trial]. Heracles (in Dutch). 26 March 2019.

- "Benalla. Trois policiers suspendus pour avoir transmis des images de vidéosurveillance" [Benalla: Three police officers suspended for transmitting video surveillance images] (in French). 20 July 2018.

- khris78. "The CCTV Map". osmcamera. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Rise of Surveillance Camera Installed Base Slows". SDM Magazine. 5 May 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Walton, Greg (2001). China's Golden Shield: corporations and the development of surveillance technology in the People's Republic of China. Rights & Democracy.

- "Australian state government to expand CCTV use across transport network". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "Chinese TV station CCTV provide 'old school' analysis of AFC Asian Cup match". Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- Ng, Kelly (11 October 2014). "Indian state government uses CCTV to cut forest crimes". Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "Chinese man caught by facial recognition at pop concert". British Broadcasting Corporation. 13 April 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- "Who's watching: the cities with the most CCTV cameras". Geographical. 7 March 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ Bischoff, Paul (15 August 2019). "Surveillance Camera Statistics: Which City has the Most CCTV?". Comparitech. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ "Surveillance Cities: who has the most CCTV cameras in the world?". Surfshark. November 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- Hui, Mary (21 February 2024). "China wants more control of its mass surveillance system". Quartz. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- Jankowicz, Mia (17 September 2024). "South Korea removed 1,300 cameras from its military bases after discovering they're designed to feed back to a Chinese server". Business Insider. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Police plan to put up 7,000 CCTVs in HK by 2027". Radio Television Hong Kong. 17 December 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "New CCTV cameras in Hong Kong to be equipped with facial recognition technology, security chief says". Hong Kong Free Press. 26 July 2024. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- Yeung, Jessie (6 October 2024). "Hong Kong plans to install thousands of surveillance cameras. Critics say it's more proof the city is moving closer to China". CNN. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- Leonie Helm (11 October 2024). "Hong Kong to get thousands of new security cameras – with AI and facial recognition technology". digitalcameraworld. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- Yoshino, Jiro (13 November 2018). "日本の防犯カメラ、500万台に迫る" [Japan's security cameras approach 5 million] (in Japanese). Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- "Almost 90,000 police cameras installed in Singapore, 'many more to come': Shanmugam". Yahoo News. 1 March 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Chicago's Camera Network Is Everywhere". The Wall Street Journal. 17 November 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Chicago Links Police, Private Cameras". WLS-TV. 2010. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- "Chicago's Video SURVEILLANCE CAMERAS: A PERVASIVE AND UNREGULATED THREAT TO OUR PRIVACY" (PDF). ACLU of Illinois. February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "NYPD expands surveillance net to fight crime as well as terrorism". Reuters. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- "Lack of Video Slows Hunt for a Killer in the Subway". The New York Times. 29 March 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- "The State Of Surveillance". Bloomberg Business. 7 August 2005. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- "The Building Has 1,000 Eyes". The New York Times. 4 October 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "30,000 Surveillance Cameras Monitor D.C.-Area Public Schools". NBC Washington. 1 January 2015. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- "Metro Plans to Triple Number of Security Cameras". NBC Washington. 1 April 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- Technocreep: the surrender of privacy and the capitalization of intimacy. : Greystone Books. 2014. p. 28. ISBN 978-1771641227; "Surveillance Society: New High-Tech Cameras Are Watching You". Popular Mechanics. 30 September 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2015; "Lawmakers want more surveillance on the ground -- and in the sky". NBC News. 20 April 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2015; Dempsey, John; Forst, Linda (2015). An Introduction to Policing. Cengage Learning. p. 485. ISBN 9781305544680.

- "Public Video Surveillance: Is It An Effective Crime Prevention Tool?". California Research Bureau. June 1997. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

The popularity of CCTV security systems has not gone unnoticed by the manufacturers of camera surveillance systems. ...A leading CCTV manufacturer reported net earnings of $120 million in 1995, compared with net earnings of $16 million the previous year. ...Over 50 percent of all CCTV surveillance equipment sales are to industrial and commercial clients. CCTV surveillance is also very common in the American workplace.

- Minoli, Daniel (2013). Building the internet of things with IPv6 and MIPv6 the evolving world of M2M communications. New Jersey: Wiley. p. 86. ISBN 9781118647134.

- "The great surveillance boom". Fortune. 26 April 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- "Privacy Fears Grow as Cities Increase Surveillance". The New York Times. 13 October 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Ilic-Godfrey, Stanislava (2021). "Artificial intelligence: taking on a bigger role in our future security". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- "Security Camera Registration And Monitoring (S.C.R.A.M.)". Halton Regional Police Service. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Latin American Physical Security Market Growing Rapidly". Security Magazine. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Law in Brazil". DLA Piper Global Data Protection Laws of the World. 28 January 2024. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- "Brazil: Relevant legislation" (PDF). National Protective Security Authority.

- Mari, Angelica (13 July 2023). "Facial recognition surveillance in São Paulo could worsen racism". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Moscow has one of the world's largest CCTV systems with face recognition". mos.ru. 29 September 2017.

- McGoogan, Cara (29 September 2017). "Facial recognition fitted to 5,000 CCTV cameras in Moscow". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "Шадаев сообщил, что в России работает более 1 млн камер видеонаблюдения" [Shadayev reported that there are more than 1 million CCTV cameras in operation in Russia]. TASS (in Russian). 13 March 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Создание городской системы видеонаблюдения" [Creation of a city video surveillance system]. um.mos.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 June 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- Gielewska, Anna (27 March 2024). "Kremlin Leaks: How Putin's Regime is Building AI Surveillance Operations". VSquare.org. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "The Price of Privacy: How local authorities spent £515m on CCTV in four years" (PDF). Big Brother Watch. February 2012. p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "You're being watched: there's one CCTV camera for every 32 people in UK - Research shows 1.85m machines across Britain, most of them indoors and privately operated". The Guardian. 2 March 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "CCTV in London" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- "FactCheck: how many CCTV cameras?". Channel 4 News. 18 June 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- "How many cameras are there?". CCTV User Group. 18 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- Bannister, J., Mackenzie, S. and Norris, P. Public Space CCTV in Scotland Archived 27 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine(2009), Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research (Research Report)

- "Surveillance cameras in Germany and Europe: A statistical overview". Weber Protect. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- "The story of CCTV in Europe, from resistance to adoption". www.calipsa.io. 13 January 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- "CCTV Systems". Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- "PSIRA ACT" (PDF). Private Security Industry Regulatory Authority. 25 February 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Bischoff, Paul (15 August 2019). "Surveillance Camera Statistics: Which City has the Most CCTV?". Comparitech. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Concern over violations as Egypt plans CCTV cameras in new high-tech capital". Arab Weekly. 2023. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Interior ministry restores Juba CCTV cameras". Radio Tamazuj. 30 January 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "South Sudan launches CCTV and drone system to fight crime". AfricaNews. 4 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- Kroener, Inga (2014). CCTV: A Technology Under the Radar?. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9781472400963.

- Todd Lewan (7 July 2007). "Microchips in humans spark privacy debate". USAToday. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Beatrice Von Silva-Tarouca Larsen (2011). Setting the watch: Privacy and the ethics of CCTV surveillance. Hart Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 9781849460842.

- "Your Right to Privacy". American Civil Liberties Union.

- Department of Justice - Video Surveillance Retrieved 6 August 1982

- "What's Wrong With Public Video Surveillance". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Inga Kroener (2014). CCTV: A Technology Under the Radar?. Ashgate Publishing. p. 110. ISBN 9781472400963.

- "Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. F.31". Ontario.ca. Archived from the original on 16 December 2024. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- Lahtinen, Markus (2017). "The perception of surveillance cameras and privacy among the general public in Sweden" (PDF). LUSAX-research group, Lund University School of Economics and Management, Sweden. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- "Memorandum by A A Adams, BSc, MSc, PhD, LLM, MBCS, CITP School of Systems Engineering". UK Parliament Constitution Committee - Written Evidence. Surveillance: Citizens and the State. January 2007.

- "Privacy watchdog wants curbs on surveillance". The Telegraph. 1 May 2007. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- "CCTV, computers and the 'climate of fear'". Evening Standard. 13 April 2012.

- ^ Hall, Tim (31 May 2007). "Majority of UK's CCTV cameras 'are illegal'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 June 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- Siddique, Haroon (11 December 2014). "Home surveillance CCTV images may breach data protection laws, ECJ rules". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- "Surveillance Camera Code of Practice" (PDF). UK Government Home Office. June 2013. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Manalo, Dennes M.; Mapoy, Kim Alvin; Villano, Kim Joem K.; Reyes, Kenneth Angelo D.; Bautista, Merwina Lou A. (2015). "Status of Closed Circuit Television Camera Usage in Batangas City: Basis for Enhancement" (PDF). College of Criminology Research Journal. 6 – via Pubatangas.

- "Republic Act 10173 - Data Privacy Act of 2012". National Privacy Commission.

- "Republic Act No. 10175 | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- Vincent, James (23 January 2018). "Artificial intelligence is going to supercharge surveillance". The Verge. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- 2018 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS) : 3-5 April 2018, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan. Jordan University of Science & Technology, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Jordan Section, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Piscataway, New Jersey. 2018. ISBN 9781538643662.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - "MATE's Analytics Integrate with Hirsch Security Systems". Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- "Image Processing Techniques for Video Content Extraction" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Indra Bayu Pangestu; Maimunah, Maimunah; Mukhtar Hanafi (30 September 2024). "Traffic Congestion Detection Using YOLOv8 Algorithm With CCTV Data". PIKSEL: Penelitian Ilmu Komputer Sistem Embedded and Logic. 12 (2): 435–444. doi:10.33558/piksel.v12i2.9953. ISSN 2620-3553.

- "Korean researchers develop AI CCTVs to detect, predict criminal activities". Tech Explore. 12 September 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "MotionJPEG, JPEG2000, H.264 and MPEG-4 compression methods in CCTV". Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Global value of IP camera sales now close to 50% of CCTV cameras sold, but..." Network Webcams. 19 December 2013.

- "Remote Escort". Securitas. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- "Securing IP Surveillance Cameras in the IoT Ecosystem - Noticias de seguridad - Trend Micro MX". www.trendmicro.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "Selecting the most suitable cameras to monitor large areas". internationalsecurityjournal.com. International Security Journal. 19 November 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- "ONVIF: a guide to the open security platform". ifsecglobal.com. IFSEC Global. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- "Dispelling the Top 10 Myths of IP Surveillance" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "The City of Chicago's OEMC and IBM Launch Advanced Video Surveillance System". IBM News Room. Archived from the original on 24 May 2009.

- William M. Bulkeley. "Chicago's Camera Network Is Everywhere". Wall Street Journal.

- "Chicago's Camera Network Is Everywhere", The Wall Street Journal

- "CCTV Camera Installation Guide". iS3 Tech. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- Sadun, Erica (26 December 2006). Digital Video Essentials: Shoot, Transfer, Edit, Share By Erica Sadun. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470113196. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Caputo, Tony C. (2010). Digital video surveillance and security. Burlington, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-0-08-096169-9.

- "Town trials talking CCTV cameras". BBC News. 17 September 2006.

- "'Talking' CCTV cameras are tested". BBC News. 25 March 2007.

- "Be Seen and Unseen! Reflectacles are the Sunglasses of the Future". Magnetic Magazine. 29 December 2016. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017.

- "Reflectacles - Reflective Eyewear and Sunglasses". Kickstarter. 22 July 2019.

Further reading

- Armstrong, Gary, ed. (1999). The maximum surveillance society: the rise of CCTV. Berg (originally, University of Michigan Press). ISBN 9781859732212.

- Fyfe, Nicholas; Bannister, Jon (2005). "City Watching: Closed-Circuit Television in Public Spaces". In Fyfe, Nicholas; Kenny, Judith T. (eds.). The Urban Geography Reader. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415307017.

- Nassauer, Anne (2018). "How Robberies Succeed or Fail: Analyzing Crime Caught on CCTV". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 55 (1): 125–154. doi:10.1177/0022427817715754.

- Newburn, Tim; Hayman, Stephanie (2001). Policing, Surveillance and Social Control: CCTV and police monitoring of suspects. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781843924692.

- Norris, Clive (2003). "From Personal to Digital: CCTV, the panopticon, and the technological mediation of suspicion and social control". In Lyon, David (ed.). Surveillance as Social Sorting: Privacy, Risk, and Digital Discrimination. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415278737.

- Wei Qi Yan (2019). Introduction to Intelligent Surveillance: Surveillance Data Capture, Transmission, and Analytics, Springer London.