| This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (June 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

| Healthcare in Canada |

|---|

|

| Health Canada |

| History of medicine |

| Topics |

|

|

| Healthcare cost per person. US dollars PPP. | |

|---|---|

| Canada | $6,319 (2022) |

| USA | $12,555 (2022) |

| Life expectancy. 2021 | |

|---|---|

| Canada | 82.6 years |

| USA | 76.3 years |

| Maternal mortality rate per 100,000 births | |

|---|---|

| Canada | 11 (2020) |

| USA | 33 (2021) |

| Under-5 mortality rate per 1000 live births. 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Canada | 5.0 |

| USA | 6.3 |

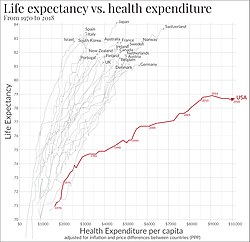

A comparison of the healthcare systems in Canada and the United States is often made by government, public health and public policy analysts. The two countries had similar healthcare systems before Canada changed its system in the 1960s and 1970s. The United States spends much more money on healthcare than Canada, on both a per-capita basis and as a percentage of GDP. In 2006, per-capita spending for health care in Canada was US$3,678; in the U.S., US$6,714. The U.S. spent 15.3% of GDP on healthcare in that year; Canada spent 10.0%. In 2006, 70% of healthcare spending in Canada was financed by government, versus 46% in the United States. Total government spending per capita in the U.S. on healthcare was 23% higher than Canadian government spending. U.S. government expenditure on healthcare was just under 83% of total Canadian spending (public and private).

Studies have come to different conclusions about the result of this disparity in spending. A 2007 review of all studies comparing health outcomes in Canada and the US in a Canadian peer-reviewed medical journal found that "health outcomes may be superior in patients cared for in Canada versus the United States, but differences are not consistent." Some of the noted differences were a higher life expectancy in Canada, as well as a lower infant mortality rate than the United States.

One commonly cited comparison, the 2000 World Health Organization's ratings of "overall health service performance", which used a "composite measure of achievement in the level of health, the distribution of health, the level of responsiveness and fairness of financial contribution", ranked Canada 30th and the US 37th among 191 member nations. This study rated the US "responsiveness", or quality of service for individuals receiving treatment, as 1st, compared with 7th for Canada. However, the average life expectancy for Canadians was 80.34 years compared with 78.6 years for residents of the US.

The WHO's study methods were criticized by some analyses. While life-expectancy and infant mortality are commonly used in comparing nationwide health care, they are in fact affected by many factors other than the quality of a nation's health care system, including individual behavior and population makeup. A 2007 report by the Congressional Research Service carefully summarizes some recent data and noted the "difficult research issues" facing international comparisons.

Government involvement

In 2004, government funding of healthcare in Canada was equivalent to $1,893 per person. In the US, government spending per person was $2,728.

The Canadian healthcare system is composed of at least 10 mostly autonomous provincial healthcare systems that report to their provincial governments, and a federal system which covers the military and First Nations. This causes a significant degree of variation in funding and coverage within the country.

History

Canada and the US had similar healthcare systems in the early 1960s, but now have a different mix of funding mechanisms. Canada's universal single-payer healthcare system covers about 70% of expenditures, and the Canada Health Act requires that all insured persons be fully insured, without co-payments or user fees, for all medically necessary hospital and physician care. About 91% of hospital expenditures and 99% of total physician services are financed by the public sector. In the United States, with its mixed public-private system, 16% or 45 million American residents are uninsured at any one time. The U.S. is one of two OECD countries not to have some form of universal health coverage, the other being Turkey. Mexico established a universal healthcare program by November 2008.

Health insurance

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The governments of both nations are closely involved in healthcare. The central structural difference between the two is in health insurance. In Canada, the federal government is committed to providing funding support to its provincial governments for healthcare expenditures as long as the province in question abides by accessibility guarantees as set out in the Canada Health Act, which explicitly prohibits billing end users for procedures that are covered by Medicare. While some label Canada's system as "socialized medicine", health economists do not use that term. Unlike systems with public delivery, such as the UK, the Canadian system provides public coverage for a combination of public and private delivery. Princeton University health economist Uwe E. Reinhardt says that single-payer systems are not "socialized medicine" but "social insurance" systems, since providers (such as doctors) are largely in the private sector. Similarly, Canadian hospitals are controlled by private boards or regional health authorities, rather than being part of government.

In the US, direct government funding of health care is limited to Medicare, Medicaid, and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), which cover eligible senior citizens, the poor, disabled persons, and children. The federal government also runs the Veterans Health Administration, which provides care directly to retired or disabled veterans, their families, and survivors through medical centers and clinics.

The U.S. government also runs the Military Health System. In fiscal year 2007, the MHS had a total budget of $39.4 billion and served approximately 9.1 million beneficiaries, including active-duty personnel and their families, and retirees and their families. The MHS includes 133,000 personnel, 86,000 military and 47,000 civilian, working at more than 1,000 locations worldwide, including 70 inpatient facilities and 1,085 medical, dental, and veterans' clinics.

One study estimates that about 25 percent of the uninsured in the U.S. are eligible for these programs but remain unenrolled; however, extending coverage to all who are eligible remains a fiscal and political challenge.

For everyone else, health insurance must be paid for privately. Some 59% of U.S. residents have access to health care insurance through employers, although this figure is decreasing, and coverages as well as workers' expected contributions vary widely. Those whose employers do not offer health insurance, as well as those who are self-employed or unemployed, must purchase it on their own. Nearly 27 million of the 45 million uninsured U.S. residents worked at least part-time in 2007, and more than a third were in households that earned $50,000 or more per year.

Funding

Despite the greater role of private business in the US, federal and state agencies are increasingly involved, paying about 45% of the $2.2 trillion the nation spent on medical care in 2004. The U.S. government spends more on healthcare than on Social Security and national defense combined, according to the Brookings Institution.

Beyond its direct spending, the US government is also highly involved in healthcare through regulation and legislation. For example, the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 provided grants and loans to subsidize Health Maintenance Organizations and contained provisions to stimulate their popularity. HMOs had been declining before the law; by 2002 there were 500 such plans enrolling 76 million people.

The Canadian system has been 69–75% publicly funded, though most services are delivered by private providers, including physicians (although they may derive their revenue primarily from government billings). Although some doctors work on a purely fee-for-service basis (usually family physicians), some family physicians and most specialists are paid through a combination of fee-for-service and fixed contracts with hospitals or health service management organizations.

Canada's universal health plans do not cover certain services. Non-cosmetic dental care is covered for children up to age 14 in some provinces. Outpatient prescription drugs are not required to be covered, but some provinces have drug cost programs that cover most drug costs for certain populations. In every province, seniors receiving the Guaranteed Income Supplement have significant additional coverage; some provinces expand forms of drug coverage to all seniors, low-income families, those on social assistance, or those with certain medical conditions. Some provinces cover all drug prescriptions over a certain portion of a family's income. Drug prices are also regulated, so brand-name prescription drugs are often significantly cheaper than in the U.S. Optometry is covered in some provinces and is sometimes covered only for children under a certain age. Visits to non-physician specialists may require an additional fee. Also, some procedures are only covered under certain circumstances. For example, circumcision is not covered, and a fee is usually charged when a parent requests the procedure; however, if an infection or medical necessity arises, the procedure would be covered.

According to Dr. Albert Schumacher, former president of the Canadian Medical Association, an estimated 75 percent of Canadian healthcare services are delivered privately, but funded publicly.

Frontline practitioners whether they're GPs or specialists by and large are not salaried. They're small hardware stores. Same thing with labs and radiology clinics ... The situation we are seeing now are more services around not being funded publicly but people having to pay for them, or their insurance companies. We have sort of a passive privatization.

Coverage and access

There is a significant difference in coverage for medical care in Canada and the United States. In Canada, all citizens and permanent residents are covered by the health care system, while in the United States, studies suggest that 7% of U.S. citizens do not have adequate health insurance, if any at all.

In both Canada and the United States, access can be a problem. In Canada, 5% of Canadian residents have not been able to find a regular doctor, with a further 9% having never looked for one. In such cases, however, they continue to have coverage for options such as walk-in clinics or emergency rooms. The U.S. data is evidenced in a 2007 Consumer Reports study on the U.S. health care system which showed that the underinsured account for 4% of the U.S. population and live with skeletal health insurance that barely covers their medical needs and leaves them unprepared to pay for major medical expenses. The Canadian data comes from the 2003 Canadian Community Health Survey,

In the U.S., the federal government does not guarantee universal healthcare to all its citizens, but publicly funded healthcare programs help to provide for the elderly, disabled, the poor, and children. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act or EMTALA also ensures public access to emergency services. The EMTALA law forces emergency healthcare providers to stabilize an emergency health crisis and cannot withhold treatment for lack of evidence of insurance coverage or other evidence of the ability to pay. EMTALA does not absolve the person receiving emergency care of the obligation to meet the cost of emergency healthcare not paid for at the time and it is still within the right of the hospital to pursue any debtor for the cost of emergency care provided. In Canada, emergency room treatment for legal Canadian residents is not charged to the patient at time of service but is met by the government.

According to the United States Census Bureau, 59.3% of U.S. citizens have health insurance related to employment, 27.8% have government-provided health-insurance; nearly 9% purchase health insurance directly (there is some overlap in these figures), and 15.3% (45.7 million) were uninsured in 2007. An estimated 25 percent of the uninsured are eligible for government programs but unenrolled. About a third of the uninsured are in households earning more than $50,000 annually. A 2003 report by the Congressional Budget Office found that many people lack health insurance only temporarily, such as after leaving one employer and before a new job. The number of chronically uninsured (uninsured all year) was estimated at between 21 and 31 million in 1998. Another study, by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, estimated that 59 percent of uninsured adults have been uninsured for at least two years. One indicator of the consequences of Americans' inconsistent health care coverage is a study in Health Affairs that concluded that half of personal bankruptcies involved medical bills. Although other sources dispute this, it is possible that medical debt is the principal cause of bankruptcy in the United States.

A number of clinics provide free or low-cost non-emergency care to poor, uninsured patients. The National Association of Free Clinics claims that its member clinics provide $3 billion in services to some 3.5 million patients annually.

A peer-reviewed comparison study of healthcare access in the two countries published in 2006 concluded that U.S. residents are one third less likely to have a regular medical doctor (80% vs 85%), one fourth more likely to have unmet healthcare needs (13% vs 11%), and are more than twice as likely to forgo needed medicines (1.7% vs 2.6%). The study noted that access problems "were particularly dire for the US uninsured." Those who lack insurance in the U.S. were much less satisfied, less likely to have seen a doctor, and more likely to have been unable to receive desired care than both Canadians and insured Americans.

Another cross-country study compared access to care based on immigrant status in Canada and the U.S. Findings showed that in both countries, immigrants had worse access to care than non-immigrants. Specifically, immigrants living in Canada were less likely to have timely Pap tests compared with native-born Canadians; in addition, immigrants in the U.S. were less likely to have a regular medical doctor and an annual consultation with a health care provider compared with native-born Americans. In general, immigrants in Canada had better access to care than those in the U.S., but most of the differences were explained by differences in socioeconomic status (income, education) and insurance coverage across the two countries. However, immigrants in the U.S. were more likely to have timely Pap tests than immigrants in Canada.

Cato Institute has expressed concerns that the U.S. government has restricted the freedom of Medicare patients to spend their own money on healthcare, and has contrasted these developments with the situation in Canada, where in 2005 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the province of Quebec could not prohibit its citizens from purchasing covered services through private health insurance. The institute has urged the Congress to restore the right of American seniors to spend their own money on medical care.

Coverage for mental health

The Canada Health Act covers the services of psychiatrists, who are medical doctors with additional training in psychiatry but does not cover treatment by a psychologist or psychotherapist unless the practitioner is also a medical doctor. Goods and Services Tax or Harmonized Sales Tax (depending on the province) applies to the services of psychotherapists. Some provincial or territorial programs and some private insurance plans may cover the services of psychologists and psychotherapists, but there is no federal mandate for such services in Canada. In the U.S., the Affordable Care Act includes prevention, early intervention, and treatment of mental and/or substance use disorders as an "essential health benefit" (EHB) that must be covered by health plans that are offered through the Health Insurance Marketplace. Under the Affordable Care Act, most health plans must also cover certain preventive services without a copayment, co-insurance, or deductible. In addition, the U.S. Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008 mandates "parity" between mental health and/or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) benefits and medical/surgical benefits covered by a health plan. Under that law, if a health care plan offers mental health and/or substance use disorder benefits, it must offer the benefits on par with the other medical/surgical benefits it covers.

Wait times

One complaint about both the U.S. and Canadian systems is waiting times, whether for a specialist, major elective surgery, such as hip replacement, or specialized treatments, such as radiation for breast cancer; wait times in each country are affected by various factors. In the United States, access is primarily determined by whether a person has access to funding to pay for treatment and by the availability of services in the area and by the willingness of the provider to deliver service at the price set by the insurer. In Canada, the wait time is set according to the availability of services in the area and by the relative need of the person needing treatment.

As reported by the Health Council of Canada, a 2010 Commonwealth survey found that 39% of Canadians waited 2 hours or more in the emergency room, versus 31% in the U.S.; 43% waited 4 weeks or more to see a specialist, versus 10% in the U.S. The same survey states that 37% of Canadians say it is difficult to access care after hours (evenings, weekends or holidays) without going to the emergency department compared to over 34% of Americans. Furthermore, 47% of Canadians and 50% of Americans who visited emergency departments over the past two years feel that they could have been treated at their normal place of care if they were able to get an appointment.

A 2018 survey conducted by the Fraser Institute, a conservative-libertarian public policy think tank, found that wait times in Canada for a variety of medical procedures reached "an all-time high". Appointment duration (meeting with physicians) averaged under two minutes. These very fast appointments are a result of physicians attempting to accommodate for the number of patients using the medical system. In these appointments, however, diagnoses or prescriptions were rarely given, where the patients instead were almost always referred to specialists to receive treatment for their medical issues. According to the Fraser Institute, patients in Canada waited an average of 19.8 weeks to receive treatment, regardless of whether they were able to see a specialist or not. In the U.S., the average wait time for a first-time appointment is 24 days (≈3 times faster than in Canada); wait times for Emergency Room (ER) services averaged 24 minutes (more than 4x faster than in Canada); wait times for specialists averaged between 3–6.4 weeks (over 6x faster than in Canada). In response to these findings, the Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), an advocacy organization comprising more than 20,000 American medical professionals, identified statistical problems with the Fraser Institute's reporting. Namely, the report relies on a survey of Canadian physicians with a response rate of only 15.8%. Distributing these responses amongst the 12 specialties and ten provinces results in single-digit tallies for 63 per cent of the categories, and often only one physician falling into a given category. Conversely, a study conducted by the Canadian Institute for Health Information indicated that Canada has been successful in delivering care within medically recommended wait times.

In the U.S., patients on Medicaid, the low-income government programs, can wait up to a maximum of 12 weeks to see specialists (12 weeks less than the average wait time in Canada). Because Medicaid payments are low, some have claimed that some doctors do not want to see Medicaid patients in Canada. For example, in Benton Harbor, Michigan, specialists agreed to spend one afternoon every week or two at a Medicaid clinic, which meant that Medicaid patients had to make appointments not at the doctor's office, but at the clinic, where appointments had to be booked months in advance. A 2009 study found that on average the wait in the United States to see a medical specialist is 20.5 days.

In a 2009 survey of physician appointment wait times in the United States, the average wait time for an appointment with an orthopedic surgeon in the country as a whole was 17 days. In Dallas, Texas the wait was 45 days (the longest wait being 365 days). Nationwide across the U.S. the average wait time to see a family doctor was 20 days. The average wait time to see a family practitioner in Los Angeles, California was 59 days and in Boston, Massachusetts it was 63 days.

Studies by the Commonwealth Fund found that 42% of Canadians waited 2 hours or more in the emergency room, vs. 29% in the U.S.; 57% waited 4 weeks or more to see a specialist, vs. 23% in the U.S., but Canadians had more chances of getting medical attention at nights, or on weekends and holidays than their American neighbors without the need to visit an ER (54% compared to 61%). Statistics from the Fraser Institute in 2008 indicate that the average wait time between the time when a general practitioner refers a patient for care and the receipt of treatment was almost four and a half months in 2008, roughly double what it had been 15 years before.

A 2003 survey of hospital administrators conducted in Canada, the U.S., and three other countries found dissatisfaction with both the U.S. and Canadian systems. For example, 21% of Canadian hospital administrators, but less than 1% of American administrators, said that it would take over three weeks to do a biopsy for possible breast cancer on a 50-year-old woman; 50% of Canadian administrators versus none of their American counterparts said that it would take over six months for a 65-year-old to undergo a routine hip replacement surgery. However, U.S. administrators were the most negative about their country's system. Hospital executives in all five countries expressed concerns about staffing shortages and emergency department waiting times and quality.

In a letter to The Wall Street Journal, Robert Bell, the President and CEO of University Health Network, Toronto, said that Michael Moore's film Sicko "exaggerated the performance of the Canadian health system — there is no doubt that too many patients still stay in our emergency departments waiting for admission to scarce hospital beds." However, "Canadians spend about 55% of what Americans spend on health care and have longer life expectancy and lower infant mortality rates. Many Americans have access to quality healthcare. All Canadians have access to similar care at a considerably lower cost." There is "no question" that the lower cost has come at the cost of "restriction of supply with sub-optimal access to services," said Bell. A new approach is targeting waiting times, which are reported on public websites.

In 2007, Shona Holmes, a Waterdown, Ontario woman who had a Rathke's cleft cyst removed at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona, sued the Ontario government for failing to reimburse her $95,000 in medical expenses. Holmes had characterized her condition as an emergency, said she was losing her sight and portrayed her condition as a life-threatening brain cancer. In July 2009 Holmes agreed to appear in television ads broadcast in the United States warning Americans of the dangers of adopting a Canadian-style health care system. The ads she appeared in triggered debates on both sides of the border. After her ad appeared critics pointed out discrepancies in her story, including that Rathke's cleft cyst, the condition she was treated for, was not a form of cancer, and was not life-threatening.

Price of health care and administration overheads

Healthcare is one of the most expensive items of both nations' budgets. In the United States, the various levels of government spend more per capita than levels of government do in Canada. In 2004, Canada government-spending was $2,120 (in US dollars) per person, while the United States government-spending was $2,724.

Administrative costs are also higher in the United States than in Canada. A 1999 report found that after exclusions, administration accounted for 31.0% of healthcare expenditures in the United States, as compared with 16.7% in Canada. In looking at the insurance element, in Canada, the provincial single-payer insurance system operated with overheads of 1.3%, comparing favourably with private insurance overheads (13.2%), U.S. private insurance overheads (11.7%) and U.S. Medicare and Medicaid program overheads (3.6% and 6.8% respectively). The report concluded by observing that gap between U.S. and Canadian spending on administration had grown to $752 per capita and that a large sum might be saved in the United States if the U.S. implemented a Canadian-style system.

However, U.S. government spending covers less than half of all healthcare costs. Private spending is also far greater in the U.S. than in Canada. In Canada, an average of $917 was spent annually by individuals or private insurance companies for health care, including dental, eye care, and drugs. In the U.S., this sum is $3,372. In 2006, healthcare consumed 15.3% of U.S. annual GDP. In Canada, 10% of GDP was spent on healthcare. This difference is a relatively recent development. In 1971 the nations were much closer, with Canada spending 7.1% of GDP while the U.S. spent 7.6%.

Some who advocate against greater government involvement in healthcare have asserted that the difference in costs between the two nations is partially explained by the differences in their demographics. Illegal immigrants, more prevalent in the U.S. than in Canada, also add a burden to the system, as many of them do not carry health insurance and rely on emergency rooms — which are legally required to treat them under EMTALA — as a principal source of care. In Colorado, for example, an estimated 80% of undocumented immigrants do not have health insurance.

Through all entities in its public–private system, the US spends more per capita than any other nation in the world, but is the only wealthy industrialized country in the world that lacks some form of universal healthcare. In March 2010, the US Congress passed regulatory reform of the American 'health insurance system. However, since this legislation is not fundamental healthcare reform, it is unclear what its effect will be and as the new legislation is implemented in stages, with the last provision in effect in 2018, it will be some years before any empirical evaluation of the full effects on the comparison could be determined.

Healthcare costs in both countries are rising faster than inflation. As both countries consider changes to their systems, there is debate over whether resources should be added to the public or private sector. Although Canadians and Americans have each looked to the other for ways to improve their respective health care systems, there exists a substantial amount of conflicting information regarding the relative merits of the two systems. In the U.S., Canada's mostly monopsonistic health system is seen by different sides of the ideological spectrum as either a model to be followed or avoided.

Medical professionals

Some of the extra money spent in the United States goes to physicians, nurses, and other medical professionals. According to health data collected by the OECD, average income for physicians in the United States in 1996 was nearly twice that for physicians in Canada. In 2012, the gross average salary for doctors in Canada was CDN$328,000. Out of the gross amount, doctors pay for taxes, rent, staff salaries and equipment. In Canada, less than half of doctors are specialists whereas more than 70% of doctors are specialists in the U.S.

Canada has fewer doctors per capita than the United States. In the U.S, there were 2.4 doctors per 1,000 people in 2005; in Canada, there were 2.2. Some doctors leave Canada to pursue career goals or higher pay in the U.S., though significant numbers of physicians from countries such as China, India, Pakistan and South Africa immigrate to practice in Canada. Many Canadian physicians and new medical graduates also go to the U.S. for post-graduate training in medical residencies. As it is a much larger market, new and cutting-edge sub-specialties are more widely available in the U.S. as opposed to Canada. However, statistics published in 2005 by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), show that, for the first time since 1969 (the period for which data are available), more physicians returned to Canada than moved abroad.

Drugs

Both Canada and the United States have limited programs to provide prescription drugs to the needy. In the U.S., the introduction of Medicare Part D has extended partial coverage for pharmaceuticals to Medicare beneficiaries. In Canada all drugs given in hospitals fall under Medicare, but other prescriptions do not. The provinces all have some programs to help the poor and seniors have access to drugs, but while there have been calls to create one, no national program exists. About two thirds of Canadians have private prescription drug coverage, mostly through their employers. In both countries, there is a significant population not fully covered by these programs. A 2005 study found that 20% of Canada's and 40% of America's sicker adults did not fill a prescription because of cost.

Furthermore, the 2010 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey indicates that 4% of Canadians indicated that they did not visit a doctor because of cost compared with 22% of Americans. Additionally, 21% of Americans have said that they did not fill a prescription for medicine or have skipped doses due to cost. That is compared with 10% of Canadians.

One of the most important differences between the two countries is the much higher cost of drugs in the United States. In the U.S., $728 per capita is spent each year on drugs, while in Canada it is $509. At the same time, consumption is higher in Canada, with about 12 prescriptions being filled per person each year in Canada and 10.6 in the United States. The main difference is that patented drug prices in Canada average between 35% and 45% lower than in the United States, though generic prices are higher. The price differential for brand-name drugs between the two countries has led Americans to purchase upward of $1 billion US in drugs per year from Canadian pharmacies.

There are several reasons for the disparity. The Canadian system takes advantage of centralized buying by the provincial governments that have more market heft and buy in bulk, lowering prices. By contrast, the U.S. has explicit laws that prohibit Medicare or Medicaid from negotiating drug prices. In addition, price negotiations by Canadian health insurers are based on evaluations of the clinical effectiveness of prescription drugs, allowing the relative prices of therapeutically similar drugs to be considered in context. The Canadian Patented Medicine Prices Review Board also has the authority to set a fair and reasonable price on patented products, either comparing it to similar drugs already on the market, or by taking the average price in seven developed nations. Prices are also lowered through more limited patent protection in Canada. In the U.S., a drug patent may be extended five years to make up for time lost in development. Some generic drugs are thus available on Canadian shelves sooner.

The pharmaceutical industry is important in both countries, though both are net importers of drugs. Both countries spend about the same amount of their GDP on pharmaceutical research, about 0.1% annually

Technology

The United States spends more on technology than Canada. In a 2004 study on medical imaging in Canada, it was found that Canada had 4.6 MRI scanners per million population while the U.S. had 19.5 per million. Canada's 10.3 CT scanners per million also ranked behind the U.S., which had 29.5 per million. The study did not attempt to assess whether the difference in the number of MRI and CT scanners had any effect on the medical outcomes or were a result of overcapacity but did observe that MRI scanners are used more intensively in Canada than either the U.S. or Great Britain. This disparity in the availability of technology, some believe, results in longer wait times. In 1984 wait times of up to 22 months for an MRI were alleged in Saskatchewan. However, according to more recent official statistics (2007), all emergency patients receive MRIs within 24 hours, those classified as urgent receive them in under 3 weeks and the maximum elective wait time is 19 weeks in Regina and 26 weeks in Saskatoon, the province's two largest metropolitan areas.

According to the Health Council of Canada's 2010 report "Decisions, Decisions: Family doctors as gatekeepers to prescription drugs and diagnostic imaging in Canada", the Canadian federal government invested $3 billion over 5 years (2000–2005) in relation to diagnostic imaging and agreed to invest a further $2 billion to reduce wait times. These investments led to an increase in the number of scanners across Canada as well as the number of exams being performed. The number of CT scanners increased from 198 to 465 and MRI scanners increased from 19 to 266 (more than tenfold) between 1990 and 2009. Similarly, the number of CT exams increased by 58% and MRI exams increased by 100% between 2003 and 2009. In comparison to other OECD countries, including the US, Canada's rates of MRI and CT exams falls somewhere in the middle. Nevertheless, the Canadian Association of Radiologists claims that as many as 30% of diagnostic imaging scans are inappropriate and contribute no useful information.

Malpractice litigation

The extra cost of malpractice lawsuits is a proportion of health spending in both the U.S. (1.7% in 2002) and Canada (0.27% in 2001 or $237 million). In Canada the total cost of settlements, legal fees, and insurance comes to $4 per person each year, but in the United States it is over $16. Average payouts to American plaintiffs were $265,103, while payouts to Canadian plaintiffs were somewhat higher, averaging $309,417. However, malpractice suits are far more common in the U.S., with 350% more suits filed each year per person. While malpractice costs are significantly higher in the U.S., they constitute a small proportion of total medical spending. The total cost of defending and settling malpractice lawsuits in the U.S. in 2004 was over $28 billion. Critics say that defensive medicine consumes up to 9% of American healthcare expenses., but CBO studies suggest that it is much smaller.

Ancillary expenses

There are a number of ancillary costs that are higher in the U.S. Administrative costs are significantly higher in the U.S.; government mandates on record keeping and the diversity of insurers, plans and administrative layers involved in every transaction result in greater administrative effort. One recent study comparing administrative costs in the two countries found that these costs in the U.S. are roughly double what they are in Canada. Another ancillary cost is marketing, both by insurance companies and health care providers. These costs are higher in the U.S., contributing to higher overall costs in that nation.

Healthcare outcomes

In the World Health Organization's rankings of healthcare system performance among 191 member nations published in 2000, Canada ranked 30th and the U.S. 37th, while the overall health of Canadians was ranked 35th and Americans 72nd. However, the WHO's methodologies, which attempted to measure how efficiently health systems translate expenditure into health, generated broad debate and criticism.

Researchers caution against inferring healthcare quality from some health statistics. June O'Neill and Dave O'Neill point out that "... life expectancy and infant mortality are both poor measures of the efficacy of a health care system because they are influenced by many factors that are unrelated to the quality and accessibility of medical care".

In 2007, Gordon H. Guyatt et al. conducted a meta-analysis, or systematic review, of all studies that compared health outcomes for similar conditions in Canada and the U.S., in Open Medicine, an open-access peer-reviewed Canadian medical journal. They concluded, "Available studies suggest that health outcomes may be superior in patients cared for in Canada versus the United States, but differences are not consistent." Guyatt identified 38 studies addressing conditions including cancer, coronary artery disease, chronic medical illnesses and surgical procedures. Of 10 studies with the strongest statistical validity, 5 favoured Canada, 2 favoured the United States, and 3 were equivalent or mixed. Of 28 weaker studies, 9 favoured Canada, 3 favoured the United States, and 16 were equivalent or mixed. Overall, results for mortality favoured Canada with a 5% advantage, but the results were weak and varied. The only consistent pattern was that Canadian patients fared better in kidney failure.

In terms of population health, life expectancy in 2006 was about two and a half years longer in Canada, with Canadians living to an average of 79.9 years and Americans 77.5 years. Infant and child mortality rates are also higher in the U.S. Some comparisons suggest that the American system underperforms Canada's system as well as those of other industrialized nations with universal coverage. For example, a ranking by the World Health Organization of health care system performance among 191 member nations, published in 2000, ranked Canada 30th and the U.S. 37th, and the overall health of Canada 35th to the American 72nd. The WHO did not merely consider health care outcomes, but also placed heavy emphasis on the health disparities between rich and poor, funding for the health care needs of the poor, and the extent to which a country was reaching the potential health care outcomes they believed were possible for that nation. In an international comparison of 21 more specific quality indicators conducted by the Commonwealth Fund International Working Group on Quality Indicators, the results were more divided. One of the indicators was a tie, and in 3 others, data was unavailable from one country or the other. Canada performed better on 11 indicators; such as survival rates for colorectal cancer, childhood leukemia, and kidney and liver transplants. The U.S. performed better on 6 indicators, including survival rates for breast and cervical cancer, and avoidance of childhood diseases such as pertussis and measles. The 21 indicators were distilled from a starting list of 1000. The authors state that, "It is an opportunistic list, rather than a comprehensive list."

Some of the difference in outcomes may also be related to lifestyle choices. The OECD found that Americans have slightly higher rates of smoking and alcohol consumption than do Canadians as well as significantly higher rates of obesity. A joint US-Canadian study found slightly higher smoking rates among Canadians. Another study found that Americans have higher rates not only of obesity, but also of other health risk factors and chronic conditions, including physical inactivity, diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

While a Canadian systematic review stated that the differences in the systems of Canada and the United States could not alone explain differences in healthcare outcomes, the study didn't consider that over 44,000 Americans die every year due to not having a single payer system for healthcare in the United States and it didn't consider the millions more that live without proper medical care due to a lack of insurance.

The United States and Canada have different racial makeups, different obesity rates and different alcoholism rates, which would likely cause the US to have a shorter average life expectancy and higher infant mortality even with equal healthcare provided. The US population is 12.2% African Americans and 16.3% Hispanic Americans (2010 Census), whereas Canada has 2.5% African Canadians and 0.97% Hispanic Canadians (2006 Census). African Americans have higher mortality rates than any other racial or ethnic group for eight of the top ten causes of death. The cancer incidence rate among African Americans is 10% higher than among European Americans. U.S. Latinos have higher rates of death from diabetes, liver disease, and infectious diseases than do non-Latinos. Adult African Americans and Latinos have approximately twice the risk as European Americans of developing diabetes. The infant mortality rates for African Americans is twice that of whites. Unfortunately, directly comparing infant mortality rates between countries is difficult, as countries have different definitions of what qualifies as an infant death.

Another issue with comparing the two systems is the baseline health of the patients for which the systems must treat. Canada's obesity rate of 14.3% is about half of that of the United States 30.6%. On average, obesity reduces life expectancy by 6–7 years.

A 2004 study found that Canada had a slightly higher mortality rate for acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) because of the more conservative Canadian approach to revascularizing (opening) coronary arteries.

Cancer

Numerous studies have attempted to compare the rates of cancer incidence and mortality in Canada and the U.S., with varying results. Doctors who study cancer epidemiology warn that the diagnosis of cancer is subjective, and the reported incidence of a cancer will rise if screening is more aggressive, even if the real cancer incidence is the same. Statistics from different sources may not be compatible if they were collected in different ways. The proper interpretation of cancer statistics has been an important issue for many years. Dr. Barry Kramer of the National Institutes of Health points to the fact that cancer incidence rose sharply over the past few decades as screening became more common. He attributes the rise to increased detection of benign early stage cancers that pose little risk of metastasizing. Furthermore, though patients who were treated for these benign cancers were at little risk, they often have trouble finding health insurance after the fact.

Cancer survival time increases with later years of diagnosis, because cancer treatment improves, so cancer survival statistics can only be compared for cohorts in the same diagnosis year. For example, as doctors in British Columbia adopted new treatments, survival time for patients with metastatic breast cancer increased from 438 days for those diagnosed in 1991–1992, to 667 days for those diagnosed in 1999–2001.

An assessment by Health Canada found that cancer mortality rates are almost identical in the two countries. Another international comparison by the National Cancer Institute of Canada indicated that incidence rates for most, but not all, cancers were higher in the U.S. than in Canada during the period studied (1993–1997). Incidence rates for certain types, such as colorectal and stomach cancer, were actually higher in Canada than in the U.S. In 2004, researchers published a study comparing health outcomes in the Anglo countries. Their analysis indicates that Canada has greater survival rates for both colorectal cancer and childhood leukemia, while the United States has greater survival rates for Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma as well as breast and cervical cancer.

A study based on data from 1978 through 1986 found very similar survival rates in both the United States and in Canada. However, a study based on data from 1993 through 1997 found lower cancer survival rates among Canadians than among Americans.

A few comparative studies have found that cancer survival rates vary more widely among different populations in the U.S. than they do in Canada. Mackillop and colleagues compared cancer survival rates in Ontario and the U.S. They found that cancer survival was more strongly correlated with socio-economic class in the U.S. than in Ontario. Furthermore, they found that the American survival advantage in the four highest quintiles was statistically significant. They strongly suspected that the difference due to prostate cancer was a result of greater detection of asymptomatic cases in the U.S. Their data indicates that neglecting the prostate cancer data reduces the American advantage in the four highest quintiles and gives Canada a statistically significant advantage in the lowest quintile. Similarly, they believe differences in screening mammography may explain part of the American advantage in breast cancer. Exclusion of breast and prostate cancer data results in very similar survival rates for both countries.

Hsing et al. found that prostate cancer mortality incidence rate ratios were lower among U.S. whites than among any of the nationalities included in their study, including Canadians. U.S. African Americans in the study had lower rates than any group except for Canadians and U.S. whites. Echoing the concerns of Dr. Kramer and Professor Mackillop, Hsing later wrote that reported prostate cancer incidence depends on screening. Among whites in the U.S., the death rate for prostate cancer remained constant, even though the incidence increased, so the additional reported prostate cancers did not represent an increase in real prostate cancers, said Hsing. Similarly, the death rates from prostate cancer in the U.S. increased during the 1980s and peaked in early 1990. This is at least partially due to "attribution bias" on death certificates, where doctors are more likely to ascribe a death to prostate cancer than to other diseases that affected the patient, because of greater awareness of prostate cancer or other reasons.

Because health status is "considerably affected" by socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, such as level of education and income, "the value of comparisons in isolating the impact of the healthcare system on outcomes is limited," according to health care analysts. Experts say that the incidence and mortality rates of cancer cannot be combined to calculate survival from cancer. Nevertheless, researchers have used the ratio of mortality to incidence rates as one measure of the effectiveness of healthcare. Data for both studies was collected from registries that are members of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, an organization dedicated to developing and promoting uniform data standards for cancer registration in North America.

Racial and ethnic differences

The U.S. and Canada differ substantially in their demographics, and these differences may contribute to differences in health outcomes between the two nations. Although both countries have white majorities, Canada has a proportionately larger immigrant minority population. Furthermore, the relative size of different ethnic and racial groups vary widely in each country. Hispanics and peoples of African descent constitute a much larger proportion of the U.S. population. Non-Hispanic North American aboriginal peoples constitute a much larger proportion of the Canadian population. Canada also has a proportionally larger South Asian and East Asian population. Also, the proportion of each population that is immigrant is higher in Canada.

A study comparing aboriginal mortality rates in Canada, the U.S. and New Zealand found that aboriginals in all three countries had greater mortality rates and shorter life expectancies than the white majorities. That study also found that aboriginals in Canada had both shorter life expectancies and greater infant mortality rates than aboriginals in the United States and New Zealand. The health outcome differences between aboriginals and whites in Canada was also larger than in the United States.

Though few studies have been published concerning the health of Black Canadians, health disparities between whites and African Americans in the U.S. have received intense scrutiny. African Americans in the U.S. have significantly greater rates of cancer incidence and mortality. Drs. Singh and Yu found that neonatal and postnatal mortality rates for African Americans are more than double the non-Hispanic white rate. This difference persisted even after controlling for household income and was greatest in the highest income quintile. A Canadian study also found differences in neonatal mortality between different racial and ethnic groups. Although Canadians of African descent had a greater mortality rate than whites in that study, the rate was somewhat less than double the white rate.

The racially heterogeneous Hispanic population in the U.S. has also been the subject of several studies. Although members of this group are significantly more likely to live in poverty than are non-Hispanic whites, they often have disease rates that are comparable to or better than the non-Hispanic white majority. Hispanics have lower cancer incidence and mortality, lower infant mortality, and lower rates of neural tube defects. Singh and Yu found that infant mortality among Hispanic sub-groups varied with the racial composition of that group. The mostly white Cuban population had a neonatal mortality rate (NMR) nearly identical to that found in non-Hispanic whites and a postnatal mortality rate (PMR) that was somewhat lower. The largely Mestizo, Mexican, Central, and South American Hispanic populations had somewhat lower NMR and PMR. The Puerto Ricans who have a mix of white and African ancestry had higher NMR and PMR rates.

Impact on economy

In 2002, automotive companies claimed that the universal system in Canada saved labour costs. In 2004, healthcare cost General Motors $5.8 billion, and increased to $7 billion. The UAW also claimed that the resulting escalating healthcare premiums reduced workers' bargaining powers.

Flexibility

In Canada, increasing demands for healthcare, due to the aging population, must be met by either increasing taxes or reducing other government programs. In the United States, under the current system, more of the burden will be taken up by the private sector and individuals.

Since 1998, Canada's successive multibillion-dollar budget surpluses have allowed a significant injection of new funding to the healthcare system, with the stated goal of reducing waiting times for treatment. However, this may be hampered by the return to deficit spending as of the 2009 Canadian federal budget.

One historical problem with the U.S. system was known as job lock, in which people become tied to their jobs for fear of losing their health insurance. This reduces the flexibility of the labor market. Federal legislation passed since the mid-1980s, particularly COBRA and HIPAA, has been aimed at reducing job lock. However, providers of group health insurance in many states are permitted to use experience rating and it remains legal in the United States for prospective employers to investigate a job candidate's health and past health claims as part of a hiring decision. Someone who has recently been diagnosed with cancer, for example, may face job lock not out of fear of losing their health insurance, but based on prospective employers not wanting to add the cost of treating that illness to their own health insurance pool, for fear of future insurance rate increases. Thus, being diagnosed with an illness can cause someone to be forced to stay in their current job.

Politics of health

Politics of each country

Canada

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In Canada, the right-wing and now defunct Reform Party and its successor, the Conservative Party of Canada considered increasing the role of the private sector in the Canadian system. Public backlash caused these plans to be abandoned, and the Conservative government that followed re-affirmed its commitment to universal public medicine.

In Canada, it was Alberta under the Conservative government that had experimented most with increasing the role of the private sector in healthcare. Measures included the introduction of private clinics allowed to bill patients for some of the cost of a procedure, as well as 'boutique' clinics offering tailored personal care for a fixed preliminary annual fee.

United States

In the U.S., President Bill Clinton attempted a significant restructuring of health care, but the effort collapsed under political pressure against it despite tremendous public support. The 2000 U.S. election saw prescription drugs become a central issue, although the system did not fundamentally change. In the 2004 U.S. election healthcare proved to be an important issue to some voters, though not a primary one.

In 2006, Massachusetts adopted a plan that vastly reduced the number of uninsured making it the state with the lowest percentage of non-insured residents in the union. It requires everyone to buy insurance and subsidizes insurance costs for lower income people on a sliding scale. Some have claimed that the state's program is unaffordable, which the state itself says is "a commonly repeated myth". In 2009, in a minor amendment, the plan did eliminate dental, hospice and skilled nursing care for certain categories of noncitizens covering 30,000 people (victims of human trafficking and domestic violence, applicants for asylum and refugees) who do pay taxes.

In July 2009, Connecticut passed into law a plan called SustiNet, with the goal of achieving health care coverage of 98% of its residents by 2014.

US President Donald Trump had declared his intent to repeal the Affordable Care Act, but was unsuccessful.

Private care

The Canada Health Act of 1984 "does not directly bar private delivery or private insurance for publicly insured services," but provides financial disincentives for doing so. "Although there are laws prohibiting or curtailing private health care in some provinces, they can be changed," according to a report in the New England Journal of Medicine. Governments attempt to control health care costs by being the sole purchasers and thus they do not allow private patients to bid up prices. Those with non-emergency illnesses such as cancer cannot pay out of pocket for time-sensitive surgeries and must wait their turn on waiting lists. According to the Canadian Supreme Court in its 2005 ruling in Chaoulli v. Quebec, waiting list delays "increase the patient's risk of mortality or the risk that his or her injuries will become irreparable." The ruling found that a Quebec provincial ban on private health insurance was unlawful, because it was contrary to Quebec's own legislative act, the 1975 Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms.

Consumer-driven healthcare

In the United States, Congress has enacted laws to promote consumer-driven healthcare with health savings accounts (HSAs), which were created by the Medicare bill signed by President George W. Bush on December 8, 2003. HSAs are designed to provide tax incentives for individuals to save for future qualified medical and retiree health expenses. Money placed in such accounts is tax-free. To qualify for HSAs, individuals must carry a high-deductible health plan (HDHP). The higher deductible shifts some of the financial responsibility for health care from insurance providers to the consumer. This shift towards a market-based system with greater individual responsibility increased the differences between the US and Canadian systems.

Some economists who have studied proposals for universal healthcare worry that the consumer driven healthcare movement will reduce the social redistributive effects of insurance that pools high-risk and low-risk people together. This concern was one of the driving factors behind a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, informally known as Obamacare, which limited the types of purchases which could be made with HSA funds. For example, as of January 1, 2011, these funds can no longer be used to buy over-the-counter drugs without a medical prescription.

See also

- Tommy Douglas (1904–1986), considered the "Father of Canadian Medicare"

- Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010

- Health care systems (including international comparisons)

- Health care in Canada

- Healthcare in the European Union

- Health care in the United States

- Health spending as percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by country

- List of countries by total health expenditure per capita

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

- Universal health care

References

- ^ OECD Data. Health resources - Health spending. doi:10.1787/8643de7e-en. 2 bar charts: For both: From bottom menus: Countries menu > choose OECD. Check box for "latest data available". Perspectives menu > Check box to "compare variables". Then check the boxes for government/compulsory, voluntary, and total. Click top tab for chart (bar chart). For GDP chart choose "% of GDP" from bottom menu. For per capita chart choose "US dollars/per capita". Click fullscreen button above chart. Click "print screen" key. Click top tab for table, to see data.

- Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2021. From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ Szick S, Angus DE, Nichol G, Harrison MB, Page J, Moher D. "Health Care Delivery in Canada and the United States: Are There Relevant Differences in Health Care Outcomes?" Archived August 31, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, June 1999. (Publication no. 99-04-TR.)

- Esmail N, Walker M. "How good is Canadian Healthcare?: 2005 Report." Archived June 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Fraser Institute July 2005, Vancouver BC.

- Nair C, Karim R, Nyers C (1992). "Health care and health status. A Canada—United States statistical comparison". Health Reports. 4 (2): 175–83. PMID 1421020.

- "Canadian health care quality comparable to other rich countries". Archived December 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Kinch T. "Tyler Kinch: Constructing Canada: The 2007-2010 United States health care reform debate and the construction of knowledge about Canada’s single payer health care system" Archived October 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine April 2012.

- ^ "OECD Health Data 2008: How Does Canada Compare" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- World Health Organization, Core Health Indicators Archived April 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. U.S. government spending was US$2724 vs. US$2214 on a purchasing power parity basis ($2724 and $2121 on a non-adjusted basis); total U.S. spending was US$6096 vs. US$3137 (PPP) ($6096 and $3038 on a non-adjusted basis).

- ^ Guyatt G.H.; et al. (2007). "A systematic review of studies comparing health outcomes in Canada and the United States". Open Medicine. 1 (1): e27-36. PMC 2801918. PMID 20101287. Archived from the original on July 5, 2007.

- ^ "Health system attainment and performance in all Member States, ranked by eight measures, estimates for 1997" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ^ O'Neill, June E.; O'Neill, Dave M. (2008). "Health Status, Health Care and Inequality: Canada vs. the U.S." (PDF). Forum for Health Economics & Policy. 10 (1). doi:10.2202/1558-9544.1094. S2CID 73172486. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- Congressional Research Service, "U.S. Health Care Spending: Comparison with Other OECD Countries" Archived January 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, September 17, 2007. Order Code RL34175

- "Comparison with Other OECD Countries" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 26, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "The Canada Health Act: Overview and Options". Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- "The National Coalition on Health Care, Facts About Healthcare – Health Insurance Coverage". Archived from the original on August 22, 2007.

- Docteur, Elizabeth (June 23, 2003). "Reforming Health Systems in OECD Countries" (PDF). Presentation, OECD Breakfast Series in Partnership with NABE. OECD. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- Reinhardt, U.E.; et al. (July 11, 2007). "Letters: For Children's Sake, This 'Schip' Needs to Be Relaunched". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. The Wall Street Journal, July 11, 2007.

- Healthcare in Canada.

- Office, VA History. "VA History Office". www.va.gov. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- "About the Military Health System". Military Health System. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "Characteristics of the Uninsured: Who is Eligible for Public Coverage and Who Needs Help Affording Coverage?" (PDF). Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. January 30, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ "Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2007" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- Appleby, Julie (October 16, 2006). "Universal care appeals to USA". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 20, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- "Meeting the Dilemma of Health Care Access". Opportunity 08: A Project of the Brookings Institution. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- "Health Care Expenditures in the USA". National Center for Health Statistics. Medical News Today. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2007.

- "OECD Health Data 2007 – Frequently Requested Data" (Excel). OECD. Archived from the original on November 14, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- "CoverMe Government Health Insurance Coverage". Coverme.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "CoverMe Government Health Insurance Coverage". Coverme.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "CoverMe Government Health Insurance Coverage". Coverme.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "Health – Prescription Drug Program". Gnb.ca. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "Manitoba Pharmacare Program Information: 2007–2008". Province of Manitoba. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- "Why Drugs Cost Less Up North: Important Differences in American, Canadian Systems Produce Big Price Disparities". AARP Bulletin. June 2003. Archived from the original on June 7, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- "Manitoba Health Benefits". Gov.mb.ca. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- Public vs. private health care. Archived August 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine CBC, December 1, 2006.

- Canadian Community Health Survey Archived December 31, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, 04-06-15

- "U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services". Archived from the original on July 20, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- "Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act". Cms.hhs.gov. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- Seymour, J.A. Health Care Lie: '47 Million Uninsured Americans'. Michael Moore, politicians and the media use inflated numbers of those without health insurance to promote universal coverage. Archived September 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Business and Media Institute, July 18, 2007.

- "How Many People Lack Health Insurance and For How Long?". Congressional Budget Office Report, 2003. Archived from the original on July 5, 2006. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- "The Uninsured: A Primer" (PDF). Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Himmelstein DU, Warren E, Thorne D, Woolhandler S (2005). "Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy". Health Affairs. Suppl Web Exclusives: W5–63–W5–73. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.w5.63. PMID 15689369. S2CID 73034397.

- Todd Zywicki, "An Economic Analysis of the Consumer Bankruptcy Crisis" Archived October 30, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, 99 NWU L. Rev. 1463 (2005)

- "Medical Debt Huge Bankruptcy Culprit — Study: It's Behind Six-In-Ten Personal Filings". CBS. June 5, 2009. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved June 22, 2009.

- "National Association of Free Clinics: About Us". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ Karen E. Lasser; David U. Himmelstein; Steffie Woolhandler (July 2006). "Access to Care, Health Status, and Health Disparities in the United States and Canada: Results of a Cross-National Population-Based Survey" (PDF). American Journal of Public Health. 96 (7): 1300–1307. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402. PMC 1483879. PMID 16735628. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

In multivariate analyses, US respondents (compared with Canadians) were less likely to have a regular doctor, more likely to have unmet health needs, and more likely to forgo needed medicines ... United States residents are less able to access care than are Canadians.

- Lebrun LA & Dubay LC. (2010). Access to primary and preventive care among foreign-born adults in Canada and the United States. Health Services Research, Sept 1, 2010, 1–27 (Epub).http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01163.x/abstract

- Kent Masterson Brown, "The Freedom to Spend Your Own Money on Medical Care: A Common Casualty of Universal Coverage" Archived April 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, CATO Institute Policy Analysis no. 601, October 15, 2007

- "Myth: Medicare covers all necessary health services". Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Frequently Asked Questions: Who pays for psychological treatment?". The Ontario Psychological Association. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Frequently Asked Questions: What is the difference between a psychologist and a psychiatrist?". The Ontario Psychological Association. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "HST Update" (PDF). Ontario Society of Psychotherapists. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Health Financing". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (U.S. government). Archived from the original on January 31, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- "Parity Implementation Coalition" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 22, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- "How Do Canadians Rate the Health Care System?". Health Council of Canada. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Patient wait times in America: 9 things to know". www.beckershospitalreview.com. June 9, 2017. Archived from the original on August 11, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Skinner, Rovere, Barua, Bacchus, Mark, Brett. "Critique of the Fraser Institute report on wait times". PNHP. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fuhrmans, V. Locked Out: Note to Medicaid Patients: The Doctor Won't See You; As Program Cuts Fees, MDs Drop Out; Hurdle For Expansion of Care. Archived September 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine The Wall Street Journal, July 19, 2007.

- Erin Thompson. "Wait times to see doctor are getting longer Archived June 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." USA Today. June 3, 2009.

- "AMN Physician Surveys | AMN Healthcare" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 20, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- Commonwealth Fund, Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: An International update on the comparative performance of American health care, Karen Davis et al., May 15, 2007.

- Sally Pipes, President and CEO of the Pacific Research Institute, writing in The Washington Examiner, "Canadian patients face long waits for low-tech healthcare", June 4, 2009, page 24

- Guest columnist: The truth about Canada's ailing health-care system Archived March 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, By Robert J. Cihak, Seattle Times, July 13, 2004

- Blendon RJ, Schoen C, DesRoches CM, Osborn R, Zapert K, Raleigh E (2004). "Confronting competing demands to improve quality: a five-country hospital survey". Health Affairs. 23 (3): 119–35. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.119. PMID 15160810.

- Ontario Wait Times. Archived December 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine From: health.gov.on.ca.

- "Cancer Care Ontario". Cancercare.on.ca. Archived from the original on October 26, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "Canadian and U.S. Health Services – Let's Compare the Two," Archived July 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Letters, The Wall Street Journal, July 9, 2007; Page A13

-

Tanya Talaga (September 6, 2007). "Patients suing province over wait times: Man, woman who couldn't get quick treatment travelled to U.S. to get brain tumours removed". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

Lindsay McCreith, 66, of Newmarket and Shona Holmes, 43, of Waterdown filed a joint statement of claim yesterday against the province of Ontario. Both say their health suffered because they are denied the right to access care outside of Ontario's "government-run monopolistic" health-care system. They want to be able to buy private health insurance.

- R Bobak (November 30, 2007). "Report showed questions need asking about health care". Niagara this week. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Lynn M. Shanks (September 8, 2007). "Bring on two-tier health". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Sam Solomon (September 30, 2007). "New lawsuit threatens Ontario private care ban: "Ontario Chaoulli" case seeks to catalyze healthcare reform". Vol. 4, no. 16. National Review of Medicine. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Nadeem Esmail (February 9, 2009). "'Too Old' for Hip Surgery: As we inch towards nationalized health care, important lessons from north of the border". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- "Auditor says Ontario should post wait times for every surgeon". CBC News. October 8, 2008. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Tom Blackwell (September 6, 2007). "Lawsuit challenges ban on private care: Patient Treated In U.S.; Wait list almost cost Ontario woman her eyesight". National Post. Canada. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- "Anti-medicare ad an exaggeration: experts". CBC News. July 31, 2009. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- Ian Welsh (July 21, 2009). "Americans Lives vs. Insurance Company Profits: The Real Battle in Health Care Reform". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on July 25, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ^ "World Health Organization: Core Health Indicators". Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- Woolhandler S, Campbell T, Himmelstein DU (August 2003). "Costs of health care administration in the United States and Canada". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (8): 768–75. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa022033. PMID 12930930.

- ""Costs of Health Care Administration in the United States and Canada" (2003) Steffie Woolhandler, Terry Campbell, David U. Himmelstein, The New England Journal of Medicine" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- Sheldon L. Richman. "A Free Market for Health Care." Archived August 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine From The Dangers of Socialized Medicine, edited by Jacob G. Hornberger and Richard M. Ebeling. Future of Freedom Foundation (February 1994). ISBN 0-9640447-0-6. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- ^ Brand, R. and R. Ramirez. "Hospital, Medicaid numbers tell immigration tale" Archived September 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Rocky Mountain News, August 28, 2006.

- Insuring America's Health: Principles and Recommendations Archived August 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Institute of Medicine at the National Academies, 2004-01-14. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- Health-care overhaul begins now Archived January 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Ezra Klien, Washington Post 2010-03-28

- "Health care spending to reach $160 billion this year" (Press release). Canadian Institute for Health Information. November 13, 2007. Archived from the original on August 28, 2009. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- "Growth In National Health Expenditures Projected To Remain Steady Through 2017; Health Spending Growth" (Press release). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of Public Affairs. February 26, 2008. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- "The Canadian and American Health Care Systems". Dsp-psd.communication.gc.ca. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- David, Hogberg. "The Myths of Single Payer Health Care". Free Market Cure. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

Single-payer is popular among the political left in the United States. Leftists have emitted tons of propaganda in favor of a single-payer system, much of which has fossilized into myth.

- Health Care Systems: An International Comparison. Archived May 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Strategic Policy and Research Intergovernmental Affairs, May 2001.

- "Canadian doctor total at record high". CBC.ca. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- Conover, Chris (May 28, 2013). "Are U.S. Doctors Paid Too Much?". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

Consequently, comparing average doctor pay in the U.S. (where more than 70% of doctors are specialists) to that in nations such as Canada and France (where less than half of doctors are specialists) is not very illuminating.

- "OECD Health Data 2007: Frequently Requested Data" (Excel spreadsheet). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- "Supply, Distribution and Migration of Canadian Physicians, 2005". Canadian Institute for Health Information. October 12, 2006. p. 40, fig. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

... in the past two years, the number of physicians returning from abroad has exceeded the number of physicians moving abroad.

- "Premiers propose drug plan paid for by Ottawa". CBC. August 3, 2004. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ^ Valérie Paris and Elizabeth Docteur. Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies in Canada Archived July 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine OECD Health Working Papers

- Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, et al. (2005). "Taking the pulse of health care systems: experiences of patients with health problems in six countries". Health Affairs. Suppl Web Exclusives: W5–509–25. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.w5.509. PMID 16269444.

- Valérie Paris and Elizabeth Docteur. Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies in Canada Archived July 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine OECD Health Working Papers pg. 49

- Valérie Paris and Elizabeth Docteur. Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies in Canada Archived July 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine OECD Health Working Papers pg. 52

- Morgan, Steven; Hurley, Jeremiah (March 16, 2004). "Internet pharmacy: prices on the up-and-up". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (6): 945–946. doi:10.1503/cmaj.104001. PMC 359422. PMID 15023915.

- Gross, David. "Prescription Drug Prices in Canada: What Are the Lessons for the U.S.? Archived October 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine" AARP. July 2003. Retrieved on February 3, 2008.

- "Compendium of Guidelines, Policies and Procedures. Schedule 2 – Therapeutic Class Comparison Test". Pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "Compendium of Guidelines, Policies and Procedures. Schedule 3 – International Price Comparison". Pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- Re: E-DRUG: Patent rights on Ciprofloxacin Archived May 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine From: essentialdrugs.org.

- Skinner, Brett J. (2006). "Price Controls, Patents, and Cross-Border Internet Pharmacies" (PDF). Critical Issues Bulletin. Fraser Institute. p. 6. Retrieved July 12, 2007.

"Nearly half the value of sales (47%) in generic products sold through cross-border Internet pharmacies was accounted for by drugs that were not yet genericized in the United States. Most of these drugs were likely still under active patent protection in the United States.

- Valérie Paris and Elizabeth Docteur. Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Policies in Canada Archived July 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine OECD Health Working Papers pg. 57