The conservation and restoration of papyrus material is an activity dedicated to the preservation and protection of objects of historical and personal value made from papyrus from Ancient Egypt.

Overview

Main article: PapyrusPapyrus was used in the making of writing material in ancient Egypt, where it was used from ancient times until the 10th century CE. The species of papyrus used in the creation of the writing materials is Cyperus papyrus.

Storage for papyrus materials

There are various methods to safely store papyrus collections. However, the storage conditions do not change.

Conditions

It is important to store papyri within a climate-controlled room in which the temperature and humidity are maintained at a constant level of 17–23 °C (63–73 °F) and 50–60 percent, respectively. It is also important to place a special kind of film or glass which protects the cases holding the papyri from UV lights, which could make papyri fade away if they are exposed to these lights.

Methods

There are various methods for storing papyri. The first and most common of these is to use two frames of glass and seal the edges with cloth tape. However, this method presents many risks to the object. One of these risks is this method opens the door for the object to be in contact with heat and moisture, which would also make the object's surface to stick to the glass. Another method is using the Stabiltex Sling System, which is a much safer method to store papyrus fragments. This storage method consists the use of a double-windowed mat with two sheets of Stabiltex covering the object. A third method for storing papyri, especially for oversized papyri, is placing the papyrus between two layers of plexiglass and then securing them with an aluminum frame cut to the size to support the piece.

Threats

Papyrus collections face threats to their well-being. These threats range from biological in nature to man-made.

Insects and other biological threats

Insects have been known to damage papyri. The damage takes place when the papyrus is rolled. In ancient times, a material called cedrium was used. Cedrium is a resinous extract from juniper, which stopped bookworms from attacking papyrus scrolls. Cedar oil was also used to stop bookworms in ancient times. There are also certain species of fungi which specifically attack papyri. As organic materials, papyri are also susceptible to mold.

Deterioration

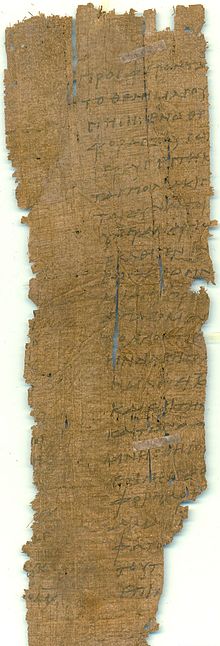

A common threat to papyrus materials is deterioration. This threat has been occurring both in ancient and modern times. In ancient times, deterioration occurred when the papyrus was used extensively, which is especially the case for medical papyri and other papyri of a similar nature. In modern times, deterioration in papyri occurs from a long process of ageing, the breaking down of the components of the papyrus as well as the conditions where the papyrus is stored/found. Another cause for deterioration among papyri is oxidation, which occurs from the use of iron gall ink, which contains iron sulphate, which has been known to damage papyri.

Salts

Salts, if accumulated on a papyrus scroll, could potentially damage it. A papyrus scroll can be contaminated with salts from the site where it was found, which is especially the case for areas with a high degree of moisture. However, salt on papyri can also occur in stable environments.

Methods of storage

Methods of storage, if done incorrectly, can also damage papyri. The traditional method in papyrus storage was to place the papyri between two sheets of glass and then seal the edges with cloth tape. This threatens the papyrus inside since it allows the object to come into direct contact with the glass, which could cause heat and moisture to come into contact with the papyrus. This could make the papyrus stick to the glass. This could also damage the ink and the surface of the papyrus when the glass is removed. A grayish material, which has been identified as a composite of sodium chloride and traces of vegetable carbohydrates, was seen around the edges of some papyri. Other storage methods which use cellulose nitrate, paper backing, drumming techniques, hinges, adhesive mounts, dry mount systems and plexiglass which presses directly on the papyrus are not considered safe methods of storage. The threats from these include introducing materials which could stain the artifact, degrading the object or placing pressure on the object. These effects are also not easily reversed.

Restoration methods

Restoring papyri has been around since ancient times. Across the centuries, more modern methods have been used. In this section, both ancient and modern techniques for restoring papyri will be examined.

Ancient methods

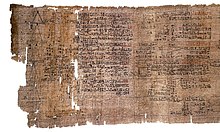

Restoring damaged papyri has been going on since ancient times. Indeed, one method that seems to have been used then was to add fresh strips of papyrus to the papyrus scroll. An example of this is seen with the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.

Modern methods for conserving and restoring papyri

Papyri can be restored using various methods in modern times. These methods differ based on the condition of the papyrus.

Preparation of a papyrus for conservation

There are several steps that need to be taken before restoring a papyrus. The first step is to first remove any remaining soil and dirt particles on the papyrus piece. After this, the next step is to document the papyrus scroll as accurately as possible. This step is especially important if the papyrus is in fragments. Then, the ink on the papyrus should be examined by pouring an eye drop of water onto the papyrus itself. This step is repeated using either ethanol or an ethanol/water mixture. Old repairs and tape can also damage a papyrus piece, so it is crucial that these are removed. One method of removing these is to first dampen the papyrus itself so the old tapes can be removed safely.

Restoring a papyrus

There are various methods which are used to restore damaged papyri, which may depend on the type of the damage on the papyrus. For example, if the ink on the papyrus has been damaged, then a very thin methyl cellulose or wheat starch paste is to be applied beneath the papyrus via a fine sable brush. If there is a mold attack, then a method which seems to work is to remove the mold via a spatula and then brush the contaminated area with a solution that is 50% water and 50% ethanol. Sometimes, a cellulose solution, which can be either Klucel or Hydroxypropyl Celluloid, is used to strengthen cell tissue and the vascular bundles. Other materials such as papyrus juice and gum arabic can be used for the same reason as the cellulose solutions. A method that is used to treat papyri is to clean repeatedly. This is achieved by first placing the papyrus on dry blotting paper, and then cleaning the papyrus by removing the dirt via a scalpel, spatula or dry tweezers. Mechanical cleaning of the papyrus can also be done, after placing the papyrus on the dry blotting paper, via the use of a bristle brush to lightly brush the papyrus. A damp papyrus must be placed under a light weight to dry. These cleaning methods can be used repeatedly until the papyrus is fully treated. After restoring the papyrus, tweezers can be used to align papyrus fragments in place. Then, the papyrus is remounted using either the Stabiltex Sling system or the Polyester Sling system.

Restoring recycled papyri

In ancient times, used papyri were often used in the creation of cartonnage coffins. The papyri used in the creation of these coffins were cut or torn and then dampened with water so they can fit into the cartonnage piece in which they were placed. Then, they were stuck together with either plaster or glue. A layer of lime gesso plaster was used on both sides of the papyrus. An image of the deceased was often painted on the front of the cartonnage. To conserve the paintings and the papyri within, any loose dirt is to be removed and the painted surface cleaned with acetone. If there are any holes in the painted gesso, then calcium carbonate is used to block these holes. The paint layer is fixed with Paraloid B-48, which contains 30 percent acetone. The layer of paint is faced with a temporary piece of cartonnage using: (a) one layer of Japanese tissue paper (about 50 grams) & Paraloid B-48/acetone emulsion (20 percent), (b) two layers of Japanese paper (about 70 grams) and a Planatol BB/water dilution (40 percent), (c) one layer of linen cloth and a Planatol BB/water dilution (40 percent) and one layer of Japanese paper (about 70 grams) and a Planatol BB/water emulsion (40 percent). The negative form of the object is then placed in either fluid polyurethane (if the object is three-dimensional) or water (60 degrees Celsius). To remove the inner layer of gesso, it is dampened in water and then removed with a brush. Then the papyrus cartonnage is removed from behind with a scalpel. To loosen the pieces of papyrus within, the cartonnage is placed in a hot water bath (90 degrees Celsius) for a few minutes. Acid is then placed in the water to help in loosening the pieces of papyrus in the gesso. After this, the papyrus pieces are de-acidified. The papyri are then separated mechanically with tweezers and scalpel. Using blotting paper, the papyri fragments are dried via sheets of blotting paper. Using Paraloid B-48 (20 percent in acetone), the painting and its gesso layer are consolidated from the back. The object is then backed by a new cartonnage support consisting of Japanese paper (70–90 grams), linen cloth and a Planatol BB/water dilution (40 percent). The negative form of the third-dimensional object is removed mechanically. The temporary-facing support is removed with tweezers and brush by using acetone. Using a brush and acetone, the painted surface is cleaned. The dry papyri are cleaned with a brush. Using a brush, tweezers and palette knives, the papyrus fragments are cleaned by sandwiching them between pieces of wet cloth or blotting paper. This will mark the final removal of any remaining gesso pieces. The papyrus fragments are dried between sheets of blotting paper while under pressure. Then the papyrus fragments are stored between glass plates.

Restoring carbonized papyri

Carbonized papyri are papyri that have been charred. There seems to be one method for restoring charred papyri. The first step of this method is to carefully separate the layers of the papyrus since they cannot be unrolled due to their condition. This separation is done with either a thin palette knife or a scraper and lifting them with tweezers. Sometimes, dampening the layers is done to speed up the process of separation. In the event that the pieces are very fragile, Japanese paper is used to loosen and lift the layers, but only if the back of the papyrus does not contain any writing. Another method is to use a dilution of water and glue to fix the layers from the back. After separating the layers one by one, the pieces in the individual layer are placed together according to the writing on the front of the papyrus. Then the layer is turned over in order to stabilize it from the back, which can be only achieved if the back of the papyrus does not have any writings. If this is the case, then the pieces cannot be consolidated, unless they are between the inscribed lines. However, this latter process is done only sometimes and with extreme care. A great method of reconstructing a layer of carbonized papyri is to use Japanese tissue paper and a sheet of glass, on which to place the layer. Then a layer of wax paper or plastic paper is placed over the whole reconstruction and then cover that with a glass plate. This step is done to ease the process of turning the papyrus layers over. Through the use of a thin paintbrush and letting the glass plate slide step-by-step, the carbonized layer is strengthened by carefully applying the diluted adhesive through the Japaneses paper from the back. To avoid air bubbles, the whole back must be glued. It is also important not to let the adhesive seep into the papyrus since this will form a reflective surface on the front of the papyrus, which will render the ink on the front of the papyrus invisible. The reinforced papyrus can be turned over by grasping the Japanese paper.

References

- Leach, Bridget; Tait, John (2001). "Papyrus". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt Vol. 3. Oxford University Press.

- Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. p. 86.

- Stanley, Ted (1994). "Papyrus Storage at Princeton University". Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Lau-Lamb, Leyla (2010). "ADVANCED PAPYROLOGICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM Guidelines for Conservation of Papyrus". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Leach, Bridget; Tait, John (2000). "Papyrus". In Nichlson, Paul T.; Shaw, Ian (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge University Press. p. 240.

- ^ Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. p. 83.

- ^ Leach, Bridget; Tait, John (2000). "Papyrus". In Nichlson, Paul T.; Shaw, Ian (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge University Press. p. 238.

- Leach, Bridget; Tait, John (2000). "Papyrus". In Nichlson, Paul T.; Shaw, Ian (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge University Press. p. 242.

- Lau-Lamb, Leyla (2010). "ADVANCED PAPYROLOGICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM Guidelines for Conservation of Papyrus". Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Stanley, Ted (1994). "Papyrus Storage at Princeton University". Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. pp. 81–82.

- Stanley, Ted (1994). "Papyrus Storage at Princeton University". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. p. 87.

- Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. pp. 88–90.

- Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. p. 91.

- ^ Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. p. 96.

- Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. pp. 96–97.

- Frösén, Jaakko (2009). "Conservation of Ancient Papyrus Materials". In Bagnell, Roger S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford University Press. p. 97.