| Chalcolithic Eneolithic, Aeneolithic, or Copper Age |

|---|

|

↑ Stone Age ↑ Neolithic |

|

By regionAfrica (2600 BC–1600 AD)

West Asia (6000–3500 BC) Europe (5500–2200 BC)

Central Asia (3700–1700 BC) South Asia (4300–1800 BC)

China (5000–2900 BC) Mesoamerica (6500–1000 BC) |

|

Related topicsMetallurgy, Wheel, Domestication of the horse |

|

↓ Bronze Age ↓ Iron Age |

Copper metallurgy in Africa encompasses the study of copper production across the continent and an understanding of how it influenced aspects of African archaeology.

Origins

Scholars previously believed that sub-Saharan Africans either did not have a period of using copper until the nineteenth century (going from the Stone Age directly into the Iron Age), or that they started smelting iron and copper at the same time. Copper smelting is thought to have been practiced in Nubia, during the early Old Kingdom c. 2686–2181 BC.

The principal evidence for this claim is an Egyptian outpost established in Buhen (near today's Sudanese-Egyptian border) around 2600 BC to smelt copper ores from Nubia. Alongside this, a crucible furnace dating to 2300–1900 BC for bronze casting has been found at the temple precinct at Kerma (in present-day northern Sudan), however the source of the tin remains unknown. Over the next millennium Nubians developed great skill in working copper and other known metals.

Discoveries in the Agadez Region of Niger evidence signs of copper metallurgy as early as 2000 BC. This date pre-dates the use of iron by a thousand years. Copper metallurgy seems to have been an indigenous invention in this area, because there is no clear evidence of influences from Northern Africa, and the Saharan wet phase was coming to an end, hindering human interactions across the Saharan region. It appeared to not be fully developed copper metallurgy, which suggests it was not from external origins. The people used native copper at first, and experimented with different furnace styles in order to smelt the ore between 2500 and 1500 BC.

Copper metallurgy has been recorded at Akjoujt in western Mauritania. The Akjoujt site is later than Agadez, dating back to around 850 BC. There is evidence of mining between 850 and 300 BC. Radiocarbon dates from the Grotte aux Chauves-souris mine shows that the extraction and smelting of malachite goes back to the early fifth century BC. A number of copper artifacts—including arrow points, spearheads, chisels, awls and plano-convex axes as well as bracelets, bead and earrings—were found at Neolithic sites in the region.

Collecting dates from Tropical Africa has been extremely difficult. No dates are available for the copper mine in pre-colonial Nigeria, and the earliest dates available south of the equator are around 345 AD at Naviundu springs near Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Kansanshi mine in Zambia and Kipushi mine in the DRC date to between the fifth and twelfth centuries. Sites further south have produced later dates, for example the Thakadu mines in Botswana date to between 1480 and 1680; other major mines in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa remain undated.

Ore sources

The mineralization of copper is restricted to a few areas in western, central and southern Africa, and some have the richest deposits of copper in the world. In the west, copper has only been found in the arid regions of the Sahel and southern Sahara. The main sources of copper are:

- Akjoujt in Mauritania

- Nioro du Sahel to Sirakoro in Northern Mali

- The Aïr Massif near Azelik and Agadez in Niger

There are not any known mines in tropical West Africa, however copper and lead workings have been in the Benue Trough in southeastern Nigeria. With the exception of a few areas near Kilembe in Uganda and Rwanda, there are no sources of copper in East Africa. The largest concentration of copper found in Africa is the Lufilian Arc. It is an eight hundred kilometer crescent shaped belt, which extends from the Copperbelt in Zambia to the southern Shaba Province in Congo.

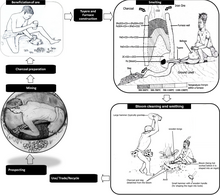

Mining and processing

Early African miners used copper oxides and carbonates rather than sulfides, because they were able to reduce oxides and carbonates to copper metal, but not sulfides. Sulfides were more complex to reduce to metal and required multiple stages. Complex deep-mining methods and special tools were not needed, because oxides were structurally weakened by decomposition processes and contained the most desirable ores, and although the techniques used seemed to be simple, Africans were very successful in extracting large quantities of high-grade ore.

The copper mines themselves were most frequently open stopes or open stopes with shafts. Shafts were rare in African copper mining. There are several ethnographic accounts of African copper mining techniques, and they all seem to be on the same technological level. Any variation depended upon different geological circumstances and capabilities of the miners.

There are more variations of copper smelting than there are of mining, and most of the observations and photos that were taken are in major copper producing areas. There is a lack of evidence of smelting in West Africa; however casting continued to be present and is well documented. The most common ore in Africa is malachite and it was used mainly with hardwood charcoal the smelting process.

Copper throughout Africa

West Africa

In sub-Saharan West Africa, there were only two known source of copper that were commercially viable: Dkra near Nioro, Mali and Takedda in Azelik, Niger. Akjoujt was a significant source of copper, but due to the lack of timber it lost its significance in early historic times. The sources for West Africa's copper came from southern Morocco, northwestern Mauritania, the Byzantine Empire and Central Europe.

The discovery of copper metallurgy in the Akjoujt region in Mauritania and the Eghazzer basin dated to the second and early first millennium BCE shook the foundation of that consensus. In all the other areas reviewed in this article, however, iron metallurgy was adopted directly by Late Stone Age mixed-farming and horticulturalist communities. A general outline of the origins of African copper metallurgy is presented by Michael S. Bisson . Native copper was exploited for one to two millennia. “The mining and smelting of copper ore appears to have arisen independently in Asia Minor, Eastern Europe, and Egypt between 5000 and 4000 BC” . He outlines a number of elements suggesting a link between the Akjoujt copper metallurgy, Western Europe Early Bronze Age, and Phoenician North Africa. First, the large proportion of utilitarian objects tends to suggest that copper technology was introduced in the area as a package, in contrast to all cases of early metallurgy development in which status objects are dominant. Second, there are striking stylistic similarities between Mauritanian, North African, and Iberic Peninsula copper artifacts. He concludes that the presence of more prosaic copper artifacts at the beginning of the Mauritanian sequence suggests that the technology may have its roots elsewhere.” The cases from the Eghazzer basin that point to the late third–early second millennium BCE age of copper smelting are still strongly debated. Egypt was suggested as the most likely initial source of the Eghazzer copper metallurgy: It is not inconceivable that communications, however indirect and periodic, between the Nile Valley and interior Sahara regions occurred over a long period and that the knowledge of working with metals (particularly copper) was along the numerous routes to the west, southwest and south. Iron technology may have been introduced along similar networks by the turn of the first millennium BC, although additional stimulus was provided by the new links to the northern coast.

In West Africa, there is a great deal of documentation about copper in trade, but the travelers who wrote these documents only visited the major centers of West African polities and there is no information on the people who lived out the polities or from the savanna and forest zones to the south, in terms of their use of copper. Arab and European trader documented that the principal goods that were in demand in West African markets were salt and copper. There has been a lack of research done in the savannah and forest regions of West Africa so the evidence of the diffusion copper there is spotty at best. Despite West Africa's rich gold resources, high status people were most often buried with copper grave goods. The only sites prior to 1500 AD to have gold were Djenné, Tedaoust, and several tumuli in Senegal.

Central and South Africa

In West Africa, copper was used as medium of exchange, symbols of status and kingship, jewelry, and ritual purposes; this was a part of Bantu tradition prior to their expansion into Central Africa. The use of copper in the Iron Age of Central Africa was produced because of indigenous or internal demand rather than those from outside, and it is thought to be a sensitive sign of political and social change.

Copper appeared to be a prestigious metal in Central and Southern Africa. In Central Africa copper has been found in places where copper is not produced, implying some sort of commerce. Also the majority of artifacts found suggest that the primary use for copper in the area was for decorative purposes. The available evidence shows that prior to fifteenth century Zimbabwean Iron Age site also placed higher value in copper than gold, though the date may have to be pushed with recent carbon dates.

It is thought that through trade with India and later Portugal Zimbabwe started to value gold as prestige metal, however it did not replace copper. Archaeological and documentary sources may skew the record in favor of nonperishable elements of culture and not give enough credit to pastoral and mixed farming activities that were needed to sustain these Iron Age populations. They do make it clear that copper was an important part of the exchange economies of Central and Southern Africa. The site of Bosutswe is evidence that copper and other precious metals were vital to trade in the area.

Tswana towns of the pre-colonial period in South Africa, such as the Tlokwa capital at Marothodi near the Pilanesberg National Park, demonstrate a continuation of native copper production into the early nineteenth century. In this period, archaeological research suggests that copper production had intensified significantly to meet growing regional demands.

East Africa

Copper is almost non-existent for most of the interior of East Africa, with a few exceptions particularly Kilwa and medieval sites in Nubia and Fostat, and there is not enough information yet to reconstruct copper on the Swahili Coast.

Symbolism

Bisson (2000) thought that because of copper's redness, luminosity and sound, it was valued by Africans. For many African cultures, the redness could be with life giving powers. Bisson (2000) also noted that the redness is a symbol of transition and it association with transition could explain why the wide use of copper in rituals in various African states. Also, its ability to reflect sunlight is suggested represent aggression and liminal boundaries between states, thus emphasizing its transformative properties. Finally, because of copper's use in bells and drums, it is thought to aid in the summoning spirits, when the instruments are played.

See also

References

- ^ Herbert 1984.

- ^ Childs & Killick 1993, p. 317–337.

- Ehret 2002.

- ^ Bisson 2000, p. 83–145.

- Herbert 1973, p. 179–194.

- Lambert, J. (1975). "Copper Metallurgy in the Akjoujt Region." African Archaeological Review, p. 1983.

- Lambert, J. (1983). "The Early Metallurgies of Mauritania." Journal of Saharan Studies, p. 1983.

- Grebenart, D. (1985). "Copper and Iron Metallurgy in the Sahara." Revue d’Archéologie Africaine, p. 198.

- Bisson, M. (2000). "The Origins of African Copper Metallurgy." African Archaeological Review.

- Bisson, M. (2000). "The Origins of African Copper Metallurgy." African Archaeological Review.

- Bisson, M. et al. (2000). "African Copper Metallurgy: Origins and Early Development." Journal of African History, Vol. 41, Issue 1, p. 88.

- Bisson, M. et al. (2000). "African Copper Metallurgy: Origins and Early Development." Journal of African History, Vol. 41, Issue 1, p. 90.

- Bisson, M. et al. (2000). "African Copper Metallurgy: Origins and Early Development." Journal of African History, Vol. 41, Issue 1, p. 90.

- Grebenart, D. (1985). "Copper and Iron Metallurgy in the Sahara." Revue d’Archéologie Africaine, p. 198.

- Grebenart, D. (1988). "The Metallurgical Evolution in North Africa." African Archaeology Review, p. 198.

- Holl,Augustin Ferdinand Charles. (1997). "The Origins of African Metallurgies." Oxford University Press, p. 2000.

- Holl, Augustin Ferdinand Charles. (2000). "The Origins of African Metallurgies." Oxford University Press, p. 2000.

- Kense, F. (1985). "Prehistoric Metallurgy in the Sahara." African Journal of Archaeology, p. 198.

- Killick, D., et al. (1988). "Early Iron and Copper Metallurgies in West Africa." Journal of African History, p. 198.

- Bisson 1975, p. 276–292.

- Denbow, James; et al. (2008-02-01). "Archaeological excavations at Bosutswe, Botswana: cultural chronology, paleo-ecology and economy". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (2): 459–480. Bibcode:2008JArSc..35..459D. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.04.011. ISSN 0305-4403.

- Anderson 2009.

Bibliography

- Anderson M (2009). Marothodi: The Historical Archaeology of an African Capital. Atikkam Media.

- Bisson M (1975). "Copper currency in central Africa: the archaeological evidence". World Archaeology. 6 (3): 276–292. doi:10.1080/00438243.1975.9979608.

- Bisson M, et al. (2000). "Precolonial copper metallurgy: sociopolitical context". Ancient Africa Metallurgy: The Socio-cultural Context. Altamira Press. pp. 83–145.

- Childs T, Killick D (1993). "Indigenous African metallurgy: nature and culture". Annual Review of Anthropology. 22: 317–337. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.22.100193.001533.

- Ehret C (2002). The Civilizations of Africa: A history to 1800 Charlottesville. University Press of Virginia.

- Herbert E (1973). "Aspects of the use of copper in pre-colonial West Africa". Journal of African History. 14 (2): 179–194. doi:10.1017/S0021853700012500.

- Herbert E (1984). Red Gold of Africa: Copper in Pre-colonial History and Culture Madison. University of Wisconsin Press.