| Music of Cuba | ||||

| General topics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related articles | ||||

| Genres | ||||

|

||||

| Specific forms | ||||

|

||||

| Media and performance | ||||

|

||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||

|

||||

| Regional music | ||||

|

||||

Coros de clave were popular choral groups that emerged at the end of the 19th century in Havana and other Cuban cities. Their style was influenced by the orfeones which grew popular in northern Spain in the mid-19th century, and their popularization in the island was linked to the emancipation of African slaves in 1886. The common instrumentation of the coros featured a viola (a string-less banjo used as a percussion instrument), claves, guitar, harp and jug bass.

History

Background

During the 19th century, the Cuban government only allowed black people, slaves or free, to cultivate their cultural traditions within the boundaries of certain mutual aid societies, which were founded during the 16th century. According to David H. Brown, those societies, called cabildos, "provided in times of sickness and death, held masses for deceased members, collected funds to buy nation-brethren out of slavery, held regular dances and diversions on Sundays and feast days, and sponsored religious masses, processions and dancing carnival groups (now called comparsas) around the annual cycle of Catholic festival days."

At the cabildos in the town of Trinidad some choral groups existed since mid-19th century that performed the so-called tonadas trinitarias. There are some references that by 1860, the tonadas trinitarias were interpreted during the local festivities by choirs from different neighborhoods, which used to gather together to compete while they paraded through the streets. Also within the cabildos of certain neighborhoods from Havana, Matanzas, Sancti Spíritus and Trinidad, some choral groups were founded during the 19th century that organized competitive activities, and in some occasions were visited by local authorities and neighbors that gave them money and presents. Those choral societies usually were named after their neighborhoods, and in some occasions they counted with one hundred or more members. Most probable of their chanting aimed to distract local authorities from investigating the real purpose of their gatherings, which was to celebrate ritual activities related to their original African religions.

Development

The origin and development of the coros de clave is linked not only to the local cabildos, but also to the traditions imported by immigrants from northern Spain, in particular the similarly named coros de Clavé (after Catalan composer Josep Anselm Clavé). Starting in 1845, Clavé established orfeones (French-style choirs) made up of working-class people in Barcelona. Similar choral traditions spread throughout the north of Spain, including Galicia, where the movement was called coralismo. According to some authors, including Odilio Urfé and Ned Sublette, upon introduction in Cuba, the coros de Clavé lost their accent, becoming coros de clave.

The coros de clave became popular in Cuba between the 1880s and the 1910s. They comprised as many as 150 men and women who sang in 6/8 time with European harmonies and instruments. Songs began with a female solo singer followed by call-and-response choral singing. As many as 60 coros de clave might have existed by 1902, some of which denied any African influence on their music. Examples of popular coros de clave include El Arpa de Oro, La Juventud, La Generación and Flor del Día.

From the coros the clave evolved the coros de guaguancó, which comprised mostly men, had a 2/4 time, and incorporated drums. Famous coros de guaguancó include El Timbre de Oro, Los Roncos (both featuring Ignacio Piñeiro, the latter as director), and Paso Franco. Some scholars such as Argeliers León nonetheless argue that the coros de clave and coros de guaguacó evolved independently of each other. The coros de guaguancó, which were considerably more africanized, gave rise some of the first authentic rumba groups, particularly guaguancó groups. Nonetheless, guaguancó also had its roots in another rumba style known as yambú, which itself derived from the Bantu yuka genre. Some rumba groups such as Clave y Guaguancó and Grupo Afrocuba de Matanzas carried part of the coros de guaguancó repertoire into the late 20th century.

Musical characteristics

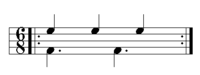

The coros de clave share their name with the percussion instrument used as accompaniment, the Cuban claves, which execute the main rhythmic pattern, the vertical hemiola (also characteristic of the contradanza). The vertical hemiola constitutes the most essential element of the sesquiáltera rhythm, and consists in the practice of superimposing a binary rhythmic pulse over a ternary one, as follows:

The accompaniment of the choirs frequently included a guitar and the percussion was executed over the sound box of an American banjo from which the strings were removed, due to the fact that African drums performance was strictly forbidden in Cuban cities.

Usually a soloist started a song by singing a nonlexical melody and also improvised variations of the themes sung by the choir. A participant called "censor" was dedicated to supervise the language utilized in the songs.

Clave genre

The musical style of the coros de clave, and particularly its rhythm, gave rise to a popular song genre called clave, which most probably served as the original prototype for the creation of the criolla genre. Both genres, the clave and the criolla, became very popular within the Cuban vernacular theater repertoire.

See also

References

- ^ Bodenheimer, Rebecca (2014). "Coros de clave". In Shepherd, John; Horn, David (eds.). Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume 9. London, UK: Bloomsbury. pp. 223–225. ISBN 9781441132253.

- Moore, Robin (2006). Music and Revolution: Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. p. 311. ISBN 9780520247109.

- Brown, David H (2003). Santería Enthroned. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL. p. 34.

- Frías, Johnny: Notes to the CD Tonadas Trinitarias. Conjunto Folklórico de Trinidad. EGREM LD – 4383.

- Veitia, Héctor (1974). Tonadas Trinitarias.

- ^ Sublette, Ned (2004). "Rumba". Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press. pp. 257–272.

- Urfé, Odilio (1977). "Presencia africana en la música y la danza cubanas". In Moreno Fraginals, Manuel (ed.). África en América Latina (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Siglo XXI. p. 231. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Betancur Álvarez, Fabio (1999). Sin clave y bongó no hay son: música afrocubana y confluencias musicales de Colombia y Cuba (in Spanish). Medellín, Colombia: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia. p. 83.

- ^ Moore, Robin (1997). Nationalizing Blackness: Afrocubansimo and artistic Revolution in Havana, 1920-1940. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780822971856.

- Díaz Ayala, Cristóbal: Discografía de la Música Cubana. Editorial Corripio C. por A., República Dominicana, 1994, p. 122.

- Roy, Maya (2003). Músicas cubanas (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Akal. pp. 68–70. ISBN 9788446012344.

- Sublette, Ned: Cuba and its music. Chicago Review Press, Inc., 2004, p. 264.

- Orovio, Helio: Cuban music from A to Z. Tumi Music Ltd. Bath, U.K., 2004, p. 54.

- Orovio, Helio: Cuban music from A to Z. Tumi Music Ltd. Bath, U.K., 2004, p. 60.

External links

- Coro de Clave – Marcha la Moralidad: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i8pjq4uGb9Q

- Clave – Como brillan las estrellas: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AZ_2SuwWAs4