In economics, comparative statics is the comparison of two different economic outcomes, before and after a change in some underlying exogenous parameter.

As a type of static analysis it compares two different equilibrium states, after the process of adjustment (if any). It does not study the motion towards equilibrium, nor the process of the change itself.

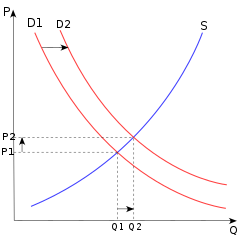

Comparative statics is commonly used to study changes in supply and demand when analyzing a single market, and to study changes in monetary or fiscal policy when analyzing the whole economy. Comparative statics is a tool of analysis in microeconomics (including general equilibrium analysis) and macroeconomics. Comparative statics was formalized by John R. Hicks (1939) and Paul A. Samuelson (1947) (Kehoe, 1987, p. 517) but was presented graphically from at least the 1870s.

For models of stable equilibrium rates of change, such as the neoclassical growth model, comparative dynamics is the counterpart of comparative statics (Eatwell, 1987).

Linear approximation

Comparative statics results are usually derived by using the implicit function theorem to calculate a linear approximation to the system of equations that defines the equilibrium, under the assumption that the equilibrium is stable. That is, if we consider a sufficiently small change in some exogenous parameter, we can calculate how each endogenous variable changes using only the first derivatives of the terms that appear in the equilibrium equations.

For example, suppose the equilibrium value of some endogenous variable is determined by the following equation:

where is an exogenous parameter. Then, to a first-order approximation, the change in caused by a small change in must satisfy:

Here and represent the changes in and , respectively, while and are the partial derivatives of with respect to and (evaluated at the initial values of and ), respectively. Equivalently, we can write the change in as:

Dividing through the last equation by da gives the comparative static derivative of x with respect to a, also called the multiplier of a on x:

Many equations and unknowns

All the equations above remain true in the case of a system of equations in unknowns. In other words, suppose represents a system of equations involving the vector of unknowns , and the vector of given parameters . If we make a sufficiently small change in the parameters, then the resulting changes in the endogenous variables can be approximated arbitrarily well by . In this case, represents the × matrix of partial derivatives of the functions with respect to the variables , and represents the × matrix of partial derivatives of the functions with respect to the parameters . (The derivatives in and are evaluated at the initial values of and .) Note that if one wants just the comparative static effect of one exogenous variable on one endogenous variable, Cramer's Rule can be used on the totally differentiated system of equations .

Stability

The assumption that the equilibrium is stable matters for two reasons. First, if the equilibrium were unstable, a small parameter change might cause a large jump in the value of , invalidating the use of a linear approximation. Moreover, Paul A. Samuelson's correspondence principle states that stability of equilibrium has qualitative implications about the comparative static effects. In other words, knowing that the equilibrium is stable may help us predict whether each of the coefficients in the vector is positive or negative. Specifically, one of the n necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for stability is that the determinant of the n×n matrix B have a particular sign; since this determinant appears as the denominator in the expression for , the sign of the determinant influences the signs of all the elements of the vector of comparative static effects.

An example of the role of the stability assumption

Suppose that the quantities demanded and supplied of a product are determined by the following equations:

where is the quantity demanded, is the quantity supplied, P is the price, a and c are intercept parameters determined by exogenous influences on demand and supply respectively, b < 0 is the reciprocal of the slope of the demand curve, and g is the reciprocal of the slope of the supply curve; g > 0 if the supply curve is upward sloped, g = 0 if the supply curve is vertical, and g < 0 if the supply curve is backward-bending. If we equate quantity supplied with quantity demanded to find the equilibrium price , we find that

This means that the equilibrium price depends positively on the demand intercept if g – b > 0, but depends negatively on it if g – b < 0. Which of these possibilities is relevant? In fact, starting from an initial static equilibrium and then changing a, the new equilibrium is relevant only if the market actually goes to that new equilibrium. Suppose that price adjustments in the market occur according to

where > 0 is the speed of adjustment parameter and is the time derivative of the price — that is, it denotes how fast and in what direction the price changes. By stability theory, P will converge to its equilibrium value if and only if the derivative is negative. This derivative is given by

This is negative if and only if g – b > 0, in which case the demand intercept parameter a positively influences the price. So we can say that while the direction of effect of the demand intercept on the equilibrium price is ambiguous when all we know is that the reciprocal of the supply curve's slope, g, is negative, in the only relevant case (in which the price actually goes to its new equilibrium value) an increase in the demand intercept increases the price. Note that this case, with g – b > 0, is the case in which the supply curve, if negatively sloped, is steeper than the demand curve.

Without constraints

Suppose is a smooth and strictly concave objective function where x is a vector of n endogenous variables and q is a vector of m exogenous parameters. Consider the unconstrained optimization problem . Let , the n by n matrix of first partial derivatives of with respect to its first n arguments x1,...,xn. The maximizer is defined by the n×1 first order condition .

Comparative statics asks how this maximizer changes in response to changes in the m parameters. The aim is to find .

The strict concavity of the objective function implies that the Jacobian of f, which is exactly the matrix of second partial derivatives of p with respect to the endogenous variables, is nonsingular (has an inverse). By the implicit function theorem, then, may be viewed locally as a continuously differentiable function, and the local response of to small changes in q is given by

Applying the chain rule and first order condition,

(See Envelope theorem).

Application for profit maximization

Suppose a firm produces n goods in quantities . The firm's profit is a function p of and of m exogenous parameters which may represent, for instance, various tax rates. Provided the profit function satisfies the smoothness and concavity requirements, the comparative statics method above describes the changes in the firm's profit due to small changes in the tax rates.

With constraints

A generalization of the above method allows the optimization problem to include a set of constraints. This leads to the general envelope theorem. Applications include determining changes in Marshallian demand in response to changes in price or wage.

Limitations and extensions

One limitation of comparative statics using the implicit function theorem is that results are valid only in a (potentially very small) neighborhood of the optimum—that is, only for very small changes in the exogenous variables. Another limitation is the potentially overly restrictive nature of the assumptions conventionally used to justify comparative statics procedures. For example, John Nachbar discovered in one of his case studies that using comparative statics in general equilibrium analysis works best with very small, individual level of data rather than at an aggregate level.

Paul Milgrom and Chris Shannon pointed out in 1994 that the assumptions conventionally used to justify the use of comparative statics on optimization problems are not actually necessary—specifically, the assumptions of convexity of preferred sets or constraint sets, smoothness of their boundaries, first and second derivative conditions, and linearity of budget sets or objective functions. In fact, sometimes a problem meeting these conditions can be monotonically transformed to give a problem with identical comparative statics but violating some or all of these conditions; hence these conditions are not necessary to justify the comparative statics. Stemming from the article by Milgrom and Shannon as well as the results obtained by Veinott and Topkis an important strand of operational research was developed called monotone comparative statics. In particular, this theory concentrates on the comparative statics analysis using only conditions that are independent of order-preserving transformations. The method uses lattice theory and introduces the notions of quasi-supermodularity and the single-crossing condition. The wide application of monotone comparative statics to economics includes production theory, consumer theory, game theory with complete and incomplete information, auction theory, and others.

See also

Notes

- (Mas-Colell, Whinston, and Green, 1995, p. 24; Silberberg and Suen, 2000)

- Fleeming Jenkin (1870), "The Graphical Representation of the Laws of Supply and Demand, and their Application to Labour," in Alexander Grant, Recess Studies and (1872), "On the principles which regulate the incidence of taxes," Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1871-2, pp. 618-30., also in Papers, Literary, Scientific, &c, v. 2 (1887), ed. S.C. Colvin and J.A. Ewing via scroll to chapter links.

- Samuelson, Paul, "The stability of equilibrium: Comparative statics and dynamics", Econometrica 9, April 1941, 97-120: introduces the concept of the correspondence principle.

- Samuelson, Paul, "The stability of equilibrium: Linear and non-linear systems", Econometrica 10(1), January 1942, 1-25: coins the term "correspondence principle".

- Baumol, William J., Economic Dynamics, Macmillan Co., 3rd edition, 1970.

- "U-M Weblogin". weblogin.umich.edu. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_322-2. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- Milgrom, Paul, and Shannon, Chris. "Monotone Comparative Statics" (1994). Econometrica, Vol. 62 Issue 1, pp. 157-180.

- Veinott (1992): Lattice programming: qualitative optimization and equilibria. MS Stanford.

- See: Topkis, D. M. (1979): “Equilibrium Points in Nonzero-Sum n-Person Submodular Games,” SIAM Journal of Control and Optimization, 17, 773–787; as well as Topkis, D. M. (1998): Supermodularity and Complementarity, Frontiers of economic research, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691032443.

- See: Topkis, D. M. (1998): Supermodularity and Complementarity, Frontiers of economic research, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691032443; and Vives, X. (2001): Oligopoly Pricing: Old Ideas and New Tools. MIT Press, ISBN 9780262720403.

References

- John Eatwell et al., ed. (1987). "Comparative dynamics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 1, p. 517.

- John R. Hicks (1939). Value and Capital.

- Timothy J. Kehoe, 1987. "Comparative statics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 1, pp. 517–20.

- Andreu Mas-Colell, Michael D. Whinston, and Jerry R. Green, 1995. Microeconomic Theory.

- Paul A. Samuelson (1947). Foundations of Economic Analysis.

- Eugene Silberberg and Wing Suen, 2000. The Structure of Economics: A Mathematical Analysis, 3rd edition.

External links

- San Jose State University Economics Department - Comparative Statics Analysis

- AmosWeb Glossary

- IFCI Risk Institute Glossary (from the American Stock Exchange glossary)

is determined by the following equation:

is determined by the following equation:

is an exogenous parameter. Then, to a first-order approximation, the change in

is an exogenous parameter. Then, to a first-order approximation, the change in

and

and  represent the changes in

represent the changes in  and

and  are the partial derivatives of

are the partial derivatives of  with respect to

with respect to

equations in

equations in  represents a system of

represents a system of  given parameters

given parameters  . In this case,

. In this case,  .

.

is positive or negative. Specifically, one of the n necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for stability is that the

is positive or negative. Specifically, one of the n necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for stability is that the  , the sign of the determinant influences the signs of all the elements of the vector

, the sign of the determinant influences the signs of all the elements of the vector  of comparative static effects.

of comparative static effects.

is the quantity demanded,

is the quantity demanded,  is the quantity supplied, P is the price, a and c are intercept parameters determined by exogenous influences on demand and supply respectively, b < 0 is the reciprocal of the slope of the

is the quantity supplied, P is the price, a and c are intercept parameters determined by exogenous influences on demand and supply respectively, b < 0 is the reciprocal of the slope of the  , we find that

, we find that

> 0 is the speed of adjustment parameter and

> 0 is the speed of adjustment parameter and  is the

is the  is negative. This derivative is given by

is negative. This derivative is given by

is a smooth and strictly concave objective function where x is a vector of n endogenous variables and q is a vector of m exogenous parameters. Consider the unconstrained optimization problem

is a smooth and strictly concave objective function where x is a vector of n endogenous variables and q is a vector of m exogenous parameters. Consider the unconstrained optimization problem  .

Let

.

Let  , the n by n matrix of first partial derivatives of

, the n by n matrix of first partial derivatives of  is defined by the n×1 first order condition

is defined by the n×1 first order condition  .

.

.

.

. The firm's profit is a function p of

. The firm's profit is a function p of  which may represent, for instance, various tax rates. Provided the profit function satisfies the smoothness and concavity requirements, the comparative statics method above describes the changes in the firm's profit due to small changes in the tax rates.

which may represent, for instance, various tax rates. Provided the profit function satisfies the smoothness and concavity requirements, the comparative statics method above describes the changes in the firm's profit due to small changes in the tax rates.