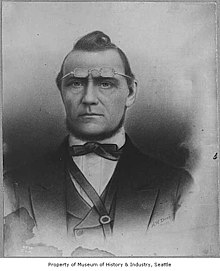

| Doc Maynard | |

|---|---|

Doc Maynard, circa 1868 Doc Maynard, circa 1868 | |

| Born | David Swinson Maynard (1808-03-22)March 22, 1808 Castleton, Vermont, United States |

| Died | March 13, 1873(1873-03-13) (aged 64) Seattle, Washington Territory, United States |

| Occupation(s) | Pioneer, doctor, businessman |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 2 |

David Swinson "Doc" Maynard (March 22, 1808 – March 13, 1873) was an American doctor and businessman. He was one of Seattle's primary founders. Maynard was Seattle's first doctor, merchant prince, second lawyer, Sub-Indian Agent, Justice of the Peace, and architect of the Point Elliott Treaty of 1855.

Early life

Maynard was born to a family of means near Castleton, Vermont. At the age of 17 he was accepted into Castleton Medical School (which at the time was associated with Middlebury College). He was top in his class and apprenticed to Dr. Theodore Woodward (not to be confused with Dr. Theodore E. Woodward).

In 1828 he married Lydia A. Rickey; they had a daughter, Frances, in 1830 and a son, Henry, in 1834. According to court papers, he discovered in 1841 that she was unfaithful to him but remained with her until 1850.

In 1832, the Maynards moved to Cleveland, Ohio, at the time a town of 500. He made and lost small fortunes in business and political ventures including railroading and a medical school that collapsed in the Panic of 1837. Maynard left Cleveland in 1850, either promising to send for his family when he was settled elsewhere, or giving Lydia the chance to file for divorce on the grounds of desertion; either way, she never actually completed the divorce.

Maynard took the railroad to St. Louis, and from there set out for California. He circulated among several wagon trains fighting cholera, which he had learned about during the 1849 epidemic in Cleveland. When the leader of one small wagon train heading for Oregon Territory died, he assumed leadership and thus ended up on Puget Sound. He and widow Catherine Troutman Broshears (June 19, 1816 - Oct 20, 1906) fell in love during their journey; however her brother, Mike Simmons, refused them permission to marry, perhaps on the grounds that Maynard was still married.

Early ventures in Seattle

Maynard joined in the logging activity at New York-Alki (later Seattle), near the mouth of the Duwamish River on Puget Sound. Instead of selling his wood to shippers at $4 a cord, he leased a vessel from Captain Felker, using the wood itself as security, and sold the load in San Francisco at ten times the price. With that money, he bought the fixings for a general store and briefly set up in competition to the only other such store on Puget Sound, which was in Olympia and owned by Catherine's brother. Mike soon agreed to his sister marrying Maynard, apparently on condition that they move the store to Duwamps and do something about that prior marriage.

In April 1852, Maynard claimed, as a married man, a tract of land of 640 acres in what is now Seattle's Pioneer Square neighborhood, and hired Indians to help him build a combination cabin and store. According to historian Bill Speidel, the land he preferred was the undeveloped southern part of Carson Boren's claim, but while Boren was out of town, Arthur Denny shifted Carson's claim north to make room for Maynard. Maynard's building became a hub of activity when Maynard became King County's first Justice of the Peace.

Maynard laid out streets in his claim according to the cardinal directions (north/south) but Boren and Denny insisted on orienting the streets according to their stretch of shoreline. Seattle's downtown still shows awkward bends and jogs where the plats meet, but the rest of King County follows Maynard's original design. In reference to the disagreement Arthur Denny would go on to comment that "Maynard was king of all he surveyed, and some of what Boren and I surveyed as well." In a study conducted by the City of Seattle in the 1930s it was determined that Denny has platted his streets in violation of donation land claim law under which the original land claims were filed.

Doc Maynard's character and approach to city-building differed from that of his contemporaries William Bell, Arthur Denny, David Denny, Henry Yesler, and Carson Boren. In part, this may have been because he was much older and had already participated in the development of one city. He drank liquor (while the Denny Party were mostly teetotalers) and, with his friend Captain Felker, found someone to start a good brothel in Seattle — the infamous Mother Damnable — believing that vice was essential to the economic success of a frontier town of that time.

Maynard's political skills helped defuse difficult situations with the Indian tribes, in particular between the Duwamish and the more powerful Snohomish, led by Chief Patkanim. As part of his diplomacy, Maynard worked to rename the settlement after the Duwamish's leader, Chief Sealth (or "Seattle") in exchange for an annual payment to Sealth (local legend has it that the tribes believed having one's name spoken after their death would disturb the named one in the afterlife; hence the payoff to Sealth to make up for that in advance). This friendly relationship paid off during the Battle of Seattle (1856) when both Sealth and Patkanim kept their fighters out of the battle.

Maynard was one of 44 delegates to attend the Monticello Convention in 1852. His political skills were helpful in drafting a Memorial to Congress persuading the legislature to divide the Oregon Territory and create a separate Washington Territory, north of the Columbia River; in return, the legislature passed an unusual bill granting Maynard a divorce. He married Catherine on January 15, 1853.

Maynard developed many clever ways to improve his property and his city. For example, he obtained the right to host the post office at his store; as a result, everyone had to come to his establishment to get their mail. He sold a lot cheaply to blacksmith Lewis Wyckoff; people needing smithing therefore came to Seattle instead of its rival Port Madison. Perhaps his greatest coup was persuading Henry Yesler to set up a steam sawmill on land sliced from the north part of Maynard's claim and the south part of Boren's. This sawmill helped establish Seattle's economic ascendancy.

When the only lawyer in Seattle died in a canoeing accident, Maynard studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1856. In 1857, Doc Maynard traded his "downtown" acreage for Charles C. Terry's farm in West Seattle, but this new enterprise did not prosper; he and Catherine then opened a two-room hospital in what is now Pioneer Square. This enterprise failed because a number of settlers refused to use the hospital after the Maynards insisted on serving both whites and Indians.

Later life

Doc Maynard was known as a friend to the Indians; when Washington became a territory in 1853 Doc Maynard was appointed as the man in charge of Indian relations. During the Seattle Indian war Doc Maynard protected the natives and ensured that they did not starve.

Although Maynard was originally one of the city's largest landholders and strongest boosters, he is considered not to have prospered as well as his contemporaries. Among the reasons given for this are that his friendly relations with Chief Seattle and other natives made him suspect to his fellow settlers. The surviving city fathers minimized his role in their reminiscences in response to Maynard's autocratic rule of early Seattle. At any rate, he died in a mansion furnished with every comfort. It is important to note that Maynard's stated purpose was not to get rich but rather to build the greatest city in the world.

Near the end of his life, Maynard's first wife Lydia sold any rights she may have had in Maynard's property to a person who promptly sued Maynard for Lydia's share of Maynard's property in Seattle (claiming that they had never been divorced; while he was still married when he built his fortune, the common law is not entirely clear as to her claim). Lydia arrived penniless in Seattle to testify on Maynard's behalf; he and Catherine let her stay in their mansion on friendly terms. As Bill Speidel has written, Maynard was seen strolling around town, the only man in Seattle with a wife on either arm.

The ultimate result of this land dispute is that the east half of Maynard's claim reverted to public land, as neither of his wives had satisfied their requirements for their share; the legal battle passed through several hands until it was ultimately decided against all the Maynards in the United States Supreme Court case of Maynard v. Hill.

See also

References

- Ferguson, Robert L. (1995). The Pioneers of Lake View: A Guide to Seattle's Early Settlers and Their Cemetery. Thistle Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-9621935-5-2. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Junius Rochester (November 10, 1998). "Maynard, Dr. David Swinson (1808-1873)". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- The History of the Pacific Northwest Oregon and Washington 1889: Volume I. Portland: North Pacific History Company. 1889.

- ^ "MAYNARD v. HILL, 125 U.S. 190 (1888)". United States Supreme Court. 1888. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

Further reading

- A brief biography of Doc Maynard at historylink.org.

- Bill Speidel, Doc Maynard, The Man Who Invented Seattle (Seattle: Nettle Creek Publishing Co., 1978) (ISBN 0-914890-02-6).

- Murray Morgan, Skid Road (New York, Ballantine Books, 1951, 1960, and other edition) (ISBN 0-295-95846-4 )

- Jones, Nard (1972), Seattle, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-01875-4