In propositional logic and Boolean algebra, De Morgan's laws, also known as De Morgan's theorem, are a pair of transformation rules that are both valid rules of inference. They are named after Augustus De Morgan, a 19th-century British mathematician. The rules allow the expression of conjunctions and disjunctions purely in terms of each other via negation.

The rules can be expressed in English as:

- The negation of "A and B" is the same as "not A or not B".

- The negation of "A or B" is the same as "not A and not B".

or

- The complement of the union of two sets is the same as the intersection of their complements

- The complement of the intersection of two sets is the same as the union of their complements

or

- not (A or B) = (not A) and (not B)

- not (A and B) = (not A) or (not B)

where "A or B" is an "inclusive or" meaning at least one of A or B rather than an "exclusive or" that means exactly one of A or B.

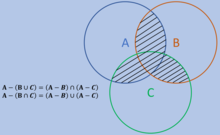

Another form of De Morgan's law is the following as seen below.

Applications of the rules include simplification of logical expressions in computer programs and digital circuit designs. De Morgan's laws are an example of a more general concept of mathematical duality.

Formal notation

The negation of conjunction rule may be written in sequent notation:

The negation of disjunction rule may be written as:

In rule form: negation of conjunction

and negation of disjunction

and expressed as truth-functional tautologies or theorems of propositional logic:

where and are propositions expressed in some formal system.

The generalized De Morgan's laws provide an equivalence for negating a conjunction or disjunction involving multiple terms.

For a set of propositions , the generalized De Morgan's Laws are as follows:

These laws generalize De Morgan's original laws for negating conjunctions and disjunctions.

Substitution form

De Morgan's laws are normally shown in the compact form above, with the negation of the output on the left and negation of the inputs on the right. A clearer form for substitution can be stated as:

This emphasizes the need to invert both the inputs and the output, as well as change the operator when doing a substitution.

Set theory

In set theory, it is often stated as "union and intersection interchange under complementation", which can be formally expressed as:

where:

- is the negation of , the overline being written above the terms to be negated,

- is the intersection operator (AND),

- is the union operator (OR).

Unions and intersections of any number of sets

The generalized form is

where I is some, possibly countably or uncountably infinite, indexing set.

In set notation, De Morgan's laws can be remembered using the mnemonic "break the line, change the sign".

Boolean algebra

In Boolean algebra, similarly, this law which can be formally expressed as:

where:

- is the negation of , the overline being written above the terms to be negated,

- is the logical conjunction operator (AND),

- is the logical disjunction operator (OR).

which can be generalized to

Engineering

In electrical and computer engineering, De Morgan's laws are commonly written as:

and

where:

- is the logical AND,

- is the logical OR,

- the overbar is the logical NOT of what is underneath the overbar.

Text searching

De Morgan's laws commonly apply to text searching using Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT. Consider a set of documents containing the words "cats" and "dogs". De Morgan's laws hold that these two searches will return the same set of documents:

- Search A: NOT (cats OR dogs)

- Search B: (NOT cats) AND (NOT dogs)

The corpus of documents containing "cats" or "dogs" can be represented by four documents:

- Document 1: Contains only the word "cats".

- Document 2: Contains only "dogs".

- Document 3: Contains both "cats" and "dogs".

- Document 4: Contains neither "cats" nor "dogs".

To evaluate Search A, clearly the search "(cats OR dogs)" will hit on Documents 1, 2, and 3. So the negation of that search (which is Search A) will hit everything else, which is Document 4.

Evaluating Search B, the search "(NOT cats)" will hit on documents that do not contain "cats", which is Documents 2 and 4. Similarly the search "(NOT dogs)" will hit on Documents 1 and 4. Applying the AND operator to these two searches (which is Search B) will hit on the documents that are common to these two searches, which is Document 4.

A similar evaluation can be applied to show that the following two searches will both return Documents 1, 2, and 4:

- Search C: NOT (cats AND dogs),

- Search D: (NOT cats) OR (NOT dogs).

History

The laws are named after Augustus De Morgan (1806–1871), who introduced a formal version of the laws to classical propositional logic. De Morgan's formulation was influenced by the algebraization of logic undertaken by George Boole, which later cemented De Morgan's claim to the find. Nevertheless, a similar observation was made by Aristotle, and was known to Greek and Medieval logicians. For example, in the 14th century, William of Ockham wrote down the words that would result by reading the laws out. Jean Buridan, in his Summulae de Dialectica, also describes rules of conversion that follow the lines of De Morgan's laws. Still, De Morgan is given credit for stating the laws in the terms of modern formal logic, and incorporating them into the language of logic. De Morgan's laws can be proved easily, and may even seem trivial. Nonetheless, these laws are helpful in making valid inferences in proofs and deductive arguments.

Proof for Boolean algebra

De Morgan's theorem may be applied to the negation of a disjunction or the negation of a conjunction in all or part of a formula.

Negation of a disjunction

In the case of its application to a disjunction, consider the following claim: "it is false that either of A or B is true", which is written as:

In that it has been established that neither A nor B is true, then it must follow that both A is not true and B is not true, which may be written directly as:

If either A or B were true, then the disjunction of A and B would be true, making its negation false. Presented in English, this follows the logic that "since two things are both false, it is also false that either of them is true".

Working in the opposite direction, the second expression asserts that A is false and B is false (or equivalently that "not A" and "not B" are true). Knowing this, a disjunction of A and B must be false also. The negation of said disjunction must thus be true, and the result is identical to the first claim.

Negation of a conjunction

The application of De Morgan's theorem to conjunction is very similar to its application to a disjunction both in form and rationale. Consider the following claim: "it is false that A and B are both true", which is written as:

In order for this claim to be true, either or both of A or B must be false, for if they both were true, then the conjunction of A and B would be true, making its negation false. Thus, one (at least) or more of A and B must be false (or equivalently, one or more of "not A" and "not B" must be true). This may be written directly as,

Presented in English, this follows the logic that "since it is false that two things are both true, at least one of them must be false".

Working in the opposite direction again, the second expression asserts that at least one of "not A" and "not B" must be true, or equivalently that at least one of A and B must be false. Since at least one of them must be false, then their conjunction would likewise be false. Negating said conjunction thus results in a true expression, and this expression is identical to the first claim.

Proof for set theory

Here we use to denote the complement of A, as above in § Set theory and Boolean algebra. The proof that is completed in 2 steps by proving both and .

Part 1

Let . Then, .

Because , it must be the case that or .

If , then , so .

Similarly, if , then , so .

Thus, ;

that is, .

Part 2

To prove the reverse direction, let , and for contradiction assume .

Under that assumption, it must be the case that ,

so it follows that and , and thus and .

However, that means , in contradiction to the hypothesis that ,

therefore, the assumption must not be the case, meaning that .

Hence, ,

that is, .

Conclusion

If and , then ; this concludes the proof of De Morgan's law.

The other De Morgan's law, , is proven similarly.

Generalising De Morgan duality

In extensions of classical propositional logic, the duality still holds (that is, to any logical operator one can always find its dual), since in the presence of the identities governing negation, one may always introduce an operator that is the De Morgan dual of another. This leads to an important property of logics based on classical logic, namely the existence of negation normal forms: any formula is equivalent to another formula where negations only occur applied to the non-logical atoms of the formula. The existence of negation normal forms drives many applications, for example in digital circuit design, where it is used to manipulate the types of logic gates, and in formal logic, where it is needed to find the conjunctive normal form and disjunctive normal form of a formula. Computer programmers use them to simplify or properly negate complicated logical conditions. They are also often useful in computations in elementary probability theory.

Let one define the dual of any propositional operator P(p, q, ...) depending on elementary propositions p, q, ... to be the operator defined by

Extension to predicate and modal logic

This duality can be generalised to quantifiers, so for example the universal quantifier and existential quantifier are duals:

To relate these quantifier dualities to the De Morgan laws, set up a model with some small number of elements in its domain D, such as

- D = {a, b, c}.

Then

and

But, using De Morgan's laws,

and

verifying the quantifier dualities in the model.

Then, the quantifier dualities can be extended further to modal logic, relating the box ("necessarily") and diamond ("possibly") operators:

In its application to the alethic modalities of possibility and necessity, Aristotle observed this case, and in the case of normal modal logic, the relationship of these modal operators to the quantification can be understood by setting up models using Kripke semantics.

In intuitionistic logic

Three out of the four implications of de Morgan's laws hold in intuitionistic logic. Specifically, we have

and

The converse of the last implication does not hold in pure intuitionistic logic. That is, the failure of the joint proposition cannot necessarily be resolved to the failure of either of the two conjuncts. For example, from knowing it not to be the case that both Alice and Bob showed up to their date, it does not follow who did not show up. The latter principle is equivalent to the principle of the weak excluded middle ,

This weak form can be used as a foundation for an intermediate logic. For a refined version of the failing law concerning existential statements, see the lesser limited principle of omniscience , which however is different from .

The validity of the other three De Morgan's laws remains true if negation is replaced by implication for some arbitrary constant predicate C, meaning that the above laws are still true in minimal logic.

Similarly to the above, the quantifier laws:

and

are tautologies even in minimal logic with negation replaced with implying a fixed , while the converse of the last law does not have to be true in general.

Further, one still has

but their inversion implies excluded middle, .

In computer engineering

- De Morgan's laws are widely used in computer engineering and digital logic for the purpose of simplifying circuit designs.

- In modern programming languages, due to the optimisation of compilers and interpreters, the performance differences between these options are negligible or completely absent.

See also

- Conjunction/disjunction duality

- Homogeneity (linguistics)

- Isomorphism

- List of Boolean algebra topics

- List of set identities and relations

- Positive logic

- De_Morgan_algebra

References

- Copi, Irving M.; Cohen, Carl; McMahon, Kenneth (2016). Introduction to Logic. doi:10.4324/9781315510897. ISBN 9781315510880.

- Hurley, Patrick J. (2015), A Concise Introduction to Logic (12th ed.), Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-1-285-19654-1

- Moore, Brooke Noel (2012). Critical thinking. Richard Parker (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-803828-0. OCLC 689858599.

- DeMorgan's [sic] Theorem

- Boolean Algebra by R. L. Goodstein. ISBN 0-486-45894-6

- 2000 Solved Problems in Digital Electronics by S. P. Bali

- "DeMorgan's Theorems". Middle Tennessee State University. Archived from the original on 2008-03-23.

- Bocheński's History of Formal Logic

- William of Ockham, Summa Logicae, part II, sections 32 and 33.

- Jean Buridan, Summula de Dialectica. Trans. Gyula Klima. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. See especially Treatise 1, Chapter 7, Section 5. ISBN 0-300-08425-0

- Robert H. Orr. "Augustus De Morgan (1806–1871)". Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis. Archived from the original on 2010-07-15.

- Wirth, Niklaus (1995), Digital Circuit Design for Computer Science Students: An Introductory Textbook, Springer, p. 16, ISBN 9783540585770

External links

- "Duality principle", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001

- Weisstein, Eric W. "de Morgan's Laws". MathWorld.

- de Morgan's laws at PlanetMath.

- Duality in Logic and Language, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

| Classical logic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||

| Classical logics | |||||

| Principles | |||||

| Rules |

| ||||

| People | |||||

| Works | |||||

| Set theory | ||

|---|---|---|

| Overview |  | |

| Axioms | ||

| Operations |

| |

| ||

| Set types | ||

| Theories | ||

| ||

| Set theorists | ||

and

and  are propositions expressed in some formal system.

are propositions expressed in some formal system.

, the generalized De Morgan's Laws are as follows:

, the generalized De Morgan's Laws are as follows:

is the negation of

is the negation of  , the

, the  is the

is the  is the

is the

is the

is the  is the

is the

is the logical AND,

is the logical AND, is the logical OR,

is the logical OR,

is completed in 2 steps by proving both

is completed in 2 steps by proving both  and

and  .

.

. Then,

. Then,  .

.

, it must be the case that

, it must be the case that  or

or  .

.

, so

, so  .

.

, so

, so  ;

;

.

.

,

,

and

and  , and thus

, and thus  and

and  .

.

, in contradiction to the hypothesis that

, in contradiction to the hypothesis that  ,

,

, is proven similarly.

, is proven similarly.

defined by

defined by

cannot necessarily be resolved to the failure of either of the two

cannot necessarily be resolved to the failure of either of the two  ,

,

, which however is different from

, which however is different from  .

.

is replaced by implication

is replaced by implication  for some arbitrary constant predicate C, meaning that the above laws are still true in

for some arbitrary constant predicate C, meaning that the above laws are still true in

.

.