"DLB" redirects here. For other uses, see DLB (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Lewy body dementia, an umbrella term encompassing Parkinson's disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies.

Medical condition

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Diffuse Lewy body disease, dementia due to Lewy body disease |

| |

| Microscopic image of a Lewy body (adjacent to arrowhead) in a neuron of the substantia nigra; scale bar=20 microns (0.02 mm) | |

| Specialty | Neurology, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Dementia, abnormal behavior during REM sleep, fluctuations in alertness, visual hallucinations, parkinsonism |

| Usual onset | After the age of 50, median 76 |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and biomarkers |

| Differential diagnosis | Alzheimer's, Parkinson's disease dementia, certain mental illnesses, vascular dementia |

| Medication | Donepezil, rivastigmine and memantine; melatonin |

| Prognosis | Variable; average survival 4 years from diagnosis |

| Frequency | About 0.4% of persons older than 65 |

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia characterized by changes in sleep, behavior, cognition, movement, and regulation of automatic bodily functions. Memory loss is not always an early symptom. The disease worsens over time and is usually diagnosed when cognitive impairment interferes with normal daily functioning. Together with Parkinson's disease dementia, DLB is one of the two Lewy body dementias. It is a common form of dementia, but the prevalence is not known accurately and many diagnoses are missed. The disease was first described on autopsy by Kenji Kosaka in 1976, and he named the condition several years later.

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD)—in which people lose the muscle paralysis (atonia) that normally occurs during REM sleep and act out their dreams—is a core feature. RBD may appear years or decades before other symptoms. Other core features are visual hallucinations, marked fluctuations in attention or alertness, and parkinsonism (slowness of movement, trouble walking, or rigidity). A presumptive diagnosis can be made if several disease features or biomarkers are present; the diagnostic workup may include blood tests, neuropsychological tests, imaging, and sleep studies. A definitive diagnosis usually requires an autopsy.

Most people with DLB do not have affected family members, although occasionally DLB runs in a family. The exact cause is unknown but involves formation of abnormal clumps of protein in neurons throughout the brain. Manifesting as Lewy bodies (discovered in 1912 by Frederic Lewy) and Lewy neurites, these clumps affect both the central and the autonomic nervous systems. Heart function and every level of gastrointestinal function—from chewing to defecation—can be affected, constipation being one of the most common symptoms. Low blood pressure upon standing can also occur. DLB commonly causes psychiatric symptoms, such as altered behavior, depression, or apathy.

DLB typically begins after the age of fifty, and people with the disease have an average life expectancy, with wide variability, of about four years after diagnosis. There is no cure or medication to stop the disease from progressing, and people in the latter stages of DLB may be unable to care for themselves. Treatments aim to relieve some of the symptoms and reduce the burden on caregivers. Medicines such as donepezil and rivastigmine can temporarily improve cognition and overall functioning, and melatonin can be used for sleep-related symptoms. Antipsychotics are usually avoided, even for hallucinations, because severe reactions occur in almost half of people with DLB, and their use can result in death. Management of the many different symptoms is challenging, as it involves multiple specialties and education of caregivers.

Classification and terminology

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia, a group of diseases involving progressive neurodegeneration of the central nervous system. It is one of the two Lewy body dementias, along with Parkinson's disease dementia.

Dementia with Lewy bodies can be classified in other ways. The atypical parkinsonian syndromes include DLB, along with other conditions. Also, DLB is a synucleinopathy, meaning that it is characterized by abnormal deposits of alpha-synuclein protein in the brain. The synucleinopathies include Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, and other rarer conditions.

The vocabulary of diseases associated with Lewy pathology causes confusion. Lewy body dementia (the umbrella term that encompasses the clinical diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia) differs from Lewy body disease (the term used to describe pathological findings of Lewy bodies on autopsy). Because individuals with Alzheimer's disease (AD) are often found on autopsy to also have Lewy bodies, DLB has been characterized as an Alzheimer disease-related dementia; the term Lewy body variant of Alzheimer disease is no longer used because the predominant pathology for these individuals is related to Alzheimer's. Even the term Lewy body disease may not describe the true nature of this group of diseases; a unique genetic architecture may predispose individuals to specific diseases with Lewy bodies, and naming controversies continue.

Signs and symptoms

DLB is dementia that occurs with "some combination of fluctuating cognition, recurrent visual hallucinations, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and parkinsonism", according to Armstrong (2019), when Parkinson's disease is not well established before the dementia occurs. DLB has widely varying symptoms and is more complex than many other dementias. Several areas of the nervous system (such as the autonomic nervous system and numerous regions of the brain) can be affected by Lewy pathology, in which the alpha-synuclein deposits cause damage and corresponding neurologic deficits.

In DLB, there is an identifiable set of early signs and symptoms; these are called the prodromal, or pre-dementia, phase of the disease. These early signs and symptoms can appear 15 years or more before dementia develops. The earliest symptoms are constipation and dizziness from autonomic dysfunction, hyposmia (reduced ability to smell), RBD, anxiety, and depression. RBD may appear years or decades before other symptoms. Memory loss is not always an early symptom.

Manifestations of DLB can be divided into essential, core, and supportive features. Dementia is the essential feature and must be present for diagnosis, while core and supportive features are further evidence in support of diagnosis (see diagnostic criteria below).

Essential feature

A dementia diagnosis is made after cognitive decline progresses to a point of interfering with normal daily activities, or social or occupational function. While dementia is an essential feature of DLB, it does not always appear early on, and is more likely to be present as the condition progresses.

Core features

While specific symptoms may vary, the core features of DLB are fluctuating cognition, alertness or attention; REM sleep behavior disorder; one or more of the cardinal features of parkinsonism, not due to medication or stroke; and repeated visual hallucinations.

The 2017 Fourth Consensus Report of the DLB Consortium determined these to be core features based on the availability of high-quality evidence indicating they are highly specific to the condition.

Fluctuating cognition and alertness

Fluctuations in cognitive function are the most characteristic feature of the Lewy body dementias. They are the most frequent symptom of DLB, and are often distinguishable from those of other dementias by concomitant fluctuations of attention and alertness, described by Tsamakis and Mueller (2021) as "spontaneous variations of cognitive abilities, alertness, or arousal". They are further distinguishable by a "marked amplitude between best and worst performances", according to McKeith (2002). These fluctuations vary in severity, frequency and duration; episodes last anywhere from seconds to weeks, interposed between periods of more normal functioning. When relatively lucid periods coincide with medical appointments, cognitive testing may inaccurately reflect disease severity, with subsequent assessments of cognition showing improvements from baseline.

Unlike the deficits in memory and orientation that are characteristic of Alzheimer disease, the distinct impairments in cognition seen in DLB are most commonly in three domains: attention, executive function, and visuospatial function. These fluctuating impairments are present early in the course of the disease. Individuals with DLB may be easily distracted, have a hard time focusing on tasks, or appear to be "delirium-like", "zoning out", or in states of altered consciousness with spells of confusion, agitation or incoherent speech. They may have disorganized speech and their ability to organize their thoughts may change during the day.

Executive function describes attentional and behavioral controls, memory and cognitive flexibility that aid problem solving and planning. Problems with executive function surface in activities requiring planning and organizing. Deficits can manifest in impaired job performance, inability to follow conversations, difficulties with multitasking, or mistakes in driving, such as misjudging distances or becoming lost.

The person with DLB may experience disorders of wakefulness or sleep disorders (in addition to REM sleep behavior disorder) that can be severe. These disorders include daytime sleepiness, drowsiness or napping more than two hours a day, insomnia, periodic limb movements, restless legs syndrome and sleep apnea.

REM sleep behavior disorder

REM sleep behavior disorderand dementia with Lewy bodies

—B. Tousi (2017), Diagnosis and Management of Cognitive and Behavioral Changes in Dementia With Lewy Bodies"REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) has been studied more thoroughly in correlation with DLB and is now considered a core feature. ... Basically, dementia in the presence of polysomnogram-confirmed RBD suggests possible DLB."

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a parasomnia in which individuals lose the paralysis of muscles (atonia) that is normal during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and consequently act out their dreams or make other abnormal movements or vocalizations. About 80% of those with DLB have RBD. Abnormal sleep behaviors may begin before cognitive decline is observed, and may appear decades before any other symptoms, often as the first clinical indication of DLB and an early sign of a synucleinopathy.

On autopsy, 94 to 98% of individuals with polysomnography-confirmed RBD have a synucleinopathy—most commonly DLB or Parkinson's disease in about equal proportions. More than three out of four people with RBD are diagnosed with a neurodegenerative condition within ten years, but additional neurodegenerative diagnoses may emerge up to 50 years after RBD diagnosis. RBD may subside over time.

Individuals with RBD may not be aware that they act out their dreams. RBD behaviors may include yelling, screaming, laughing, crying, unintelligible talking, nonviolent flailing, or more violent punching, kicking, choking, or scratching. The reported dream enactment behaviors are frequently violent, and involve a theme of being chased or attacked. People with RBD may fall out of bed or injure themselves or their bed partners, which may cause bruises, fractures, or subdural hematomas. Because people are more likely to remember or report violent dreams and behaviors—and to be referred to a specialist when injury occurs—recall or selection bias may explain the prevalence of violence reported in RBD.

Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is a clinical syndrome characterized by slowness of movement (called bradykinesia), rigidity, postural instability, and tremor; it is found in DLB and many other conditions like Parkinson's disease, Parkinson's disease dementia, and others. Parkinsonism occurs in more than 85% of people with DLB, who may have one or more of these cardinal features, although tremor at rest is less common.

Motor symptoms may include shuffling gait, problems with balance, falls, blank expression, reduced range of facial expression, and low speech volume or a weak voice. Presentation of motor symptoms is variable, but they are usually symmetric, presenting on both sides of the body. Only one of the cardinal symptoms of parkinsonism may be present, and the symptoms may be less severe than in persons with Parkinson's disease.

Visual hallucinations

Up to 80% of people with DLB have visual hallucinations, typically early in the course of the disease. They are recurrent and frequent; may be scenic, elaborate and detailed; and usually involve animated perceptions of animals or people, including children and family members. Examples of visual hallucinations "vary from 'little people' who casually walk around the house, 'ghosts' of dead parents who sit quietly at the bedside, to 'bicycles' that hang off of trees in the back yard".

These hallucinations can sometimes provoke fear, although their content is more typically neutral. In some cases, the person with DLB has insight that the hallucinations are not real. Among those with more disrupted cognition, the hallucinations can become more complex, and they may be less aware that their hallucinations are not real. Visual misperceptions or illusions are also common in DLB but differ from visual hallucinations. While visual hallucinations occur in the absence of real stimuli, visual illusions occur when real stimuli are incorrectly perceived; for example, a person with DLB may misinterpret a floor lamp for a person.

Supportive features

Supportive features of DLB have less diagnostic weight, but they provide evidence for the diagnosis. Supportive features may be present early in the progression, and persist over time; they are common but they are not specific to the diagnosis. The supportive features are:

- marked sensitivity to antipsychotics (neuroleptics);

- marked dysautonomia (autonomic dysfunction) in which the autonomic nervous system does not work properly;

- hallucinations in senses other than vision (hearing, touch, taste, and smell);

- hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness);

- hyposmia (reduced ability to smell);

- delusions (fixed false beliefs) organized around a common theme;

- postural instability, loss of consciousness, and frequent falls;

- apathy, anxiety, or depression.

Partly because of loss of cells that release the neurotransmitter dopamine, people with DLB may have neuroleptic malignant syndrome, impairments in cognition or alertness, or irreversible exacerbation of parkinsonism including severe rigidity, and dysautonomia from the use of antipsychotics.

Dysautonomia (autonomic dysfunction) occurs when Lewy pathology affects the peripheral autonomic nervous system (the nerves dealing with the unconscious functions of organs such as the intestines, heart, and urinary tract). The first signs of autonomic dysfunction are often subtle. Manifestations include blood pressure problems such as orthostatic hypotension (significantly reduced blood pressure upon standing) and supine hypertension (significantly elevated blood pressure when lying horizontally); constipation, urinary problems, and sexual dysfunction; loss of or reduced ability to smell; and excessive sweating, drooling, or salivation, and problems swallowing (dysphagia).

Alpha-synuclein deposits can affect cardiac muscle and blood vessels. "Degeneration of the cardiac sympathetic nerves is a neuropathological feature" of the Lewy body dementias, according to Yamada et al. Almost all people with synucleinopathies have cardiovascular dysfunction, although most are asymptomatic. Between 50 and 60% of individuals with DLB have orthostatic hypotension due to reduced blood flow, which can result in lightheadedness, feeling faint, and blurred vision.

From chewing to defecation, alpha-synuclein deposits affect every level of gastrointestinal function. Almost all persons with DLB have upper gastrointestinal tract dysfunction (such as gastroparesis, delayed gastric emptying) or lower gastrointestinal dysfunction (such as constipation and prolonged stool transit time). Persons with Lewy body dementia almost universally experience nausea, gastric retention, or abdominal distention from delayed gastric emptying. Problems with gastrointestinal function can affect medication absorption. Constipation can present a decade before diagnosis, and is one of the most common symptoms for people with Lewy body dementia. Dysphagia is milder than in other synucleinopathies and presents later. Urinary difficulties (urinary retention, waking at night to urinate, increased urinary frequency and urgency, and over- or underactive bladder) typically appear later and may be mild or moderate. Sexual dysfunction usually appears early in synucleinopathies, and may include erectile dysfunction and difficulty achieving orgasm or ejaculating.

Among the other supportive features, psychiatric symptoms are often present when the individual first comes to clinical attention and are more likely, compared to AD, to cause more impairment. About one-third of people with DLB have depression, and they often have anxiety as well. Anxiety leads to increased risk of falls, and apathy may lead to less social interaction.

Agitation, behavioral disturbances, and delusions typically appear later in the course of the disease. Delusions may have a paranoid quality, involving themes like a house being broken in to, infidelity, or abandonment. Individuals with DLB who misplace items may have delusions about theft. Capgras delusion may occur, in which the person with DLB loses knowledge of the spouse, caregiver, or partner's face, and is convinced that an imposter has replaced them. Hallucinations in other modalities are sometimes present, but are less frequent.

Sleep disorders (disrupted sleep cycles, sleep apnea, and arousal from periodic limb movement disorder) are common in DLB and may lead to hypersomnia. Loss of sense of smell may occur several years before other symptoms.

Causes

Like other synucleinopathies, the exact cause of DLB is unknown. No trigger for the build-up of alpha-synuclein deposits in the central nervous system has been conclusively identified. Synucleinopathies are typically caused by interactions of genetic and environmental influences; infectious causes have also been considered, but arguments in their favor are controversial and lacking in support. Most people with DLB do not have affected family members, although occasionally DLB runs in a family. The heritability of DLB is thought to be around 30% (that is, about 70% of disease severity is due to external factors or chance).

There is overlap in the genetic risk factors for DLB, Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease, and Parkinson's disease dementia. The APOE gene has three common variants. One, APOE ε4, is a risk factor for DLB and Alzheimer's disease, whereas APOE ε2 may be protective against both. Mutations in GBA, a gene for a lysosomal enzyme, are associated with both DLB and Parkinson's disease. Rarely, mutations in SNCA, the gene for alpha-synuclein, or LRRK2, a gene for a kinase enzyme, can cause any of DLB, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease or Parkinson's disease dementia. This suggests some shared genetic pathology may underlie all four diseases.

The greatest risk of developing DLB is being over the age of 50. Having REM sleep behavior disorder or Parkinson's disease confers a higher risk for developing DLB. The risk of developing DLB has not been linked to any specific lifestyle factors. Risk factors for rapid conversion of RBD to a synucleinopathy include impairments in color vision or the ability to smell, mild cognitive impairment, and abnormal dopaminergic imaging.

Pathophysiology

DLB is characterized by the development of abnormal collections of alpha-synuclein protein within diseased brain neurons, manifesting as Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. When these clumps of protein form, neurons function less optimally and eventually die. Neuronal loss in DLB leads to profound dopamine dysfunction and marked cholinergic pathology; other neurotransmitters might be affected, but less is known about them. Damage in the brain is widespread, and affects many domains of functioning.

Loss of acetylcholine-producing neurons is thought to account for degeneration in memory and learning, while the death of dopamine-producing neurons appears to be responsible for degeneration of behavior, cognition, mood, movement, motivation, and sleep. The extent of Lewy body neuronal damage is a key determinant of dementia in the Lewy body disorders.

The precise mechanisms contributing to DLB are not well understood and are a matter of some controversy. The role of alpha-synuclein deposits is unclear, because individuals with no signs of DLB have been found on autopsy to have advanced alpha-synuclein pathology. The relationship between Lewy pathology and widespread cell death is contentious. It is not known if the pathology spreads between cells or follows another pattern. The mechanisms that contribute to cell death, how the disease advances through the brain, and the timing of cognitive decline are all poorly understood. There is no model to account for the specific neurons and brain regions that are affected.

Autopsy studies and amyloid imaging studies using Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) indicate that tau protein pathology and amyloid plaques, which are hallmarks of AD, are also common in DLB and more common than in Parkinson's disease dementia. Amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposits are found in the tauopathies—neurodegenerative diseases characterized by neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein—but the mechanism underlying dementia is often mixed, and Aβ is also a factor in DLB.

A proposed pathophysiology for RBD implicates neurons in the reticular formation that regulate REM sleep. RBD might appear decades earlier than other symptoms in the Lewy body dementias because these cells are affected earlier, before spreading to other brain regions.

Diagnosis

Dementia with Lewy bodies can only be definitively diagnosed after death with an autopsy of the brain (or in rare familial cases, via a genetic test), so diagnosis of the living is referred to as probable or possible.

Diagnosing DLB can be challenging because of the wide range of symptoms with differing levels of severity in each individual. DLB is often misdiagnosed or, in its early stages, confused with Alzheimer's disease. The majority of individuals with Lewy body dementias receive an inaccurate initial diagnosis—such as Alzheimer's, parkinsonism, other dementias or a psychiatric diagnosis—resulting in reduced support and increased fear and uncertainty, sometimes for many years. Comparing the rates of detection of DLB in autopsy studies to those diagnosed while in clinical care indicates that as many as one in three diagnoses of DLB may be missed. Another complicating factor is that DLB commonly occurs along with Alzheimer's; autopsy reveals that half of people with DLB have some level of changes attributed to AD in their brains, which contributes to the wide-ranging variety of symptoms and diagnostic difficulty.

Living with an uncertain diagnosis and prognosis is a concern expressed by both individuals with DLB and their caregivers and difficulty gaining a diagnosis and differing interactions with healthcare professionals are common experiences; once diagnosed, there are still difficulties finding a doctor knowledgeable in treating DLB. Despite the difficulty in diagnosis, a prompt diagnosis is important because of the serious risks of sensitivity to antipsychotics and the need to inform both the person with DLB and the person's caregivers about those medications' side effects. The management of DLB is difficult in comparison to many other neurodegenerative diseases, so an accurate diagnosis is important.

Criteria

The 2017 Fourth Consensus Report established diagnostic criteria for probable and possible DLB, recognizing advances in detection since the earlier Third Consensus (2005) version. The 2017 criteria are based on essential, core, and supportive clinical features, and diagnostic biomarkers.

The essential feature is dementia; for a DLB diagnosis, it must be significant enough to interfere with social or occupational functioning.

The four core clinical features (described in the Signs and symptoms section) are fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder, and signs of parkinsonism. Supportive clinical features are marked sensitivity to antipsychotics; marked autonomic dysfunction; nonvisual hallucinations; hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness); hyposmia (reduced ability to smell); false beliefs and delusions organized around a common theme; postural instability, loss of consciousness and frequent falls; and apathy, anxiety, or depression.

Direct laboratory-measurable biomarkers for DLB diagnosis are not known, but several indirect methods can lend further evidence for diagnosis. The indicative diagnostic biomarkers are: reduced dopamine transporter uptake in the basal ganglia shown on PET or SPECT imaging; low uptake of iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine (I-MIBG) shown on myocardial scintigraphy; and loss of atonia during REM sleep evidenced on polysomnography. Supportive diagnostic biomarkers (from PET, SPECT, CT, or MRI brain imaging studies or EEG monitoring) are: lack of damage to medial temporal lobe (damage is more likely in AD); reduced occipital activity; and prominent slow-wave activity on EEG.

Probable DLB can be diagnosed when dementia and at least two core features are present, or when one core feature and at least one indicative biomarker are present. Possible DLB can be diagnosed when dementia and only one core feature are present or, if no core features are present, then at least one indicative biomarker is present.

DLB is distinguished from Parkinson's disease dementia by the time frame in which dementia symptoms appear relative to parkinsonian symptoms. DLB is diagnosed when cognitive symptoms begin before or at the same time as parkinsonian motor signs. Parkinson's disease dementia would be the diagnosis when Parkinson's disease is well established before the dementia occurs (the onset of dementia is more than a year after the onset of parkinsonian symptoms). Known as the one-year rule, the distinction is acknowledged to be arbitrary; it recognizes overlap between the conditions along with key differences, while allowing for variations in treatment and prognosis and providing a framework for research.

DLB is listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as major or mild neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies. The differences between the DSM and DLB Consortium diagnostic criteria are: 1) the DSM does not include low dopamine transporter uptake as a supportive feature, and 2) unclear diagnostic weight is assigned to biomarkers in the DSM. Lewy body dementias are classified by the World Health Organization in its ICD-11, the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, in chapter 06, as neurodevelopmental disorders, code 6D82.

Clinical history and testing

Diagnostic tests can be used to establish some features of the condition and distinguish them from symptoms of other conditions. Diagnosis may include taking the person's medical history, a physical exam, assessment of neurological function, brain imaging, neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive function, sleep studies, myocardial scintigraphy, or laboratory testing to rule out conditions that may cause symptoms similar to dementia, such as abnormal thyroid function, syphilis, HIV, and vitamin deficiencies.

Typical dementia screening tests used are the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). The pattern of cognitive impairment in DLB is distinct from other dementias, such as AD; the MMSE mainly tests for the memory and language impairments more commonly seen in those other dementias and may be less suited for assessing cognition in the Lewy body dementias, where testing of visuospatial and executive function is indicated. The MoCA may be better suited to assessing cognitive function in DLB, and the Clinician Assessment of Fluctuation scale and the Mayo Fluctuation Composite Score may help understand cognitive decline relative to fluctuations in DLB. For tests of attention, digit span, serial sevens, and spatial span can be used for simple screening, and the Revised Digit Symbol Subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale may show defects in attention that are characteristic of DLB. The Frontal Assessment Battery, Stroop test and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test are used for evaluation of executive function, and there are many other screening instruments available.

If DLB is suspected when parkinsonism and dementia are the only presenting features, PET or SPECT imaging may show reduced dopamine transporter activity. A DLB diagnosis may be warranted if other conditions with reduced dopamine transporter uptake can be ruled out.

RBD is diagnosed either by sleep study recording or, when sleep studies cannot be performed, by medical history and validated questionnaires. In individuals with dementia and a history of RBD, a probable DLB diagnosis can be justified (even with no other core feature or biomarker) based on a sleep study showing REM sleep without atonia because it is so highly predictive. Conditions similar to RBD, like severe sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder, must be ruled out. Prompt evaluation and treatment of RBD is indicated when a prior history of violence or injury is present as it may increase the likelihood of future violent dream enactment behaviors. Individuals with RBD may not be able to provide a history of dream enactment behavior, so bed partners are also consulted. The REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Single-Question Screen offers diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in the absence of polysomnography with one question: "Have you ever been told, or suspected yourself, that you seem to 'act out your dreams' while asleep (for example, punching, flailing your arms in the air, making running movements, etc.)?" Because some individuals with DLB do not have RBD, normal findings from a sleep study cannot rule out DLB.

Since 2001, iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine (I-MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy has been used diagnostically in East Asia (principally Japan), but not in the US; studies validating its use in differential diagnoses are lacking as of 2022. MIBG is taken up by sympathetic nerve endings, such as those that innervate the heart, and is labeled for scintigraphy with radioactive iodine. Autonomic dysfunction resulting from damage to nerves in the heart in patients with DLB is associated with lower cardiac uptake of I-MIBG.

There is no genetic test to determine if an individual will develop DLB and, according to the Lewy Body Dementia Association, genetic testing is not routinely recommended because there are only rare instances of hereditary DLB.

Differential

Many neurodegenerative conditions share cognitive and motor symptoms with dementia with Lewy bodies. The differential diagnosis includes Alzheimer's disease; such synucleinopathies as Parkinson's disease dementia, Parkinson's disease, and multiple system atrophy; vascular dementia; and progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, and corticobasal syndrome.

The symptoms of DLB are easily confused with delirium, or more rarely with psychosis; prodromal subtypes of delirium-onset DLB and psychiatric-onset DLB have been proposed. Mismanagement of delirium is a particular concern because of the risks to people with DLB associated with antipsychotics. A careful examination for features of DLB is warranted in individuals with unexplained delirium. PET or SPECT imaging showing reduced dopamine transporter uptake can help distinguish DLB from delirium.

Lewy pathology affects the peripheral autonomic nervous system; autonomic dysfunction is observed less often in AD, frontotemporal, or vascular dementias, so its presence can help differentiate them. MRI scans almost always show abnormalities in the brains of people with vascular dementia, which can begin suddenly.

Alzheimer's disease

DLB is distinguishable from AD even in the prodromal phase. Short-term memory impairment is seen early in AD and is a prominent feature, while fluctuating attention is uncommon; impairment in DLB is more often seen first as fluctuating cognition. In contrast to AD—in which the hippocampus is among the first brain structures affected, and episodic memory loss related to encoding of memories is typically the earliest symptom—memory impairment occurs later in DLB. People with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (in which memory loss is the main symptom) may progress to AD, whereas those with non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment (which has more prominent impairments in language, visuospatial, and executive domains) are more likely to progress towards DLB. Memory loss in DLB has a different progression from AD because frontal structures are involved earlier, with later involvement of temporoparietal brain structures. Verbal memory is not as severely affected as in AD.

Medical imaging in AD and DLB MRI of brain showing hippocampus atrophy (red rectangles), more prominent in AD than DLB, compared to normal control (NC)

MRI of brain showing hippocampus atrophy (red rectangles), more prominent in AD than DLB, compared to normal control (NC) FDG-PET horizontal cross section of brain, with brighter areas indicating higher metabolism. The cingulate island sign is indicated by the arrowhead.

FDG-PET horizontal cross section of brain, with brighter areas indicating higher metabolism. The cingulate island sign is indicated by the arrowhead. FDG-PET of brain surface, with the color red indicating areas of high metabolism. The occipital lobe in DLB (arrows) shows less activity than in AD.

FDG-PET of brain surface, with the color red indicating areas of high metabolism. The occipital lobe in DLB (arrows) shows less activity than in AD.

While 74% of people with autopsy-confirmed DLB had deficits in planning and organization, they show up in only 45% of people with AD. Visuospatial processing deficits are present in most individuals with DLB, and they show up earlier and are more pronounced than in AD. Hallucinations typically occur early in the course of DLB, are less common in early AD, but usually occur later in AD. AD pathology frequently co-occurs in DLB and is associated with more rapid decline; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing may reveal an "Alzheimer's pattern" of higher tau and lower amyloid beta.

PET or SPECT imaging can be used to detect reduced dopamine transporter uptake and distinguish AD from DLB. Severe atrophy of the hippocampus is more typical of AD than DLB. Before dementia develops (during the mild cognitive impairment phase), MRI scans show normal hippocampal volume. After dementia develops, MRI shows more atrophy among individuals with AD, and a slower reduction in volume over time among people with DLB than those with AD. Compared to people with AD, FDG-PET brain scans in people with DLB often show a cingulate island sign.

In East Asia, particularly Japan,I-MIBG is used in the differential diagnosis of DLB and AD, because reduced labeling of cardiac nerves is seen only in Lewy body disorders. Other indicative and supportive biomarkers are useful in distinguishing DLB and AD (preservation of medial temporal lobe structures, reduced occipital activity, and slow-wave EEG activity).

Synucleinopathies

Dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia are clinically similar after dementia occurs in Parkinson's disease. Delusions in Parkinson's disease dementia are less common than in DLB, and persons with Parkinson's disease are typically less caught up in their visual hallucinations than those with DLB. There is a lower incidence of tremor at rest in DLB than in Parkinson's disease, and signs of parkinsonism in DLB are more symmetrical. In multiple system atrophy, autonomic dysfunction appears earlier and is more severe, and is accompanied by uncoordinated movements, while visual hallucinations and fluctuating cognition are less common than in DLB. Urinary difficulty is one of the earliest symptoms with multiple system atrophy, and is often severe.

Frontotemporal dementias

Corticobasal syndrome, corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy are frontotemporal dementias with features of parkinsonism and impaired cognition. Similar to DLB, imaging may show reduced dopamine transporter uptake. Corticobasal syndrome and degeneration, and progressive supranuclear palsy, are usually distinguished from DLB by history and examination. Motor movements in corticobasal syndrome are asymmetrical. There are differences in posture, gaze and facial expressions in the most common variants of progressive supranuclear palsy, and falling backwards is more common relative to DLB. Visual hallucinations and fluctuating cognition are unusual in corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Management

Palliative care is offered to ameliorate symptoms, but there are no medications that can slow, stop, or improve the relentless progression of the disease. No medications for DLB are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as of 2023, although donepezil is licensed in Japan and the Philippines for the treatment of DLB. As of 2020, there has been little study on the best management for non-motor symptoms such as sleep disorders and autonomic dysfunction; most information on management of autonomic dysfunction in DLB is based on studies of people with Parkinson's disease.

Management can be challenging because of the need to balance treatment of different symptoms: cognitive dysfunction, neuropsychiatric features, impairments related to the motor system, and other nonmotor symptoms. Individuals with DLB have widely different symptoms that fluctuate over time, and treating one symptom can worsen another; suboptimal care can result from a lack of coordination among the physicians treating different symptoms. A multidisciplinary approach—going beyond early and accurate diagnosis to include educating and supporting the caregivers—is favored.

Medication

Antipsychotic sensitivity—B.P. Boot (2015), Comprehensive treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies"The most fraught decision in the management of DLB relates to the use of antipsychotic medications ... DLB patients are particularly at risk of antipsychotic medication morbidity and mortality."

Pharmacological management of DLB is complex because of adverse effects of medications and the wide range of symptoms to be treated (cognitive, motor, neuropsychiatric, autonomic, and sleep). Anticholinergic and dopaminergic agents can have adverse effects or result in psychosis in individuals with DLB, and a medication that addresses one feature might worsen another. For example, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) for cognitive symptoms can lead to complications in dysautonomia features; treatment of movement symptoms with dopamine agonists may worsen neuropsychiatric symptoms; and treatment of hallucinations and psychosis with antipsychotics may worsen other symptoms or lead to a potentially fatal reaction.

Extreme caution is required in the use of antipsychotic medication in people with DLB because of their sensitivity to these agents. Severe and life-threatening reactions occur in almost half of people with DLB, and can be fatal after a single dose. Antipsychotics with D2 dopamine receptor-blocking properties are used only with great caution. According to Boot (2013), "electing not to use neuroleptics is often the best course of action". People with Lewy body dementias who take neuroleptics are at risk for neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a life-threatening illness. There is no evidence to support the use of antipsychotics to treat the Lewy body dementias, and they carry the additional risk of stroke when used in the elderly with dementia.

Medications (including tricyclic antidepressants and treatments for urinary incontinence) with anticholinergic properties that cross the blood–brain barrier can cause memory loss. The antihistamine medication diphenhydramine (Benadryl), sleep medications like zolpidem, and benzodiazepines may worsen confusion or neuropsychiatric symptoms. Some general anesthetics may cause confusion or delirium upon waking in persons with Lewy body dementias, and may result in permanent decline.

Cognitive symptoms

There is strong evidence for the use of AChEIs to treat cognitive problems; these medications include rivastigmine and donepezil. Both are first-line treatments in the UK. Even when the AChEIs do not lead to improvement in cognitive symptoms, people taking them may have less deterioration overall, although there may be adverse gastrointestinal effects. The use of these medications can reduce the burden on caregivers and improve activities of daily living for the individual with DLB. The AChEIs are initiated carefully as they may aggravate autonomic dysfunction or sleep behaviors. There is less evidence for the efficacy of memantine in DLB, but it may be used alone or with an AChEI because of its low side effect profile. Anticholinergic drugs are avoided because they worsen cognitive symptoms.

To improve daytime alertness, there is mixed evidence for the use of stimulants such as methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine; although worsening of neuropsychiatric symptoms is not common, they can increase the risk of psychosis. Modafinil and armodafinil may be effective for daytime sleepiness.

Motor symptoms

Motor symptoms in DLB appear to respond somewhat less to medications used to treat Parkinson's disease, like levodopa, and these medications can increase neuropsychiatric symptoms. Almost one out of every three individuals with DLB develops psychotic symptoms from levodopa. If such medications are needed for motor symptoms, cautious introduction with slow increases to the lowest possible dose may help avoid psychosis.

The anticonvulsant zonisamide has been approved in Japan since 2009 for treating Parkinson's disease and since 2018 to treat parkinsonism in DLB. There is high certainty according to the GRADE certainty rating approach that it is effective for treating motor symptoms in DLB.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

Neuropsychiatric symptoms of DLB (aggression, anxiety, apathy, delusions, depression and hallucinations) do not always require treatment. The first line of defense in decreasing visual hallucinations is to reduce the use of dopaminergic drugs, which can worsen hallucinations. If new neuropsychiatric symptoms appear, the use of medications (such as anticholinergics, tricyclic antidepressants, benzodiazepines and opioids) that might be contributing to these symptoms is reviewed.

Among the AChEIs, donepezil and rivastigmine can help reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and improve the frequency and severity of hallucinations in the less severe stages of DLB. For treating psychosis and agitation in DLB, there is low evidence for memantine, olanzapine and aripiprazole, and very low evidence for the efficacy of quetiapine. Although clozapine has been shown effective in Parkinson's disease, there is very low evidence for its use to treat visual hallucinations in DLB, and its use requires regular blood monitoring.

Apathy may be treated with AChEIs, and they may also reduce hallucinations, delusions, anxiety and agitation. Most medications to treat anxiety and depression have not been adequately investigated for DLB. Antidepressants may affect sleep and worsen RBD. Mirtazapine and SSRIs can be used to treat depression, depending on how well they are tolerated, and guided by general advice for the use of antidepressants in dementia. Antidepressants with anticholinergic properties may worsen hallucinations and delusions. People with Capgras syndrome may not tolerate AChEIs.

Sleep disorders

The first steps in managing sleep disorders are to evaluate the use of medications that impact sleep and provide education about sleep hygiene. Sleep medications are carefully evaluated for each individual as they carry increased risk of falls, increased daytime sleepiness, and worsening cognition.

Injurious dream enactment behaviors are a treatment priority. Frequency and severity of RBD may be lessened by treating sleep apnea, if it is present. RBD may be treated with melatonin or clonazepam. Melatonin may be more helpful in preventing injuries, and it offers a safer alternative, because clonazepam can produce deteriorating cognition, and worsen sleep apnea.

Memantine is useful for some people. Modafinil may be used for hypersomnia, but no trials support its use in DLB. Antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs, tricyclics, and MAOIs), AChEIs, beta blockers, caffeine, and tramadol may worsen RBD.

Autonomic symptoms

Decreasing the dosage of dopaminergic or atypical antipsychotic drugs may be needed with orthostatic hypotension, and high blood pressure drugs can sometimes be stopped. When non-pharmacological treatments for orthostatic hypotension have been exhausted, fludrocortisone, droxidopa, or midodrine are options, but these drugs have not been specifically studied for DLB as of 2020. Delayed gastric emptying can be worsened by dopaminergic medications, and constipation can be worsened by opiates and anticholinergic medications. Muscarinic antagonists used for urinary symptoms might worsen cognitive impairment in people with Lewy body dementias.

Other

There is no high-quality evidence for non-pharmacological management of DLB, but some interventions have been shown effective for addressing similar symptoms that occur in other dementias. For example, organized activities, music therapy, physical activity and occupational therapy may help with psychosis or agitation, while exercise and gait training can help with motor symptoms. Cognitive behavioral therapy can be tried for depression or hallucinations, although there is no evidence for its use in DLB. Cues can be used to help with memory retrieval.

For autonomic dysfunction, several non-medication strategies may be helpful. Dietary changes include avoiding meals high in fat and sugary foods, eating smaller and more frequent meals, after-meal walks, and increasing fluids or dietary fiber to treat constipation. Stool softeners and exercise also help with constipation. Excess sweating can be helped by avoiding alcohol and spicy foods, and using cotton bedding and loose fitting clothing.

Physical exercise in a sitting or recumbent position, and exercise in a pool, can help maintain conditioning. Compression stockings and elevating the head of the bed may also help, and increasing fluid intake or table salt can be tried to reduce orthostatic hypotension. To lessen the risk of fractures in individuals at risk for falls, bone mineral density screening and testing of vitamin D levels are used, and caregivers are educated on the importance of preventing falls. Physiotherapy has been shown helpful for Parkinson's disease dementia, but as of 2020, there is no evidence to support physical therapy in people with DLB.

Caregiving

Further information: Caring for people with dementiaDemands placed on caregivers are higher than in AD because of the neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with DLB. Contributing factors to the caregiver burden in DLB are emotional fluctuations, apathy, psychosis, aggression, agitation, and night-time behaviors such as parasomnias, that lead to a loss of independence earlier than in AD. Caregivers may experience depression and exhaustion, and they may need support from other people. Other family members who are not present in the daily caregiving may not observe the fluctuating behaviors or recognize the stress on the caregiver, and conflict can result when family members are not supportive.

Teaching caregivers how to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms (such as agitation and psychosis) is recommended, although education for caregivers has not been studied as thoroughly as in AD or Parkinson's disease. Caregiver education reduces not only distress for the caregiver, but symptoms for the individual with dementia. Caregiver training, watchful waiting, identifying sources of pain, and increasing social interaction can help minimize agitation. Individuals with dementia may not be able to communicate that they are in pain, and pain is a common trigger of agitation.

Visual hallucinations associated with DLB create a particular burden on caregivers. Caregivers can be educated to distract or change the subject when confronted with hallucinations, and that this is more effective than arguing over the reality of the hallucination. Coping strategies may help and are worth trying, even though there is no evidence for their efficacy. These strategies include having the person with DLB look away or look at something else, focus on or try to touch the hallucination, wait for it to go away on its own, and speak with others about the visualization. Delusions and hallucinations may be reduced by increasing lighting in the evening, and making sure there is no light at night when the individual with DLB is sleeping.

With the increased risk of side effects from antipsychotics for people with DLB, educated caregivers are able to act as advocates for the person with DLB. If evaluation or treatment in an emergency room is needed, the caregiver may be able to explain the risks associated with neuroleptic use for persons with DLB. Medical alert bracelets or notices about medication sensitivity are available and can save lives.

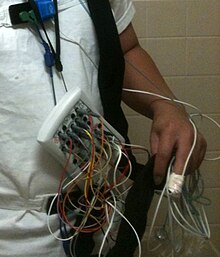

Individuals and their caregivers can be counselled about the need to improve bedroom safety for RBD symptoms. Sleep-related injuries from falling or jumping out of bed can be avoided by lowering the height of the bed, placing a mattress next to the bed to soften the impact of a fall, and removing sharp objects from around the bed. Sharp surfaces near the bed can be padded, bed alarm systems may help with sleepwalking, and bed partners may find it safer to sleep in another room. According to St Louis and Boeve, firearms should be locked away, out of the bedroom.

A home safety assessment can be done when there is risk of falling. Handrails and shower chairs can help avoid falls. Driving ability may be impaired early in DLB because of visual hallucinations, movement issues related to parkinsonism, and fluctuations in cognitive ability, and at some point it becomes unsafe for the person to drive. Driving ability is assessed as part of management, and family members generally determine when driving privileges are removed.

Prognosis

As of 2021, no cure is known for DLB. The prognosis for DLB has not been well studied; early studies had methodological limitations, such as small sample size and selection bias. Relative to AD and other dementias, DLB generally leads to higher rates of disability, hospitalization and institutionalization, and lower life expectancy and quality of life, with increased costs of care. Depression, apathy, and visual hallucinations contribute to the reduced quality of life. Decline may be more rapid when the APOE gene is present, or when AD—or its biomarkers—is also present. The severity of orthostatic hypotension also predicts a worse prognosis. Visuospatial deficits early in the course of DLB were thought to be a predictor of rapid decline, but more recent studies did not find an association.

The trajectory of cognitive decline in DLB is difficult to establish because of the high rate of missed diagnoses; the typical delay of a year in the US, and 1.2 years in the UK, for diagnosis of DLB mean that a baseline from which deterioration can be measured is often absent. Compared to AD, which is better studied, memory is thought to be retained longer, while verbal fluency may be lost faster, but the most common tools used to assess cognition may miss the most common cognitive deficits in DLB, and better studies are needed. There are more neuropsychiatric symptoms in DLB than AD, and they may emerge earlier, so those with DLB may have a less favorable prognosis, with more rapid cognitive decline, more admissions to residential care, and a lower life expectancy. An increased rate of hospitalization compared to AD is most commonly related to hallucinations and confusion, followed by falls and infection.

Life expectancy is difficult to predict, and limited study data are available. Survival may be defined from the point of disease onset, or from the point of diagnosis. There is wide variability in survival times, as DLB may be rapidly or slowly progressing. A 2019 meta-analysis found an average survival time after diagnosis of 4.1 years—indicating survival in DLB 1.6 years less than after a diagnosis of Alzheimer's. A 2017 review found survival from disease onset between 5.5 and 7.7 years, and survival from diagnosis between 1.9 and 6.3 years. The difference in survival between AD and DLB could be because DLB is harder to diagnose, and may be diagnosed later in the course of the disease. An online survey with 658 respondents found that, after diagnosis, more than 10% died within a year, 10% lived more than 7 years, and some live more than 10 years; some people with Lewy body dementias live for 20 years. Shorter life expectancy is more likely when visual hallucinations, abnormal gait, and variable cognition are present early on.

Fear and anxiety feature strongly for both people with Lewy body dementia and their caregivers; a range of emotional responses to living with Lewy bodies includes fear of hallucinations, fear of falls and frightening nightmares as a result of RBD, and being fearful of the effects of tiredness and fatigue. The symptoms of fluctuations, depression, delirium and violence are also experienced as frightening. An immense amount of physical support from friends and family is often required to maintain social and supporting relationships. Individuals with Lewy body dementias describe feeling a burden in the wider social context, as they reduce attending social events due to their increasing physical needs. Frequently reported burden dimensions include personal strain and interference with personal life, which can lead to relationship dissatisfaction and resentment.

In the late phase of the disease, people may be unable to care for themselves. Falls—caused by many factors including parkinsonism, dysautonomia, and frailness—increase morbidity and mortality. Failure to thrive and aspiration pneumonia, a complication of dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) that results from dysautonomia, commonly cause death among people with the Lewy body dementias. Cardiovascular disease and sepsis are also common causes of death.

Epidemiology

The Lewy body dementias are as a group the second most common form of neurodegenerative dementia after AD as of 2021. DLB itself is one of the three most common types of dementia, along with AD and vascular dementia.

The diagnostic criteria for DLB before 2017 were highly specific, but not very sensitive, so that more than half of cases were missed historically. Dementia with Lewy bodies was under-recognized as of 2021, and there is little data on its epidemiology. The incidence and prevalence of DLB are not known accurately, but estimates are increasing with better recognition of the condition since 2017.

About 0.4% of those over the age of 65 are affected with DLB, and between 1 and 4 per 1,000 people develop the condition each year. Symptoms usually appear between the ages of 50 and 80 (median 76), and it is not uncommon for it to be diagnosed before the age of 65.

DLB is thought to be slightly more common in men than women, but this finding has been challenged and is inconsistent across studies. Women may be over-represented in community samples and under-represented in clinical populations, where RBD is more frequently diagnosed in men; the diagnosis appears to have a higher prevalence for men in those under 75, while women appear to be diagnosed later and with greater cognitive impairment. Studies in Japan, France and Britain show a more equal prevalence between men and women than in the US.

An estimated 10 to 15% of diagnosed dementias are Lewy body type, but estimates range as high as 23% for those in clinical studies. A French study found an incidence among persons 65 years and older almost four times higher than a US study (32 US vs 112 France per 100,000 person-years), but the US study may have excluded people with only mild or no parkinsonism, while the French study screened for parkinsonism. Neither of the studies assessed systematically for RBD, so DLB may have been underdiagnosed in both studies. A door-to-door study in Japan found a prevalence of 0.53% for persons 65 and older, and a Spanish study found similar results.

History

Frederic Lewy (1885–1950) was the first to discover the abnormal protein deposits in the early 1900s. In 1912, studying Parkinson's disease (paralysis agitans), he described findings of these inclusion bodies in the vagus nerve, the nucleus basalis of Meynert and other brain regions. He published a book, The Study on Muscle Tone and Movement. Including Systematic Investigations on the Clinic, Physiology, Pathology, and Pathogenesis of Paralysis agitans, in 1923 and except for one brief paper a year later, never mentioned his findings again.

In 1961, Okazaki et al. published an account of diffuse Lewy-type inclusions associated with dementia in two autopsied cases. Dementia with Lewy bodies was fully described in an autopsied case by Japanese psychiatrist and neuropathologist Kenji Kosaka in 1976. Kosaka first proposed the term Lewy body disease four years later, based on 20 autopsied cases. DLB was thought to be rare until it became easier to diagnose in the 1980s after the discovery of alpha-synuclein immunostaining that highlighted Lewy bodies in post mortem brains. Kosaka et al. described thirty-four more cases in 1984, which were mentioned along with four UK cases by Gibb et al. in 1987 in the journal Brain, bringing attention to the Japanese work in the Western world. A year later, Burkhardt et al. published the first general description of diffuse Lewy body disease.

In the 1990s, with Japanese, UK, and US researchers finding that DLB was a common dementia, there were still no available diagnostic guidelines, with each group using different terminology. The different groups of researchers began to realize that a collaborative approach was needed if research was to advance. The DLB Consortium was established, and, in 1996, the term dementia with Lewy bodies was agreed upon, and the first criteria for diagnosing DLB were elaborated.

Two 1997 discoveries highlighted the importance of Lewy body inclusions in neurodegenerative processes: a mutation in the SNCA gene that encodes the alpha-synuclein protein was found in kindreds with Parkinson's disease, and Lewy bodies and neurites were found to be immunoreactive for alpha-synuclein. Thus, alpha-synuclein aggregation was established as the primary building block of the synucleinopathies.

Between 1995 and 2005, the DLB Consortium issued three consensus reports on DLB. DLB was included in the fourth text revision of the DSM (DSM-IV-TR, published in 2000) under "Dementia due to other general medical conditions". In the 2010s, the possibility of a genetic basis for LBD began to emerge. The Fourth Consensus Report was issued in 2017, giving increased diagnostic weighting to RBD and I-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy.

Society and culture

Main article: Lewy body dementia § Society and culture

The British author and poet Mervyn Peake died in 1968 and was diagnosed posthumously as a probable case of DLB in a 2003 study published in JAMA Neurology. Based on signs in his work and letters of progressive deterioration, fluctuating cognitive decline, deterioration in visuospatial function, declining attention span, and visual hallucinations and delusions, his may be the earliest known case where DLB was found to have been the likely cause of death.

At the time of his suicide on August 11, 2014, Robin Williams, the American actor and comedian, had been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. According to his widow, Williams had experienced depression, anxiety, and increasing paranoia. His widow said that his autopsy found diffuse Lewy body disease, while the autopsy used the term diffuse Lewy body dementia. Dennis Dickson, a spokesperson for the Lewy Body Dementia Association, clarified the distinction by stating that diffuse Lewy body dementia is more commonly called diffuse Lewy body disease and refers to the underlying disease process. According to Dickson, "Lewy bodies are generally limited in distribution, but in DLB, the Lewy bodies are spread widely throughout the brain, as was the case with Robin Williams." Ian G. McKeith, professor and researcher of Lewy body dementias, commented that Williams' symptoms and autopsy findings were explained by DLB.

Research directions

The identification of prodromal biomarkers for DLB will enable treatments to begin sooner, improve the ability to select subjects and measure efficacy in clinical trials, and help families and clinicians plan for early interventions and awareness of potential adverse effects from the use of antipsychotics. Criteria were established in 2020 to help researchers better recognize DLB in the pre-dementia phase. Three syndromes of prodromal DLB have been proposed: 1) mild cognitive impairment with Lewy bodies (MCI-LB); 2) delirium-onset DLB; and 3) psychiatric-onset DLB. The three early syndromes may overlap. As of 2020, the DLB Diagnostic Study Group's position is that criteria for MCI-LB can be recommended, but that it remains difficult to distinguish delirium-onset and psychiatric-onset DLB without better biomarkers. Nonetheless, severe late-onset psychiatric disorders can be an indication to consider Lewy body dementia, and unexplained delirium raises the possibility of prodromal DLB.

The diagnosis of DLB is made using the DLB Consortium criteria, but a 2017 study of skin samples from 18 people with DLB found that all of them had deposits of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein, while none of the controls did, suggesting that skin samples offer diagnostic potential. Other potential biomarkers under investigation are quantitative electroencephalography, imaging examination of brain structures, and measures of synucleinopathy in CSF. While commercial skin biopsy tests for DLB are available in the US, and the FDA has given a 'breakthrough device' authorization for CSF testing, these tests are not widely available and their role in clinical practice has not been established as of 2022. Other tests to detect alpha-synuclein with blood tests are under study as of 2021.

Cognitive training, deep brain stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation have been studied more in Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease than they have in dementia with Lewy bodies, and all are potential therapies for DLB. Four clinical trials for treating parkinsonian symptoms in DLB have been completed as of 2021, but more studies are needed to assess risk vs. benefits, adverse effects, and longer-term therapeutic protocols.

Strategies for future interventions involve modifying the course of the disease using immunotherapy, gene therapy, and stem cell therapy, and reducing amyloid beta and alpha-synuclein accumulation. Therapies under study as of 2019 aim to reduce brain levels of alpha-synuclein (with the pharmaceuticals ambroxol, NPT200-11, and E2027), or to use immunotherapy to reduce widespread neuroinflammation resulting from alpha-synuclein deposits.

Notes

- ^ Areas of the brain and functions affected:

- cerebral cortex – thought, perception and language;

- limbic cortex – emotions and behavior;

- hippocampus – memory;

- midbrain and basal ganglia – movement;

- brain stem – sleep, alertness, and autonomic dysfunction;

- olfactory cortex – smell.

- The European Federation of Neurological Societies—European Neurological Society and the British Association for Psychopharmacology also have diagnostic guidelines, but they were not developed specifically for DLB, hence the DLB Consortium guidelines are the most widely used and cited.

- Questionnaires such as the REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Screening Questionnaire (RBDSQ), the REM Sleep Behavior Questionnaires – Hong-Kong (RBD-HK), the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire (MSQ), the Innsbruck REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Inventory, and the REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Single-Question Screen are well-validated.

- Kosaka (2017) writes: "Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is now well known to be the second most frequent dementia following Alzheimer disease (AD). Of all types of dementia, AD is known to account for about 50%, DLB about 20% and vascular dementia (VD) about 15%. Thus, AD, DLB, and VD are now considered to be the three major dementias." The NINDS (2020) says that Lewy body dementia "is one of the most common causes of dementia, after Alzheimer's disease and vascular disease." Hershey (2019) says, "DLB is the third most common of all the neurodegenerative diseases behind both Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease". Tsamakis & Mueller (2021) say that DLB is the "second most common form of neurodegenerative dementia", and Armstrong (2021) says that "Lewy body dementia is the second-most common degenerative dementia after Alzheimer's disease (AD), but DLB is only one part of this diagnostic umbrella."

References

- ^ McKeith et al. 2017, Table 1, p. 90.

- ^ "Lewy body dementia: Hope through research". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. US National Institutes of Health. January 10, 2020. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Hershey & Coleman-Jackson 2019, p. 309.

- ^ "Dementia with Lewy bodies information page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. March 27, 2019. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Gomperts 2016, p. 437.

- ^ Watts et al. 2022, p. 206.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2020, sec. "Sleep disturbances".

- ^ Armstrong 2021, sec. "Progression".

- ^ Levin et al. 2016, p. 62.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2020, sec. "Neuropsychiatric symptoms".

- Weil et al. 2017, Abstract.

- Taylor et al. 2020, Abstract.

- Levin et al. 2016, p. 61.

- Goedert, Jakes & Spillantini 2017, p. S56.

- ^ Armstrong 2021, sec. "Vocabulary".

- Menšíková et al. 2022, Abstract and sec. "Conclusions".

- Armstrong 2019, p. 128.

- ^ Boot 2015, Abstract.

- ^ "What is Lewy body dementia?". National Institute on Aging. US National Institutes of Health. June 27, 2018. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ Kosaka 2017, Orimo S, Chapter 9, pp. 111–112.

- ^ McKeith et al. 2020, p. 743.

- ^ Armstrong 2021, sec. "Prodromal DLB".

- ^ Donaghy, O'Brien & Thomas 2015, pp. 264–265.

- McKeith et al. 2020, p. 745.

- ^ McKeith et al. 2017, sec. "Summary of changes", pp. 88–92.

- St Louis & Boeve 2017, p. 1727.

- Matar et al. 2020, sec. "Introduction".

- ^ O'Dowd et al. 2019, sec. "Prevalence and natural history".

- ^ Matar et al. 2020, sec. "Semiology of cognitive fluctuations".

- ^ Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, p. 4.

- O'Dowd et al. 2019, sec. "Prevalence and natural history", citing McKeith, 2002.

- Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Hershey & Coleman-Jackson 2019, p. 310.

- Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, pp. 1, 3.

- Karantzoulis & Galvin 2011, p. 1584.

- ^ Weil et al. 2017, Table 1.

- Hershey & Coleman-Jackson 2019, p. 314.

- Diamond 2013.

- ^ Gomperts 2016, p. 436.

- ^ Tousi 2017, sec. "Introduction".

- St Louis & Boeve 2017, p. 1724.

- ^ St Louis, Boeve & Boeve 2017, p. 651.

- St Louis, Boeve & Boeve 2017, pp. 645, 651.

- ^ Boot 2015, sec. "Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder".

- ^ St Louis & Boeve 2017, p. 1729.

- Arnaldi et al. 2017, p. 87.

- Armstrong 2019, p. 133.

- Arnaldi et al. 2017, p. 92.

- ^ Walker et al. 2015, p. 1690.

- ^ St Louis, Boeve & Boeve 2017, p. 647.

- ^ Gomperts 2016, p. 438.

- ^ St Louis & Boeve 2017, p. 1728.

- ^ St Louis, Boeve & Boeve 2017, p. 646.

- Aminoff, Greenberg & Simon 2005, pp. 241–245.

- ^ Ogawa et al. 2018, pp. 145–155.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2020, sec. "Motor symptoms".

- ^ Gomperts 2016, p. 447.

- Tousi 2017, sec. "Parkinsonism".

- Hansen et al. 2019, p. 635.

- Burghaus et al. 2012, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Hershey & Coleman-Jackson 2019, p. 313.

- Burghaus et al. 2012, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Pezzoli et al. 2017, sec. "Introduction".

- ^ Tousi 2017, sec. "Hallucinations and delusions".

- ^ McKeith et al. 2017, sec. "Clinical management", pp. 93–95.

- ^ Walker et al. 2015, p. 1685.

- ^ Boot 2015, sec. "Hallucinations and delusions".

- Palma & Kaufmann 2018, pp. 373–377.

- Palma & Kaufmann 2018, p. 381.

- ^ Palma & Kaufmann 2018, p. 382.

- ^ Palma & Kaufmann 2018, p. 384.

- ^ Tousi 2017, Figure 1.

- ^ Walker et al. 2015, p. 1686.

- ^ Palma & Kaufmann 2018, pp. 373–374.

- Kosaka 2017, Yamada M, Chapter 12, p. 157.

- Palma & Kaufmann 2018, p. 373.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2020, sec. "Autonomic dysfunction".

- ^ Palma & Kaufmann 2018, pp. 378–382.

- Zweig & Galvin 2014.

- ^ Palma & Kaufmann 2018, p. 378.

- Palma & Kaufmann 2018, pp. 382–384.

- Karantzoulis & Galvin 2011, p. 1585.

- ^ Tousi 2017, sec. "Anxiety and depression".

- ^ Boot 2015, sec. "Agitation and behavioral disturbances".

- ^ Burghaus et al. 2012, p. 153.

- ^ Walker et al. 2015, p. 1692.

- ^ Walker et al. 2015, p. 1684.

- ^ Linard et al. 2022, p. 1.

- ^ Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, p. 290.

- Arnaldi et al. 2017, p. 89.

- Linard et al. 2022, pp. 1, 9.

- ^ Weil et al. 2017, sec. "Genetics".

- Hansen et al. 2019, p. 637.

- Berge et al. 2014, pp. 1227–1231.

- Hansen et al. 2019, p. 645.

- Arnaldi et al. 2017, p. 82.

- Kosaka 2017, College L, Chapter 11, pp. 141–142.

- Gomperts 2016, p. 449.

- Kosaka 2017, Taylor JP, Chapter 13, pp. 23–24.

- Kosaka 2017, Orimo S, Chapter 9, p. 113.

- Hansen et al. 2019, p. 636.

- Siderowf et al. 2018, p. 529.

- ^ Weil et al. 2017, sec. "Introduction".

- Weil et al. 2017, sec. "Not 'prion-like' spread?".

- ^ Hansen et al. 2019, p. 639.

- Siderowf et al. 2018, p. 531.

- ^ Villemagne et al. 2018, pp. 225–236.

- Hershey & Coleman-Jackson 2019, pp. 310–311.

- Hansen et al. 2019, p. 644.

- Goedert & Spillantini 2017.

- Burghaus et al. 2012, p. 149.

- Walker et al. 2015, pp. 1684–1687.

- Yamada et al. 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Tousi 2017, Abstract.

- Bentley et al. 2021, sec. 4.1, p. 4639; sec. "Discussion", p. 4641.

- ^ Armstrong 2021, sec. "Diagnosis".

- ^ Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, p. 2.

- McKeith et al. 2017, sec. "Pathology", p. 95.

- Armstrong 2021, sec. "Pathology and co-pathology".

- Bentley et al. 2021, sec. 4.1, p. 4639.

- Gomperts 2016, pp. 457–458.

- McKeith et al. 2005, pp. 1863–1872.

- Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, p. 294.

- Chatzikonstantinou S, McKenna J, Karantali E, Petridis F, Kazis D, Mavroudis I (May 2021). "Electroencephalogram in dementia with Lewy bodies: a systematic review". Aging Clin Exp Res. 33 (5): 1197–1208. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01576-2. PMID 32383032. S2CID 218528476.

- Walker, Stefanis & Attems 2019, pp. 467–474.

- "International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 11th Revision: Chapter 06: Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders". World Health Organization. 2010. Archived from the original on February 28, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Diagnosing dementia". National Institute on Aging. US National Institutes of Health. May 17, 2017. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- Haider & Dulebohn 2018.

- ^ Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, p. 5.

- Kosaka 2017, Mori E, Chapter 6, p. 74.

- Kosaka 2017, Mori E, Chapter 6, pp. 75–76.

- Tousi 2017, sec. "REM sleep behavior disorder".

- McKeith et al. 2020, p. 747.

- Kosaka 2017, Yamada M, Chapter 12, p. 162.

- ^ Chung & Kim 2015, pp. 55–66.

- ^ Bousiges & Blanc 2022, sec. "Abstract".

- "Caregiving briefs: Genetics" (PDF). Lewy Body Dementia Association. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Mueller et al. 2017, p. 392.

- McKeith et al. 2020, p. 749.

- Kosaka 2017, Orimo S, Chapter 9, p. 12.

- "Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia". National Institute of Aging. US National Institutes of Health. December 31, 2017. Archived from the original on April 13, 2018. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Gomperts 2016, pp. 436–437.

- ^ Karantzoulis & Galvin 2011, pp. 1582–1587.

- Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, pp. 292–293.

- Karantzoulis & Galvin 2011, p. 1582.

- Walker et al. 2015, pp. 1686–1687.

- Karantzoulis & Galvin 2011, pp. 1583–1584.

- Siderowf et al. 2018, p. 528.

- Gomperts 2016, p. 444.

- ^ Walker et al. 2015, p. 1683.

- Gomperts 2016, p. 442.

- Gomperts 2016, p. 448.

- ^ Gomperts 2016, pp. 447–448.

- Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, p. 296.

- Yamada et al. 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Armstrong 2021, sec. "Management".

- Abdelnour et al. 2023, sec. "Introduction".

- Hershey & Coleman-Jackson 2019, p. 317.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2020, sec. "Introduction".

- ^ Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, p. 298.

- Taylor et al. 2020, sec. "Conclusions and future directions".

- ^ Lin & Truong 2019, pp. 144–150.

- "The use of antipsychotics ... comes with attendant mortality risks ... and they should be avoided whenever possible, given the increased risk of a serious sensitivity reaction." McKeith et al. 1992, pp. 673–674. As cited in McKeith et al. 2017, sec. "Clinical management", pp. 93–95.

- Boot et al. 2013, p. 746.

- ^ Gomperts 2016, Table 4-6, p. 457. Archived July 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Gomperts 2016, p. 458.

- Boot et al. 2013, p. 749.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2020, sec. "Cognitive impairment".

- ^ Walker et al. 2015, p. 1691.

- Boot 2015, sec. "Cognitive symptoms".

- Boot et al. 2013, p. 756.

- Boot 2015, sec. "Sleep symptoms".

- ^ Tousi & Leverenz 2021, Abstract.

- Watts et al. 2022, p. 207.

- Hershey & Coleman-Jackson 2019, p. 315.

- ^ St Louis & Boeve 2017, p. 1731.

- ^ St Louis, Boeve & Boeve 2017, p. 653.

- Palma & Kaufmann 2018, pp. 375–377.

- ^ Connors et al. 2018, sec. "Discussion".

- Walker et al. 2015, pp. 1692–1693.

- Palma & Kaufmann 2018, pp. 374–375.

- Palma & Kaufmann 2018, p. 375.

- ^ Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, p. 297.

- Boot 2015, sec. "Movement symptoms".

- Bentley et al. 2021, sec. 4.3, p. 4640.

- ^ Vann Jones & O'Brien 2014, sec. "Introduction".

- ^ Mueller et al. 2017, p. 393.

- Boot et al. 2013, p. 748.

- Cheng 2017, p. 64.

- ^ Boot et al. 2013, p. 745.

- "Caregiving brief: Behavioral symptoms" (PDF). Lewy Body Dementia Association. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- Burghaus et al. 2012, p. 156.

- Burghaus et al. 2012, p. 152.

- "Caregiving brief: Medications in Lewy body dementia" (PDF). Lewy Body Dementia Association. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- Boot et al. 2013, p. 759.

- ^ St Louis & Boeve 2017, p. 1730.

- ^ Boot et al. 2013, p. 758.

- ^ "Early stage LBD caregiving". Lewy Body Dementia Association. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Mueller et al. 2017, p. 390.

- Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, pp. 298–300.

- Mueller et al. 2017, pp. 392–393.

- ^ Mueller et al. 2017, p. 391.

- Boot 2015, sec. "Postural hypotension".

- Walker et al. 2015, p. 1687.

- Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, pp. 2–3.

- Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, pp. 1, 4.

- Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, p. 300.

- Tahami Monfared et al. 2019, p. 299.

- ^ Mueller et al. 2017, pp. 393–394.

- Mueller et al. 2019, Abstract.

- Bentley et al. 2021, sec. 4.2, p. 4640.

- Bentley et al. 2021, sec. 4.4, p. 4640.

- ^ Kosaka 2017, p. v.

- Tsamakis & Mueller 2021, p. 1.

- Gomperts 2016, p. 440.

- Kosaka 2017, Asada T, Chapter 2, pp. 11–12.

- Hogan et al. 2016, pp. S83–S95.

- Kosaka 2017, Asada T, Chapter 2, p. 17.

- ^ Chiu et al. 2023, sec. "Abstract" and "Sex differences in clinical and population cohorts".

- Kosaka 2017, Asada T, Chapter 2, p. 16.

- ^ Gomperts 2016, p. 435.

- Kosaka 2014, pp. 301–306.

- Engelhardt 2017, pp. 751–753.

- Lewy 1912, pp. 920–933. As cited in Goedert, Jakes & Spillantini 2017, p. S52.

- Engelhardt & Gomes 2017, pp. 198–201.

- ^ Kosaka 2017, Kosaka K, Chapter 1, p. 4.

- Arnaoutoglou, O'Brien & Underwood 2019, pp. 103–112.

- Kosaka et al. 1976, pp. 221–233.

- Kosaka 2017, McKeith IG, Chapter 5, p. 60.

- Kosaka 2017, McKeith IG, Chapter 5, pp. 60–61.

- Kosaka 2017, McKeith IG, Chapter 5, p. 63.

- McKeith 2006, pp. 417–423.

- ^ Goedert et al. 2013, p. 13.

- Kosaka 2017, McKeith IG, Chapter 5, pp. 64–67.

- McKeith et al. 2017, Abstract, p. 88.

- ^ Gallman 2015.

- ^ Williams 2016.

- ^ Robbins 2016.

- ^ Sahlas 2003, pp. 889–892.

- ^ "LBDA Clarifies Autopsy Report on Comedian, Robin Williams". Lewy Body Dementia Association. November 10, 2014. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- McKeith 2015.

- ^ Velayudhan et al. 2017, p. 68.

- Siderowf et al. 2018, pp. 528–529, 533.