| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Health in Kyrgyzstan" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

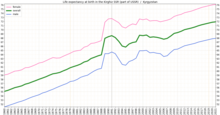

Kyrgyzstan is a lower-middle income country in Central Asia with a population of 6,630,631 in 2022 and a projected increase of 42% by 2050. The life expectancy at birth in 2021 was 71.2 years, an increase of 6.23 years from 66 years in 2000. Healthy life expectancy has also increased, from 58.7 years in 200 to 63.4 years in 2021. In the rest of Kyrgyzstan’s WHO region (Europe), the life expectancy at birth is 76.3 as of 2021, improved from 72.5 years in 2000, and the healthy life expectancy in 2021 is 66, improved from 63.7 years in 2000.

Health system

Kyrgyzstan has a single mandatory health insurance system under the Mandatory Health Insurance Fund (MHIF), which covers a defined package of publicly covered services called the State-Guaranteed Benefits Programme (SGBP) Only 69% of the population was covered by the MHIF in 2019, and many services require co-payments. This is a decline in coverage since 2016, when 76% were covered. Insured patients are fully covered for all primary care services, but the 31% of the population who are not covered, as well as patients who require services outside the SGBP, must pay entirely out-of-pocket.

Decision-making around health policy is primarily within of the Ministry of Health, which is responsible for national health policies, health protection, and health insurance, though external development officers like the WHO have been supporting health system reform. Under the current Healthy Person- Prosperous Country programme of health system reform (2019–2030) the national Public Health Coordinating Council is being revised, with the goal of strengthening the role of local authorities to improve coordination and intersectoral cooperation in implementing successful health programmes.

Most primary, secondary, and tertiary health care providers are public, salaried employees administered by the minister of health at either regional, district, or city level. Some organizations have mixed public-private ownership, like haemodialysis services. Pharmaceuticals are entirely provided by private organizations, though some pharmacies have a contract with the MHIF. The MHIF pools state budget funds, mandatory health insurance contributions, external donor funds and patient co-payments before allocating funds to providers.

Private spending (mostly out-of-pocket payments) accounted for 46.3% of health expenditure in 2019. Almost two thirds of this goes towards medical devices and pharmaceuticals which are either excluded from the SGBP pr require large co-payments. The rest is due to co-payments for inpatient services and a smaller proportion to outpatients and dental services. In terms of social security funding, collection of all funds by the tax authorities is being piloted in two districts, which would replace several smaller social security bodies like The Social Fund.

External development assistance has been declining, from 15.7% in 2004 to 2.3% in 2019. Voluntary health insurance is virtually non-existent.

Health challenges

The biggest cause of death in Kyrgyzstan is cardiovascular disease (CVD). Respiratory diseases and TB (including COVID-19) cause the next highest number of deaths, followed by neoplasms and chronic respiratory diseases.

| Cause | Number of deaths per 100,000 |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | 246.03 |

| Respiratory infections and TB | 142.61 |

| Neoplasms | 125.31 |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 55.94 |

| Diabetes and kidney disease | 40.49 |

When it comes to the biggest burden of disease in Kyrgyzstan, a good measure is disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Looking at DALYs instead of deaths, the impact of maternal and neonatal disorders and musculoskeletal disorders also become more important challenges to address.

| Cause | DALYs per 100,000 |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases | 5,427.81 |

| Respiratory infections and TB | 4,431.18 |

| Neoplasms | 3,209.97 |

| Maternal and neonatal disorders | 2,517.69 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 2,051.33 |

Evaluating risk factors is also important in determining the primary health challenges facing the country. In Kyrgyzstan, the factors that most influence the burden of disease in DALYs are malnutrition, air pollution, and high blood pressure.

Action on health

There have been four major health reforms since Kyrgyzstan's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991: Manas (1996–2005), Manas Taalimi (2006–2011), Den Sooluk (2012-2016, then extended to 2018), and now the current health reform programme is known as Healthy Person - Prosperous Country (2019–2030).

In 2016, WHO reviewed heart attack and stroke services in Kyrgyzstan, and demonstrated that most patents were not diagnosed or treated on time due to fragmentation of clinical pathways and lack of clear implementation of guidelines recommendations, despite CVD being a priority of the health reform system at the time. Based on this evaluation, Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Health established a working group in 2017 to design a service framework and roadmap for the development of CVD care systems under the coordination of the WHO Regional Office for Europe and the WHO Country Office in Kyrgyzstan. Healthy Person - Prosperous Country is aiming for universal health coverage by 2030. To address issues in fragmentation of clinical pathways and lack of effective guideline implementation, the programme incorporates vertical integration of health services and increased public health agency interaction to improve intersections with other sectors, like social services. Various pilots to improve the integration of services are also in process, including for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and mental health care.

UN Sustainable Development Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being

To address health challenges in the country, several strategies are also working in tandem with the Healthy Person - Prosperous Country programme to adapt the global SDG targets related to health and wellbeing to the national context. These include the National Development Strategy for the Kyrgyz Republic 2018-2040 and the Development Programme of the Kyrgyz Republic 2018-2022: Unity. Trust. Creation. The Kyrgyz Government joined the International Health Partnership for UHC based on commitments in implementing the national SDG policy framework. They also signed the United Nations Global Compact in 2018, a great demonstration of commitment to taking action towards universal health coverage.

In 2019, Kyrgyzstan ranked 48 out of 162 countries in the Global SDG Index and Dashboards Report, which ranks countries by an aggregate SDG index of overall performance. In SDG 3, the goal targeting health and wellbeing, 71.6% of targets were achieved in Kyrgyzstan, considered “moderately good progress”. Kyrgyzstan was selected as a pilot country for the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Wellbeing for All (GAP) in the WHO European region, signing a joint statement of partnership to pledge commitment to supporting the national health priorities – in the case of Kyrgyzstan, these priorities are well-articulated in the Health 2030 policy programme. The GAP coordination efforts focused on four priority accelerator areas: - Sustainable financing for health - Primary health care - Determinants of health - Data and digital health To support these priorities, the country-level Development Partner Coordination Council for Health (DPCC) meets on a quarterly basis and is coordinated by WHO. The United National Development System Inter-agencry SDG Work Group also works to support by meeting on a monthly basis to coordinate efforts from United Nations bodies to advance the 2030 agenda and advocate with key stakeholders and government.

Climate and health

Kyrgyzstan is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change in Central Asia. Generally, this is due to its central position in a large continental landmass, the high contribution of weather and climate related activities due to its economy, its very high reliance on water resources for food and energy production, a rugged, steep, and often unproductive topography, and its limited ability to cope with climate change due to limited resource availability.

Economic impact

Kyrgyzstan heavily relies on its glacial meltwater for agriculture and energy, which is a seasonal process in which glaciers and snowfields amass snow and ice throughout the winter, then release it as water into streams, rivers, and lakes as it melts during spring and summer. Hydroelectric power plants generate 90% of the country’s national electrical production. Combined with agriculture, electricity production comprises 20-25% of the GDP, making the country highly dependent on glaciers for its economic health, as well as food and energy security.

Over 60% of the Kyrgyz population lives rurally, with most dependent on natural resources via pastoralism and rainfed and irrigated agriculture. All types of farming are extremely susceptible to climate change due to direct impact of rising temperatures, increases in rainfall variability, intensive agriculture and secondary impacts of higher temperatures on glacial meltwater availability.

Climate change will likely reduce the national budget due to these impacts on Kyrgyzstan's agricultural and energy industries, and therefore also investments in services to protect its population from health impacts of climate change. Public services like schools, health centres, and social support services essential to children’s rights and wellbeing (and health) are already underfunded, especially in areas most at risk from climate threat. The situation is likely to get worse as water/energy resources become scarce and competition for funding increases.

Impact on children

Children are most vulnerable to climate impacts, which include a higher susceptibility to vector-borne diseases, undernutrition, respiratory infections caused by air pollution, physical danger associated with flooding and landslides and a higher risk of abuse, exploitation, trafficking, radicalisation and child labour as climate-related poverty increases. Lifelong impacts of these threats on children include reduced physical and cognitive development and long-term mental and physical health complications and, as a result, lower lifetime earning potential, as well as a greater reliance on functioning public services such as school and hospitals equipped with sufficient electricity for lighting and heating, and water for sanitation.

Air pollution

Air pollution is the biggest environmental risk factor for premature death and ill-health of children and adults in Kyrgyzstan. A 2023 study on the health and social impacts of air pollution on women and children in Bishkek found that air pollution levels in Bishkek were far above those known to have major adverse health effects in urban populations.

Exposure to air pollution prenatally can alter neurological responses and impair cognition throughout life. Children’s lungs are also especially vulnerable to air pollution, and function of the lungs can be permanently altered during fetal or early post-natal life. There is a large burden of disease resulting from exposure to air pollution in children because it leads to acute lower respiratory infections, as well as chronic conditions like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Prenatal exposure to air pollution can also predispose people to cardiovascular disease later in life, and high levels of air pollution could contribute to cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of death in Kyrgyzstan (see table in Health Challenges section).

Action on climate and health

There have been around US$200 million in investments to address climate change since Kyrgyzstan’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. The money came from government, development banks, multilateral and bilateral sources, and primarily targeted agriculture, water management, and natural resource management. However, children have not been targets of specific climate change investments despite being most vulnerable to impacts of climate change.

UNICEF started the Healthy Environments for Healthy Children (HEHC) Global framework in 2021, which includes identifying air pollution as the leading environmental risk for mortality and burden of disease among children. From this, an online course on children’s environmental health is being developed that could assist in training health workers on diseases related to air pollution.

Historical health in Kyrgyzstan as of early 2010s

In the post-Soviet era, Kyrgyzstan's health system has suffered increasing shortages of health professionals and medicine. Kyrgyzstan must import nearly all its pharmaceuticals. The increasing role of private health services has supplemented the deteriorating state-supported system. In the early 2000s, public expenditures on health care decreased as a percentage of total expenditures, and the ratio of population to number of doctors increased substantially, from 296 per doctor in 1996 to 355 per doctor in 2001. A national primary-care health system, the Manas Program, was adopted in 1996 to restructure the Soviet system that Kyrgyzstan inherited. The number of people participating in this program has expanded gradually, and province-level family medicine training centers now retrain medical personnel. A mandatory medical insurance fund was established in 1997.

Largely because of drug shortages, in the late 1990s and early 2000s the incidence of infectious diseases, especially tuberculosis, has increased. The major causes of death are cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. Official estimates of the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have been very low (830 cases were officially reported as of February 2006, but the actual number was estimated at 10 times that many). The concentration of HIV cases in Kyrgyzstan’s drug injecting and prison populations makes an increase in HIV incidence likely. More than half of the cases have been in Osh, which is on a major narcotics trafficking route.

The maternal morality rate rose by more than 15% to 62 deaths per 1000,000 births from 2008 to 2009. According to non-governmental studies, things are worse than the official data indicate.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative finds that Kyrgyzstan is fulfilling 81.2% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to health based on its level of income. When looking at the right to health with respect to children, Kyrgyzstan achieves 98.4% of what is expected based on its current income. In regards to the right to health amongst the adult population, the country achieves only 90.3% of what is expected based on the nation's level of income. Kyrgyzstan falls into the "very bad" category when evaluating the right to reproductive health because the nation is fulfilling only 55.0% of what the nation is expected to achieve based on the resources (income) it has available.

References

- ^ "Health data overview for the Kyrgyz Republic". WHO Data. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Moldoisaeva S, Kaliev M, Sydykova A, Muratalieva E, Ismailov M, Madureira Lima J, Rechel B, Zimmermann, J (2022), Kyrgyzstan: Health System Summary, 2022. WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Copenhagen

- ^ A service framework and roadmap for the development of care systems for heart attack and stroke in Kyrgyzstan. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2018

- ^ "VizHub". GBD Compare. IHME. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Towards a healthier Kyrgyz Republic. Health and sustainable development progress report. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020

- "Kyrgyzstan adopts new health strategy for 2019–2030". WHO Europe. 23 January 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ UNICEF. "Climate Landscape Analysis for Children in Kyrgyzstan: UNICEF Working Paper, 2017" (PDF). UNICEF Kyrgyzstan.

- ^ UNICEF. "Climate Change & Resilience". UNICEF Kyrgyzstan. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ UNICEF. "Health and Social Impacts of Air Pollution on Women and Children in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan". Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ UNICEF. "Exposure of children to PM2.5 air pollution in Bishkek" (PDF). Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Kyrgyzstan country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (January 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "D+C 2011/7-8 – Focus – Azimova/Abazbekova: Tough labour conditions for Central Asia's female health workers - Development and Cooperation - International Journal". Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- "Kyrgyzstan - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- "Kyrgyzstan - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- "Kyrgyzstan - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- "Kyrgyzstan - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 2022-03-18.