Contrast, in physics and digital imaging, is a quantifiable property used to describe the difference in appearance between elements within a visual field. It is closely linked with the perceived brightness of objects and is typically defined by specific formulas that involve the luminances of the stimuli. For example, contrast can be quantified as ΔL/L near the luminance threshold, known as Weber contrast, or as LH/LL at much higher luminances. Further, contrast can result from differences in chromaticity, which are specified by colorimetric characteristics such as the color difference ΔE in the CIE 1976 UCS (Uniform Colour Space).

Understanding contrast is crucial in fields such as imaging and display technologies, where it significantly affects the quality of visual content rendering. The contrast of electronic visual displays is influenced by the type of signal driving mechanism used, which can be either analog or digital. This mechanism directly influences how well the display renders images under varying conditions. Additionally, the contrast is affected by ambient illumination and the viewer's direction of observation, which can alter perceived brightness and color accuracy.

Luminance contrast

The "luminance contrast" is the ratio between the higher luminance, LH, and the lower luminance, LL, that define the feature to be detected. This ratio, often called contrast ratio, CR, (actually being a luminance ratio), is often used for high luminances and for specification of the contrast of electronic visual display devices. The luminance contrast (ratio), CR, is a dimensionless number, often indicated by adding ":1" to the value of the quotient (e.g. CR = 900:1).

with 1 ≤ CR ≤

A "contrast ratio" of CR = 1 means no contrast.

The contrast can also be specified by the contrast modulation (or Michelson contrast), CM, defined as:

with 0 ≤ CM ≤ 1.

CM = 0 means no contrast.

Another contrast definition is a practical application of Weber contrast, sometimes found in the electronic displays field, K or CW, is:

with 0 ≤ CW ≤ 1.

CW = 0 means no contrast, while maximum contrast, CWmax equals one, or more commonly described as a percentage like Michelson, 100%.

A modification of Weber by Hwaung/Peli adds a glare offset to the denominator to more accurately model computer displays. Thus the modified Weber is:

This more accurately models the loss of contrast that occurs on darker display luminance due to ambient light conditions.

Color contrast

Two parts of a visual field can be of equal luminance, but their color (chromaticity) is different. Such a color contrast can be described by a distance in a suitable chromaticity system (e.g. CIE 1976 UCS, CIELAB, CIELUV).

A metric for color contrast often used in the electronic displays field is the color difference ΔE*uv or ΔE*ab.

Full-screen contrast

During measurement of the luminance values used for evaluation of the contrast, the active area of the display screen is often completely set to one of the optical states for which the contrast is to be determined, e.g. completely white (R=G=B=100%) and completely black (R=G=B=0%) and the luminance is measured one after the other (time sequential).

This way of proceeding is suitable only when the display device does not exhibit loading effects, which means that the luminance of the test pattern is varying with the size of the test pattern. Such loading effects can be found in CRT-displays and in PDPs. A small test pattern (e.g. 4% window pattern) displayed on these devices can have significantly higher luminance than the corresponding full-screen pattern because the supply current may be limited by special electronic circuits.

Full-swing contrast

Any two test patterns that are not completely identical can be used to evaluate a contrast between them. When one test pattern comprises the completely bright state (full-white, R=G=B=100%) and the other one the completely dark state (full-black, R=G=B=0%) the resulting contrast is called full-swing contrast. This contrast is the highest (maximum) contrast the display can achieve. If no test pattern is specified in a data sheet together with a contrast statement, it will most probably refer to the full-swing contrast.

Static contrast

The standard procedure for contrast evaluation is as follows:

- Apply the first test pattern to the electrical interface of the display under test and wait until the optical response has settled to a stable steady state,

- Measure the luminance and/or the chromaticity of the first test pattern and record the result,

- Apply the second test pattern to the electrical interface of the display under test and wait until the optical response has settled to a stable steady state,

- Measure the luminance and/or the chromaticity of the second test pattern and record the result,

- Calculate the resulting static contrast for the two test patterns using one of the metrics listed above (CR,CM or K).

When luminance and/or chromaticity are measured before the optical response has settled to a stable steady state, some kind of transient contrast has been measured instead of the static contrast.

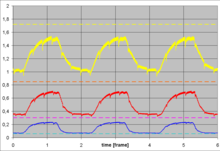

Transient contrast

When the image content is changing rapidly, e.g. during the display of video or movie content, the optical state of the display may not reach the intended stable steady state because of slow response and thus the apparent contrast is reduced if compared to the static contrast.

Dynamic contrast

This is a technique for expanding the contrast of LCD-screens.

LCD-screens comprise a backlight unit which is permanently emitting light and an LCD-panel in front of it which modulates transmission of light with respect to intensity and chromaticity. In order to increase the contrast of such LCD-screens the backlight can be (globally) dimmed when the image to be displayed is dark (i.e. not comprising high intensity image data) while the image data is numerically corrected and adapted to the reduced backlight intensity. In such a way the dark regions in dark images can be improved and the contrast between subsequent frames can be substantially increased. Also the contrast within one frame can be expanded intentionally depending on the histogram of the image (some sporadic highlights in an image may be cut or suppressed). There is quite some digital signal processing required for implementation of the dynamic contrast control technique in a way that is pleasing to the human visual system (e.g. no flicker effects must be induced).

The contrast within individual frames (simultaneous contrast) can be increased when the backlight can be locally dimmed. This can be achieved with backlight units that are realized with arrays of LEDs. High-dynamic-range (HDR) LCDs are using that technique in order to realize (static) contrast values in the range of CR > 100.000.

Dark-room contrast

In order to measure the highest contrast possible, the dark state of the display under test must not be corrupted by light from the surroundings, since even small increments ΔL in the denominator of the ratio (LH + ΔL) / (LL + ΔL) effect a considerable reduction of that quotient. This is the reason why most contrast ratios used for advertising purposes are measured under dark-room conditions (illuminance EDR ≤ 1 lx).

All emissive electronic displays (e.g. CRTs, PDPs) theoretically do not emit light in the black state (R=G=B=0%) and thus, under darkroom conditions with no ambient light reflected from the display surface into the light measuring device, the luminance of the black state is zero and thus the contrast becomes infinity.

When these display-screens are used outside a completely dark room, e.g. in the living room (illuminance approx. 100 lx) or in an office situation (illuminance 300 lx minimum), ambient light is reflected from the display surface, adding to the luminance of the dark state and thus reducing the contrast considerably.

A quite novel TV-screen realized with OLED technology is specified with a dark-room contrast ratio CR = 1.000.000 (one million). In a realistic application situation with 100 lx illuminance the contrast ratio goes down to ~350, with 300 lx it is reduced to ~120.

"Ambient contrast"

The contrast that can be experienced or measured in the presence of ambient illumination is shortly called "ambient contrast". A special kind of "ambient contrast" is the contrast under outdoor illumination conditions when the illuminance can be very intense (up to 100.000 lx). The contrast apparent under such conditions is called "daylight contrast".

Since always the dark areas of a display are corrupted by reflected light, reasonable "ambient contrast" values can only be maintained when the display is provided with efficient measures to reduce reflections by anti reflection and/or anti-glare coatings.

Concurrent contrast

When a test pattern is displayed that contains areas with different luminance and/or chromaticity (e.g. a checkerboard pattern), and an observer sees the different areas simultaneously, the apparent contrast is called concurrent contrast (the term simultaneous contrast is already taken for a different effect). Contrast values obtained from two subsequently displayed full-screen patterns may be different from the values evaluated from a checkerboard pattern with the same optical states. That discrepancy may be due to non-ideal properties of the display-screen (e.g. crosstalk, halation, etc.) and/or due to straylight problems in the light measuring device.

Successive contrast

When a contrast is established between two optical states that are perceived or measured one after the other, this contrast is called successive contrast. The contrast between two full-screen patterns (full-screen contrast) always is a successive contrast.

Methods of measurement

- contrast of direct-view displays

- contrast of projection displays

Depending on the nature of the display under test (direct-view or projection) the contrast is evaluated as a quotient of luminance values (direct-view) or as a quotient of illuminance values (projection displays) if the properties of the projection screen is separated from that of the projector. In the latter case, a checkerboard pattern with full-white and full-black rectangles is projected and the illuminance is measured at the center of the rectangles. The standard ANSI IT7.215-1992 defines test-patterns and measurement locations, and a way to obtain the luminous flux from illuminance measurements, it does not define however a quantity named "ANSI lumen".

If the reflective properties of the projection screen (usually depending on direction) are included in the measurement, the luminance reflected from the centers of the rectangles has to be measured for a (set of) specific directions of observation.

Luminance, contrast and chromaticity of LCD-screens is usually varying with the direction of observation (i.e. viewing direction). The variation of electro-optical characteristics with viewing direction can be measured sequentially by mechanical scanning of the viewing cone (gonioscopic approach) or by simultaneous measurements based on conoscopy.

See also

References

- "Weber and contrast ratios". poynton.ca. Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- IEC(50)845-02-47

- "Luminance Contrast".

- Hwang, Alex D; Peli, Eli (14 February 2016). "Positive and negative polarity contrast sensitivity measuring app". Electronic Imaging. 2016 (16): 1–6. doi:10.2352/ISSN.2470-1173.2016.16.HVEI-122. PMC 5481843. PMID 28649669.

- Shiga, T.; Mikoshiba, S. (2003). "49.2: Reduction of LCTV Backlight Power and Enhancement of Gray Scale Capability by Using an Adaptive Dimming Technique". SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers. 34 (1): 1364. doi:10.1889/1.1832539. S2CID 62588415.

- Chen, Hanfeng; Sung, Junho; Ha, Taehyeun; Park, Yungjun (2007). "Locally pixel-compensated backlight dimming on LED-backlit LCD TV". Journal of the Society for Information Display. 15 (12): 981. doi:10.1889/1.2825108. S2CID 62621574.

- Seetzen, Helge; Whitehead, Lorne A.; Ward, Greg (2003). "54.2: A High Dynamic Range Display Using Low and High Resolution Modulators". SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers. 34 (1): 1450. doi:10.1889/1.1832558. S2CID 15359222.

- STOP Specsmanship

- E. F. Kelley: "Diffuse Reflectance and Ambient Contrast Measurements Using a Sampling Sphere", SID ADEAC06 Digest, pp. 1-5

- Kelley, Edward F.; Lindfors, Max; Penczek, John (2006). "Display daylight ambient contrast measurement methods and daylight readability". Journal of the Society for Information Display. 14 (11): 1019. doi:10.1889/1.2393026. S2CID 61094696.

- ANSI IT7.215-1992: Data Projection Equipment and Large Screen Data Displays -- Test Methods and Performance Characteristics

- M. E. Becker: "Viewing-cone Analysis of LCDs: a Comparison of Measuring Methods", Proc. SID'96, pp. 199

External links

- Charles Poynton: Reducing eyestrain from video and computer monitors

- Contrast of Sonys XEL-1 OLED-TV-screen with ambient illumination

| Display technology | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video displays |

| ||||||

| Non-video | |||||||

| 3D display | |||||||

| Static media | |||||||

| Display capabilities | |||||||

| Related articles | |||||||

| Comparison of display technology | |||||||

with 1 ≤ CR ≤

with 1 ≤ CR ≤

with 0 ≤ CM ≤ 1.

with 0 ≤ CM ≤ 1.

with 0 ≤ CW ≤ 1.

with 0 ≤ CW ≤ 1.