An Amber alert (alternatively styled AMBER alert) or a child abduction emergency alert (SAME code: CAE) is a message distributed by a child abduction alert system to ask the public for help in finding abducted children. The system originated in the United States.

The Amber alert was created in reference to Amber Rene Hagerman, who was abducted and later found murdered on January 17, 1996. Alternative regional alert names were once used; in Georgia, "Levi's Call" (in memory of Levi Frady); in Hawaii, "Maile Amber Alert" (in memory of Maile Gilbert); in Arkansas, "Morgan Nick Amber Alert" (in memory of Morgan Nick); in Utah, "Rachael Alert" (in memory of Rachael Runyan); and in Idaho, "Monkey's Law" (in memory of Michael “Monkey” Joseph Vaughan).

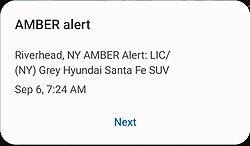

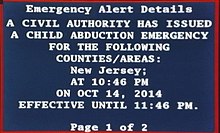

In the United States, the alerts are distributed via commercial and public radio stations, Internet radio, satellite radio, television stations, text messages, and cable TV by the Emergency Alert System and NOAA Weather Radio (where they are termed "Amber Alerts"). The alerts are also issued via e-mail, electronic traffic-condition signs, commercial electronic billboards, or through wireless device SMS text messages.

The US Justice Department's Amber Alert Program has also teamed up with Google and Facebook to relay information regarding an Amber alert to an ever-growing demographic: Amber alerts are automatically displayed if citizens search or use map features on Google, Yahoo!, Bing, and other search engines. With Google public alert (also called Google Amber Alert in some countries), citizens see an Amber alert if they search for related information in a particular location where a minor has recently been abducted and an alert was issued. This is a component of the Amber alert system that is already active in the US (there are also developments in Europe). Those interested in subscribing to receive Amber alerts in their area via SMS messages can visit Wireless Amber alerts, which are offered by law as free messages. In some states, the display scrollboards in front of lottery terminals are also used.

The decision to declare an Amber alert is made by each police organization (in many cases, the state police or highway patrol) investigating the abduction. Public information in an Amber alert usually includes the name and description of the abductee, a description of the suspected abductor, and a description and license plate number of the abductor's vehicle if available.

Activation criteria

The alerts are broadcast using the Emergency Alert System, which had previously been used primarily for weather bulletins, civil emergencies, or national emergencies. In Canada, alerts are broadcast via Alert Ready, a Canadian emergency warning system. Alerts usually contain a description of the child and of the likely abductor. To avoid both false alarms and having alerts ignored as a "wolf cry", the criteria for issuing an alert are rather strict. Each state's or province's Amber alert plan sets its own criteria for activation, meaning that there are differences between alerting agencies as to which incidents are considered to justify the use of the system. However, the U.S. Department of Justice issues the following "guidance", which most states are said to "adhere closely to" (in the U.S.):

- Law enforcement must confirm that an abduction has taken place.

- The child must be at risk of serious injury or death.

- There must be sufficient descriptive information of child, captor, or captor's vehicle to issue an alert.

- The child must be under 18 years of age.

Many law enforcement agencies have not used #2 as a criterion, resulting in many parental abductions triggering an Amber alert, where the child is not known or assumed to be at risk of serious injury or death. In 2013, West Virginia passed Skylar's Law to eliminate #1 as a criterion for triggering an Amber Alert.

It is recommended that Amber alert data immediately be entered into the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) National Crime Information Center. Text information describing the circumstances surrounding the abduction of the child should be entered, and the case flagged as child abduction.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police's (RCMP) requirements in Canada are nearly identical to the above list, with the exception that the RCMP is notified. One organization might notify the other if there is reason to suspect that the border may be crossed.

When investigators believe that a child is in danger of being taken across the border to either Canada or Mexico, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, United States Border Patrol and the Canada Border Services Agency are notified and are expected to search every car coming through a border checkpoint. If the child is suspected to be taken to Canada, a Canadian Amber Alert can also be issued, and a pursuit by Canadian authorities usually follows.

Incidents not meeting alert criteria

For incidents which do not meet Amber alert criteria, the United States Department of Justice developed the Child Abduction Response Teams (CART) program to assist local agencies. This program can be used in all missing children's cases with or without an Amber alert. CART can also be used to help recover runaway children who are under the age of 18 and in danger. As of 2010, 225 response teams have been trained in 43 states, as well as Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, and Canada.

Namesake

| Amber Hagerman | |

|---|---|

Amber Hagerman in December 1995, shortly before her abduction and murder in January 1996 Amber Hagerman in December 1995, shortly before her abduction and murder in January 1996 | |

| Born | Amber Rene Hagerman (1986-11-25)November 25, 1986 Arlington, Texas, U.S. |

| Disappeared | January 13, 1996 |

| Died | January 15, 1996(1996-01-15) (aged 9) Arlington, Texas, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Multiple knife wounds to throat |

| Body discovered | January 17, 1996 |

| Parent(s) | Donna Williams, Richard Hagerman |

Amber Rene Hagerman (November 25, 1986 – January 15, 1996) was a nine-year-old girl abducted while riding her bike in Arlington, Texas. Her younger brother, Ricky, had gone home without her because Amber had wanted to stay in the parking lot for a while. When he returned with his grandfather, they only found her bicycle. A neighbor who had witnessed the abduction called 911.

On hearing the news, Hagerman's father, Richard, called Marc Klaas, whose daughter, Polly, had been kidnapped and murdered in Petaluma, California, in 1993 and Amber's mother, Donna Whitson (now Donna Williams), called the news media and the FBI. They and their neighbors began searching for Amber.

Four days after her abduction, near midnight, a man walking his dog discovered Amber's naked body in a creek behind an apartment complex with severe laceration wounds to her neck. The site of the discovery was less than five miles (8 km) from where she was abducted. Her murder remains unsolved.

Texas program development

Within days of Amber's death, Donna Williams was "calling for tougher laws governing kidnappers and sex offenders". Amber's parents soon established People Against Sex Offenders (PASO). They collected signatures hoping to force the Texas Legislature into passing more stringent laws to protect children.

God's Place International Church donated the first office space for the organization, and as the search for Amber's killer continued, PASO received almost-daily coverage in local media. Companies donated various office supplies, including computer and Internet service. Congressman Martin Frost, with the help of Marc Klaas, drafted the Amber Hagerman Child Protection Act. Both of Hagerman's parents were present when President Bill Clinton signed the bill into law, creating the national sex offender registry. Williams and Richard Hagerman then began collecting signatures in Texas, which they planned to present to then-Governor George W. Bush as a sign that people wanted more stringent laws for sex offenders.

In July 1996, Bruce Seybert (whose own daughter was a close friend of Amber) and Richard Hagerman attended a media symposium in Arlington. Although Hagerman had remarks prepared, on the day of the event the organizers asked Seybert to speak instead. In his 20-minute speech, he spoke about efforts that local police could take quickly to help find missing children and how the media could facilitate those efforts. C.J. Wheeler, a reporter from radio station KRLD, approached the Dallas police chief shortly afterward with Seybert's ideas and launched the first ever Amber Alert.

Williams testified in front of the U.S. Congress in June 1996, asking legislators to create a nationwide registry of sex offenders. Representative Martin Frost, the Congressman who represents Williams' district, proposed an "Amber Hagerman Child Protection Act." Among the sections of the bill was one that would create a national sex offender registry.

Diana Simone, a Texas resident who had been following the news, contacted the KDMX radio station and proposed broadcasts to engage passers-by in helping locate missing children. Her idea was picked up and for the next two years, alerts were made manually to participating radio stations. In 1998, the Child Alert Foundation created the first fully automated Alert Notification System (ANS) to notify surrounding communities when a child was reported missing or abducted. Alerts were sent to radio stations as originally requested but included television stations, surrounding law enforcement agencies, newspapers and local support organizations. These alerts were sent all at once via pagers, faxes, emails, and cell phones with the information immediately posted on the Internet for the general public to view.

Following the automation of the Amber alert with ANS technology created by the Child Alert Foundation, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) expanded its role in 2002 to promote the Amber alert.

International adoption

United States

In October 2000, the United States House of Representatives adopted H.Res.605, which encouraged communities nationwide to implement the AMBER Plan. In October 2001, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children that had declined to be a part of the Amber alert program in February 1996, launched a campaign to have Amber alert systems established nationwide. In February 2002, the Federal Communications Commission officially endorsed the system. In 2002, several children were abducted in cases that drew national attention. One such case, the kidnapping and murder of Samantha Runnion, prompted California to establish an Amber alert system on July 24, 2002. According to Senator Dianne Feinstein, in its first month California issued 13 Amber alerts; 12 of the children were recovered safely and the remaining alert was found to be a misunderstanding.

By September 2002, 26 states had established Amber alert systems that covered all or parts of the state. A bipartisan group of US Senators, led by Kay Bailey Hutchison and Dianne Feinstein, proposed legislation to name an Amber alert coordinator in the U.S. Justice Department who could help coordinate state efforts. The bill also provided $25 million in federal matching grants for states to establish Amber alert programs and necessary equipment purchases, such as electronic highway signs. A similar bill was sponsored in the U.S. House of Representatives by Jennifer Dunn and Martin Frost. The bill passed the Senate unanimously within a week of its proposal. At an October 2002 conference on missing, exploited, and runaway children, President George W. Bush announced changes to the AMBER Alert system, including the development of a national standard for issuing AMBER Alerts. A similar bill passed the House several weeks later on a 390–24 vote. A related bill finally became law in April 2003.

The alerts were offered digitally beginning in November 2002, when America Online began a service allowing people to sign up to receive notification via computer, pager, or cell phone. Users of the service enter their ZIP Code, thus allowing the alerts to be targeted to specific geographic regions.

By 2005, all fifty states had operational programs and today the program operates across state and jurisdictional boundaries. As of January 1, 2013, AMBER Alerts are automatically sent through the Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) program.

Canada

Canada's system began in December 2002, when Alberta launched the first province-wide system. At the time, Alberta Solicitor-General Heather Forsyth said "We anticipate an Amber Alert will only be issued once a year in Alberta. We hope we never have to use it, but if a child is abducted Amber Alert is another tool police can use to find them and help them bring the child home safely." The Alberta government committed to spending more than CA$1 million to expanding the province's emergency warning system so that it could be used effectively for Amber Alerts. Other provinces soon adopted the system, and by May 2004, Saskatchewan was the only province that had not established an Amber Alert system. Within the next year, the program was in use throughout the country.

Amber alerts may also be distributed via the Alert Ready emergency alert system, which disrupts programming on all radio, television stations, and television providers in the relevant region to display and play audio of Amber alert information. In 2018, Alert Ready introduced alerts on supported mobile devices. When an alert is broadcast, a distinct sound is played and a link to find more information is displayed onscreen. Currently, there is no way to deactivate Amber alerts on mobile devices in Canada, even if the device is in silent and/or Do Not Disturb modes, which has provoked controversy. These series of multiple blaring alarms going off in the middle of the night have caused residents to complain, often by calling 911. However, there are concerns that hearing repeated alarms may cause Canadians to ignore the alarm when the system is used to warn of life-threatening emergencies.

British Columbia

Translink, the corporation responsible for the regional transportation network of Metro Vancouver in British Columbia, Canada, displays Amber alerts on all their buses' digital signs reading "AMBER ALERT | Listen to radio | Bus #". Details of the Amber alert information are also available on screens at transit stations.

Quebec

The program was introduced in Quebec on May 26, 2003. The name AMBER alert was then adapted in French to Alerte Médiatique But Enfant Recherché, which directly translates as "Media Alert Goal of Child Recovery". In order to launch an AMBER alert, police authorities need to meet four criteria simultaneously and with no exceptions:

- The missing person is a child under the age of 18.

- The police have reason to believe that the missing child has been abducted.

- The police have reason to believe that the physical safety or the life of the child is in serious danger.

- The police have information that may help locate the child, the suspect and/or the suspect's vehicle.

Once all four conditions are met, the police service may call an AMBER alert. Simultaneously, all of Quebec's Ministry of transport message boards will broadcast the police's messages. The Société de l'assurance automobile du Québec (SAAQ) road traffic controllers also help with the search. Television and radio stations broadcast a description of the child, the abductor and/or the abductor's car. On the radio, the information is broadcast every 20 minutes for two hours or less if the child is found. On the television, the information is broadcast on a ticker tape at the bottom of the screen for two hours with no interruptions. After this, the ticker tape is withdrawn, but the police continue to inform the public through the usual means of communication.

Over the years, the program gathered more partners in order for the alert to be communicated on different media platforms. As in Ontario, lottery crown corporation Loto-Québec puts to the disposition of the police forces their 8,500 terminals located throughout the province. Some of these terminals are equipped with a screen that faces the customer which makes it one of the largest networks of its kind to operate in Canada. The technology employed enables them to broadcast the message on the entire network in under 10 minutes. In addition, The Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association (CWTA) offers to most Canadians, upon free subscription, the possibility to receive, via text message, on their mobile devices AMBER alert notices.

Ontario

Ontario furthered its reach beyond media and highway signs by offering Amber alerts on the province's 9,000 lottery terminal screens.

After the abduction and murder of Victoria Stafford, an online petition was started by Suzie Pereira, a single mother of 2 children who gathered over 61,000 signatures, prompting a review of the Amber Alert. There was some concern regarding the strict criteria for issuing the alerts – criteria that were not met in the Stafford case – that resulted in an alert not being issued. Ontario Provincial Police have since changed their rules for issuing an alert from having to confirm an abduction and confirm threat of harm, to believe that a child has been abducted and believe is at risk of harm.

Mexico

Mexico joined international efforts to spread the use of the Amber alert at an official launch ceremony on April 28, 2011.

Australia

The Australian state of Queensland implemented a version of the Amber alerts in May 2005. Other Australian states joined Queensland in Facebook's Amber Alert program in June 2017.

Europe

AMBER Alert Europe is a foundation that strives to improve the protection of missing children by empowering children and raising awareness on the issue of missing children and its root causes. AMBER Alert Europe advocates that one missing child is one too many and aims for zero missing children in Europe.

AMBER Alert Europe is a neutral platform for the exchange of knowledge, expertise, and best practices on the issue of missing children and its roots causes. To contribute to a safer environment for children, it connects experts from 44 non-governmental and governmental organisations, as well as business entities from 28 countries across Europe.

Its activities cover prevention and awareness-raising, training, research, and child alerting, as well as launching initiatives aimed at impacting policies and legislation in the area of children’s rights. All activities are implemented in line with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and with respect for the privacy of children and data protection laws.

Its beginnings

As a response to missing children cases exceeding geographical borders, the AMBER Alert Europe Foundation was founded in 2013 to contribute to better cross-border coordination and cooperation in the search for missing children.

Since then, its network has expanded and now encompasses different experts from a variety of backgrounds who make their know-how and experiences available to improve existing practices and procedures for a fast and safe recovery of children gone missing. Its joint efforts with police experts in the field of missing children even paved the way for a European police expert network in this area.

With the objective to prevent children from going missing, it also develop activities in the area of prevention, awareness-raising, research, and training together with its network of experts.

France

In February 2006, France's Justice ministry launched an apparatus based on the AMBER alerts named Alerte-Enlèvement (abduction alert) or Dispositif Alerte-Enlèvement (abduction alert apparatus) with the help of most media and railroad and motorway companies.

Netherlands

AMBER Alert Netherlands was launched in 2008. On February 14, 2009, the first Dutch AMBER alert was issued when a 4-year-old boy went missing in Rotterdam. He was found safe and sound after being recognized by a person who saw his picture on an electronic billboard in a fast food restaurant. He was recovered so quickly, that the transmission of the AMBER alert was halted before all recipients received it.

An AMBER alert is issued when a child is missing or abducted and the Dutch police fear that the life or health of the child is in imminent danger. The system enables the police to immediately alert press and public nationwide, by means of electronic highway signs, TV, radio, social media, PCs, large advertising screens (digital signage), email, text messages, apps, RSS news feeds, website banners and pop-ups. There are four key criteria in The Netherlands to be met before an AMBER Alert is issued:

- The child is (very likely) abducted by an unknown person or persons or the child is missing and its life is in imminent danger

- The victim is a minor (under 18 years of age);

- There is enough information about the victim to increase the chances of the child being found by means of an AMBER alert, such as a photo, information about the abductor or the vehicle used during the abduction;

- The AMBER alert is issued as soon as possible after the abduction or disappearance of the child.

In 2021, Dutch police authorities proposed to merge Amber alerts into the Burgernet system. Parliament blocked the initiative. Dutch police continues to send Amber alerts through Burgernet as well as its own social media.

United Kingdom

On April 1, 2007, the AMBER alert system became active in North West England. An implementation across the rest of Britain was planned at that time. This was realized on May 25, 2010, with the nationwide launch of the Child Rescue Alert, based on the AMBER alert system. The first system in the UK of this kind was created in Sussex on November 14, 2002. This was followed by versions in Surrey and Hampshire. By 2005, every local jurisdiction in England and Wales had its own form of alert system. The system was first used in the UK on October 3, 2012, with regard to missing 5 year-old April Jones in Wales.

Ireland

In April 2009, it was announced that an AMBER alert system would be set up in Ireland, In May 2012, the Child Rescue Ireland (CRI) Alert was officially introduced. Ireland's first AMBER alert was issued upon the disappearance of two boys, Eoghan (10) and Ruairí Chada (5).

Serbia

The AMBER alert system, called "Pronađi me" (transl. Find me) started operating in Serbia on October 25, 2023. It was first activated on March 26, 2024 due to the disappearance of two-year-old girl, Danka Ilić, in Banjsko Polje in Bor.

The alerts are distributed via SMS messages and TV programs.

Slovakia

Since April 2015, an emergency child abduction alert system "AMBER Alert Slovakia" is also available in Slovakia. (www.amberalert.sk)

Ukraine

On 22 September 2021, Ukraine's Ministry of Digital Transformation, the National Police of Ukraine and Facebook announced the launch of AMBER alert in Ukraine.

China

On 15 May 2016, the Ministry of Public Security of the People's Republic of China announced the Ministry of Public Security Emergency Release Platform for Children's Missing Information in Beijing, which was soon rolled out to the rest of the country. It is run by the Criminal Investigation Department of the Ministry of Public Security and receives technical support from Alibaba Group. The platform pushes information of missing children confirmed by the police to the mobile phones of the people around the place where the children disappeared, to mobilise people in the area to find and provide feedback on clues related to abductions, trafficking, and related crimes in the area.

Ecuador

In 2018, Ecuador's Department of Security introduced its own Amber alert called Emilia alert, named after the abducted girl Emilia Benavides in December 2017.

Malaysia

In September 2007, Malaysia implemented the Nurin Alert. Based on the Amber alert, it is named for a missing eight-year-old girl, Nurin Jazlin.

Morocco

In March 2023, the General Directorate of National Security of Morocco developed a system in cooperation with Meta Platforms based on the Amber Alert, named "Tifli Moukhtafi" (lit. 'my child is missing'). The alerts are distributed via SMS and on platforms owned by Meta.

Russia

In 2019, Megafon developed its own alert system called MegaFon.Poisk. It is oriented for all regions of Russia where MegaFon is represented and is used for searches of children and adults as well. For less than half of a year, the service has been used for searching of more than 250 people and in more than 30% of situations people called back with information about a lost person.

Retrieval rates

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, of the children abducted and murdered by strangers, 75% are killed within the first three hours of their abduction. Amber alerts are designed to inform the general public quickly when a child has been kidnapped and is in danger so "the public additional eyes and ears of law enforcement". As of December 2023, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children said 1,186 children were recovered because of the Amber alert program.

A Scripps Howard study of the 233 Amber alerts in the United States in 2004 found that most issued alerts did not meet the Department of Justice's criteria. That is, 50% (117 alerts) were categorized as family abductions", e.g., a parent involved in a custody dispute. There were 48 alerts for children who had not been abducted at all, but were lost, ran away, involved in family misunderstandings (for example, two instances where the child was with grandparents), or as the result of hoaxes. Another 23 alerts were issued in cases where police did not know the name of the allegedly abducted child, often as the result of misunderstandings by witnesses who reported an abduction. Seventy of the 233 Amber alerts issued in 2004 (30%) were actually children taken by strangers or who were unlawfully travelling with adults other than their legal guardians.

According to the 2014 Amber Alert Report, 186 Amber alerts were issued in the US, involving 239 children – 60 who were taken by strangers or people other than their legal guardians.

Similar alerts

Some municipalities have used the wireless emergency alert system for categories of people beyond missing children.

In 2012, California created the "silver alert" for missing elderly people, followed by the "feather alert" for missing Indigenous people in 2022, and then the "ebony alert" for missing Black children and young women. Supporters of the ebony alert say that this will dedicate resources to missing Black youths that may not be given sufficient attention through Amber alerts.

Since 2008, Texas has implemented the "blue alert" for suspected cases of serious injury to police officers.

Controversies

Crime control theater

Some outside scholars examining the system in depth disagree with the "official" results. A research team led by criminologist Timothy Griffin reviewed hundreds of abduction cases that occurred between 2003 and 2006 and found that Amber alerts actually had little apparent role in the eventual return of abducted children. The Amber alerts tended to be "successful" in relatively mundane abductions, such as when the child was taken by a noncustodial parent or other family member. There was little evidence that Amber alerts routinely "saved lives", although a crucial research constraint was the impossibility of knowing with certainty what would have happened if no alert had been issued in a particular case.

Griffin and coauthor Monica Miller articulated the limits to Amber alerts in a subsequent research article. They stated that alerts are inherently constrained, because to be successful in the most menacing cases there needs to be a rapid synchronization of several events (rapid discovery that the child is missing and subsequent alert, the fortuitous discovery of the child or abductor by a citizen, and so forth). Furthermore, there is a contradiction between the need for rapid recovery and the prerogative to maintain the strict issuance criteria to reduce the number of frivolous alerts, creating a dilemma for law enforcement officials and public backlash when alerts are not issued in cases ending as tragedies. Finally, the implied causal model of alert (rapid recovery can save lives) is in a sense the opposite of reality: in the worst abduction scenarios, the intentions of the perpetrator usually guarantee that anything public officials do will be "too slow".

Because the system is publicly praised for saving lives despite these limitations, Griffin and Miller argue that Amber alert acts as "crime control theater" in that it "creates the appearance but not the fact of crime control". AMBER Alert is thus a socially constructed "solution" to the rare but intractable crime of child-abduction murder. Griffin and Miller have subsequently applied the concept to other emotional but ineffective legislation such as safe-haven laws and polygamy raids. Griffin considers his findings preliminary, reporting his team examined only a portion of the Amber alerts issued over the three-year period they focused on, so he recommends taking a closer look at the evaluation of the program and its intended purpose, instead of simply promoting the program.

Overuse and desensitization

Advocates for missing children have expressed concerns that the public is gradually becoming desensitized to Amber alerts because of a large number of false or overly broad alarms, where police issue an Amber alert without strictly adhering to the U.S. Department of Justice's activation guidelines.

The timing of a July 2013 New York child abduction alert sent through the Wireless Emergency Alerts system at 4 a.m. raised concerns that many cellphone users would disable WEA alerts.

In 2024, the Texas Department of Public Safety sent a blue alert at 4:50 a.m. to cell phones across the state, some as far as eight hours' drive away from the incident location. The alert prompted thousands of complaints to the Federal Communications Commission, along with public expressions of disbelief that the state government would expect private individuals to wake up in the middle of the night to search for the suspect.

Health effects

A family in Texas claimed their child suffered a ruptured eardrum and inner ear damage, resulting in permanent hearing loss and tinnitus, when an Amber alert was pushed through his earphones at an "ear-shattering volume".

Effects on traffic

Amber alerts are often displayed on electronic message signs. The Federal Highway Administration has instructed states to display alerts on highway signs sparingly, citing safety concerns from distracted drivers and the negative impacts of traffic congestion.

Many states have policies in place that limit the use of Amber alerts on freeway signs. In Los Angeles, an Amber alert issued in October 2002 that was displayed on area freeway signs caused significant traffic congestion. As a result, the California Highway Patrol elected not to display the alerts during rush hour, citing safety concerns. The state of Wisconsin only displays Amber alerts on freeway signs if it is deemed appropriate by the transportation department and a public safety agency. Amber alerts do not preempt messages related to traffic safety.

Influence

The United States Postal Service issued a postage stamp commemorating Amber alerts in May 2006. The 39-cent stamp features a chalk pastel drawing by artist Vivienne Flesher of a reunited mother and child, with the text "AMBER ALERT saves missing children" across the pane. The stamp was released as part of the observance of National Missing Children's Day.

In 2006, a TV movie, Amber's Story, was broadcast on Lifetime. It starred Elisabeth Röhm and Sophie Hough.

A comic book entitled Amber Hagerman Deserves Justice: A Night Owl Story was published by Wham Bang Comics in 2009. Geared toward a young audience by teen author Jake Tinsley and manga artist Jason Dube, it tells Amber's story, recounts the investigation into her murder, and touches on the effect her death has had on young children and parents everywhere. It was created to promote what was then a reopened investigation into her murder.

See also

References

- ^ "About AMBER Alert". AMBER Alert. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- Crawford, Selwyn; Hundley, Wendy (January 23, 2011). "15 Years Later, Critics Debate Effectiveness of Amber Alert". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- "Levi's Call". Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) – Georgia.gov. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- "Maile Amber Alert". Hawaii Department of Attorney General.

- "Morgan Nick Amber Alert". Arkansas State Police. 2006.

- Magazine.noaa.gov Archived October 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "NOAA Weather Radio Leads to Kentucky Amber Alert Success". noaa.gov. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- "Walgreens Electronic Outdoor Signs Now Deliver Vital Weather Messages at More Than 3,000 Corner Locations Across America" (Press release). Walgreens. September 9, 2008. Archived from the original on September 27, 2008.

- Lamaroutdoor.com Archived February 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Glenn, Devon (November 1, 2012). "Google Brings AMBER Alerts for Missing Children to Search and Maps". socialtimes.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014 – via Bing.

- @MissingKids (December 19, 2014). ". @Microsoft } @Bing Announces new @AmberAlert features #ChangeLives http://blogs.bing.com/search/2014/12/18/bing-round-up-amber-alerts-and-new-local-features-for-mobile/" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "OJJDP News @ a Glance – January/February 2011". ncjrs.gov.

- "Wireless AMBER Alerts". Archived from the original on March 5, 2013.

- ^ Irsay, Steve (August 5, 2002), Cold War technology helped save lives of abducted teens, CNN.com, retrieved March 7, 2014

- "What is An AMBER Alert?". missingkids.ca. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- "Amber Alert site restored after online furor over government shutdown". the Guardian. October 7, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- "Guidance on Criteria for Issuing AMBER Alerts" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. April 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 15, 2004.

- "AMBER Alert". Government of Canada Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013.

- "Frequently asked questions OJP" (PDF). 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- Child Abduction: Prevention, Investigation, and Recovery, ISBN 978-0-313-34786-3 p. 112

- The New York Times (January 19, 1996). "Body of Kidnapped Texas Girl Is Found". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- "First Child Saved by Amber Alert Headed to College". May 11, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Pelisek, Christine (January 13, 2022). "Texas Girl's Abduction Inspired the Lifesaving 'Amber Alert,' but 26 Years Later Her Own Case Remains Unsolved". people.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- "Mom says tougher laws needed", Houston Chronicle, January 20, 1996, archived from the original on October 17, 2012, retrieved August 8, 2008

- Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World, Volume 1 ISBN 978-1-412-97685-5 p. 58

- Kopenec, Stefani G. (January 12, 1997), "Young girl's kidnapper elusive: A year has passed without leads on 'low-life killer'", Houston Chronicle, archived from the original on October 20, 2012, retrieved August 8, 2008

- Knight, Paul (April 17, 2009). "Amber Alert: A Trademark Infringement Lawsuit is Not Missing". Houston Press. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Wheeler, C.J. (January 12, 1997), "Mandy's Film and TV Production Directory", Mandy, archived from the original on March 3, 2016, retrieved October 8, 2013,

Launched the first ever Amber Alert in Dallas Texas. Worked closely with the parents of Amber Hagerman and other Texas Radio and TV stations to create a public alert when a child has been abducted. The idea spread nationwide.

- "Parents push for sex offender registry: Family of slain girl fights for new bill", Houston Chronicle, June 20, 1996, archived from the original on October 17, 2012, retrieved August 8, 2008

- Kennedy, Bud (January 14, 2016). "From 2016: 20 years, 794 rescues — how a Hood County woman thought up Amber Alerts". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- Victimology: Theories and Applications ISBN 978-0-763-77210-9 p. 312

- "EveryCRSReport.com: Missing and Exploited Children: Overview and Policy Concerns". Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Lawmakers push national Amber alert system, CNN.com, September 4, 2002, archived from the original on December 11, 2008, retrieved August 8, 2008

- "Nationwide Amber Alert Bill Approved". CBS News. Associated Press. September 10, 2002.

- Bumiller, Elizabeth (October 3, 2002), "Bush Unveils Upgrade of Amber Alert System", The New York Times, archived from the original on February 3, 2009, retrieved August 8, 2008

- House Passes Amber Alert Measure, FoxNews.com, October 8, 2002, archived from the original on February 2, 2009, retrieved August 8, 2002

- "Public Law 108 – 21 – Prosecutorial Remedies and Other Tools to end the Exploitation of Children Today Act of 2003 or PROTECT Act". gpo.gov.

- Mainelli, Tom (November 21, 2002), "AOL Puts AMBER Alert Service Online", PC World, archived from the original on January 30, 2009, retrieved August 8, 2008

- "Frequently asked questions" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- "Amber Alert – WEI Information". Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ "Alberta launches 'Amber Alert' kidnap system". CTV.ca. December 3, 2002. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- B.C., N.S. to begin using 'Amber Alert' system, CTV.ca, May 25, 2004, archived from the original on December 21, 2008, retrieved August 8, 2008

- "Matt Gurney: We need a better robot voice for Amber Alerts". National Post. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- "Ontario viewers peeved after Amber Alert interrupts Sunday night TV-watching". CBC News. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- "Don't call 911 to complain about being awakened by Amber Alert: Police". CityNews Toronto.

- "Amber Alert Police Montreal". SVPM.

- Ontario extends Amber Alert to lottery terminals, CTV.com, April 4, 2005, archived from the original on December 21, 2008, retrieved August 8, 2008

- "CityTV.com". Archived from the original on October 29, 2009.

- "CBC.ca". Archived from the original on August 21, 2009.

- "El Universal – – México, en red de alerta para extraviados". eluniversal.com.mx (in Spanish). June 18, 2013.

- "Home". Alerta AMBER México. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- Waters, Jeff (May 13, 2005), Amber Alert, Stateline Queensland, archived from the original on December 21, 2008, retrieved September 6, 2008

- Benny-Morrison, Ava (June 22, 2017). "Australian police and Facebook launch AMBER Alert child abduction system". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "Netherlands – AMBER Alert". missingkids.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015.

- "Amber Alert". politie.nl. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- "Police to stop use of AMBER Alerts in favor of Dutch system Burgernet | NL Times". nltimes.nl. April 3, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2024.

- "MP's say they want Amber Alert system to stay in use | NL Times". nltimes.nl. June 24, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2024.

- "Wat is Burgernet?". www.politie.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved December 23, 2024.

- "Police to Interrupt TV Programmes to Stop Child Abductions". The Evening Standard. April 2, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- "Child Rescue Alert". National Policing Improvement Agency. Archived from the original on January 29, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- "Abducted child alert system begins". independent. May 25, 2012. Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Bodies of boys to be returned home". independent. July 29, 2013.

- Evropa, Radio Slobodna (October 25, 2023). "U Srbiji pušten u rad sistem po uzoru na Amber alert". Radio Slobodna Evropa (in Serbo-Croatian). Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- srbija.gov.rs. "Amber alert activated in Serbia tonight for the first time". www.srbija.gov.rs. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ""Pronađi me" - kako funkcioniše sistem za pronalaženje nestale dece u Srbiji" ["Pronađi me" - how the Serbian system for searching for missing children works]. insajder.net (in Serbian (Latin script)). October 25, 2023. Archived from the original on November 2, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- "Facebook у партнерстві з Нацполіцією та Мінцифрою запускає систему сповіщення для пошуку зниклих дітей в Україні".

- 邢丙银; 曾雅青 (May 15, 2016). "公安部启动儿童失踪信息紧急发布平台,信息精准推送相关人群". 澎湃新闻. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- "Alerte disparition sur le dispositif "TifliMokhtafi" lancé par la DGSN en partenariat avec Meta". Médias24 (in French). March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- "Alerte enfants disparus : la DGSN lance le dispositif "Tifli moukhtafi" en partenariat avec Meta". Médias24 (in French). March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- "Enfants disparus : la DGSN lance le dispositif " Tifli Moukhtafi " en collaboration avec Meta". Le Desk (in French). March 8, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- "Как большие данные помогают в поиске пропавших людей: кейс компании "МегаФон"". Rusbase (in Russian). October 4, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Knickerbocker, Brad (December 31, 2023). "Amber Alerts: How successful have they been in saving abducted kids?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- Hargrove, Thomas (July 17, 2005). "False alarms endangering future of Amber Alert system". Scripps Howard News Service. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- "2014 Amber Alert Report" (PDF).

- "Silver Alert". California Highway Patrol. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- "Feather Alert". California Highway Patrol. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- "California just created the 'Ebony Alert' to find missing Black children". NBC News. October 10, 2023.

- "Ebony Alert". California Highway Patrol. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ Hurst. "FCC gets thousands of complaints over Blue Alert in Texas shooting". CBS News.

- ^ Finnerty. "'I am not Batman:' Early morning blue alert sparks conversation about Texas' emergency alert system". Spectrum News 1.

- Bennett, Drake. "The Amber alert system is more effective as theater than as a way to protect children". The Boston Globe.

- Tom Jacobs (December 15, 2007). "AMBER Alerts Largely Ineffective, Study Shows". Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Griffin, Timothy; Miller, Monica K.; Hoppe, Jeffrey; Rebideaux, Amy; Hammack, Rachel (December 1, 2007). "A Preliminary Examination of AMBER Alert's Effects". Criminal Justice Policy Review. 18 (4): 378–394. doi:10.1177/0887403407302332. S2CID 144706052.

- Griffin, T.; Miller, M. K. (June 1, 2008). "Child Abduction, AMBER Alert, and Crime Control Theater". Criminal Justice Review. 33 (2): 159–176. doi:10.1177/0734016808316778. S2CID 145360725.

- Quintana, Chris (December 1, 2013). "Overuse, false alarms threaten impact of Amber Alert". Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- "Wake-Up Call for New Yorkers as Police Seek Abducted Boy", NY Times

- Meurer. "This public safety alert woke Texans up, and the internet was not happy about it". KSAT.

- Butterfield, Michelle (May 20, 2022). "Texas family sues Apple, claiming loud Amber Alert damaged son's hearing". Global News.

- "Do Amber Alerts Put Drivers in Jeopardy?". Los Angeles Times. October 15, 2002.

- "Traffic Jams Prompt Amber Alert Shut-Off in L.A." Los Angeles Times. October 5, 2002.

- "Amberalertwisconsin.org" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011.

- "U.S. Postal Service issues new stamp promoting social awareness". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009.

- "Amber Alert Stamp" (PDF).

- Lita Beck (April 21, 2009). "Comic Book Hero Takes on Real Life Murder Case". NBCWashington.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

Further reading

- Douglas, John; Olshaker, Mark (1996). Journey Into Darkness: Follow the FBI's Premier Investigative Profiler as He Penetrates the Minds and Motives of the Most Terrifying Serial Killers. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-749-32394-3. OCLC 43140792.

- Murphy, Paul (2011). Guide for Implementing or Enhancing an Endangered Missing Advisory (EMA). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice. ISBN 978-1-437-98383-8.

- Williams, Charles (2005). Faces of the Amber Alert. Bloomington, Indiana: Author House. ISBN 978-1-420-86783-1.

External links

- U.S. government AMBER alert site

- Our Missing Children (Government of Canada)

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on Amber Alert program technology

- AMBER Alert Nederland site, the Dutch Amber alert

- National Center for Missing & Exploited Children

- Crime Library on Amber Hagerman