| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Sauna" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A sauna (/ˈsɔːnə, ˈsaʊnə/, Finnish: [ˈsɑu̯nɑ]) is a room or building designed as a place to experience dry or wet heat sessions, or an establishment with one or more of these facilities. The steam and high heat make the bathers perspire. A thermometer in a sauna is typically used to measure temperature; a hygrometer can be used to measure levels of humidity or steam. Infrared therapy is often referred to as a type of sauna, but according to the Finnish sauna organizations, infrared is not a sauna.

History

Areas such as the rocky Orkney islands of Scotland have many ancient stone structures for normal habitation, some of which incorporate areas for fire and bathing. It is possible some of these structures also incorporated the use of steam in a way similar to the sauna, but this is a matter of speculation. The sites are from the Neolithic age, dating to approximately 4000 B.C.E. Archaeological sites in Greenland and Newfoundland have uncovered structures very similar to traditional Scandinavian farm saunas, some with bathing platforms and "enormous quantities of badly scorched stones".

The traditional Korean sauna, called the hanjeungmak, is a domed structure constructed of stone that was first mentioned in the Sejong Sillok of the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty in the 15th century. Supported by Sejong the Great, the hanjeungmak was touted for its health benefits and used to treat illnesses. In the early 15th century, Buddhist monks maintained hanjeungmak clinics, called hanjeungso, to treat sick poor people; these clinics maintained separate facilities for men and women due to high demand. Korean sauna culture and kiln saunas are still popular today, and Korean saunas are ubiquitous.

Western saunas originated in Finland where the oldest known saunas were made from pits dug in a slope in the ground and primarily used as dwellings in winter. The sauna featured a fireplace where stones were heated to a high temperature. Water was thrown on the hot stones to produce steam and to give a sensation of increased heat. This would raise the apparent temperature so high that people could take off their clothes. The first Finnish saunas were always of a type now called savusauna; "smoke sauna". These differed from present-day saunas in that they were operated by heating a pile of rocks called a kiuas by burning large amounts of wood for about 6 to 8 hours and then letting out the smoke before enjoying the löyly, a Finnish term meaning, collectively, both the steam and the heat of a sauna (same term in Estonian is leili - you can see similarities with Finnish word). A properly heated "savusauna" yields heat for up to 12 hours.

As a result of the Industrial Revolution, the sauna evolved to use a wood-burning metal stove with rocks on top, kiuas, with a chimney. Air temperatures averaged around 75–100 °C (167–212 °F) but sometimes exceeded 110 °C (230 °F) in a traditional Finnish sauna. As the Finns migrated to other areas of the globe, they brought their sauna designs and traditions with them. This led to a further evolution of the sauna, including the electric sauna stove, which was introduced in 1938 by Metos Ltd in Vaasa. Although sauna culture is more or less related to Finnish and Estonian culture, the evolution of the sauna took place around the same time in Finland and Baltic countries; they all have valued the sauna, its customs and traditions until the present day.

The sauna became very popular especially in Scandinavia and the German-speaking regions of Europe after the Second World War. German soldiers had experienced Finnish saunas during their fight against the Soviet Union during the Continuation War, where they fought on the same side. Saunas were so important to Finnish soldiers that they built them not only in mobile tents but even in bunkers. After the war, the German soldiers brought the custom back to Germany and Austria, where it became popular in the second half of the 20th century. The German sauna culture also became popular in neighbouring countries such as Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

Sauna culture has been registered in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity under two entries: "Smoke sauna tradition in Võromaa" in 2014 and "Sauna culture in Finland" in 2020.

Etymology

The word sauna is an ancient Finnish word referring to both the traditional Finnish bath and to the bathhouse itself. In Finnic languages other than Finnish and Estonian, sauna and cognates do not necessarily mean a building or space built for bathing. It can also mean a small cabin or cottage, such as a cabin for a fisherman. The word is the best known Finnicism in many languages.

Modern saunas

The sauna known in the western world today originates from Northern Europe. In Finland, there are built-in saunas in almost every house, including communal saunas in the older apartment buildings; since the 80s, private saunas have often been built into the bathrooms of typical Finnish flats in apartment buildings, sometimes even in student housing. There are also a number of public saunas in Finland, including Rajaportin Sauna, a sauna located in Tampere, that was first established in 1906 by Hermanni and Maria Lahtinen. Helsinki even has a sauna built into one of the gondolas of a ferris wheel, SkyWheel Helsinki. Unlike many other countries, Finnish people usually prefer to be naked instead of wearing a swimsuit, towel, or other kind of clothing.

Under many circumstances, temperatures approaching and exceeding 100 °C (212 °F) would be completely intolerable and possibly fatal to a person exposed to them for long periods of time. Saunas overcome this problem by controlling the humidity. The hottest Finnish saunas have relatively low humidity levels in which steam is generated by pouring water on the hot stones. This allows air temperatures that could evaporate water to be tolerated and even enjoyed for longer periods of time. Steam baths, such as the hammam, where the humidity approaches 100%, will be set to a much lower temperature of around 50 °C (122 °F) to compensate. The "wet heat" would cause scalding if the temperature were set much higher.

In a typical Finnish sauna, the temperature of the air, the room and the benches are above the dew point even when water is thrown on the hot stones and vaporized. Thus, they remain dry. In contrast, the sauna bathers are at about 60–80 °C (140–176 °F), which is below the dew point, so that water is condensed on the bathers' skin. This process releases heat and makes the steam feel hot.

Finer control over the perceived temperature can be achieved by choosing a higher-level bench for those wishing for a hotter experience, or a lower-level bench for a more moderate temperature. A good sauna has a relatively small temperature gradient between the various seating levels. Doors need to be kept closed and used quickly to maintain the temperature and to keep the steam inside.

Some North American, Western European, Japanese, Russian, and South African public sport center and gyms include sauna facilities. They may also be present at public and private swimming pools. As an additional facility, a sauna may have one or more jacuzzi. In some spa centers, there are the so-called special "snow rooms," also known as cold saunas or cryotherapy. Operating at a temperature of −110 °C (−166 °F), the user is in the sauna for a period of only about 3 minutes.

According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the world's largest sauna is the Koi Sauna in the Thermen & Badewelt Sinsheim, Germany. It measures 166 square meters, holds 150 people and sports a koi aquarium. The title may now belong to Cape East Spa in Haparanda, Sweden, which also holds 150 people but is more spacious. However, in Czeladz, south Poland, there is now a sauna for 300 people, sporting light shows, theatre and needing several sauna masters.

-

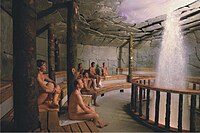

Sauna with geyser at Therme Erding

Sauna with geyser at Therme Erding

-

Modern collective sauna, Erding

Modern collective sauna, Erding

-

Modern sauna in Templin, Germany

Modern sauna in Templin, Germany

-

Modern sauna in Highgrove

Modern sauna in Highgrove

-

A saune on a dock in the Tjuvholmen marina of Oslo, Norway

A saune on a dock in the Tjuvholmen marina of Oslo, Norway

Use

A modern sauna with an electric stove usually takes about 15–30 minutes to heat up. Some users prefer taking a shower beforehand to speed up perspiration in the sauna. When in the sauna, people often sit on a towel for hygiene and put a towel over their heads if the face feels too hot but the body feels comfortable. In Russia, a felt "banya hat" may be worn to shield the head from the heat; this allows the wearer to increase the heat on the rest of the body. The temperature of one's bath can be controlled via:

- the amount of water thrown on the stove: this increases humidity, so that sauna bathers perspire more copiously

- the length of one's stay in the sauna

- positioning: the higher benches are hotter, whereas the lower benches are cooler. Children often sit on the lower benches.

The heat is greatest closest to the stove. Heating from the air is lower on the lower benches as the hot air rises. The heat given by the steam can be very different in different parts of the sauna. As the steam rises directly upwards, it spreads across the roof and travels out towards the corners, where it is then forced downwards. Consequently, the heat of fresh steam may sometimes be felt most strongly in the furthest corners of the sauna. Users increase the duration and the heat gradually over time as they adapt to the sauna. When pouring water onto the stove, it cools down the rocks, but carries more heat into the air via advection, making the sauna warmer.

Perspiration is the result of autonomic responses trying to cool the body. Users are advised to leave the sauna if the heat becomes unbearable, or if they feel faint or ill. Some saunas have a thermostat to adjust the temperature, but the owner of the sauna and the other bathers expect to be consulted before changes are made. The sauna stove and rocks are very hot—one must stay well clear of them to avoid burns, particularly when water is thrown on the rocks, which creates an immediate blast of steam. Combustibles on, or near the stove have been known to cause fires. Contact lenses dry out in the heat. Jewelry or anything metallic, including glasses, will get hot in the sauna and can cause discomfort or burning.

The temperature on different parts of the body can be adjusted by shielding one's body with a towel. Shielding the face with a towel has been found to reduce the perception of heat. Some may wish to put an additional towel or a special cap over the head to avoid dryness. Few people can sit directly in front of the stove without feeling too hot from the radiant heat, but this may not be reflected in their overall body temperature. As the person's body is often the coolest object in a sauna room, steam will condense into water on the skin; this can be confused with perspiration.

Cooling down by immersing oneself in water (in a shower, lake or pool) is a part of the sauna cycle and is as important as the heating. However, it is advisable that healthy people and heart patients alike should take some precautions if plunging into very cold water straight after coming from the hot room, as the rapid cooling of the body produces considerable circulatory stress. It is considered good practice to take a few moments after exiting a sauna before entering a cold plunge, and to enter a plunge pool or a lake by stepping into it gradually, rather than immediately immersing oneself fully. In summer, a session is often started with a cool shower.

In some countries the closest and most convenient access to a sauna is at a gymnasium. Some public pools, major sports centers and resorts also contain a sauna. Therapeutic sauna sessions are often carried out in conjunction with physiotherapy or hydrotherapy; these are gentle exercises that do not exacerbate symptoms.

Health effects

Potential health benefits

There has been widespread research into the health benefits and risks that come from sauna usage; most studies have focused on the Finnish sauna specifically. Sauna bathing leads to mild heat stress, which activates heat shock proteins responsible for repairing misfolded proteins, promoting longevity as well as protection against muscle atrophy and chronic illness.

There is evidence that long-term exposure to Finnish-style sauna is correlated with a reduced risk of sudden cardiac death; and that risk reduction increases with duration and frequency of use; this reduction is more pronounced when sauna bathing is combined with exercise, compared with either of these practices alone. Tentative evidence supports that the heat stress from saunas is associated with reduced blood pressure and arterial stiffness, and therefore also decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease. These benefits are more pronounced in persons with low cardiovascular function. Evidence exists for the benefit of sauna on people with heart failure. Frequent Finnish-style sauna usage (4-7 times per week) is associated with a decreased risk of neurovascular diseases, including Alzheimer's disease and stroke, relative to those individuals who used sauna once per week. Individuals suffering from musculoskeletal disorders could have symptomatic improvement from sauna, and it could be beneficial for glaucoma. It also is associated with a reduced risk and symptom relief from the symptoms of respiratory illness. Weight loss in obese people and improvement of appetite loss present with normal body weight can also be achievable with sauna bathing.

Evidence for the use of sauna for depression or skin disorders is insufficient, but the frequency of sauna sessions is correlated with a diminished risk of developing psychosis, and it might be beneficial for psoriasis.

Potential health risks

Sauna bathing coupled with alcohol consumption or dehydration increases the risk of sudden death; the use of narcotic drugs, such as cocaine, also increases the risk. Being severely obese, having high blood pressure, or being diabetic all serve as reasons to decrease the duration of sauna sessions. Individuals prone to postural hypotension or severe valvular heart disease should use sauna cautiously to reduce the risk of a drop in blood pressure. In people with cardiovascular disease, sauna usage is generally safe, as long as their condition is stable. However, sauna bathing is contraindicated in persons with unstable angina and severe aortic stenosis. A one-year study in Finland showed that only 67 (2.6%) of sudden deaths in saunas were non-accidental, mostly due to coronary heart disease.

Pregnant women can use saunas as long as their core temperature does not exceed 39.0 °C (102.2 °F), as this may be teratogenic.

One study has found that genital heat stress from frequent sauna sessions could cause male infertility.

Technologies

Today there are a wide variety of sauna options. Heat sources include wood, electricity, gas and other more unconventional methods such as solar power. There are wet saunas, dry saunas, infrared saunas, smoke saunas, and steam saunas. There are two main types of stoves: continuous heating and heat storage type. Continuously heating stoves have a small heat capacity and can be heated up on a fast on-demand basis, whereas a heat storage stove has a large heat (stone) capacity and can take much longer to heat.

Heat storage-type

Smoke sauna

Smoke sauna (Finnish savusauna, Estonian suitsusaun, Võro savvusann) is one of the earliest forms of the sauna. It is simply a room containing a pile of rocks, but without a chimney. A fire is lit directly under the rocks and after a while the fire is extinguished. The heat retained in the rocks, and the earlier fire, becomes the main source for heating the sauna. Following this process, the ashes and embers are removed from the hearth, the benches and floor are cleaned, and the room is allowed to air out and freshen for a period of time. The smoke deposits a layer of soot on every surface, so if the benches and back-rests can be removed while the fire is alight the amount of cleaning necessary is reduced. Depending on size of the stove and the airing time, the temperature may be low, about 60 °C (140 °F), while the humidity is relatively high. The tradition almost died out in Finland, but was revived by enthusiasts in the 1980s. These are still used in present-day Finland by some enthusiasts, but usually only on special occasions such as Christmas, New Year's, Easter, and juhannus (Midsummer). Smoke saunas are popular in the southern Estonia and smoke sauna tradition in Võrumaa was added into UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in 2014.

Heat storage-sauna

The smoke-sauna stove is also used with a sealed stone compartment and chimney (a heat storage-stove) which eliminates the smoke odour and eye irritation of the smoke sauna. A heat storage stove does not give up much heat in the sauna before bathing since the stone compartment has an insulated lid. When the sauna bath is started and the löyly shutter opened a soft warmth flow into the otherwise relatively cold (60 °C; 140 °F) sauna. This heat is soft and clean because, thanks to combustion, the stove stones glow red, even white-hot, and are freed of dust at the same time. When bathing the heat-storage sauna will become as hot as a continuous fire-type sauna (80–110 °C; 176–230 °F) but more humid. The stones are usually durable heatproof and heat-retaining peridotite. The upper part of the stove is often insulated with rock wool and firebricks. Heat-storing stoves are also found with electric heating, with similar service but no need to maintain a fire.

Continuous heat-type

Continuous fire sauna

A continuous fire stove, instead of stored heat, is a relatively recent invention. There is a firebox and a smokestack, and stones are placed in a compartment directly above the firebox. It takes a shorter time to heat than the heat-storage sauna, about one hour. A fire-heated sauna requires manual labor in the form of maintaining the fire during bathing; the fire can also be seen as a hazard.

Fire-heated saunas are common in cottages, where the extra work of maintaining the fire is not a problem.

Electric stove sauna

The most common modern sauna types are those with electric stoves. The stones are heated up and kept on temperature using electric heating elements. There is a thermostat and a timer (typically with eight hours' maximum delay time, followed by one hour's continuous heating time) on the stove. This type of heating is generally used only in urban saunas.

Far-infrared saunas

Far-infrared saunas utilize infrared light to generate heat. Unlike traditional saunas that heat the body indirectly through the air or by conduction from heated surfaces, far-infrared saunas use infrared panels or other methods like a sauna blanket that emit far-infrared light, which is absorbed by the surface of the skin. The heat produced by far-infrared saunas is generally lower, making it more tolerable for people who cannot withstand the high temperatures of traditional saunas. Infrared heat penetrates more deeply into fat and the neuromuscular system resulting in a more vigorous sweat at lower temperature than traditional saunas. These effects are favorable for the neuromuscular system to recover from maximal endurance exercise.

Other sweat bathing facilities

Many cultures have sweat baths, though some have more spiritual uses while others are purely secular. In Ancient Rome there was the thermae or balneae (from Greek βαλανεῖον balaneîon), traits of which survive in the Turkish or Arab hammam and in the Victorian Turkish bath (which uses only hot dry air). In the Americas there is the Nahuatl (Aztec) temāzcalli Nahuatl pronunciation: [temaːsˈkalːi], Maya zumpul-ché, and the Mixtec Ñihi; in Canada and the United States, a number of First Nations and Native American cultures have various kinds of spiritual sweat lodges (Lakota: inipi, Anishinaabemowin madoodiswan). In Europe we find the Estonian saun (almost identical to the Finnish sauna), Russian banya, Latvian pirts, the European Jews' shvitz, and the Swedish bastu. In Asia the Japanese Mushi-Buro and the Korean jjimjilbang. The Karo people of Indonesia have the oukup. In some parts of Africa there is the sifutu.

Around the world

Countries that visit the sauna naked are blue, those who wear swim wear are red and those who bring a towel are violet.Although cultures in all corners of the world have imported and adapted the sauna, many of the traditional customs have not survived the journey. Today, public perception of saunas, sauna "etiquette" and sauna customs vary hugely from country to country. In many countries sauna going is a recent fashion and attitudes towards saunas are changing, while in others traditions have survived over generations.

Africa

In Africa, the majority of sauna facilities are found in a more upmarket hotel, spa and health club environments and predominantly share both sauna heater technology and design concepts as applied in Europe. Even though outdoor temperatures remain warmer and more humid, this does not affect the general application or intended sauna experience offered within these commercial environments offering a traditional sauna and or steam shower experience.

Asia

In Iran, most gyms, hotels and almost all public swimming pools have indoor saunas. It is very common for swimming pools to have two saunas which are known in Persian as سونای خشک "dry sauna" and سونای بخار "steam sauna", with the dry type customarily boasting a higher temperature. A cold-water pool (and/or more recently a cold Jacuzzi) is almost always accompanied and towels are usually provided. Adding therapeutic or relaxing essential oils to the rocks is common. In Iran, unlike Finland, sitting in a sauna is mostly seen as part of the spa/club culture, rather than a bathing ritual. It is most usually perceived as a means for relaxation or detoxification (through perspiration). Having a sauna room on private property is considered a luxury rather than a necessity. Public saunas are segregated and nudity is prohibited.

In Japan, many saunas exist at sports centers and public bathhouses (sentō). The saunas are almost always gender separated, often required by law, and nudity is a required part of proper sauna etiquette. While right after World War II, public bathhouses were commonplace in Japan, the number of customers have dwindled as more people were able to afford houses and apartments equipped with their own private baths as the nation became wealthier. As a result, many sentōs have added more features such as saunas in order to survive.

In Korea, saunas are essentially public bathhouses. Various names are used to describe them, such as the smaller mogyoktang, outdoor oncheon, and the elaborate jjimjilbang. The word "sauna" is used a lot for its 'English appeal'; however, it does not strictly refer to the original Fennoscandian steam rooms that have become popular throughout the world. The konglish word sauna (사우나) usually refers to bathhouses with Jacuzzis, hot tubs, showers, steam rooms, and related facilities.

In Laos, herbal steam sauna or hom yaa in Lao, is very popular especially with women and is available in every village. Many women apply yogurt or a paste blend based on tamarind on their skin as a beauty treatment. The sauna is always heated by wood fire and herbs are added either directly to the boiling water or steam jet in the room. The sitting lounge is mix gender but the steam rooms are gender separated. Bael fruit tea known in lao as muktam tea is usually served.

Australia and Canada

In Australia and Canada, saunas are found mainly in hotels, swimming pools, and health clubs and if used by both men and women, nudity is often forbidden, even if implicitly. In gyms or health clubs with separate male and female change rooms, nudity is permitted; however, members are usually asked to shower before using the sauna and to sit on a towel.

In Canada, saunas have increasingly become a fixture of cottage culture, which shares many similarities with its Finnish counterpart (mökki).

Europe

Nordic and Baltic

Finland and Estonia

Main article: Finnish saunaA sauna session can be a social affair in which the participants disrobe and sit or recline in temperatures typically between 70 and 100 °C (158 and 212 °F). This induces relaxation and promotes sweating. People use a bundle of birch twigs with fresh leaves (Finnish: vihta or vasta; Estonian: viht), to slap the skin and create further stimulation of the pores and cells.

The sauna is an important part of daily life, and families bathe together in the home sauna. There are at least 2 million saunas in Finland according to official registers. The Finnish Sauna Society believes the number can actually be as high as 3.2 million saunas (population 5.5 million). Many Finns take at least one a week, and much more when they visit their summer cottage in the countryside. Here the pattern of life tends to revolve around the sauna, and a nearby lake used for cooling off.

-

Rajaportin sauna in Tampere, the oldest working public sauna in Finland

Rajaportin sauna in Tampere, the oldest working public sauna in Finland

-

A modern sauna in Finland

-

A sauna in Estonia

A sauna in Estonia

-

Sauna building in Finland

-

Estonian sauna on a lake

Estonian sauna on a lake

Sauna traditions in Estonia are almost identical to Finland as saunas have traditionally held a central role in the life of an individual. Ancient Estonians believed saunas were inhabited by spirits. In folk tradition sauna was not only the place where one washed but also used as the place where brides were ceremoniously washed, where women gave birth and the place the dying made their final bed. The folk tradition related to the Estonian sauna is mostly identical to that surrounding the Finnish sauna. On New Year's Eve, a sauna would be held before midnight to cleanse the body and spirit for the upcoming year.

Latvia and Lithuania

In Lithuanian, bathhouse or sauna is pirtis; in Latvian, it is pirts. Both countries have long bathhouse traditions, dating back to the pagan times.

The 13th century bathhouses in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were mentioned in the Hypatian Codex and Chronicon terrae Prussiae, as they were practised by the Lithuanian dukes. Livonian Chronicle of Henry describes a bathhouse built around 1196 near the pier on the bank of Daugava river. The chronicle also mentions the year 1215 baths of the Latgalian ruler Tālivaldis which were built in Trikāta. These baths are also mentioned in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle. Sauna had a considerable role in the pagan traditions of the Baltic people. In the 17th century, Matthäus Prätorius described various rituals the Baltic people practiced in sauna. For example, sauna was a primary place for women to give birth and rites would be performed for the Baltic goddess Laima. At that time, sauna traditions were similar in Aukštaitija, Samogitia, Latgale, Semigallia as well as some West Slavic lands. In 1536, Vilnius gained a royal privilege to build public bathhouses and by the end of the 16th century, the city already had 60 of them with a countless number of private ones. In Latvian lands, bathhouses became particularly popular in the 19th century.

The contemporary Baltic sauna is similar to others in the north-eastern part of Europe: it varies according to personal preference, but is typically around 55–70 °C (131–158 °F), humidity 60–90%, with steam being generated by pouring water on the hot stones. Traditionally, birch twigs (Lithuanian: vanta; Latvian: slota) are the most common, but oak or linden are used too. Sauna enthusiasts also make twigs from other trees and plants, including nettle and juniper. Dry air sauna of 80–110 °C (176–230 °F) and very low humidity became popular relatively recently; despite being a misconception, it is sometimes locally described as Finnish-type.

-

Traditional Lithuanian sauna in Zervynos, Dzūkija region

Traditional Lithuanian sauna in Zervynos, Dzūkija region

-

Latvian sauna covered in snow

Latvian sauna covered in snow

-

Lithuanian sauna with the mythological decorations of witches

Lithuanian sauna with the mythological decorations of witches

-

Latvian bathhouse with a pond built in 1862 in Kurzeme, The Ethnographic Open-Air Museum of Latvia

Latvian bathhouse with a pond built in 1862 in Kurzeme, The Ethnographic Open-Air Museum of Latvia

Norway and Sweden

In Norway and Sweden saunas are found in many places, and are known as 'badstu' or 'bastu' (from 'badstuga' "bath cabin, bath house"). In Norway and Sweden, saunas are common in almost every public swimming pool and gym. The public saunas are generally single-sex and may or may not permit use of swimwear. Rules for swimwear and towels for sitting on or covering yourself differ between saunas. Removing body hair in the sauna, staring at other's nudity or spreading odors is considered impolite.

Dutch-speaking regions

Main article: Sauna in the Dutch language areaPublic saunas can be found throughout the Netherlands and Flanders, both in major cities and in smaller municipalities, mixed-sex nudity is the generally accepted rule. Some saunas might offer women-only (or "bathing suit only") times for people who are less comfortable with mixed-sex nudity; Algemeen Dagblad reported in 2008 that women-only, bathing suit-required times are drawing Muslim women in the Netherlands to the sauna.

United Kingdom, Atlantic and Mediterranean Europe

In the United Kingdom and much of Southern Europe, single-gender saunas are the most common type. Nudity is expected in the segregated saunas but usually forbidden in the mixed saunas. Sauna sessions tend to be shorter, and cold showers are shunned by most. In the United Kingdom, where public saunas are becoming increasingly fashionable, the practice of alternating between the sauna and the jacuzzi in short seatings (considered a faux pas in Northern Europe) has emerged.

There is a fast growing new British sauna culture consisting mainly of 'wild' outdoor spas, popping up all over the UK.

In Portugal, the steam baths were commonly used by the Castrejos people, prior to the arrival of the Romans in the western part of the Iberian Peninsula. The historian Strabo spoke of Lusitans traditions that consisted of having steam bath sessions followed by cold water baths. Pedra Formosa is the original name given to the central piece of the steam bath in pre-Roman times.

German-speaking countries

In Germany, Austria, Luxembourg South Tyrol and Lombardy, most public swimming pool complexes have sauna areas; in these locales, nudity is the generally accepted rule, and benches are expected to be covered by people's towels. These rules are strictly enforced in some public saunas. Separate single-sex saunas for both genders are rare, most places offer women-only and mixed-gender saunas, or organize women-only days for the sauna once a week. Loud conversation is not usual as the sauna is seen as a place of healing rather than socializing. Contrary to Russia and Nordic countries, pouring water on hot stones to increase humidity (Aufguss, lit: "Onpouring") is not normally done by the sauna visitors themselves; larger sauna areas have a person in charge (the Saunameister) for that, either an employee of the sauna complex or a volunteer. Aufguss sessions can take up to 10 minutes, and take place according to a schedule. During an Aufguss session, the Saunameister uses a large towel to circulate the hot air through the sauna, intensifying sweating and the perception of heat. Once the Aufguss session has started it is not considered good manners to enter the sauna, as opening the door would cause loss of heat (Sauna guests are expected to enter the sauna just in time before the Aufguss. Leaving the session is allowed, and is advised when feeling too hot or otherwise uncomfortable). Aufguss sessions are usually announced by a schedule on the sauna door. An Aufguss session in progress might be indicated by a light or sign hung above the sauna entrance. Cold showers or baths shortly after a sauna, as well as exposure to fresh air in a special balcony, garden or open-air room (Frischluftraum) are considered a must.

In German-speaking Switzerland, customs are generally the same as in Germany and Austria, although you tend to see more families (parents with their children) and young people. Also in respect to socializing in the sauna the Swiss tend more to be like the Finns, Scandinavians or Russians. Also in German-speaking countries, there are many facilities for washing after using the sauna, with 'dunking pools' (pools of very cold water in which a person dips themselves after using the sauna) or showers. In some saunas and steam rooms, scented salts are given out which can be rubbed into the skin for extra aroma and cleaning effects.

Hungary

Hungarians see the sauna as part of a wider spa culture. Most commonly, mixed genders use the sauna together and wear swimsuits. Single-sex saunas are rare, as well as those which impose nudity although the practice is growing and a number of spas have a towel-only policy on designated days. The most common types of saunas are the very hot and dry Finnish sauna (finn szauna), the steam room (gőzkabin) and the infrared sauna (infraszauna). In many larger spas, you can find a separate sauna section that can only be used with a separate entrance ticket. These units are often called sauna world (szaunavilág) and have additional services, for example a cold plunge pool, resting areas, jacuzzi, showers and crushed ice bucket. Aufguss sessions, led by a qualified sauna master, are becoming popular.

Czech Republic and Slovakia

In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, saunas have a long tradition and are often found as part of recreational facilities, as well as public swimming pools. Many people are regular goers, while many never go. Saunas became more popular after about the year 2000, when large aquaparks and wellness centers began to include them. Nudity is increasingly tolerated, and many places prohibit the use of swimsuits; however, most people cover themselves with a towel. Showers are typically semi-private. Having men and women only days was the norm in the past, but today, men-only facilities are rare, while women-only hours are sometimes provided.

Russia

Main article: Banya (sauna)

In many regions of Russia sauna-going plays a central social role. These countries also have the tradition of massaging fellow sauna-goers with leafy, wet birch bunches, called venik (веник) in Russian. In Russian-speaking communities the word banya (Russian: Баня) is widely used also when referring to a public bath. In Russia, public banya baths are strictly single-sex. During wintertime, sauna-goers often run outdoors for either ice swimming or, in the absence of lake, just to roll around in the snow naked and then go back inside. Russian traditional banya is quite similar to Finnish sauna, despite the popular misconception that the Finnish sauna is very dry.

In modern Russia, there are three different types of saunas. The first one, previously very popular especially during the 20th century, is the public sauna or the banya, (also known as the Russian banya), as it is referred to among the locals, is similar in context to public bathhouses in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The banya is a large setting with many different rooms. There is at least one sauna (Finnish style), one cold pool of water, a relaxation area, another sauna where fellow-sauna goers beat other fellow-sauna goers with the leafy birch, a shower area, a small cafeteria with a TV and drinks, and a large common area that leads to the other areas. In this large area, there are marble bed-like structures where people lie down and receive a massage either by another sauna-member or by a designated masseur. In the resting area, there are also other bed-like structures made of marble or stone attached to the ground where people lie down to rest between different rounds of sauna or at the very end of their banya session. There is also a large public locker area where one keeps one's clothes as well as two other more private locker areas with individual doors that can lock these two separate locker rooms.

The second type of sauna is the Finnish sauna type one can find in any gym throughout the world or a hotel. It could be in the locker room or mixed (i. e. male and female together). Attitudes towards nudity are very liberal and people are less self-conscious about their nude bodies.

The third type of sauna is one that is rented by a group of friends. It is similar to the public banya bath house type, except that it is usually more modern and luxurious, and is often rented by groups of friends by the hour for the use of partying and socialising. Here it can be single-sex or mixed-sex.

North America and Central America

In the United States, the earliest saunas that arrived with the colonists were Swedish bastus in the colony New Sweden around the Delaware River. The Swedish governor at the time had a bathhouse on Tinicum Island. Today sauna culture enjoys its greatest popularity in the Lake Superior Region, specifically the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, especially the Keweenaw Peninsula, and parts of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa, which are home to large populations of Swedish and particularly Finnish Americans. Duluth, Minnesota, at its peak, had as many as 14 public saunas. Indeed, among Finnish farms in Great Lakes "sauna country", the cultural geographer Matti Kaups, found that 90% had sauna structures - more even than the farms in Finland. Elsewhere, sauna facilities are normally provided at health clubs and at hotels, but there is no tradition or ritual to their use. To avoid liability, many saunas operate at only moderate temperatures and do not allow pouring water on the rocks. A wider range of sauna etiquette is usually acceptable in the United States compared to other countries, with the exception that most mixed-sex saunas usually require some clothing such as a bathing suit to be worn. These are uncommon, however, as most saunas are either small private rooms or in the changing rooms of health clubs or gyms. There are few restrictions and their use is casual; bathers may enter and exit the sauna as they please, be it nude, with a towel, dripping wet in swimsuits or even in workout clothes (the latter being very unusual). Like many aspects of US culture, there are few prescribed conventions and the bather should remain astute to "read" the specific family or community's expectations. Besides the Finnish Americans, the older generation of Korean-Americans still uses the saunas as it is available to them. Sauna societies are beginning to emerge in colleges across America, with the first one being formed at Gustavus Adolphus College.

A cultural legacy of Eastern European Jews in America is the culture of 'shvitz', which used to be widespread in the East Coast and occasionally in the Pacific West Coast.

The sweat lodge, used by a number of Native American and First Nations traditional ceremonial cultures, is a location for a spiritual ceremony. The focus is on the ceremony, and the sweating is only secondary. Unlike sauna traditions, and most forcefully in the case of the Inipi, the sweat lodge ceremonies have been robustly defended as an exclusively Native expression of spirituality rather than a recreational activity.

Traditions and old beliefs

A Finnish word löyly is strictly connected to the sauna. It can be translated as "sauna steam" and refers to the steam vapour created by splashing water on the heated rocks. In many languages related to Finnish, there is a word corresponding to löyly. The same approximate meaning is used across the Finnic languages such as in Estonian leil. Originally this word meant "spirit" or "life", as in e. g. Hungarian lélek and Khanty lil, which both mean "soul", referring to the sauna's old, spiritual essence. The same dual meaning of both "spirit" and "(sauna) steam" is also preserved in the Latvian word gars. There is an old Finnish saying, "saunassa ollaan kuin kirkossa",—one should behave in the sauna as in church.

Saunatonttu, literally translated as "sauna elf", is a little gnome or tutelary spirit that was believed to live in the sauna. He was always treated with respect, otherwise, he might cause much trouble for people. It was customary to warm up the sauna just for the tonttu every now and then, or to leave some food outside for him. It is said that he warned the people if a fire was threatening the sauna or punished people who behaved improperly in it—for example, slept, or played games, argued, were generally noisy or behaved otherwise immorally there. Such creatures are believed to exist in different cultures. The Russian banya has an entirely corresponding character called a bannik.

In Thailand, women spend hours in a makeshift sauna tent during a month following childbirth. The steam is typically infused with several herbs. It is believed that the sauna helps the new mother's body return to its normal condition more quickly.

See also

- Aræotic

- Balneotherapy

- Bathtub

- Day spa

- Destination spa

- Hot spring

- Mud bath

- Onsen

- Purification Rundown

- Spa town

- Steambath

- Sudatorium

- Svedana

- Taiwanese hot springs

- World Sauna Championships

Notes

- Minna Hannuksela and Samer Ellahham state the opposite, namely that sauna bathing does not affect fertility.

References

- "sauna". Dictionary.com.

- "sauna". The Free Dictionary.

- "Don't Call it Sauna – Sauna Digest". Sauna Digest. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Gillett, Karrie (29 September 2015). "Bronze age 'sauna' unearthed on Orkney". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020.

- ^ Nordskog, M., Hautala, A (2010)The Opposite of Cold-The Northwoods Finnish Sauna Tradition; University of Minnesota Press

- ^ 한영준 (10 May 2016). 조선보다 못한 '한증막 안전'. 세이프타임즈 (in Korean). Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- "Jjimjilbang: a microcosm of Korean leisure culture". The Korea Herald. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- 김용만. 온천. 네이버캐스트 (in Korean). Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- Sang-hun, Choe (26 August 2010). "Kiln Saunas Make a Comeback in South Korea". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- "Helsinkiläinen sauna". Nationaal Archief. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Maki, Albert (20 September 2010). "New Finland Sauna / New Finlandin saunat". New Finland District. Saskatchewan Gen Web. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Aaland, Mikkel (1978). Sweat. Capra Press. ISBN 0-88496-124-9.

- ^ Birt, Hazel Lauttamus (1988). "New Finland Homecoming 1888–1988" (republished online by Saskatchewan Gen Web Julia Adamson). Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "Sauna: Health benefits, risks, and precautions". www.medicalnewstoday.com Medical News Today. 17 June 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2024.

- Metos Ltd (in Finnish)

- ^ Manfred Scheuch: Nackt; Kulturgeschichte eines Tabus im 20. Jahrhundert; Christian Brandstätter Verlag; Wien 2004; ISBN 3-85498-289-5 pages 156ff

- Kast, Günter (18 November 2014). "Saunakultur und Bekleidungsfrage". Faz.net. die Zeit. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ "Smoke sauna tradition in Võrumaa added to UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List" ERR, 27.11.2014

- "Sauna culture in Finland". UNESCO Intangible Heritage. UNESCO. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Häkkinen, Kaisa (2004): Nykysuomen etymologinen sanakirja. WSOY: Helsinki. pp. 1131–1132

- Finland in Figures, Buildings and summer cottages, Statistics Finland, 2011-06-22

- "Rajaportin sauna". rajaportinsauna.fi. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Orange, Richard (17 May 2016). "Finland launches rival to the London Eye – with a sauna cabin". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Holt, Kermit (15 November 1970). "Good Clean Fun: Finland's Steamy Saunas". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- Hermans, Jo (2012). Physics in daily life. EDP Sciences. p. 59. ISBN 9782759807055.

- Zech, Michael (2015). "Sauna, sweat and science - Quantifying the proportion of condensation water versus sweat using a stable water isotope ((2)H/(1)H and (18)O/(16)O) tracer experiment". Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies. 51 (3): 439–447. doi:10.1080/10256016.2015.1057136. PMID 26110629 – via Pub Med.

- "Ready for your -110° spa treatment? - Macleans.ca".

- "Welcome to Cape East Spa".

- (See http://www.palacsaturna.pl/en/)

- ^ "The sauna use" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2008.

- ^ Norros, Mikko (May 2009). "Bare facts of the sauna in Finland". thisisFINLAND.

- Simmons SE, Mündel T, Jones DA (September 2008). "The effects of passive heating and head-cooling on perception of exercise in the heat". Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 104 (2): 281–8. doi:10.1007/s00421-007-0652-z. PMID 18172673. S2CID 9456781.

- Mündel T, Hooper PL, Bunn SJ, Jones DA (2006). "The effects of face cooling on the prolactin response and subjective comfort during moderate passive heating in humans". Exp. Physiol. 91 (6): 1007–14. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2006.034629. PMID 16916892.

- Publishing, Harvard Health. "Sauna Health Benefits: Are saunas healthy or harmful?". Harvard Health. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "The Health Benefits of a Sauna". PoolGuide. 14 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Buguet A (2007). "Sleep under extreme environments: Effects of heat and cold exposure, altitude, hyperbaric pressure and microgravity in space". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 262 (1–2): 145–52. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.040. PMID 17706676. S2CID 26047824.

- Sohr C (March 1983). "". Z Gesamte Inn Med (in German). 38 (6): 207–13. PMID 6603073.

- Kaszubowski U (2007). "". Z Urol Nephrol (in German). 74 (1): 51–6. PMID 7234155.

- Bender T, Nagy G, Barna I, Tefner I, Kádas E, Géher P (2007). "The effect of physical therapy on beta-endorphin levels". Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 100 (4): 371–82. doi:10.1007/s00421-007-0469-9. PMID 17483960. S2CID 9670316.

- ^ L Hannuksela, Minna; Ellahham, Samer (2001). "Benefits and risks of sauna bathing". The American Journal of Medicine. 110 (2): 118–126. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00671-9. PMID 11165553.

- Patrick, Rhonda P; Johnson, Teresa L. (15 October 2021). "Sauna use as a lifestyle practice to extend healthspan". Experimental Gerontology. 154 (3): 489–492. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2021.111509. PMID 111509. S2CID 236921724.

- Hussain, Joy; Cohen, Marc (2018). "Clinical Effects of Regular Dry Sauna Bathing: A Systematic Review". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018: 1–30. doi:10.1155/2018/1857413. ISSN 1741-427X. PMC 5941775. PMID 29849692.

- Patrick, Rhonda P.; Johnson, Teresa L. (2021). "Sauna use as a lifestyle practice to extend healthspan". Experimental Gerontology. 154: 111509. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2021.111509. PMID 34363927. S2CID 236921724.

- ^ Heinonen, Ilkka; Laukkanen, Jari A. (1 May 2018). "Effects of heat and cold on health, with special reference to Finnish sauna bathing". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 314 (5): R629 – R638. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00115.2017. PMID 29351426. S2CID 13960140.

- ^ Laukkanen, Jari A.; Laukkanen, Tanjaniina; Kunutsor, Setor K. (2018). "Cardiovascular and Other Health Benefits of Sauna Bathing: A Review of the Evidence". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 93 (8): 1111–1121. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.04.008. hdl:1983/875f218f-f6a3-46e8-bdbc-ea005e174ab9. PMID 30077204. S2CID 51922575.

- ^ Laukkanen, Jari A.; Kunutsor, Setor K. (2019). "Is sauna bathing protective of sudden cardiac death? A review of the evidence" (PDF). Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. Advances in the Risk Stratification, Prevention, and Treatment of Sudden Cardiac Death. 62 (3): 288–293. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2019.05.001. PMID 31102597. S2CID 158047297.

- Laukkanen, Jari A.; Laukkanen, Tanjaniina; Khan, Hassan; Babar, Maira; Kunutsor, Setor K. (2018). "Combined Effect of Sauna Bathing and Cardiorespiratory Fitness on the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Deaths in Caucasian Men: A Long-term Prospective Cohort Study". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. Update in Vascular Medicine 2018. 60 (6): 635–641. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2018.03.005. hdl:1983/31d2942a-5b17-420b-bd28-b5a35e6a0659. PMID 29551418.

- ^ Pizzey, Faith K.; Smith, Emily C.; Ruediger, Stefanie L.; Keating, Shelley E.; Askew, Christopher D.; Coombes, Jeff S.; Bailey, Tom G. (2021). "The effect of heat therapy on blood pressure and peripheral vascular function: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Experimental Physiology. 106 (6): 1317–1334. doi:10.1113/EP089424. PMID 33866630. S2CID 233298053.

- Li, Zhongyou; Jiang, Wentao; Chen, Yu; Wang, Guanshi; Yan, Fei; Zeng, Tao; Fan, Haidong (2021). "Acute and short-term efficacy of sauna treatment on cardiovascular function: A meta-analysis". European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 20 (2): 96–105. doi:10.1177/1474515120944584. ISSN 1474-5151. PMID 32814462.

- Källström M, Soveri I, Oldgren J, Laukkanen J, Ichiki T, et al. (November 2018). "Effects of sauna bath on heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Clin Cardiol (Meta-analysis). 41 (11): 1491–1501. doi:10.1002/clc.23077. PMC 6489706. PMID 30239008.

- Ye, Winnie N.; Thipse, Madhura; Mahdi, Maleka Ben; Azad, Sharlin; Davies, Ross; Ruel, Marc; Silver, Marc A.; Hakami, Lale; Mesana, Thierry; Leenen, Frans; Mussivand, Tofy (2020). "Can heat therapy help patients with heart failure?". Artificial Organs. 44 (7): 680–692. doi:10.1111/aor.13659. PMID 32017138. S2CID 211025644.

- Conceição, Lino Sergio Rocha; Queiroz, Jessica Gonçalves de; Neto, Mansueto Gomes; Martins-Filho, Paulo Ricardo Saquete; Carvalho, Vitor Oliveira (1 March 2018). "Effect of Waon Therapy in Individuals With Heart Failure: A Systematic Review". Journal of Cardiac Failure. 24 (3): 204–206. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.01.008. PMID 29409954.

- Mozaffarieh, Maneli; Flammer, Josef (2007). "A novel perspective on natural therapeutic approaches in glaucoma therapy". Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs. 12 (2): 195–198. doi:10.1517/14728214.12.2.195. ISSN 1472-8214. PMID 17604496. S2CID 8048638.

- Kauppinen K (1997). "Facts and fables about sauna". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 813 (1): 654–62. Bibcode:1997NYASA.813..654K. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51764.x. PMID 9100952. S2CID 33060245.

- Biro, Sadatoshi; Masuda, Akinori; Kihara, Takashi; Tei, Chuwa (2003). "Clinical Implications of Thermal Therapy in Lifestyle-Related Diseases". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 228 (10): 1245–1249. doi:10.1177/153537020322801023. ISSN 1535-3702. PMID 14610268. S2CID 3115563.

- ^ Press, E (1991). "The Health Hazards of Saunas and Spas and How to Minimize Them". American Journal of Public Health. 81 (8): 1034–1037. doi:10.2105/AJPH.81.8.1034. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 1405706. PMID 1853995.

- Ravanelli, Nicholas; Casasola, William; English, Timothy; Edwards, Kate M.; Jay, Ollie (2019). "Heat stress and fetal risk. Environmental limits for exercise and passive heat stress during pregnancy: a systematic review with best evidence synthesis". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 53 (13): 799–805. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097914. PMID 29496695. S2CID 3643965.

- Leisegang, Kristian; Dutta, Sulagna (2021). "Do lifestyle practices impede male fertility?". Andrologia. 53 (1): e13595. doi:10.1111/and.13595. hdl:10566/5440. ISSN 0303-4569. PMID 32330362. S2CID 216129511.

- Publishing, Sauna Blanket. "The Far-Infared Sauna Blanket". Sauna Blanket. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Beever R (2009). "Far-infrared saunas for treatment of cardiovascular risk factors: summary of published evidence". Canadian Family Physician. 55 (7): 691–696. PMC 2718593. PMID 19602651.

- Mero A, Tornberg J, Mäntykoski M, Puurtinen R (2015). "Effects of far-infrared sauna bathing on recovery from strength and endurance training sessions in men". SpringerPlus. 4: 321. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1093-5. PMC 4493260. PMID 26180741.

- "Lehdistötiedote: Suomalainen saunominen halutaan Unescon kulttuuriperinnön luetteloihin". Sauna (in Finnish). 5 March 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- Bosworth, Mark (October 2013). "Why Finland loves saunas". BBC News.

- Ivar Paulson, The Old Estonian Folk Religion, Indiana University, 1971

- ^ "Latvijas pirts tradīcijas apgūst pirtnieku festivālā" [Latvian bathhouse traditions are learnt in the festival of bathers]. LSM (in Latvian). 14 August 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ "Lietuviškų garinių pirčių senovė" [The antiquity of Lithuanian steam baths]. Baltai (in Lithuanian). 10 January 2010. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Lietuviška ar rusiška pirtis? Ką sako istorija?" [Lithuanian or Russian sauna? What does the history say?]. Bernardinai.lt (in Lithuanian). 13 April 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Batarags, Ričards (2013). Latviskais pirts rituāls [Latvian sauna ritual] (PDF) (in Latvian). Drukātava. ISBN 978-9984-853-78-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ "Pirtis". Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ Latvijas Enciklopēdiskā vārdnīca, Nacionālais Apgāds, 2002

- ^ Prascevičienė, Rasa (22 April 2010). "Visa tiesa apie pirtį ir jos karalienę vantą" [The whole truth about the sauna and its queen the twig]. Delfi (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- Rožāne, Keita (26 June 2022). "Pēršanās gudrības: Kā pirtī pašam stiprināt miesu, vairot skaistumu un relaksēties" [Bathing wisdom: how to strengthen your body in the sauna yourself, increase your beauty and relax]. LSM (in Latvian). Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- Ribbing, Magdalena (18 March 2016). "Bastustil? - DN.SE". DN.SE (in Swedish). Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- Langendoen, Claudia (10 March 2008). "Moslima's ontdekken badkledingsauna". Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch). Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Tapper, James (12 May 2024). "'It lowers inhibition': how saunas are challenging UK pubs as the place to meet". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

Saunas in the UK have until recently been afterthoughts in hotel spas or places where getting steamy had another, seedier connotation. But after Liz Watson and Katie Bracher created a pop-up Finnish-style sauna on Brighton beach using a converted horse box in 2018, a wave of mobile or permanent saunas have appeared, mostly at the seaside or beside lakes. There are more than 100 around the UK and Ireland, according to the British Sauna Society

- Garcia Quintela, Marco (February 2015). "Iron Age Saunas of Northern Portugal: State of the Art and Research Perspectives". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 34 (1): 68.

- "Bei zu heißem Aufguss Sauna lieber verlassen". www.fr.de (in German). 3 February 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- "Moscow's bathhouses: how to enjoy your sauna". Archived from the original on 31 May 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Londoño, Ernesto (17 February 2024). "Sweating Buckets, and Loving It: Minnesotans and Their Saunas". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

Saunas in the state, part of a tradition with roots in the 1800s, have been especially popular since the pandemic as more people seek a communal experience.

- Niemi, Clemens (1921). Americanization of the Finnish People in Houghton County, Michigan. Duluth, Minnesota: The Finnish Daily Publishing Company. p. 39.

- "The Shvitz". IMDb. 22 October 1993.

- Looking Horse, Arvol (16 October 2009), Concerning the deaths in Sedona, Indian Country Today Media Network, LLC

- Mesteth, Wilmer, et al (10 June 1993) "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality." "At the Lakota Summit V, an international gathering of US and Canadian Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nations, about 500 representatives from 40 different tribes and bands of the Lakota unanimously passed a "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality". The following declaration was unanimously passed."

| Nudity | |

|---|---|

| Nakedness and clothing | |

| Nudity and sexuality | |

| Issues in social nudity | |

| Naturism | |

| Nude recreation | |

| By location | |

| Social nudity advocates | |

| Depictions of nudity | |

| See also | |

| Rooms and spaces of a house | |

|---|---|

| Shared rooms | |

| Private rooms | |

| Spaces | |

| Technical, utility and storage |

|

| Great house areas | |

| Other | |

| Architectural elements | |

| Related | |

Definitions from Wiktionary

Definitions from Wiktionary Media from Commons

Media from Commons Travel guides from Wikivoyage

Travel guides from Wikivoyage