| Nine Years' War (Ireland) | |

|---|---|

| Participants |

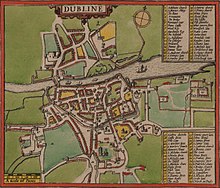

The Dublin gunpowder explosion was a large explosion that took place on the quays of Dublin on 11 March 1597. The explosion demolished as many as forty houses, and left dozens of others badly damaged. The explosion claimed the lives of 126 people and inflicted countless injuries.

The accidental explosion is the worst disaster of the kind to have occurred in Ireland. In the long run, however, the disaster provided the impetus for the expansion of Dublin in the early 17th century and beyond, with the rebuilding efforts laying the foundation of the new city centre.

Explosion of 11 March

In the early afternoon of Friday, 11 March 1597, a consignment of 144 barrels of gunpowder were landed at a place known as 'The Crane' at the northern extremity of Winetavern Street (a building used as the custom house of Dublin prior to the erection of the nearby Custom House in 1707). At the time, ships generally discharged their heavier cargoes at the port of Dalkey, and the remainder at the Crane. The barrels of gunpowder were considered manageable enough to be unloaded by crane from a lighter (a barge) moored at the dock close to Wood Quay.

Shortly after one o'clock, as the wooden crane was shifting four barrels towards the quay, 140 barrels of gunpowder that had been resting on the riverside were engulfed by a massive explosion, transforming the quayside into a scene of devastation. The crane and crane house, which were sited by the barrels, were torn asunder, and the force of the blast was felt far across the city. Nearby, many houses owned by merchant families facing the River Liffey were consumed by the blast, some of them collapsing, others badly defaced. Such was the force of the blast that some buildings in the suburbs of the city were damaged as debris rained down across Dublin. The dozens of riverside labourers who were unlucky enough to be working in the area had no chance of survival: body parts were found scattered hundreds of yards from the crater left by the explosion. In the subsequent investigation, led by 'Michael Chamberlin, Maior (Mayor), and John Shelton and William Pallas, Shrieffs (Sheriffs)', no less than six-score bodies were identified, besides 'sondrie headles bodies and heades without bodies that were found and not knowne.'

The contemporaneous Gaelic chronicle known as the Annals of the Four Masters describes the disaster:

- ...a spark of fire got into the powder; but from whence that spark proceeded, whether from the heavens or from the earth beneath, is not known; howbeit, the barrels burst into one blazing flame and rapid conflagration, which raised into the air, from their solid foundations and supporting posts, the stone mansions and wooden houses of the street, so that the long beam, the enormous stone, and the man in his corporal shape, were sent whirling into the air over the town by the explosion of this powerful powder; and it is impossible to enumerate, reckon, or describe the number of honourable persons, of tradesmen of every class, of women and maidens, and of the sons of gentlemen, who had come from all parts of Ireland to be educated in the city, that were destroyed.

Lead-up to explosion

The disaster took place against the backdrop of the Nine Years' War, in which the Ulster leader Hugh O'Neill and his allies were engaged in an armed challenge to the English Crown. Vast quantities of gunpowder were required to supply the English army in Ireland. The main destination for the cargo of gunpowder was Dublin, the principal city of Ireland. These were offloaded by English ships onto boats waiting offshore: from there, they were ferried across the shallow water to the city.

In the days before the explosion, a dispute had arisen between the Dublin porters and the castle officials. A crown official by the name of John Allen, the clerk of the storehouse, had threatened and intimidated a number of the porters, forcing them to work without pay. As such, many of the porters were effectively on strike, refusing to help unload the barrels of gunpowder. This led to a buildup of gunpowder on the quays. This series of events set into motion the explosion which was to follow.

Exactly what triggered the conflagration of the barrels was never determined, although the day of the explosion was noted as unusually dry.

Aftermath: Dublin rebuilt

The disaster claimed 126 lives, both men and women, and mostly locals. At the time, the population of Dublin was not quite 10,000, so the impact of the death toll was significant, representing about 1⁄80 of the population of the city.

Although the immediate impact of the explosion was horrific, the rebuilding that took place in the early 17th century paved the way for the dramatic expansion of Dublin in the 1600s. In contrast to the timber that was widely employed in Ireland in the medieval and Tudor era, much of the new building was in brick. The rebuilding effort also spilled into newly reclaimed land in the east of the city. This facilitated the dramatic growth of the population of the city, from less than 10,000 in 1600 to around 20,000 by the 1630s.

The rebuilding effort was in some respects comparable to that which took place in London after the Great Fire of 1666, transforming medieval Dublin into a more modern city.

See also

- Cork gunpowder explosion (1810)

References

Notes

- Connolly 2007, p. 282.

- ^ Fitzpatrick 1907.

- Lennon 1995.

- Annals of the Four Masters, p. 2014.

- Connolly 2007, p. 283.

Sources

- Connolly, S. J. (2007). Contested Island: Ireland 1460–1630. Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Annals of the Four Masters" – via UCC Corpus of Electronic Texts.

- Fitzpatrick, Samuel A. Ossory (1907). Dublin. A Historical and Topographical Account of the City. Cork: Tower Books.

- Lennon, Colm (1995). "Dublin's Great Explosion of 1597". History Ireland Magazine. Vol. 3. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

External links

Categories: