| Acronym | DMA |

|---|---|

| Classification | Thermal analysis |

| Other techniques | |

| Related | Isothermal titration calorimetry Dynamic mechanical analysis Thermomechanical analysis Thermogravimetric analysis Differential thermal analysis Dielectric thermal analysis |

Dynamic mechanical analysis (abbreviated DMA) is a technique used to study and characterize materials. It is most useful for studying the viscoelastic behavior of polymers. A sinusoidal stress is applied and the strain in the material is measured, allowing one to determine the complex modulus. The temperature of the sample or the frequency of the stress are often varied, leading to variations in the complex modulus; this approach can be used to locate the glass transition temperature of the material, as well as to identify transitions corresponding to other molecular motions.

Theory

Viscoelastic properties of materials

Polymers composed of long molecular chains have unique viscoelastic properties, which combine the characteristics of elastic solids and Newtonian fluids. The classical theory of elasticity describes the mechanical properties of elastic solids where stress is proportional to strain in small deformations. Such response to stress is independent of strain rate. The classical theory of hydrodynamics describes the properties of viscous fluid, for which stress response depends on strain rate. This solidlike and liquidlike behaviour of polymers can be modelled mechanically with combinations of springs and dashpots, making for both elastic and viscous behaviour of viscoelastic materials such as bitumen.

Dynamic moduli of polymers

The viscoelastic property of a polymer is studied by dynamic mechanical analysis where a sinusoidal force (stress σ) is applied to a material and the resulting displacement (strain) is measured. For a perfectly elastic solid, the resulting strain and the stress will be perfectly in phase. For a purely viscous fluid, there will be a 90 degree phase lag of strain with respect to stress. Viscoelastic polymers have the characteristics in between where some phase lag will occur during DMA tests. When the strain is applied and the stress lags behind, the following equations hold:

- Stress:

- Strain:

where

- is the frequency of strain oscillation,

- is time,

- is phase lag between stress and strain.

Consider the purely elastic case, where stress is proportional to strain given by Young's modulus . We have

Now for the purely viscous case, where stress is proportional to strain rate.

The storage modulus measures the stored energy, representing the elastic portion, and the loss modulus measures the energy dissipated as heat, representing the viscous portion. The tensile storage and loss moduli are defined as follows:

- Storage modulus:

- Loss modulus:

- Phase angle:

Similarly, in the shearing instead of tension case, we also define shear storage and loss moduli, and .

Complex variables can be used to express the moduli and as follows:

where

Derivation of dynamic moduli

Shear stress of a finite element in one direction can be expressed with relaxation modulus and strain rate, integrated over all past times up to the current time . With strain rate and substitution one obtains . Application of the trigonometric addition theorem lead to the expression

with converging integrals, if for , which depend on frequency but not of time. Extension of with trigonometric identity lead to

- .

Comparison of the two equations lead to the definition of and .

Applications

Measuring glass transition temperature

One important application of DMA is measurement of the glass transition temperature of polymers. Amorphous polymers have different glass transition temperatures, above which the material will have rubbery properties instead of glassy behavior and the stiffness of the material will drop dramatically along with a reduction in its viscosity. At the glass transition, the storage modulus decreases dramatically and the loss modulus reaches a maximum. Temperature-sweeping DMA is often used to characterize the glass transition temperature of a material.

Polymer composition

Varying the composition of monomers and cross-linking can add or change the functionality of a polymer that can alter the results obtained from DMA. An example of such changes can be seen by blending ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) with styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) and different cross-linking or curing systems. Nair et al. abbreviate blends as E0S, E20S, etc., where E0S equals the weight percent of EPDM in the blend and S denotes sulfur as the curing agent.

Increasing the amount of SBR in the blend decreased the storage modulus due to intermolecular and intramolecular interactions that can alter the physical state of the polymer. Within the glassy region, EPDM shows the highest storage modulus due to stronger intermolecular interactions (SBR has more steric hindrance that makes it less crystalline). In the rubbery region, SBR shows the highest storage modulus resulting from its ability to resist intermolecular slippage.

When compared to sulfur, the higher storage modulus occurred for blends cured with dicumyl peroxide (DCP) because of the relative strengths of C-C and C-S bonds.

Incorporation of reinforcing fillers into the polymer blends also increases the storage modulus at an expense of limiting the loss tangent peak height.

DMA can also be used to effectively evaluate the miscibility of polymers. The E40S blend had a much broader transition with a shoulder instead of a steep drop-off in a storage modulus plot of varying blend ratios, indicating that there are areas that are not homogeneous.

Instrumentation

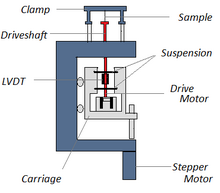

The instrumentation of a DMA consists of a displacement sensor such as a linear variable differential transformer, which measures a change in voltage as a result of the instrument probe moving through a magnetic core, a temperature control system or furnace, a drive motor (a linear motor for probe loading which provides load for the applied force), a drive shaft support and guidance system to act as a guide for the force from the motor to the sample, and sample clamps in order to hold the sample being tested. Depending on what is being measured, samples will be prepared and handled differently. A general schematic of the primary components of a DMA instrument is shown in figure 3.

Types of analyzers

There are two main types of DMA analyzers used currently: forced resonance analyzers and free resonance analyzers. Free resonance analyzers measure the free oscillations of damping of the sample being tested by suspending and swinging the sample. A restriction to free resonance analyzers is that it is limited to rod or rectangular shaped samples, but samples that can be woven/braided are also applicable. Forced resonance analyzers are the more common type of analyzers available in instrumentation today. These types of analyzers force the sample to oscillate at a certain frequency and are reliable for performing a temperature sweep.

Analyzers are made for both stress (force) and strain (displacement) control. In strain control, the probe is displaced and the resulting stress of the sample is measured by implementing a force balance transducer, which utilizes different shafts. The advantages of strain control include a better short time response for materials of low viscosity and experiments of stress relaxation are done with relative ease. In stress control, a set force is applied to the sample and several other experimental conditions (temperature, frequency, or time) can be varied. Stress control is typically less expensive than strain control because only one shaft is needed, but this also makes it harder to use. Some advantages of stress control include the fact that the structure of the sample is less likely to be destroyed and longer relaxation times/ longer creep studies can be done with much more ease. Characterizing low viscous materials come at a disadvantage of short time responses that are limited by inertia. Stress and strain control analyzers give about the same results as long as characterization is within the linear region of the polymer in question. However, stress control lends a more realistic response because polymers have a tendency to resist a load.

Stress and strain can be applied via torsional or axial analyzers. Torsional analyzers are mainly used for liquids or melts but can also be implemented for some solid samples since the force is applied in a twisting motion. The instrument can do creep-recovery, stress–relaxation, and stress–strain experiments. Axial analyzers are used for solid or semisolid materials. It can do flexure, tensile, and compression testing (even shear and liquid specimens if desired). These analyzers can test higher modulus materials than torsional analyzers. The instrument can do thermomechanical analysis (TMA) studies in addition to the experiments that torsional analyzers can do. Figure 4 shows the general difference between the two applications of stress and strain.

Changing sample geometry and fixtures can make stress and strain analyzers virtually indifferent of one another except at the extreme ends of sample phases, i.e. really fluid or rigid materials. Common geometries and fixtures for axial analyzers include three-point and four-point bending, dual and single cantilever, parallel plate and variants, bulk, extension/tensile, and shear plates and sandwiches. Geometries and fixtures for torsional analyzers consist of parallel plates, cone-and-plate, couette, and torsional beam and braid. In order to utilize DMA to characterize materials, the fact that small dimensional changes can also lead to large inaccuracies in certain tests needs to be addressed. Inertia and shear heating can affect the results of either forced or free resonance analyzers, especially in fluid samples.

Test modes

Two major kinds of test modes can be used to probe the viscoelastic properties of polymers: temperature sweep and frequency sweep tests. A third, less commonly studied test mode is dynamic stress–strain testing.

Temperature sweep

A common test method involves measuring the complex modulus at low constant frequency while varying the sample temperature. A prominent peak in appears at the glass transition temperature of the polymer. Secondary transitions can also be observed, which can be attributed to the temperature-dependent activation of a wide variety of chain motions. In semi-crystalline polymers, separate transitions can be observed for the crystalline and amorphous sections. Similarly, multiple transitions are often found in polymer blends.

For instance, blends of polycarbonate and poly(acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene) were studied with the intention of developing a polycarbonate-based material without polycarbonate's tendency towards brittle failure. Temperature-sweeping DMA of the blends showed two strong transitions coincident with the glass transition temperatures of PC and PABS, consistent with the finding that the two polymers were immiscible.

Frequency sweep

A sample can be held to a fixed temperature and can be tested at varying frequency. Peaks in and in E’’ with respect to frequency can be associated with the glass transition, which corresponds to the ability of chains to move past each other. This implies that the glass transition is dependent on strain rate in addition to temperature. Secondary transitions may be observed as well.

The Maxwell model provides a convenient, if not strictly accurate, description of viscoelastic materials. Applying a sinusoidal stress to a Maxwell model gives: where is the Maxwell relaxation time. Thus, a peak in E’’ is observed at the frequency . A real polymer may have several different relaxation times associated with different molecular motions.

Dynamic stress–strain studies

By gradually increasing the amplitude of oscillations, one can perform a dynamic stress–strain measurement. The variation of storage and loss moduli with increasing stress can be used for materials characterization, and to determine the upper bound of the material's linear stress–strain regime.

Combined sweep

Because glass transitions and secondary transitions are seen in both frequency studies and temperature studies, there is interest in multidimensional studies, where temperature sweeps are conducted at a variety of frequencies or frequency sweeps are conducted at a variety of temperatures. This sort of study provides a rich characterization of the material, and can lend information about the nature of the molecular motion responsible for the transition.

For instance, studies of polystyrene (Tg ≈110 °C) have noted a secondary transition near room temperature. Temperature-frequency studies showed that the transition temperature is largely frequency-independent, suggesting that this transition results from a motion of a small number of atoms; it has been suggested that this is the result of the rotation of the phenyl group around the main chain.

See also

- Maxwell material

- Standard linear solid material

- Thermomechanical analysis

- Dielectric thermal analysis

- Time–temperature superposition

- Electroactive polymers

References

- "What is Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)?". 22 April 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- Ferry, J.D. (1980). Viscoelastic properties of polymers (3 ed.). Wiley.

- Ferry, J.D (1991). "Some reflections on the early development of polymer dynamics: Viscoelasticity, dielectric dispersion and self-diffusion". Macromolecules. 24 (19): 5237–5245. Bibcode:1991MaMol..24.5237F. doi:10.1021/ma00019a001.

- ^ Meyers, M.A.; Chawla K.K. (1999). Mechanical Behavior of Materials. Prentice-Hall.

- Ferry, J.D.; Myers, Henry S (1961). Viscoelastic properties of polymers. Vol. 108. The Electrochemical Society.

- ^ Nair, T.M.; Kumaran, M.G.; Unnikrishnan, G.; Pillai, V.B. (2009). "Dynamic Mechanical Analysis of Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Monomer Rubber and Styrene-Butadiene Rubber Blends". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 112: 72–81. doi:10.1002/app.29367.

- "DMA". Archived from the original on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- ^ Menard, Kevin P. (1999). "4". Dynamic Mechanical Analysis: A Practical Introduction. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-8688-8.

- ^ Young, R.J.; P.A. Lovell (1991). Introduction to Polymers (2 ed.). Nelson Thornes.

- J. Màs; et al. (2002). "Dynamic mechanical properties of polycarbonate and acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene copolymer blends". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 83 (7): 1507–1516. doi:10.1002/app.10043.

External links

- Dynamical Mechanical Analysis Retrieved May 21, 2019.

is the frequency of strain oscillation,

is the frequency of strain oscillation, is time,

is time, is phase lag between stress and strain.

is phase lag between stress and strain. . We have

. We have

and

and  .

.

and

and  as follows:

as follows:

of a finite element in one direction can be expressed with relaxation modulus

of a finite element in one direction can be expressed with relaxation modulus  and strain rate, integrated over all past times

and strain rate, integrated over all past times  up to the current time

up to the current time  and substitution

and substitution  one obtains

one obtains  . Application of the trigonometric addition theorem

. Application of the trigonometric addition theorem  lead to the expression

lead to the expression

for

for  , which depend on frequency but not of time. Extension of

, which depend on frequency but not of time. Extension of  with trigonometric identity

with trigonometric identity  lead to

lead to

.

. equations lead to the definition of

equations lead to the definition of  appears at the glass transition temperature of the polymer. Secondary transitions can also be observed, which can be attributed to the temperature-dependent activation of a wide variety of chain motions. In

appears at the glass transition temperature of the polymer. Secondary transitions can also be observed, which can be attributed to the temperature-dependent activation of a wide variety of chain motions. In  where

where  is the Maxwell relaxation time. Thus, a peak in E’’ is observed at the frequency

is the Maxwell relaxation time. Thus, a peak in E’’ is observed at the frequency  . A real polymer may have several different relaxation times associated with different molecular motions.

. A real polymer may have several different relaxation times associated with different molecular motions.