| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Economy of Myanmar" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. Please consider expanding the lead to provide an accessible overview of all important aspects of the article. (March 2024) |

Yangon, the financial center of Myanmar Yangon, the financial center of Myanmar | |

| Currency | Myanmar Kyat (MMK) |

|---|---|

| Fiscal year | 1 October– 30 September |

| Trade organisations | WTO, ASEAN, BIMSTEC, RCEP, G77, AFTA, ADB and others |

| Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

| GDP growth |

|

| All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Myanmar is the seventh largest in Southeast Asia. After the return of civilian rule in 2011, the new government launched large-scale reforms, focused initially on the political system to restore peace and achieve national unity and moving quickly to an economic and social reform program. Current economic statistics were a huge decline from the economic statistics of Myanmar in the fiscal year of 2020, in which Myanmar’s nominal GDP was $81.26 billion and its purchasing power adjusted GDP was $279.14 billion. Myanmar has faced an economic crisis since the 2021 coup d'état. According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) Myanmar GDP per capita in 2024 is est to reach $1.179

History

Classical era

Burma has been the main trade route between China and India since 100 BC. The Mon Kingdom of lower Burma served as important trading centre in the Bay of Bengal. The majority of the population was involved in rice production and other forms of agriculture. Burma used silver as a medium of exchange. All land was technically owned by the Burmese monarch. Exports, along with oil wells, gem mining and teak production were controlled by the monarch. Burma was vitally involved in the Indian Ocean trade. Logged teak was a prized export that was used in European shipbuilding because of its durability, and became the focal point of Burmese exports from the 1700s to the 1800s.

Under the monarchy, the economy of Myanmar had been one of redistribution, a concept embedded in local society, religion, and politics (Dāna). The state set the prices of the most important commodities. Agrarian self-sufficiency was vital, while trade was only of secondary importance.

British Burma (1885–1948)

Further information: British rule in BurmaUnder the British administration, the people of Burma were at the bottom of social hierarchy, with Europeans at the top, Indians, Chinese, and Christianized minorities in the middle, and Buddhist Burmese at the bottom. Integrated into the world economy by force, economic growth in Burma was driven by the extractive industries and cash crop agriculture, and the country had the second-highest GDP per capita in Southeast Asia. However, much of the wealth was concentrated in the hands of Europeans. The country became the world's largest exporter of rice, mainly to European markets, while other colonies like India suffered mass starvation. The British followed the ideologies of Social Darwinism and the free market, and opened up the country to a large-scale immigration with Rangoon exceeding New York City as the greatest immigration port in the world in the 1920s. Historian Thant Myint-U states, "This was out of a total population of only 13 million; it was equivalent to the United Kingdom today taking 2 million people a year." By then, in most of the largest cities in Burma, Rangoon, Akyab, Bassein and Moulmein, the Indian immigrants formed a majority of the population. The Burmese under British rule felt helpless, and reacted with a "racism that combined feelings of superiority and fear".

Crude oil production, an indigenous industry of Yenangyaung, was taken over by the British and put under Burmah Oil monopoly. British Burma began exporting crude oil in 1853. It produced 75% of the world's teak. The wealth was however, mainly concentrated in the hands of Europeans. In the 1930s, agricultural production fell dramatically as international rice prices declined and did not recover for several decades.

During the Japanese invasion of Burma in World War II, the British followed a scorched earth policy. They destroyed the major government buildings, oil wells and mines for tungsten, tin, lead and silver to keep them from the Japanese. Myanmar was bombed extensively by the Allies. After independence, the country was in ruins with its major infrastructure completely destroyed. With the loss of India, Burma lost relevance and obtained independence from the British. After a parliamentary government was formed in 1948, Prime Minister U Nu embarked upon a policy of nationalisation and the state was declared the owner of all land. The government tried to implement an eight-year plan partly financed by injecting money into the economy which caused some inflation.

Post-independence and under U Nu and Ne Win (1948–1988)

After a parliamentary government was formed in 1948, Prime Minister U Nu embarked upon a policy of nationalisation. He attempted to make Burma a welfare state by adopting central planning measures. By the 1950s, rice exports had decreased by two-thirds and mineral exports by over 96%. Plans were implemented in setting up light consumer industries by private sector. The 1962 Burmese coup d'état was followed by an economic scheme called the Burmese Way to Socialism, a plan to nationalise all industries, with the exception of agriculture. The catastrophic program turned Burma into one of the world's most impoverished countries. Burma was classified as a least developed country by the United Nations in 1987.

Rule of the generals (1988–2011)

After 1988, the regime retreated from a command economy. It permitted modest expansion of the private sector, allowed some foreign investment, and received much needed foreign exchange. The economy was rated in 2009 as the least free in Asia (tied with North Korea). All basic market institutions are suppressed. Private enterprises were often co-owned or indirectly owned by state. The corruption watchdog organisation Transparency International in its 2007 Corruption Perceptions Index released on 26 September 2007 ranked Burma the most corrupt country in the world, tied with Somalia.

The national currency is the kyat. Burma currently has a dual exchange rate system similar to Cuba. The market rate was around two hundred times below the government-set rate in 2006. In 2011, the Burmese government enlisted the aid of the International Monetary Fund to evaluate options to reform the current exchange rate system, to stabilise the domestic foreign exchange trading market and reduce economic distortions. The dual exchange rate system allows for the government and state-owned enterprises to divert funds and revenues, while also giving the government more control over the local economy and making it possible to temporarily subdue inflation.

Inflation averaged 30.1% between 2005 and 2007. In April 2007, the National League for Democracy organised a two-day workshop on the economy. The workshop concluded that skyrocketing inflation was impeding economic growth. "Basic commodity prices have increased from 30% to 60% since the military regime promoted a pay rise for government workers in April 2006," said Soe Win, the moderator of the workshop. "Inflation is also correlated with corruption." Myint Thein, an NLD spokesperson, added: "Inflation is the critical source of the current economic crisis."

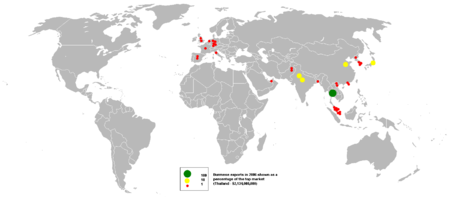

In recent years, China and India attempted to strengthen ties with Myanmar for mutual benefit. The European Union and some nations including the United States and Canada imposed investment and trade sanctions on Burma. The United States banned all imports from Burma, though this restriction was since lifted. Foreign investment comes primarily from China, Singapore, South Korea, India, and Thailand.

Economic liberalisation (2011–2019)

| This section is in list format but may read better as prose. You can help by converting this section, if appropriate. Editing help is available. (March 2024) |

In 2011, when new President Thein Sein's government came to power, Burma embarked on a major policy of reforms including anti-corruption, currency exchange rate regulation, foreign investment laws and taxation. Foreign investments increased from US$300 million in 2009–10 to a US$20 billion in 2010–11 by about 6567%. Large inflow of capital results in stronger Burmese currency, kyat by about 25%. In response, the government relaxed import restrictions and abolished export taxes. Despite current currency problems, Burmese economy is expected to grow by about 8.8% in 2011. After the completion of 58-billion dollar Dawei deep seaport, Burma is expected be at the hub of trade connecting Southeast Asia and the South China Sea, via the Andaman Sea, to the Indian Ocean receiving goods from countries in the Middle East, Europe and Africa, and spurring growth in the ASEAN region.

In 2012, the Asian Development Bank formally began re-engaging with the country, to finance infrastructure and development projects in the country. The $512 million loan is the first issued by the ADB to Myanmar in 30 years and will target banking services, ultimately leading to other major investments in road, energy, irrigation and education projects.

In March 2012, a draft foreign investment law emerged, the first in more than 2 decades. This law oversees the unprecedented liberalisation of the economy. It for example stipulates that foreigners no longer require a local partner to start a business in the country and can legally lease land. The draft law also stipulates that Burmese citizens must constitute at least 25% of the firm's skilled workforce, and with subsequent training, up to 50–75%.

On 28 January 2013, the government of Myanmar announced deals with international lenders to cancel or refinance nearly $6 billion of its debt, almost 60 per cent of what it owes to foreign lenders. Japan wrote off US$3 Billion, nations in the group of Paris Club wrote off US$2.2 Billion and Norway wrote off US$534 Million.

Myanmar's inward foreign direct investment has steadily increased since its reform. The country approved US$4.4 billion worth of investment projects between January and November 2014.

According to one report released on 30 May 2013, by the McKinsey Global Institute, Burma's future looks bright, with its economy expected to quadruple by 2030 if it invests in more high-tech industries. This however does assume that other factors (such as drug trade, the continuing war of the government with specific ethnic groups, etc.) do not interfere.

As of October 2017, less than 10% of Myanmar's population has a bank account. As of 2016–17 approximately 98 percent of the population has smartphones and mobile money schemes are being implemented without the use of banks similar to African countries.

Economic crisis (2020–present)

On April 30, 2021, the United Nations Development Programme published a report indicating that the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état in February 2021 could reverse economic gains made over the last sixteen years. Myanmar's economy has been in economic crisis since the coup d’état in 2021.

Since at least 2022, Myanmar is undergoing an ailing economy; the ruling military junta plans to shore up the worsening state of its balance of payments. When the kyat fell by a third of its pre-coup value, the central bank then sold $600 million worth of foreign reserves (10% of the entire country's total) to prop up the kyat. By April 2022, reserves dwindled, foreign investment fell and remittances plummeted. This led the junta to impose capital controls and import restrictions which led to shortages of diabetes and cancer medicines.

Still unresolved internal problems

In a first ever countrywide study in 2013, the Myanmar government found that 37 per cent of the population were unemployed and 26 per cent lived in poverty.

The current state of the Burmese economy has also had a significant impact on the people of Burma, as economic hardship results in extreme delays of marriage and family building. The average age of marriage in Burma is 27.5 for men, 26.4 for women, almost unparalleled in the region, with the exception of developed countries like Singapore.

Burma also has a low fertility rate of 2.07 children per woman (2010), especially as compared to other Southeast Asian countries of similar economic standing, like Cambodia (3.18) and Laos (4.41), representing a significant decline from 4.7 in 1983, despite the absence of a national population policy. This is at least partly attributed to the economic strain that additional children place on family income, and has resulted in the prevalence of illegal abortions in the country, as well as use of other forms of birth control.

The 2012 foreign investment law draft, included a proposal to transform the Myanmar Investment Commission from a government-appointed body into an independent board. This could bring greater transparency to the process of issuing investment licenses, according to the proposed reforms drafted by experts and senior officials. However, even with this draft, it will still remain a question on whether corruption in the government can be addressed (links have been shown between certain key individuals inside the government and the drug trade, as well as many industries that use forced labour -for example the mining industry-).

Many regions (such as the Golden Triangle) remain off-limits for foreigners, and in some of these regions, the government is at war with the country's ethnic minorities and the opposition.

Industries

The major agricultural product is rice which covers about 60% of the country's total cultivated land area. Rice accounts for 97% of total food grain production by weight. Through collaboration with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), 52 modern rice varieties were released in the country between 1966 and 1997, helping increase national rice production to 14 million tons in 1987 and to 19 million tons in 1996. By 1988, modern varieties were planted on half of the country's rice fields, including 98% of the irrigated areas. In 2011, Myanmar's total milled rice production accounted for 10.60 million tons, an increase from the 1.8 per cent back in 2010.

In northern Burma, opium bans have ended a century old tradition of growing poppy. Between 20,000 and 30,000 ex-poppy farmers left the Kokang region as a result of the ban in 2002.

Rubber plantations are being promoted in areas of high elevation like Mong Mao. Sugar is grown in the lowlands such as Mong Pawk District.

The lack of an educated workforce skilled in modern technology contributes to the country's economic problems.

Lately, the Myanmar lacks adequate infrastructure. Goods travel primarily across Thai and China borders and through the main port in Yangon.

Railroads are old and dilapidated, with few repairs since their construction under British rule in the late nineteenth century. Presently China and Japan are providing aid to upgrade rail transport. Highways are normally paved, except in remote border regions. Energy shortages are common throughout the country including in Yangon. About 30 percent of the country's population does not have access to electricity, with 70 per cent of people living in rural areas. The civilian government has indicated that electricity will be imported from Laos to fulfil demand.

Other industries include agricultural goods, textiles, wood products, construction materials, gems, metals, oil and natural gas.

The private sector dominates agriculture, light industry, and transport activities, while the government controls energy, heavy industry, and military industries.

Garment production

The garment industry is a major job creator in the Yangon area, with around 200,000 workers employed in total in mid-2015. The Myanmar Government has introduced minimum wage of MMK 4,800 (US$3.18) per day for the garment workers from March 2018.

The Myanmar garments sector has seen significant influx of foreign direct investment, if measured by the number of entries rather than their value. In March 2012, six of Thailand's largest garment manufacturers announced that they would move production to Myanmar, principally to the Yangon area, citing lower labour costs. In mid-2015, about 55% of officially registered garment firms in Myanmar were known to be fully or partly foreign-owned, with about 25% of the foreign firms from China and 17% from Hong Kong. Foreign-linked firms supply almost all garment exports, and these have risen rapidly in recent years, especially since EU sanctions were lifted in 2012. Myanmar exported $1.6 billion worth of garments and textiles in 2016.

Illegal drug trade

Further information: Opium production in Burma See also: Golden Triangle (Southeast Asia)

Burma (Myanmar) is the largest producer of methamphetamines in the world, with the majority of ya ba found in Thailand produced in Burma, particularly in the Golden Triangle and Northeastern Shan State, which borders Thailand, Laos and China. Burmese-produced ya ba is typically trafficked to Thailand via Laos, before being transported through the northeastern Thai region of Isan.

In 2010, Burma trafficked 1 billion tablets to neighbouring Thailand. In 2009, the Chinese authorities seized over 40 million tablets that had been illegally trafficked from Burma. Ethnic militias and rebel groups (in particular the United Wa State Army) are responsible for much of this production; however, the Burmese military units are believed to be heavily involved in the trafficking of the drugs.

Burma is also the second largest supplier of opium (following Afghanistan) in the world, with 95% of opium grown in Shan State. Illegal narcotics have generated $1 to US$2 billion in exports annually, with estimates of 40% of the country's foreign exchange coming from drugs. Efforts to eradicate opium cultivation have pushed many ethnic rebel groups, including the United Wa State Army and the Kokang to diversify into methamphetamine production.

Prior to the 1980s, heroin was typically transported from Burma to Thailand, before being trafficked by sea to Hong Kong, which was and still remains the major transit point at which heroin enters the international market. Now, drug trafficking has shifted to southern China (from Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, Guangdong) because of a growing market for drugs in China, before reaching Hong Kong.

The prominence of major drug traffickers have allowed them to penetrate other sectors of the Burmese economy, including the banking, airline, hotel and infrastructure industries. Their investment in infrastructure have allowed them to make more profits, facilitate drug trafficking and money laundering. The share of informal economy in Myanmar is one of the largest in the world that feeds into trade in illegal drugs.

Oil and gas

Main article: Oil and gas industry in Myanmar

- Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE) is the national oil and gas company of Burma. The company is a sole operator of oil and gas exploration and production, as well as domestic gas transmission through a 1,900-kilometre (1,200 mi) onshore pipeline grid.

- The Yadana Project is a project to exploit the Yadana gas field in the Andaman Sea and to carry natural gas to Thailand through Myanmar.

- Sino-Burma pipelines refers to planned oil and natural gas pipelines linking Burma's deep-water port of Kyaukphyu (Sittwe) in the Bay of Bengal with Kunming in Yunnan province, China.

- The Norwegian company Seadrill owned by John Fredriksen is involved in offshore oildrilling, expected to give the Burmese government oil and oil export revenues.

- Myanmar exported $3.5 billion worth of gas, mostly to Thailand in the fiscal year up to March 2012.

- Initiation to bid on oil exploration licenses for 18 of Myanmar's onshore oil blocks has been released on 18 January 2013.

Renewable energy

Myanmar has rich solar power and hydropower potential. The country's technical solar power potential is the greatest among the countries of the Greater Mekong Subregion. Wind energy, biogas and biomass have limited potential and are weakly developed.

Financing geothermal projects in Myanmar use an estimated break even power cost of 5.3–8.6 U.S cents/kWh or in Myanmar Kyat 53–86K per kWh. This pegs a non-fluctuating $1=1000K, which is a main concern for power project funding. The main drawback with depreciation pressures, in the current FX market. Between June 2012 and October 2015, the Myanmar Kyat depreciated by approximately 35%, from 850 down to 1300 against the US Dollar. Local businesses with foreign denominated loans from abroad suddenly found themselves rushing for a strategy to mitigate currency risks. Myanmar's current lack of available currency hedging solutions presents a real challenge for geothermal project financing.

Gemstones

Myanmar's economy depends heavily on sales of precious stones such as sapphires, pearls and jade. Rubies are the biggest earner; 90% of the world's rubies come from the country, whose red stones are prized for their purity and hue. Thailand buys the majority of the country's gems. Burma's "Valley of Rubies", the mountainous Mogok area, 200 km (120 mi) north of Mandalay, is noted for its rare pigeon's blood rubies and blue sapphires. Burma's gemstone industry is a cornerstone of the Burmese economy with exports topping $1 billion.

In 2007, following the crackdown on pro-democracy protests in Myanmar, human rights organisations, gem dealers, and US First Lady Laura Bush called for a boycott of a Myanmar gem auction held twice yearly, arguing that the sale of the stones profited the dictatorial regime in that country. Debbie Stothard of the Alternative ASEAN Network on Burma stated that mining operators used drugs on employees to improve productivity, with needles shared, raising the risk of HIV infection. Richard W. Hughes, a Bangkok-based gemologist makes the point that for every ruby sold through the junta, another gem that supports subsistence mining is smuggled over the Thai border.

The Chinese have also been the chief driving force behind Burma's gem mining industry and jade exports. The industry is completely under Chinese hands at every level, from the financiers, concession operators, all the way to the retail merchants that own scores of newly opened gem markets. One Chinese-owned jeweller reportedly controls 100 gem mines and produces over 2,000 kilograms of raw rubies annually. Since the privatization of the gem industry during the 1990s, Burmese jewelers and entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry have transformed Burma's gem industry into new retail jewelry shops, selling coveted pieces of expensive jewelry to customers mainly hailing from Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The permits for new gem mines in Mogoke, Mineshu and Nanyar state will be issued by the ministry according to a statement issued by the ministry on 11 February. While many sanctions placed on the former regime were eased or lifted in 2012, the US has left restrictions on importing rubies and jade from Myanmar intact. According to recent amendments to the new Myanmar foreign investment law, there is no longer a minimum capital requirement for investments, except in mining ventures, which require substantial proof of capital and must be documented through a domestic bank. Another important clarification in the investment law is the dropping of foreign ownership restrictions in joint ventures, except in restricted sectors, such as mining, where FDI will be capped at 80 per cent.

Myanmar is famed for its production of Golden South Sea Pearls. In recent years, the countries has auctioned its production in Hong Kong, first organized by Belpearl company in 2013 to critical acclaim and premium prices due to strong Chinese demand. Notable pearls include the New Dawn of Myanmar, a 19mm round golden pearl which sold to an anonymous buyer for undisclosed price.

Tourism

Main article: Tourism in BurmaSince 1992, the government has encouraged tourism. Until 2008, fewer than 750,000 tourists entered the country annually, but there has been substantial growth over the past years. In 2012, 1.06 million tourists visited the country, and 1.8 million are expected to visit by the end of 2013.

Tourism is a growing sector of the economy of Burma. Burma has diverse and varied tourist attractions and is served internationally by numerous airlines via direct flights. Domestic and foreign airlines also operate flights within the country. Cruise ships also dock at Yangon. Overland entry with a border pass is permitted at several border checkpoints. The government requires a valid passport with an entry visa for all tourists and business people. As of May 2010, foreign business visitors from any country can apply for a visa on arrival when passing through Yangon and Mandalay international airports without having to make any prior arrangements with travel agencies. Both the tourist visa and business visa are valid for 28 days, renewable for an additional 14 days for tourism and three months for business. Seeing Burma through a personal tour guide is popular. Travellers can hire guides through travel agencies.

Aung San Suu Kyi has requested that international tourists not visit Burma. Moreoever, the junta's forced labour programmes were focused on tourist destinations; these designations have been heavily criticised for their human rights records. Even disregarding the obviously governmental fees, Burma's Minister of Hotels and Tourism Major-General Saw Lwin admitted that the government receives a significant percentage of the income of private sector tourism services. In addition, only a very small minority of impoverished people in Burma receive any money with any relation to tourism.

Before 2012, much of the country was completely off-limits to tourists, and the military tightly controlled interactions between foreigners and the people of Burma. Locals were not allowed to discuss politics with foreigners, under penalty of imprisonment, and in 2001, the Myanmar Tourism Promotion Board issued an order for local officials to protect tourists and limit "unnecessary contact" between foreigners and ordinary Burmese people. Since 2012, Burma has opened up to more tourism and foreign capital, synonymous with the country's transition to democracy.

Infrastructure

The Myanmar Infrastructure Summit 2018 noted that Myanmar has an urgent need to "close its infrastructure gap", with an anticipated expenditure of US$120 billion funding its infrastructural projects between now and 2030. More specifically, infrastructural development in Myanmar should address three major challenges over the upcoming years: 1) Road modernization and integration with neighboring roads and transportation networks; 2) Development of regional airports and expansion of existing airport capacity, and 3) Maintenance and consolidation of urban transport infrastructure, through instalments of innovative transportation tools including but not limited to water-taxis and air-conditioned buses. Myanmar needs to scale up its enabling infrastructure like transport, power supply and public utilities.

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure projects may affect 24 million people in Myanmar living in the BRI corridors, thus transforming the allocation of economic benefits and losses among economic actors in the country.

External trade

| Sr. No. | Description | 2006–2007 Budget Trade Volume | 2006–2007 Real Trade Volume | |||||

| Export | Import | Trade Volume | Export | Import | Trade Volume | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal Trade | 4233.60 | 2468.40 | 6702.00 | 4585.47 | 2491.33 | 7076.80 | |

| 2 | Border Trade | 814.00 | 466.00 | 1280.00 | 647.21 | 445.40 | 1092.61 | |

| Total | 5047.60 | 2934.40 | 7982.00 | 5232.68 | 2936.73 | 8169.41 | ||

| No | Financial Year | Export Value | Import Value | Trade Value (US$, 000,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2006–2007 | 5222.92 | 2928.39 | 8151.31 |

| 2 | 2007–2008 | 6413.29 | 3346.64 | 9759.93 |

| 3 | 2008–2009 | 6792.85 | 4563.16 | 11356.01 |

| 4 | 2009–2010 | 7568.62 | 4186.28 | 11754.90 |

Macro-economic trends

This is a chart of trend of gross domestic product of Burma at market prices estimated by the International Monetary Fund and EconStats with figures in millions of Myanmar kyats.

| Year | Gross Domestic Product | US dollar exchange | Inflation index (2000=100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | 7,627 | ||

| 1970 | 10,437 | ||

| 1975 | 23,477 | ||

| 1980 | 38,608 | ||

| 1985 | 55,988 | ||

| 1990 | 151,941 | ||

| 1995 | 604,728 |

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 2004–2017.

| Year | GDP (in bil. US$ PPP) | GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) | GDP (in bil. US$ nominal) | GDP growth (real) | Inflation (in Percent) | Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 97.6 | 2,043 | 10.1 | 13.6% | 3.8% | 119% |

| 2005 | 114.3 | 2,381 | 11.4 | 13.6% | 10.7% | 110% |

| 2006 | 133.2 | 2,757 | 12.8 | 13.1% | 26.3% | 90% |

| 2007 | 153.2 | 3,150 | 16.8 | 12.0% | 30.9% | 62% |

| 2008 | 161.8 | 3,305 | 23.9 | 3.6% | 11.5% | 53% |

| 2009 | 171.4 | 3,476 | 29.0 | 5.1% | 2.2% | 55% |

| 2010 | 182.8 | 3,679 | 35.7 | 5.3% | 8.2% | 50% |

| 2011 | 197.0 | 3,933 | 50.3 | 5.6% | 2.8% | 46% |

| 2012 | 215.4 | 4,263 | 55.1 | 7.3% | 2.8% | 41% |

| 2013 | 237.3 | 4,656 | 59.2 | 8.4% | 5.7% | 33% |

| 2014 | 260.9 | 5,074 | 63.2 | 8.0% | 5.1% | 30% |

| 2015 | 282.1 | 5,443 | 62.7 | 7.0% | 10.0% | 34% |

| 2016 | 302.5 | 5,790 | 60.1 | 5.9% | 6.8% | 36% |

| 2017 | 328.7 | 6,244 | 61.3 | 6.7% | 5.1% | 35% |

According to the CIA World Factbook,

Burma, a resource-rich country, suffers from pervasive government controls, inefficient economic policies, and rural poverty. The junta took steps in the early 1990s to liberalize the economy after decades of failure under the "Burmese Way to Socialism," but those efforts stalled, and some of the liberalization measures were rescinded. Burma does not have monetary or fiscal stability, so the economy suffers from serious macroeconomic imbalances – including inflation, multiple official exchange rates that overvalue the Burmese kyat, and a distorted interest rate regime. Most overseas development assistance ceased after the junta began to suppress the democracy movement in 1988 and subsequently refused to honor the results of the 1990 legislative elections. In response to the government of Burma's attack in May 2003 on Aung San Suu Kyi and her convoy, the US imposed new economic sanctions against Burma – including a ban on imports of Burmese products and a ban on provision of financial services by US persons. A poor investment climate further slowed the inflow of foreign exchange. The most productive sectors will continue to be in extractive industries, especially oil and gas, mining, and timber. Other areas, such as manufacturing and services, are struggling with inadequate infrastructure, unpredictable import/export policies, deteriorating health and education systems, and corruption. A major banking crisis in 2003 shuttered the country's 20 private banks and disrupted the economy. As of December 2005, the largest private banks operate under tight restrictions limiting the private sector's access to formal credit. Official statistics are inaccurate. Published statistics on foreign trade are greatly understated because of the size of the black market and unofficial border trade – often estimated to be as large as the official economy. Burma's trade with Thailand, China, and India is rising. Though the Burmese government has good economic relations with its neighbors, better investment and business climates and an improved political situation are needed to promote foreign investment, exports, and tourism.

The economy saw continuous real GDP growth of at least 5% from 2009 onwards.

Foreign investment

Though foreign investment has been encouraged, it has so far met with only moderate success. The United States has placed trade sanctions on Burma. The European Union has placed embargoes on arms, non-humanitarian aid, visa bans on military regime leaders, and limited investment bans. Both the European Union and the US have placed sanctions on grounds of human rights violations in the country. Many nations in Asia, particularly India, Thailand and China have actively traded with Burma. However, on April 22, 2013, the EU suspended economic and political sanctions against Burma.

The public sector enterprises remain highly inefficient and also privatisation efforts have stalled. The estimates of Burmese foreign trade are highly ambiguous because of the great volume of black market trading. A major ongoing problem is the failure to achieve monetary and fiscal stability. One government initiative was to utilise Burma's large natural gas deposits. Currently, Burma has attracted investment from Thai, Malaysian, Filipino, Russian, Australian, Indian, and Singaporean companies. Trade with the US amounted to $243.56 million as of February 2013, accounting for 15 projects and just 0.58 per cent of the total, according to government statistics.

Asian investment

The Economist's special report on Burma points to increased economic activity resulting from Burma's political transformation and influx of foreign direct investment from Asian neighbours. Near the Mingaladon Industrial Park, for example, Japanese-owned factories have risen from the "debris" caused by "decades of sanctions and economic mismanagement." Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe has identified Burma as an economically attractive market that will help stimulate the Japanese economy. Among its various enterprises, Japan is helping build the Thilawa Port, which is part of the Thilawa Special Economic Zone, and helping fix the electricity supply in Yangon.

Japan is not the largest investor in Myanmar. "Thailand, for instance, the second biggest investor in Myanmar after China, is forging ahead with a bigger version of Thilawa at Dawei, on Myanmar's Tenasserim Coast ... Thai rulers have for centuries been toying with the idea of building a canal across the Kra Isthmus, linking the Gulf of Thailand directly to the Andaman Sea and the Indian Ocean to avoid the journey round peninsular Malaysia through the Strait of Malacca." Dawei would give Thailand that connection.

Chinese investment

Main article: BCIM Economic CorridorChina, by far the biggest investor in Burma, has focused on constructing oil and gas pipelines that "crisscross the country, starting from a new terminus at Kyaukphyu, just below Sittwe, up to Mandalay and on to the Chinese border town of Ruili and then Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province". This would prevent China from "having to funnel oil from Africa and the Middle East through the bottleneck around Singapore".

Since the Myanmar's military junta took power as the State Peace and Development Council junta in 1988, the ties between China's People's Liberation Army and Myanmar's military forces developed and formalised key ties between the two states. China became Myanmar's key source of aid, loans and other financial assistance. China remained Myanmar's biggest foreign investor in 2013 even after the economy opened up to other providers like Japan and India. Chinese monetary assistance allowed China to gain structural power of Myanmar and a dominant position within the natural resource sector. During this period, an underdeveloped Burmese industrial sector was driven in part by Chinese investment and consumption of a few key extractive sectors such as mining, driving domestic production away from consumer goods sectors like textiles and electronics.

Legal two-way trade between Burma and mainland China reached US$1.5 billion annually by 1988 and additional Chinese trade, investment, economic, and military aid was sought to invigorate and jumpstart the re-emerging Burmese economy. An influx of foreign capital investment from mainland China, Germany, and France has led to the development of new potential construction projects across Burma. Many of these infrastructure projects are in the hands of Chinese construction contractors and civil engineers with various projects such as irrigation dams, highways, bridges, ground satellite stations, and an international airport for Mandalay. Burmese entrepreneurs of Chinese ancestry have also established numerous joint ventures and corporate partnerships with mainland Chinese State-owned enterprises to facilitate the construction of oil pipelines that potentially could create thousands of jobs throughout the country. Private Chinese companies rely on the established overseas Chinese bamboo network as a conduit between mainland China and Burmese Chinese businesses to navigate the local economic landscape and facilitate trade between the two countries. Mainland China is now Burma's most important source of foreign goods and services as well as one of the most important sources of capital for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the country. In the fiscal year 2013, Chin accounted for 61 percent of all foreign direct investment. Between 2007 and 2015, Chinese FDI increased from US$775 million to US$21.867 billion accounting for 40 percent of all FDI in the country. Much of this investment went into Burma's energy and mining industries. Chinese private firms account for 87% percent of total legal cross-border trade at Ruili and have a considerable amount of structural power over the illicit economy of Myanmar. Chinese structural power over Burma's structure of finance also allows China to maintain a dominant position within the country's natural resource sector, primarily Burma's latent oil, gas, and uranium sectors. China's position as the country's primary investor also allows it to be its largest consumer of its extractive industries. Many Chinese state-owned enterprises have set their sights on Burma's high-value natural resource industries such as raw jade stones, teak and timber, rice, and marine fisheries.

Foreign aid

The level of international aid to Burma ranks amongst the lowest in the world (and the lowest in the Southeast Asian region)—Burma receives $4 per capita in development assistance, as compared to the average of $42.30 per capita.

In April 2007, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) identified the financial and other restrictions that the military government places on international humanitarian assistance in the Southeast Asian country. The GAO report, entitled "Assistance Programs Constrained in Burma," outlines the specific efforts of the Burmese government to hinder the humanitarian work of international organisations, including by restricting the free movement of international staff within the country. The report notes that the regime has tightened its control over assistance work since former Prime Minister Khin Nyunt was purged in October 2004.

Furthermore, the reports states that the military government passed guidelines in February 2006, which formalised Burma's restrictive policies. According to the report, the guidelines require that programs run by humanitarian groups "enhance and safeguard the national interest" and that international organisations co-ordinate with state agents and select their Burmese staff from government-prepared lists of individuals. United Nations officials have declared these restrictions unacceptable.

The shameful behavior of Burma's military regime in tying the hand of humanitarian organizations is laid out in these pages for all to see, and it must come to an end," said U.S. Representative Tom Lantos (D-CA). "In eastern Burma, where the military regime has burned or otherwise destroyed over 3,000 villages, humanitarian relief has been decimated. At least one million people have fled their homes and many are simply being left to die in the jungle."

US Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL) said that the report "underscores the need for democratic change in Burma, whose military regime arbitrarily arrests, tortures, rapes and executes its own people, ruthlessly persecutes ethnic minorities, and bizarrely builds itself a new capital city while failing to address the increasingly urgent challenges of refugee flows, illicit narcotics and human trafficking, and the spread of HIV/AIDS and other communicable diseases."

Other statistics

Electricity – production: 17,866.99 GWh (2016 est.)

Electricity – consumption: 7,572.60 GWh Residential, 4,650.90 GWh Industrial, 3,023.27 GWh Commercial, 2,384.89 GWh Loss (2016 est.)

Electricity – exports: 2,381.34 kWh (2016)

Electricity – imports: 0 kWh (2006)

Agriculture – products: rice, pulses, beans, sesame, groundnuts, watermelon, avocado sugarcane; hardwood; fish and fish products

Currency: 1 kyat (K) = 100 pyas

Exchange rates: kyats per US dollar – 1,205 (2008 est.), 1,296 (2007), 1,280 (2006), 5.82 (2005), 5.7459 (2004), 6.0764 (2003) note: unofficial exchange rates ranged in 2004 from 815 kyat/US dollar to nearly 970 kyat/US dollar, and by year end 2005, the unofficial exchange rate was 1,075 kyat/US dollar; data shown for 2003–05 are official exchange rates

Foreign Direct Investment In the first eight months, Myanmar has received investment of US$5.7 billion. Singapore has remained as the top source of foreign direct investments into Myanmar in the financial year of 2019-2020 with 20 Singapore-listed enterprises bringing in US$1.85 billion into Myanmar in the financial year 2019-2020. Hong Kong stood as the second-largest investors with an estimated capital of US$1.42 billion from 46 enterprises, followed by Japan investing $760 million in Myanmar.

Foreign Trade Total foreign trade reached over US$24.5 billion in the first eight months of the fiscal year (FY) 2019-2020 .

See also

References

- "Asian Development Bank and Myanmar: Economy". ADB.org. Asian Development Bank. 10 August 2022. Archived from the original on 26 March 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK". IMF. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- "Myanmar: Unlocking the Potential". Asian Development Bank. August 2014. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Robert H. (2009). The State in Myanmar. NUS Press. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-9971-69-466-1.

- ^ Steinberg, David I. (2001). Burma, the state of Myanmar. Georgetown University Press. pp. 125–127. ISBN 978-0-87840-893-1.

- Goodman, Michael K. (2010). Consuming space: placing consumption in perspective. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-7546-7229-6.

- "Myanmar - The initial impact of colonialism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Thant Myint-U. (2006). The river of lost footsteps : histories of Burma (1st ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6. OCLC 65064707.

- Davis, Mike (2001). Late Victorian holocausts: El Niño famines and the making of the third world. London: Verso. ISBN 1-85984-739-0. OCLC 45636958.

- Total. "Oil and Gas in Myanmar". Archived from the original on 15 April 2015.

- Steinberg, David I. (2002). Burma: The State of Myanmar. Georgetown University Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-1-58901-285-1.

- Booth, Anne (Spring 2003). "The Burma Development Disaster in Comparative Historical Perspective". SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research. 1 (1). ISSN 1479-8484. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Watkins, Thayer. "Political and Economic History of Myanmar (Burma) Economics". San Jose State University. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- Watkins, Thayer. "Political and Economic History of Myanmar (Burma) Economics". San José State University. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- Tallentire, Mark (28 September 2007). "The Burma road to ruin". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Kate Woodsome. "'Burmese Way to Socialism' Drives Country into Poverty". Archived from the original on 8 December 2012.

- "List of Least Developed Countries". UN-OHRLLS. 2005. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013.

- Stephen Codrington (2005). Planet geography. Solid Star Press. p. 559. ISBN 0-9579819-3-7.

- ^ "Burma Economy: Population, GDP, Inflation, Business, Trade, FDI, Corruption". Heritage.org. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Sean Turnell (29 March 2006). "Burma's Economic Prospects – Testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- "Research – CPI – Overview". Transparency.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Sean Turnell (2 May 2008). "The rape of Burma: where did the wealth go?". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- Feng Yingqiu (1 August 2011). "Myanmar starts to deal with official forex rate". Xinhua. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- McCartan, Brian (20 August 2008). "Myanmar exchange scam fleeces UN". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "Myanmar Considers Foreign-Exchange Overhaul". The Wall Street Journal. 8 August 2011. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "High Inflation Impeding Burma's Economy, Says NLD". The Irrawaddy. 30 April 2007. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- Fullbrook, David (4 November 2004). "So long US, hello China, India". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 6 November 2004. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- Joseph Allchin (20 September 2011). "Taste of democracy sends Burma's fragile economy into freefall". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- JOSEPH ALLCHINJOSEPH (23 September 2011). "Burma tells IMF of economic optimism". DVD. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- CHATRUDEE THEPARAT (28 August 2011). "Big-shift-to-dawei-predicted". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- Thein Linn (15–21 November 2010). "Dawei deep-sea port, SEZ gets green light". Myanmar times. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- Yap, Karl Lester M. (1 March 2012). "ADB Preparing First Myanmar Projects in 25 Years as Thein Opens". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- "ADB ends 30-year hiatus in Myanmar". Investvine.com. 28 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Aung Hla Htun (16 March 2012). "Exclusive: Myanmar drafts new foreign investment rules". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- "Myanmar clears 60% of foreign debt". Investvine.com. 29 January 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- "Myanmar FDI Expected to Jump 70%". InvestAsian.com. 7 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Calderon, Justin (30 May 2013). "Myanmar's economy to quadruple by 2030". Inside Investor. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- "In dirt-poor Myanmar, smartphones are transforming finance". The Economist. 12 October 2017. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "COVID-19, Coup d'Etat and Poverty: Compounding Negative Shocks and Their Impact on Human Development in Myanmar". United Nations. United Nations Development Program. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- "How the coup is destroying Myanmar's economy". East Asia Forum. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- "Military Coup Has Inflicted 'Permanent' Damage on Myanmar, World Bank Says". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ""The Latest @ USIP: For Myanmar's Economy to Recover, Military Rule Must End " Sean Turnell says". United States Institute of Peace. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- "Myanmar Economy in Tailspin, 2 Years after the Military Coup". dkiapcss.edu. February 2023. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- "'Riding a rollercoaster' in Myanmar's post-coup economy". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 24 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- "Myanmar plunges deeper into economic crisis". East Asia Forum.

- "An economically illiterate junta is running Myanmar into the ground". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- "37% jobless in Myanmar, study finds". Investvine.com. 26 January 2013. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Myat Mon (2008). "The Economic Position of Women in Burma". Asian Studies Review. 24 (2). Wiley: 243–255. doi:10.1080/10357820008713272. S2CID 144323033.

- "World Marriage Patterns 2000" (PDF). Un.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2003. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Jones, Gavin W. (2007). "Delayed Marriage and Very Low Fertility in Pacific Asia" (PDF). Population and Development Review. 33 (3). The Population Council, Inc.: 453–478. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00180.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- Ba-Thike, Katherine (1997). "Abortion: A Public Health Problem in Myanmar". Reproductive Health Matters. 5 (9): 94–100. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(97)90010-0. JSTOR 3775140.

- "Myanmar to reform investment body". Investvine.com. 5 February 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ "Burma: Rubies and Religion – Java Films". Javafilms.fr. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "On Patrol With Myanmar Rebels Fighting Both the Army and Drug Addiction – VICE News". Vice.com. 23 April 2015. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "Myanmar and IRRI" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2005. (21.2 KB), Facts About Cooperation, International Rice Research Institute. Retrieved on 25 September 2007.

- Calderon, Justin (21 June 2013). "Myanmar rice exports could double by 2020". Inside Investor. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "Drugs and Democracy – From Golden Triangle to Rubber Belt?". Tni.org. July 2009. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Brown, Ian (2005). A Colonial Economy in Crisis. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30580-2.

- ^ "Challenges to Democratization in Burma" (PDF). International IDEA. November 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 12 July 2006.

- Calderon, Justin (6 June 2013). "Energy: Myanmar's greatest challenge". Inside Investor. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Stokke, Kristian; Vakulchuk, Roman and Indra Overland (2018) Myanmar: A Political Economy Analysis. Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI). Report commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Gelb, S., Calabrese, L. and Tang. X. (2017). Foreign direct investment and economic transformation in Myanmar Archived 8 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. London: Supporting Economic Transformation programme

- Aung, Nyan Linn; Phyo, Pyae Thet (6 March 2008). "Government sets new daily minimum wage at K4800". Myanmar Times. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Pratruangkrai, Petchanet (17 March 2012). "Six top garment makers fleeing to low-wage Burma". The Nation. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ Thornton, Phil (12 February 2012). "Myanmar's rising drug trade". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- McCartan, Brian (13 July 2010). "Holes in Thailand's drug fences". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Macan-Markar, Marwaan (4 January 2011). "Myanmar's drug 'exports' to China test ties". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- "MYANMAR: Producing drugs for the region, fuelling addiction at home". IRIN. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 25 June 2010. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Kurlantzick, Joshua (16 February 2012). "Myanmar's Drug Problem". Asia Unbound. Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Sun Wyler, Liana (21 August 2008). "Burma and Transnational Crime" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- Chin, Ko-lin; Sheldon X. Zhang (April 2007). "The Chinese Connection: Cross-border Drug Trafficking between Myanmar and China" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice: 98. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Chin, Ko-lin (2009). The Golden Triangle: inside Southeast Asia's drug trade. Cornell University Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN 978-0-8014-7521-4.

- Lyman, Michael D.; Gary W. Potter (14 October 2010). Drugs in Society: Causes, Concepts and Control. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-4450-7.

- "Oil and Gas in Myanmar". Total S.A. Archived from the original on 12 December 2003. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- Ye Lwin (21 July 2008). "Oil and gas ranks second largest FDI at $3.24 billion". The Myanmar Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- ^ "Myanmar opens bids for 18 oil blocks". Investvine.com. 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- Vakulchuk, Roman; Kyaw Kyaw Hlaing; Edward Ziwa Naing; Indra Overland; Beni Suryadi and Sanjayan Velautham (2017). Myanmar's Attractiveness for Investment in the Energy Sector. A Comparative International Perspective. Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Myanmar Institute of Strategic and International Studies (MISIS) Report.

- DuByne, David (November 2015), "How Myanmar can Hedge Foreign Loans for Geothermal Projects to Mitigate Kyat Devaluation Risks" (PDF), OilSeedCrops.org, archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2015, retrieved 22 November 2015

- Gems of Burma and their Environmental Impact Archived 26 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Myanmar's Jade Millionaires Fuel Property Surge: Southeast Asia". The Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "CBC – Gem dealers push to ban Burmese rubies after bloody crackdown". Cbc.ca. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "Reuters, Move over, blood diamonds". Features.us.reuters.com. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Richard Hughes. "Burma Embargo & the Gem Trade". Ruby-sapphire.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Chang, Wen-chin; Tagliacozzo, Eric (13 April 2011). Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia. Duke University Press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 978-0-8223-4903-7.

- Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-385-72186-8.

- "Mining block permits issued in Myanmar". Investvine.com. 20 February 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- "Belpearl Auctions: Connecting the pearl business to global markets". jewellerynet.com. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

- Choi, Christy (8 March 2013). "Myanmar's golden pearls fetch top price at auction". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Henderson, Joan C. "The Politics of Tourism in Myanmar" (PDF). Nanyang Technological University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- "Tourism Statistic". Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- "Industry applauds visa on arrival 'breakthrough' | Myanmar Times". Archived from the original on 21 June 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Henderson, Joan C. "The Politics of Tourism in Myanmar" (PDF). Nanyang Technological University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- "Tayzathuria". Tayzathuria.org.uk. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- The Tourism Campaign – Campaigns – The Burma Campaign UK Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "World Bank Group. Myanmar Economic Monitor May 2018" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- Mark, S., Overland, I. and Vakulchuk, R., 2020. Sharing the Spoils: Winners and Losers in the Belt and Road Initiative in Myanmar. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 39(3), pp.381-404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1868103420962116

- "Myanmar TradeNet". Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Calderon, Justin (24 April 2013). "End of EU sanctions augurs Myanmar rush". Inside Investor. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- "VOL NO REGD NO DA 1589". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- Calderon, Justin (29 April 2013). "US to boost Myanmar trade, investment". Inside Investor. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ "Geopolitical consequences: Rite of passage". The Economist. 25 May 2013. Archived from the original on 31 May 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Reeves, Jeffrey (2015). Chinese Foreign Relations with Weak Peripheral States: Asymmetrical Economic Power and Insecurity. Asian Security Studies. Routledge (published 2 November 2015). pp. 153–156. ISBN 978-1-138-89150-0.

- Miller, Tom (2017). China's Asian Dream: Empire Building Along the New Silk Road. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-78360-923-9.

- Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. pp. 25. ISBN 978-0-385-72186-8.

- Santasombat, Yos (2015). Impact of China's Rise on the Mekong Region. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-69307-8.

- Santasombat, Yos (2017). Chinese Capitalism in Southeast Asia: Cultures and Practices. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 234–236. ISBN 978-981-10-4695-7.

- Santasombat, Yos (2017). Chinese Capitalism in Southeast Asia: Cultures and Practices. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 235. ISBN 978-981-10-4695-7.

- Reeves, Jeffrey (2015). Chinese Foreign Relations with Weak Peripheral States: Asymmetrical Economic Power and Insecurity. Asian Security Studies. Routledge (published 2 November 2015). pp. 151–156. ISBN 978-1-138-89150-0.

- Santasombat, Yos (2017). Chinese Capitalism in Southeast Asia: Cultures and Practices. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-981-10-4695-7.

- Wade, Francis (2 March 2011). "UK to become top donor to Burma". Democratic Voice of Burma. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "Burma". Refugees International. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "Australia's aid to Burma—Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". AusAid. Government of Australia. 30 June 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "Myanmar's rulers implement increasingly restrictive regulations for aid-giving agencies". International Herald Tribune. 19 April 2007.

- ^ "Myanmar Energy Statistics 2019" (PDF). Myanmar Ministry of Electricity and Energy: 20–21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Singapore tops source of FDIs in Myanmar in 2020-2021FY". consult-myanmar.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Myanmar's foreign trade reaches over 24 bln USD in 8 months". www.xinhuanet.com. 4 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020.

Further reading

- Myanmar Business Today; Print Edition, 5 November 2015. Geothermal Energy in Myanmar, Securing Electricity for Eastern Border Development Archived 20 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, by David DuByne & Hishamuddin Koh

- Myanmar Business Today; Print Edition, 19 June 2014. Myanmar's Institutional Infrastructure Constraints and How to Fill the Gaps Archived 13 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, by David DuByne & Hishamuddin Koh

- Myanmar Business Today; Print Edition, 27 February 2014. A Roadmap to Building Myanmar into the Food Basket of Asia, by David DuByne & Hishamuddin Koh

- Taipei American Chamber of Commerce; Topics Magazine, Analysis, November 2012. Myanmar: Southeast Asia's Last Frontier for Investment Archived 25 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, by David DuByne

- Taiwan ASEAN Studies Center; ASEAN Outlook Magazine, May 2013. Myanmar's Overlooked Industry Opportunities and Investment Climate Archived 28 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, by David DuByne

- Myanmar Economic Monitor Report June 2023 (English); The World Bank, 28 June 2023. June 2023 Myanmar Economic Monitor : A Fragile Recovery - Special Focus on Employment, Incomes and Coping Mechanisms (English) Archived 4 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine, by Edwards,Kim Alan, Mansaray,Kemoh Myint,Thi Da Hayati,Fayavar Maw,Aka Kyaw Min

External links

- Google Earth Map of oil and gas infrastructure in Myanmar Archived 12 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Myanmar Ministry of Commerce (MMC) News, information, journals, magazines related to Burmese business and commerce

- Myanmar-US Chamber of Commerce

- Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI) Archived 23 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Myanmar Archived 12 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

| Economy of Asia | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other territories | |