Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) or electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy is a method for studying materials that have unpaired electrons. The basic concepts of EPR are analogous to those of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), but the spins excited are those of the electrons instead of the atomic nuclei. EPR spectroscopy is particularly useful for studying metal complexes and organic radicals. EPR was first observed in Kazan State University by Soviet physicist Yevgeny Zavoisky in 1944, and was developed independently at the same time by Brebis Bleaney at the University of Oxford.

Theory

Origin of an EPR signal

Every electron has a magnetic moment and spin quantum number , with magnetic components or . In the presence of an external magnetic field with strength , the electron's magnetic moment aligns itself either antiparallel () or parallel () to the field, each alignment having a specific energy due to the Zeeman effect:

where

- is the electron's so-called g-factor (see also the Landé g-factor), for the free electron,

- is the Bohr magneton.

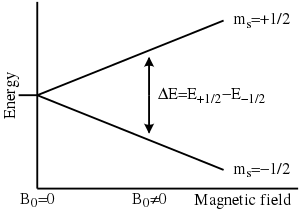

Therefore, the separation between the lower and the upper state is for unpaired free electrons. This equation implies (since both and are constant) that the splitting of the energy levels is directly proportional to the magnetic field's strength, as shown in the diagram below.

An unpaired electron can change its electron spin by either absorbing or emitting a photon of energy such that the resonance condition, , is obeyed. This leads to the fundamental equation of EPR spectroscopy: .

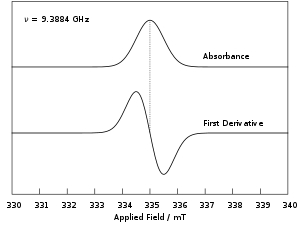

Experimentally, this equation permits a large combination of frequency and magnetic field values, but the great majority of EPR measurements are made with microwaves in the 9000–10000 MHz (9–10 GHz) region, with fields corresponding to about 3500 G (0.35 T). Furthermore, EPR spectra can be generated by either varying the photon frequency incident on a sample while holding the magnetic field constant or doing the reverse. In practice, it is usually the frequency that is kept fixed. A collection of paramagnetic centers, such as free radicals, is exposed to microwaves at a fixed frequency. By increasing an external magnetic field, the gap between the and energy states is widened until it matches the energy of the microwaves, as represented by the double arrow in the diagram above. At this point the unpaired electrons can move between their two spin states. Since there typically are more electrons in the lower state, due to the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution (see below), there is a net absorption of energy, and it is this absorption that is monitored and converted into a spectrum. The upper spectrum below is the simulated absorption for a system of free electrons in a varying magnetic field. The lower spectrum is the first derivative of the absorption spectrum. The latter is the most common way to record and publish continuous wave EPR spectra.

For the microwave frequency of 9388.4 MHz, the predicted resonance occurs at a magnetic field of about = 0.3350 T = 3350 G

Because of electron-nuclear mass differences, the magnetic moment of an electron is substantially larger than the corresponding quantity for any nucleus, so that a much higher electromagnetic frequency is needed to bring about a spin resonance with an electron than with a nucleus, at identical magnetic field strengths. For example, for the field of 3350 G shown above, spin resonance occurs near 9388.2 MHz for an electron compared to only about 14.3 MHz for H nuclei. (For NMR spectroscopy, the corresponding resonance equation is where and depend on the nucleus under study.)

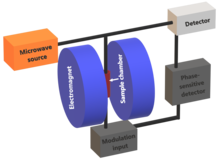

Field modulation

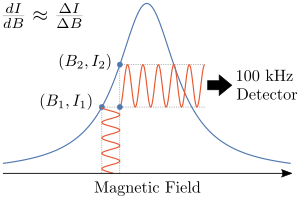

As previously mentioned an EPR spectrum is usually directly measured as the first derivative of the absorption. This is accomplished by using field modulation. A small additional oscillating magnetic field is applied to the external magnetic field at a typical frequency of 100 kHz. By detecting the peak to peak amplitude the first derivative of the absorption is measured. By using phase sensitive detection only signals with the same modulation (100 kHz) are detected. This results in higher signal to noise ratios. Note field modulation is unique to continuous wave EPR measurements and spectra resulting from pulsed experiments are presented as absorption profiles.

The same idea underlies the Pound-Drever-Hall technique for frequency locking of lasers to a high-finesse optical cavity.

Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution

In practice, EPR samples consist of collections of many paramagnetic species, and not single isolated paramagnetic centers. If the population of radicals is in thermodynamic equilibrium, its statistical distribution is described by the Boltzmann distribution:

where is the number of paramagnetic centers occupying the upper energy state, is the Boltzmann constant, and is the thermodynamic temperature. At 298 K, X-band microwave frequencies ( ≈ 9.75 GHz) give ≈ 0.998, meaning that the upper energy level has a slightly smaller population than the lower one. Therefore, transitions from the lower to the higher level are more probable than the reverse, which is why there is a net absorption of energy.

The sensitivity of the EPR method (i.e., the minimal number of detectable spins ) depends on the photon frequency according to

where is a constant, is the sample's volume, is the unloaded quality factor of the microwave cavity (sample chamber), is the cavity filling coefficient, and is the microwave power in the spectrometer cavity. With and being constants, ~ , i.e., ~ , where ≈ 1.5. In practice, can change varying from 0.5 to 4.5 depending on spectrometer characteristics, resonance conditions, and sample size.

A great sensitivity is therefore obtained with a low detection limit and a large number of spins. Therefore, the required parameters are:

- A high spectrometer frequency to minimize the Eq. 2. Common frequencies are discussed below

- A low temperature to decrease the number of spin at the high level of energy as shown in Eq. 1. This condition explains why spectra are often recorded on sample at the boiling point of liquid nitrogen or liquid helium.

Spectral parameters

In real systems, electrons are normally not solitary, but are associated with one or more atoms. There are several important consequences of this:

- An unpaired electron can gain or lose angular momentum, which can change the value of its g-factor, causing it to differ from . This is especially significant for chemical systems with transition-metal ions.

- Systems with multiple unpaired electrons experience electron–electron interactions that give rise to "fine" structure. This is realized as zero field splitting and exchange coupling, and can be large in magnitude.

- The magnetic moment of a nucleus with a non-zero nuclear spin will affect any unpaired electrons associated with that atom. This leads to the phenomenon of hyperfine coupling, analogous to J-coupling in NMR, splitting the EPR resonance signal into doublets, triplets and so forth. Additional smaller splittings from nearby nuclei is sometimes termed "superhyperfine" coupling.

- Interactions of an unpaired electron with its environment influence the shape of an EPR spectral line. Line shapes can yield information about, for example, rates of chemical reactions.

- These effects (g-factor, hyperfine coupling, zero field splitting, exchange coupling) in an atom or molecule may not be the same for all orientations of an unpaired electron in an external magnetic field. This anisotropy depends upon the electronic structure of the atom or molecule (e.g., free radical) in question, and so can provide information about the atomic or molecular orbital containing the unpaired electron.

The g factor

Knowledge of the g-factor can give information about a paramagnetic center's electronic structure. An unpaired electron responds not only to a spectrometer's applied magnetic field but also to any local magnetic fields of atoms or molecules. The effective field experienced by an electron is thus written

where includes the effects of local fields ( can be positive or negative). Therefore, the resonance condition (above) is rewritten as follows:

The quantity is denoted and called simply the g-factor, so that the final resonance equation becomes

This last equation is used to determine in an EPR experiment by measuring the field and the frequency at which resonance occurs. If does not equal , the implication is that the ratio of the unpaired electron's spin magnetic moment to its angular momentum differs from the free-electron value. Since an electron's spin magnetic moment is constant (approximately the Bohr magneton), then the electron must have gained or lost angular momentum through spin–orbit coupling. Because the mechanisms of spin–orbit coupling are well understood, the magnitude of the change gives information about the nature of the atomic or molecular orbital containing the unpaired electron.

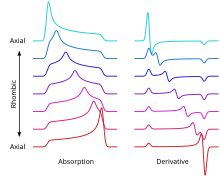

In general, the g factor is not a number but a 3×3 matrix. The principal axes of this tensor are determined by the local fields, for example, by the local atomic arrangement around the unpaired spin in a solid or in a molecule. Choosing an appropriate coordinate system (say, x,y,z) allows one to "diagonalize" this tensor, thereby reducing the maximal number of its components from 9 to 3: gxx, gyy and gzz. For a single spin experiencing only Zeeman interaction with an external magnetic field, the position of the EPR resonance is given by the expression gxxBx + gyyBy + gzzBz. Here Bx, By and Bz are the components of the magnetic field vector in the coordinate system (x,y,z); their magnitudes change as the field is rotated, so does the frequency of the resonance. For a large ensemble of randomly oriented spins (as in a fluid solution), the EPR spectrum consists of three peaks of characteristic shape at frequencies gxxB0, gyyB0 and gzzB0.

In first-derivative spectrum, the low-frequency peak is positive, the high-frequency peak is negative, and the central peak is bipolar. Such situations are commonly observed in powders, and the spectra are therefore called "powder-pattern spectra". In crystals, the number of EPR lines is determined by the number of crystallographically equivalent orientations of the EPR spin (called "EPR center").

At higher temperatures, the three peaks coalesce to a singlet, corresponding to giso, for isotropic. The relationship between giso and the components is:

One elementary step in analyzing an EPR spectrum is to compare giso with the g-factor for the free electron, ge. Metal-based radicals giso is typically well above ge whereas organic radicals, giso ~ ge.

The determination of the absolute value of the g factor is challenging due to the lack of a precise estimate of the local magnetic field at the sample location. Therefore, typically so-called g factor standards are measured together with the sample of interest. In the common spectrum, the spectral line of the g factor standard is then used as a reference point to determine the g factor of the sample. For the initial calibration of g factor standards, Herb et al. introduced a precise procedure by using double resonance techniques based on the Overhauser shift.

Hyperfine coupling

Since the source of an EPR spectrum is a change in an electron's spin state, the EPR spectrum for a radical (S = 1/2 system) would consist of one line. Greater complexity arises because the spin couples with nearby nuclear spins. The magnitude of the coupling is proportional to the magnetic moment of the coupled nuclei and depends on the mechanism of the coupling. Coupling is mediated by two processes, dipolar (through space) and isotropic (through bond).

This coupling introduces additional energy states and, in turn, multi-lined spectra. In such cases, the spacing between the EPR spectral lines indicates the degree of interaction between the unpaired electron and the perturbing nuclei. The hyperfine coupling constant of a nucleus is directly related to the spectral line spacing and, in the simplest cases, is essentially the spacing itself.

Two common mechanisms by which electrons and nuclei interact are the Fermi contact interaction and by dipolar interaction. The former applies largely to the case of isotropic interactions (independent of sample orientation in a magnetic field) and the latter to the case of anisotropic interactions (spectra dependent on sample orientation in a magnetic field). Spin polarization is a third mechanism for interactions between an unpaired electron and a nuclear spin, being especially important for -electron organic radicals, such as the benzene radical anion. The symbols "a" or "A" are used for isotropic hyperfine coupling constants, while "B" is usually employed for anisotropic hyperfine coupling constants.

In many cases, the isotropic hyperfine splitting pattern for a radical freely tumbling in a solution (isotropic system) can be predicted.

Multiplicity

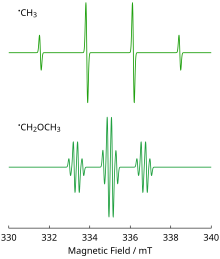

- For a radical having M equivalent nuclei, each with a spin of I, the number of EPR lines expected is 2MI + 1. As an example, the methyl radical, CH3, has three H nuclei, each with I = 1/2, and so the number of lines expected is 2MI + 1 = 2(3)(1/2) + 1 = 4, which is as observed.

- For a radical having M1 equivalent nuclei, each with a spin of I1, and a group of M2 equivalent nuclei, each with a spin of I2, the number of lines expected is (2M1I1 + 1) (2M2I2 + 1). As an example, the methoxymethyl radical, H

2C(OCH

3) has two equivalent H nuclei, each with I = 1/2 and three equivalent H nuclei each with I = 1/2, and so the number of lines expected is (2M1I1 + 1) (2M2I2 + 1) = = 3×4 = 12, again as observed. - The above can be extended to predict the number of lines for any number of nuclei.

While it is easy to predict the number of lines, the reverse problem, unraveling a complex multi-line EPR spectrum and assigning the various spacings to specific nuclei, is more difficult.

In the often encountered case of I = 1/2 nuclei (e.g., H, F, P), the line intensities produced by a population of radicals, each possessing M equivalent nuclei, will follow Pascal's triangle. For example, the spectrum at the right shows that the three H nuclei of the CH3 radical give rise to 2MI + 1 = 2(3)(1/2) + 1 = 4 lines with a 1:3:3:1 ratio. The line spacing gives a hyperfine coupling constant of aH = 23 G for each of the three H nuclei. Note again that the lines in this spectrum are first derivatives of absorptions.

As a second example, the methoxymethyl radical, H3COCH2 the OCH2 center will give an overall 1:2:1 EPR pattern, each component of which is further split by the three methoxy hydrogens into a 1:3:3:1 pattern to give a total of 3×4 = 12 lines, a triplet of quartets. A simulation of the observed EPR spectrum is shown and agrees with the 12-line prediction and the expected line intensities. Note that the smaller coupling constant (smaller line spacing) is due to the three methoxy hydrogens, while the larger coupling constant (line spacing) is from the two hydrogens bonded directly to the carbon atom bearing the unpaired electron. It is often the case that coupling constants decrease in size with distance from a radical's unpaired electron, but there are some notable exceptions, such as the ethyl radical (CH2CH3).

Resonance linewidth definition

Resonance linewidths are defined in terms of the magnetic induction B and its corresponding units, and are measured along the x axis of an EPR spectrum, from a line's center to a chosen reference point of the line. These defined widths are called halfwidths and possess some advantages: for asymmetric lines, values of left and right halfwidth can be given. The halfwidth is the distance measured from the line's center to the point in which absorption value has half of maximal absorption value in the center of resonance line. First inclination width is a distance from center of the line to the point of maximal absorption curve inclination. In practice, a full definition of linewidth is used. For symmetric lines, halfwidth , and full inclination width .

Applications

EPR/ESR spectroscopy is used in various branches of science, such as biology, chemistry and physics, for the detection and identification of free radicals in the solid, liquid, or gaseous state, and in paramagnetic centers such as F-centers.

Chemical reactions

EPR is a sensitive, specific method for studying both radicals formed in chemical reactions and the reactions themselves. For example, when ice (solid H2O) is decomposed by exposure to high-energy radiation, radicals such as H, OH, and HO2 are produced. Such radicals can be identified and studied by EPR. Organic and inorganic radicals can be detected in electrochemical systems and in materials exposed to UV light. In many cases, the reactions to make the radicals and the subsequent reactions of the radicals are of interest, while in other cases EPR is used to provide information on a radical's geometry and the orbital of the unpaired electron.

EPR is useful in homogeneous catalysis research for characterization of paramagnetic complexes and reactive intermediates. EPR spectroscopy is a particularly useful tool to investigate their electronic structures, which is fundamental to understand their reactivity.

EPR/ESR spectroscopy can be applied only to systems in which the balance between radical decay and radical formation keeps the free radicals concentration above the detection limit of the spectrometer used. This can be a particularly severe problem in studying reactions in liquids. An alternative approach is to slow down reactions by studying samples held at cryogenic temperatures, such as 77 K (liquid nitrogen) or 4.2 K (liquid helium). An example of this work is the study of radical reactions in single crystals of amino acids exposed to x-rays, work that sometimes leads to activation energies and rate constants for radical reactions.

Medical and biological

Medical and biological applications of EPR also exist. Although radicals are very reactive, so they do not normally occur in high concentrations in biology, special reagents have been developed to attach "spin labels", also called "spin probes", to molecules of interest. Specially-designed nonreactive radical molecules can attach to specific sites in a biological cell, and EPR spectra then give information on the environment of the spin labels. Spin-labeled fatty acids have been extensively used to study dynamic organisation of lipids in biological membranes, lipid-protein interactions and temperature of transition of gel to liquid crystalline phases. Injection of spin-labeled molecules allows for electron resonance imaging of living organisms.

A type of dosimetry system has been designed for reference standards and routine use in medicine, based on EPR signals of radicals from irradiated polycrystalline α-alanine (the alanine deamination radical, the hydrogen abstraction radical, and the (CO(OH))=C(CH3)NH+2 radical). This method is suitable for measuring gamma and X-rays, electrons, protons, and high-linear energy transfer (LET) radiation of doses in the 1 Gy to 100 kGy range.

EPR can be used to measure microviscosity and micropolarity within drug delivery systems as well as the characterization of colloidal drug carriers.

The study of radiation-induced free radicals in biological substances (for cancer research) poses the additional problem that tissue contains water, and water (due to its electric dipole moment) has a strong absorption band in the microwave region used in EPR spectrometers.

Material characterization

EPR/ESR spectroscopy is used in geology and archaeology as a dating tool. It can be applied to a wide range of materials such as organic shales, carbonates, sulfates, phosphates, silica or other silicates. When applied to shales, the EPR data correlates to the maturity of the kerogen in the shale.

EPR spectroscopy has been used to measure properties of crude oil, such as determination of asphaltene and vanadium content. The free-radical component of the EPR signal is proportional to the amount of asphaltene in the oil regardless of any solvents, or precipitants that may be present in that oil. When the oil is subject to a precipitant such as hexane, heptane, pyridine however, then much of the asphaltene can be subsequently extracted from the oil by gravimetric techniques. The EPR measurement of that extract will then be function of the polarity of the precipitant that was used. Consequently, it is preferable to apply the EPR measurement directly to the crude. In the case that the measurement is made upstream of a separator (oil production), then it may also be necessary determine the oil fraction within the crude (e.g., if a certain crude contains 80% oil and 20% water, then the EPR signature will be 80% of the signature of downstream of the separator).

EPR has been used by archaeologists for the dating of teeth. Radiation damage over long periods of time creates free radicals in tooth enamel, which can then be examined by EPR and, after proper calibration, dated. Similarly, material extracted from the teeth of people during dental procedures can be used to quantify their cumulative exposure to ionizing radiation. People (and other mammals) exposed to radiation from the atomic bombs, from the Chernobyl disaster, and from the Fukushima accident have been examined by this method.

Radiation-sterilized foods have been examined with EPR spectroscopy, aiming to develop methods to determine whether a food sample has been irradiated and to what dose.

Electrochemistry Applications

EPR is a very important technique in the electrochemical field because it operates to detect paramagnetic species and unpaired electrons. The technique has a long history of being coupled to the field, starting with a report in 1958 using EPR to detect free radicals generated via electrochemistry. In an experiment performed by Austen, Given, Ingram, and Peover, solutions of aromatics were electrolyzed and placed into an EPR instrument, resulting in a broad signal response. While this result could not be used for any specific identification, the presence of an EPR signal validated the theory that free radical species were involved in electron transfer reactions as an intermediate state. Soon after, other groups discovered the possibility of coupling in situ electrolysis with EPR, producing the first resolved spectra of the nitrobenzene anion radical from a mercury electrode sealed within the instrument cavity. Since then, the impact of EPR on the field of electrochemistry has only expanded, serving as a way to monitor free radicals produced by other electrolysis reactions.

In more recent years, EPR has also been used within the context of electrochemistry to study redox-flow reactions and batteries. Because of the in situ possibilities, it is possible to construct an electrochemical cell inside the EPR instrument and capture the short-lived intermediates involved at lower concentrations than necessitated for NMR. Often, NMR and EPR experiments are coupled to get a full picture of the electrochemical reaction over time. It is also possible to determine the concentration of a specific radical species via EPR, as it is proportional to the double integral of the EPR signal as referenced to a calibration standard. A specific application example can be seen in Lithium ion batteries, specifically studying Li-S battery sulfate ion formation or in Li-O2 battery oxygen radical formation via the 4-oxo-TEMP to 4-oxo-TEMPO conversion.

Other electrochemical applications to EPR can be found in the context of water purification reactions and oxygen reduction reactions. In water purification reactions, reactive radical species such as singlet oxygen and hydroxyl, oxygen, and hydrogen radicals are consistently present, generated electrochemically in the breakdown of water pollutants. These intermediates are highly reactive and unstable, thus necessitating a technique such as EPR that can identify radical species specifically.

Other applications

In the field of quantum computing, pulsed EPR is used to control the state of electron spin qubits in materials such as diamond, silicon and gallium arsenide.

High-field high-frequency measurements

High-field high-frequency EPR measurements are sometimes needed to detect subtle spectroscopic details. However, for many years the use of electromagnets to produce the needed fields above 1.5 T was impossible, due principally to limitations of traditional magnet materials. The first multifunctional millimeter EPR spectrometer with a superconducting solenoid was described in the early 1970s by Y. S. Lebedev's group (Russian Institute of Chemical Physics, Moscow) in collaboration with L. G. Oranski's group (Ukrainian Physics and Technics Institute, Donetsk), which began working in the Institute of Problems of Chemical Physics, Chernogolovka around 1975. Two decades later, a W-band EPR spectrometer was produced as a small commercial line by the German Bruker Company, initiating the expansion of W-band EPR techniques into medium-sized academic laboratories.

| Waveband | L | S | C | X | P | K | Q | U | V | E | W | F | D | — | J | — |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | 100 | 75 | 30 | 20 | 12.5 | 8.5 | 6 | 4.6 | 4 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.83 | |

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 15 | 24 | 35 | 50 | 65 | 75 | 95 | 111 | 140 | 190 | 285 | 360 | |

| 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.86 | 1.25 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 6.8 | 10.2 | 12.8 |

The EPR waveband is stipulated by the frequency or wavelength of a spectrometer's microwave source (see Table).

EPR experiments often are conducted at X and, less commonly, Q bands, mainly due to the ready availability of the necessary microwave components (which originally were developed for radar applications). A second reason for widespread X and Q band measurements is that electromagnets can reliably generate fields up to about 1 tesla. However, the low spectral resolution over g-factor at these wavebands limits the study of paramagnetic centers with comparatively low anisotropic magnetic parameters. Measurements at > 40 GHz, in the millimeter wavelength region, offer the following advantages:

- EPR spectra are simplified due to the reduction of second-order effects at high fields.

- Increase in orientation selectivity and sensitivity in the investigation of disordered systems.

- The informativity and precision of pulse methods, e.g., ENDOR also increase at high magnetic fields.

- Accessibility of spin systems with larger zero-field splitting due to the larger microwave quantum energy h.

- The higher spectral resolution over g-factor, which increases with irradiation frequency and external magnetic field B0. This is used to investigate the structure, polarity, and dynamics of radical microenvironments in spin-modified organic and biological systems through the spin label and probe method. The figure shows how spectral resolution improves with increasing frequency.

- Saturation of paramagnetic centers occurs at a comparatively low microwave polarizing field B1, due to the exponential dependence of the number of excited spins on the radiation frequency . This effect can be successfully used to study the relaxation and dynamics of paramagnetic centers as well as of superslow motion in the systems under study.

- The cross-relaxation of paramagnetic centers decreases dramatically at high magnetic fields, making it easier to obtain more-precise and more-complete information about the system under study.

This was demonstrated experimentally in the study of various biological, polymeric and model systems at D-band EPR.

Hardware components

Microwave bridge

The microwave bridge contains both the microwave source and the detector. Older spectrometers used a vacuum tube called a klystron to generate microwaves, but modern spectrometers use a Gunn diode. Immediately after the microwave source there is an isolator which serves to attenuate any reflections back to the source which would result in fluctuations in the microwave frequency. The microwave power from the source is then passed through a directional coupler which splits the microwave power into two paths, one directed towards the cavity and the other the reference arm. Along both paths there is a variable attenuator that facilitates the precise control of the flow of microwave power. This in turn allows for accurate control over the intensity of the microwaves subjected to the sample. On the reference arm, after the variable attenuator there is a phase shifter that sets a defined phase relationship between the reference and reflected signal which permits phase sensitive detection.

Most EPR spectrometers are reflection spectrometers, meaning that the detector should only be exposed to microwave radiation coming back from the cavity. This is achieved by the use of a device known as the circulator which directs the microwave radiation (from the branch that is heading towards the cavity) into the cavity. Reflected microwave radiation (after absorption by the sample) is then passed through the circulator towards the detector, ensuring it does not go back to the microwave source. The reference signal and reflected signal are combined and passed to the detector diode which converts the microwave power into an electrical current.

Reference arm

At low energies (less than 1 μW) the diode current is proportional to the microwave power and the detector is referred to as a square-law detector. At higher power levels (greater than 1 mW) the diode current is proportional to the square root of the microwave power and the detector is called a linear detector. In order to obtain optimal sensitivity as well as quantitative information the diode should be operating within the linear region. To ensure the detector is operating at that level the reference arm serves to provide a "bias".

Magnet

In an EPR spectrometer the magnetic assembly includes the magnet with a dedicated power supply as well as a field sensor or regulator such as a Hall probe. EPR spectrometers use one of two types of magnet which is determined by the operating microwave frequency (which determine the range of magnetic field strengths required). The first is an electromagnet which are generally capable of generating field strengths of up to 1.5 T making them suitable for measurements using the Q-band frequency. In order to generate field strengths appropriate for W-band and higher frequency operation superconducting magnets are employed. The magnetic field is homogeneous across the sample volume and has a high stability at static field.

Microwave resonator (cavity)

The microwave resonator is designed to enhance the microwave magnetic field at the sample in order to induce EPR transitions. It is a metal box with a rectangular or cylindrical shape that resonates with microwaves (like an organ pipe with sound waves). At the resonance frequency of the cavity microwaves remain inside the cavity and are not reflected back. Resonance means the cavity stores microwave energy and its ability to do this is given by the quality factor Q, defined by the following equation:

The higher the value of Q the higher the sensitivity of the spectrometer. The energy dissipated is the energy lost in one microwave period. Energy may be lost to the side walls of the cavity as microwaves may generate currents which in turn generate heat. A consequence of resonance is the creation of a standing wave inside the cavity. Electromagnetic standing waves have their electric and magnetic field components exactly out of phase. This provides an advantage as the electric field provides non-resonant absorption of the microwaves, which in turn increases the dissipated energy and reduces Q. To achieve the largest signals and hence sensitivity the sample is positioned such that it lies within the magnetic field maximum and the electric field minimum. When the magnetic field strength is such that an absorption event occurs, the value of Q will be reduced due to the extra energy loss. This results in a change of impedance which serves to stop the cavity from being critically coupled. This means microwaves will now be reflected back to the detector (in the microwave bridge) where an EPR signal is detected.

Pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance

Further information: Pulsed electron paramagnetic resonanceThe dynamics of electron spins are best studied with pulsed measurements. Microwave pulses typically 10–100 ns long are used to control the spins in the Bloch sphere. The spin–lattice relaxation time can be measured with an inversion recovery experiment.

As with pulsed NMR, the Hahn echo is central to many pulsed EPR experiments. A Hahn echo decay experiment can be used to measure the dephasing time, as shown in the animation below. The size of the echo is recorded for different spacings of the two pulses. This reveals the decoherence, which is not refocused by the pulse. In simple cases, an exponential decay is measured, which is described by the time.

Pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance could be advanced into electron nuclear double resonance spectroscopy (ENDOR), which utilizes waves in the radio frequencies. Since different nuclei with unpaired electrons respond to different wavelengths, radio frequencies are required at times. Since the results of the ENDOR gives the coupling resonance between the nuclei and the unpaired electron, the relationship between them can be determined.

See also

- Dynamic nuclear polarisation

- EDMR

- Electric dipole spin resonance

- Electron resonance imaging

- Ferromagnetic resonance

- Optically detected magnetic resonance

- Site-directed spin labeling

- Spin label

- Spin trapping

- Albumin transport function analysis by EPR spectroscopy

References

- Zavoisky E (1945). "Spin-magnetic resonance in paramagnetics". J. Phys. (USSR). 9: 245.

- Zavoisky E (1944). Paramagnetic Absorption in Perpendicular and Parallel Fields for Salts, Solutions and Metals (PhD thesis).

- Odom B, Hanneke D, D'Urso B, Gabrielse G (July 2006). "New measurement of the electron magnetic moment using a one-electron quantum cyclotron". Physical Review Letters. 97 (3): 030801. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..97c0801O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.030801. PMID 16907490.

- ^ Chechik V, Carter E, Murphy D (2016). Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-872760-6. OCLC 945390515.

- Levine IN (1975). Molecular Spectroscopy. Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-471-53128-9.

- Herb K, Tschaggelar R, Denninger G, Jeschke G (April 2018). "Double resonance calibration of g factor standards: Carbon fibers as a high precision standard". Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 289: 100–106. Bibcode:2018JMagR.289..100H. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2018.02.006. hdl:20.500.11850/245192. PMID 29476927.

- Encyclopedia of Spectroscopy and Spectrometry. Academic Press. 2016. pp. 521, 528. ISBN 9780128032251.

- Strictly speaking, "a" refers to the hyperfine splitting constant, a line spacing measured in magnetic field units, while A and B refer to hyperfine coupling constants measured in frequency units. Splitting and coupling constants are proportional, but not identical. The book by Wertz and Bolton has more information (pp. 46 and 442). Wertz JE, Bolton JR (1972). Electron spin resonance: Elementary theory and practical applications. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Wertz, John, and James R Bolton. Electron Spin Resonance: Elementary Theory and Practical Application. Chapman and Hall, 1986.

- Goswami, Monalisa; Chirila, Andrei; Rebreyend, Christophe; de Bruin, Bas (2015-09-01). "EPR Spectroscopy as a Tool in Homogeneous Catalysis Research". Topics in Catalysis. 58 (12): 719–750. doi:10.1007/s11244-015-0414-9. ISSN 1572-9028.

- Yashroy RC (1990). "Magnetic resonance studies of dynamic organisation of lipids in chloroplast membranes". Journal of Biosciences. 15 (4): 281–288. doi:10.1007/BF02702669. S2CID 360223.

- YashRoy RC (January 1991). "Protein heat denaturation and study of membrane lipid-protein interactions by spin label ESR". Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods. 22 (1): 55–9. doi:10.1016/0165-022X(91)90081-7. PMID 1848569.

- YashRoy RC (1990). "Determination of membrane lipid phase transition temperature from 13C-NMR intensities". Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods. 20 (4): 353–6. doi:10.1016/0165-022X(90)90097-V. PMID 2365951.

- Chu RD, McLaughlin WL, Miller A, Sharpe PH (December 2008). "5. Dosimetry systems". Journal of the ICRU. 8 (2): 29–70. doi:10.1093/jicru/ndn027. PMID 24174520.

- Kempe S, Metz H, Mader K (January 2010). "Application of electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy and imaging in drug delivery research - chances and challenges". European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 74 (1): 55–66. doi:10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.08.007. PMID 19723580.

- Ikeya M (1993). New Applications of Electron Spin Resonance. doi:10.1142/1854. ISBN 978-981-02-1199-8.

- Bakr MY, Akiyama M, Sanada Y (1990). "ESR assessment of kerogen maturation and its relation with petroleum genesis". Organic Geochemistry. 15 (6): 595–599. Bibcode:1990OrGeo..15..595B. doi:10.1016/0146-6380(90)90104-8.

- Yen, T. F.; Erdman, J. G.; Saraceno, A. J. (1962). "Investigation of the nature of free radicals in petroleum asphaltenes and related substance by electron spin resonance". Analytical Chemistry. 34 (6): 694–700. doi:10.1021/ac60186a034.

- Lovell J, Abdullah D, Punnapala S, Al Daghar K, Kulbrandstad O, Madem S, Meza D (Nov 2020). "A Chemical IoT System for Flow Assurance - From Single-Well Applications to Field Implementation". SPE-203286-MS. ADIPEC. doi:10.2118/203286-MS.

- Khulbe K, Mann R, Lu B, Lamarche G, Lamarche A (1992). "Effects of solvents on free radicals of bitumen and asphaltenes". Fuel Processing Technology. 32 (3): 133–141. Bibcode:1992FuPrT..32..133K. doi:10.1016/0378-3820(92)90027-N.

- Azumi Todaka; Shin Toyoda; Masahiro Natsuhori; Keiji Okada; Itaru Sato; Hiroshi Sato; Jun Sasaki (August 2020). "ESR assessment of tooth enamel dose from cattle bred in areas contaminated due to the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant accident". Radiation Measurements. 136 (106357): 106357. Bibcode:2020RadM..13606357T. doi:10.1016/j.radmeas.2020.106357. S2CID 218993842.

- Nori Nakamura; Yuko Hirai; Yoshiaki Kodama (2012). "Gamma-ray and neutron dosimetry by EPR and AMS, using tooth enamel from atomic-bomb survivors: a mini review". Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 149 (1): 79–83. doi:10.1093/rpd/ncr478. PMID 22267275.

- Gualtieri G, Colacicchi S, Sgattoni R, Giannoni M (July 2001). "The Chernobyl accident: EPR dosimetry on dental enamel of children". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 55 (1): 71–9. Bibcode:2001AppRI..55...71G. doi:10.1016/S0969-8043(00)00351-1. PMID 11339534.

- Chumak V, Sholom S, Pasalskaya L (1999). "Application of High Precision EPR Dosimetry with Teeth for Reconstruction of Doses to Chernobyl Populations". Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 84: 515–520. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a032790.

- S. Toyoda; A. Kondo; K. Zumadilov; M. Hoshi; C. Miyazawa; A. Ivannikov (September 2011). "ESR measurements of background doses in teeth of Japanese residents". Radiation Measurements. 46 (9): 797–800. Bibcode:2011RadM...46..797T. doi:10.1016/j.radmeas.2011.05.008.

- Chauhan, S. K.; et al. (2008). "Detection Methods for Irradiated Foods". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 8: 4. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2008.00063.x.

- Austen, D. E. G.; Given, P. H.; Ingram, D. J. E.; Peover, M. E. (1958). "Electron Resonance Study of the Radicals Produced by Controlled Potential Electrolysis of Aromatic Substances". Nature. 182 (4652): 1784–1786. Bibcode:1958Natur.182.1784A. doi:10.1038/1821784a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- Eaton, Gareth (1998). Foundations of Modern EPR. World Scientific.

- den Hartog, Stephan; Neukermans, Sander; Samanipour, Mohammad; Ching, H. Y. Vincent; Breugelmans, Tom; Hubin, Annick; Ustarroz, Jon (2022-03-01). "Electrocatalysis under a magnetic lens: A combined electrochemistry and electron paramagnetic resonance review". Electrochimica Acta. 407: 139704. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2021.139704. hdl:10067/1857000151162165141. ISSN 0013-4686.

- "Coupled In Situ NMR and EPR Studies Reveal the Electron Transfer Rate and Electrolyte Decomposition in Redox Flow Batteries". doi:10.1021/jacs.0c10650.s001. Retrieved 2024-11-12.

- Webster, R. "Electrochemistry combined with electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy for studying catalytic and energy storage processes. Current Opinion in Electrochemistry". Current Opinion in Electrochemistry. 40: 101308. doi:10.1016/j.coelec.2023.101308.

- ^ EPR of low-dimensional systems

- Krinichnyi VI (1995). 2-mm Wave Band EPR Spectroscopy of Condensed Systems. Boca Raton, Fl: CRC Press.

- Eaton GR, Eaton SS, Barr DP, Weber RT (2010-04-10). Quantitative EPR. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-211-92948-3.

- Eaton GR, Eaton SS, Barr DP, Weber RT (2010). "Basics of Continuous Wave EPR". Quantitative EPR. pp. 1–14. doi:10.1007/978-3-211-92948-3_1. ISBN 978-3-211-92947-6.

- Schweiger A, Jeschke G (2001). Principles of Pulse Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850634-8.

External links

- Electron Magnetic Resonance Program National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (Specialist Periodical Reports) Published by the Royal Society of Chemistry

- Using ESR to measure free radicals in used engine oil

| Spectroscopy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibrational (IR) | |||||||

| UV–Vis–NIR "Optical" | |||||||

| X-ray and Gamma ray | |||||||

| Electron | |||||||

| Nucleon | |||||||

| Radiowave | |||||||

| Others |

| ||||||

| Protein structural analysis | |

|---|---|

| High resolution | |

| Medium resolution | |

| Spectroscopic | |

| Translational diffusion | |

| Rotational diffusion | |

| Chemical | |

| Thermodynamic | |

| Computational | |

| ←Tertiary structureQuaternary structure→ | |

, with magnetic components

, with magnetic components  or

or  . In the presence of an external magnetic field with strength

. In the presence of an external magnetic field with strength  , the electron's magnetic moment aligns itself either antiparallel (

, the electron's magnetic moment aligns itself either antiparallel (

is the electron's so-called

is the electron's so-called  for the free electron,

for the free electron, is the

is the  for unpaired free electrons. This equation implies (since both

for unpaired free electrons. This equation implies (since both  such that the resonance condition,

such that the resonance condition,  , is obeyed. This leads to the fundamental equation of EPR spectroscopy:

, is obeyed. This leads to the fundamental equation of EPR spectroscopy:  .

.

= 0.3350 T = 3350 G

= 0.3350 T = 3350 G

where

where  and

and  depend on the nucleus under study.)

depend on the nucleus under study.)

is the number of paramagnetic centers occupying the upper energy state,

is the number of paramagnetic centers occupying the upper energy state,  is the

is the  is the

is the  ≈ 9.75 GHz) give

≈ 9.75 GHz) give  ≈ 0.998, meaning that the upper energy level has a slightly smaller population than the lower one. Therefore, transitions from the lower to the higher level are more probable than the reverse, which is why there is a net absorption of energy.

≈ 0.998, meaning that the upper energy level has a slightly smaller population than the lower one. Therefore, transitions from the lower to the higher level are more probable than the reverse, which is why there is a net absorption of energy.

) depends on the photon frequency

) depends on the photon frequency

is a constant,

is a constant,  is the sample's volume,

is the sample's volume,  is the unloaded

is the unloaded  is the cavity filling coefficient, and

is the cavity filling coefficient, and  is the microwave power in the spectrometer cavity. With

is the microwave power in the spectrometer cavity. With  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  , where

, where  ≈ 1.5. In practice,

≈ 1.5. In practice,  but also to any local magnetic fields of atoms or molecules. The effective field

but also to any local magnetic fields of atoms or molecules. The effective field  experienced by an electron is thus written

experienced by an electron is thus written

includes the effects of local fields (

includes the effects of local fields ( resonance condition (above) is rewritten as follows:

resonance condition (above) is rewritten as follows:

is denoted

is denoted  and called simply the g-factor, so that the final resonance equation becomes

and called simply the g-factor, so that the final resonance equation becomes

-electron organic radicals, such as the benzene radical anion. The symbols "a" or "A" are used for isotropic hyperfine coupling constants, while "B" is usually employed for anisotropic hyperfine coupling constants.

-electron organic radicals, such as the benzene radical anion. The symbols "a" or "A" are used for isotropic hyperfine coupling constants, while "B" is usually employed for anisotropic hyperfine coupling constants.

is the distance measured from the line's center to the point in which

is the distance measured from the line's center to the point in which  is a distance from center of the line to the point of maximal absorption curve inclination. In practice, a full definition of linewidth is used. For symmetric lines, halfwidth

is a distance from center of the line to the point of maximal absorption curve inclination. In practice, a full definition of linewidth is used. For symmetric lines, halfwidth  , and full inclination width

, and full inclination width  .

.

time.

time.