| Elizabeth Avery Meriwether | |

|---|---|

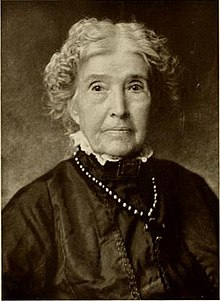

Photo of Elizabeth Avery Meriwether by Takuma Kajiwara Photo of Elizabeth Avery Meriwether by Takuma Kajiwara | |

| Born | Elizabeth Avery (1824-10-19)October 19, 1824 Bolivar, Tennessee, US |

| Died | November 4, 1916(1916-11-04) (aged 92) |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Spouse |

Minor Meriwether (m. 1852) |

Elizabeth Avery Meriwether (January 19, 1824 – November 4, 1916) was an American writer and an activist in the suffrage movement.

Early life

Elizabeth Avery was born in Bolivar, Tennessee, on January 19, 1824. She had two siblings: Nathan Avery and Rebecca Rivers Avery. Her parents moved to Memphis when she was nine years old. She attended school there in a little one-story building, where the principal was teacher and janitor, until twelve years old. After that age her information and knowledge was gained from books and papers, with her father's assistance. With a practical mind and excellent memory she stored up a splendid basis for her future line of literary and lecture work.

Meriwether's father was a physician — Nathan Avery, of New York; her mother, Rebecca Rivers, belonged to one of the old families of Virginia. Her father's ancestors came over with Penn — the founder of Pennsylvania — and were Quakers. After going South he joined the Methodist Church, to which Meriwether belonged. She amusingly related that her own father said grace three times a day before meals, but her Grandfather Rivers said he didn't believe the Lord wanted to be bothered with hearing the same thing so often, so no one was surprised when one day he called the family out to the smokehouse, where the winter's stock of hams and bacon had been cured, and provisions stored for the year, asking them to join him in saying grace over everything at once for the whole year.

Meriwether's parents died when she was a young girl, and she, with two sisters, made their home with their brother, William Thomas Avery, remaining in the old home in Memphis until they married. The two sisters were Amanda Trezevant, four years younger, and Estelle Lamb, six years younger than Meriwether.

Career

She was the author of many books, giving descriptions of historical incidents of importance in the South during and after the war.

For over sixty years she was a steady contributor to the leading newspapers and periodicals of this country.

Her "Travel Letters" caused much favorable comment and interest, and discussions and arguments on political, literary, sociological and every other vital topic of the times, through the columns of the papers, have given her a well-deserved international reputation.

As a lecturer she was the first woman to speak from the platform in the State of Tennessee. With Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and other women in the pioneer field, advocating equal rights for women, she lectured all through New England, Texas and other States. The comments made by the press all over the country about Meriwether as a speaker were always in highest terms — "her natural oratory, keen sarcasm, sparkling wit, earnest and interesting style, glowing eloquence, etc.," were some of the terms used to express her manner of delivery and the enthusiasm she awakened.

The title of one of the books of which she was the author is "Facts and Falsehoods Concerning the War of the South of 1861 and 1865," under a pen name — George Edmonds — which was published in 1904. This Meriwether considered the most valuable book. She said: "If you read this book you will know more about Lincoln than you ever dreamed of."

In 1877 Meriwether wrote a little book entitled "Ku-Klux Klan; or, the Carpet-bagger in New Orleans." An Englishman, then in Memphis, sent a copy of this book to London to the editor of the "Kensington News," who gave it a very complimentary notice, telling her that if she would write a novel and put as much humor and pathos in it as she had put in the little book, "Ku-Klux Klan," he would introduce her to an English publisher who would put it out. She soon had a novel titled "The Master of Red Leaf" ready, and sent it off to London, where the publishers issued a splendid set of three volumes, gilt-edge, etc. An American firm got out a cheaper edition in one volume, paper-bound. This book was sold in Memphis at the rate of 100 copies a week.

"The Sowing of the Swords," in 1910; "My First and Last Love," and "Black and White," 1883, are some of her other stories. Meriwether wrote continuously, and in the end she was busy on her "Recollections of a Long Life."

In post-war Memphis, she became involved with the suffrage movement and the Women's Christian Temperance Union specifically. Despite it being illegal, she both registered and voted in the 1872 presidential election. She presented (unsuccessful) suffrage petitions at both the Democratic and Republican national conventions in 1880.

In 1881 Meriwether began her lecture tour with Susan B. Anthony through the New England States where conventions were being held. Anthony wanted her to speak at these places because she was a Southern woman. As illustrative of her methods of lecturing she carried with her two cartoons, four feet by four feet, which she sketched and painted herself. The men who hated and scorned equal rights declared that no one but an ugly old maid would want to vote, one who could not secure a husband, and should a married woman advocate equal rights she must necessarily be a coarse, rough termagant, who had a feeble-minded, no-account husband. She entered the hall with these cartoons rolled up, and beginning to speak unrolled the old maid's picture, and said, "This is the picture of the woman who failed to get a husband — now in this room is one of our women who has failed to get a husband (pointing to a handsome girl of nineteen), she wants to vote, and this is her picture." The comparison, of course, brought shouts of laughter. Then, unrolling the second cartoon, she explained that it was one of herself, the cartoon represented a rough, coarse woman holding a little scared man under her arm, with his legs dangling, which she said was her husband, although the artist didn't get a good likeness of him, as he was six feet tall. At the time Mrs. Meriwether made those addresses she was a slender, vivacious, attractive young woman, and after comparing her with the cartoon which she said was of herself there was a general roar of laughter, clapping of hands, etc. After putting the audience in a good humor she would deliver the lecture which she had in store for them. The same cartoons are hanging on the wall of her living room now and furnish the material for many interesting anecdotes which she relates with much satisfaction.

The first time Meriwether lectured in Missouri on "equal rights" she received many anonymous letters; in some she was denounced as being everything but a good wife and mother. When she made her first public speech in Tennessee she went to the editor of the paper and wanted him to make the announcement, but he said: "You will have to get the permission of your husband," which, of course, was readily granted; however, Mr. Meriwether expressed his fear that she might become stage-struck, and her son — Lee — a little fellow ten years old, who was lying on the floor, interrupted, "Don't you believe it — mother will go through; she won't get stage struck." The editor, still hoping to discourage her, said people would talk about her. She answered: "They can't say I am not a good wife and mother, or that I get drunk." On the night of the lecture, the hall was crowded to overflowing; she made a very successful address. Her brother, being so afraid she would fail, did not have the courage to attend.

Returning to Memphis after her lecture tour, Meriwether became the editor of a newspaper, "The Tablet." Horace Greeley came to Memphis, making a speech on "Self-Made Men," about that time. Meriwetiier wrote an article which she published in her paper about it — a criticism — a humorous one. She sent a copy of the paper to Horace Greeley, who was the editor of the "New York Tribune," wanting to exchange with him. But he said his exchange list was so long he could not do so, making the suggestion that if she would advertise his paper in "The Tablet" he would send it to her for a year. She replied that if he would print the criticism she had written of him in his paper, she would do so, and send him "The Tablet" for a year. He agreed, and the "Tribune" was sent her for many years.

Personal life

In 1852, she married Minor Meriwether of Kentucky, who became a Confederate Major in Oct. 1861, serving as an Engineer constructing defenses and railroads. During her husband's absence, Elizabeth had to flee with her children from Memphis due to conflict with the Federal forces. She later argued with Union General Hurburt in an effort to regain family property confiscated by the US.

Minor Meriwether never served under Nathan Bedford Forrest during the war, but they knew each other as former Confederate officers and railroadmen. One of the organizational meetings of the Ku Klux Klan took place in her kitchen in the Meriwether's Memphis home, which stood on the site of what is now the Peabody Hotel.

After the war they went back to Memphis, residing there until the yellow fever broke out. Then, going to St. Louis, built the house in which Minor Meriwether died in 1910, and in which Meriwether, with her son, Lee, and his wife, lived till the end. Lee Meriwether, like his father, was an attorney-at-law. He was well known as the author of six books — "A Tramp Trip — How to See Europe on Fifty Cents a Day," published in 1887. This book was regarded as an authority on the subject. Then followed, "The Tramp at Home," 1890; "Afloat and Ashore on the Mediterranean," 1892; "Miss Chunk," 1899; "A Lord's Courtship," 1900, and "Seeing Europe by Automobile," 1911, which was written just twenty-five years after the first book. Lee Meriwether's wife was Jessie M. Gair, of Missouri.

Writings

- The Refugee (Short story - 1863)

- The Master of Red Leaf (1872)

- Black and White (1883)

- The Ku Klux Klan, or The Carpetbagger in New Orleans (1877)

- Facts and Falsehoods About the War on the South (1904) (pseudonym: George Edmonds)

- Sowing of the Swords: The Soul of the Sixties (1910)

Legacy

Meriwether is depicted in a life-size bronze statue in the Tennessee Woman Suffrage Memorial in Market Square in Knoxville, Tennessee, along with Anne Dallas Dudley of Nashville and Lizzie Crozier French of Knoxville. The sculpture is by Alan LeQuire.

References

- ^ Johnson, Anne (1914). Notable women of St. Louis, 1914. St. Louis, Woodward. p. 153. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Parsons, Elaine Frantz. Manhood Lost: Fallen Drunkards and Redeeming Women in the Nineteenth-Century United States, Baltimore: JHU Press, 2010.

- Tennessee Woman's Suffrage Memorial Archived 2007-07-07 at the Wayback Machine website, accessed April 6, 2010

External links

- Elizabeth Avery Meriwether listing in the Tennessee Encyclopedia

- Elizabeth Avery Meriwether on RootsWeb