A writ of coram nobis (also writ of error coram nobis, writ of coram vobis, or writ of error coram vobis) is a legal order allowing a court to correct its original judgment upon discovery of a fundamental error that did not appear in the records of the original judgment's proceedings and that would have prevented the judgment from being pronounced.

In the United Kingdom, the common law writ is superseded by the Common Law Procedure Act of 1852 and the Criminal Appeal Act 1907.

The writ survives in the United States in federal courts, in the courts of sixteen states, and the District of Columbia courts. Each state has its own coram nobis procedures. A writ of coram nobis can be granted only by the court where the original judgment was entered, so those seeking to correct a judgment must understand the criteria required for that jurisdiction.

Terminology

A writ is an official written command, while a writ of error provides a superior court the means to correct errors of a lower court. A writ of error coram nobis is a variation of the writ of error providing a court with the means to correct its own errors. "Coram nobis" is Latin for "before us". Initially, when the Lord Chancellor issued orders on behalf of the King and the royal court, the word "us" simply referred to the King, the Lord Chancellor, and other judges of the royal court. The meaning of its full form, quae coram nobis resident, is "which remain in our presence".

Over time, the authority to issue writs shifted from the Lord Chancellor to the courts. Although the King was no longer part of the court issuing the writ, the name "coram nobis" continued because courts associated the name with its function rather than its original Latin meaning. Thus, in English law, the definition of "coram nobis" evolved and is now redefined as a remedy for a court to correct its own error.

History

The writ of coram nobis originated in the courts of common law in the English legal system during the sixteenth century. The writ of coram nobis still exists today in a few courts in the United States, where it applies only to criminal proceedings, not civil ones.

Common law

In English common law, a "petition of error" requested higher courts to review the legality of an order or sentence (similar to what is now known as an appeal). The writ of error was an original writ which began a legal proceeding (other writs were issued during proceedings). Petitioners brought a petition of error before the Lord Chancellor. If a lower court committed an error of law, the Lord Chancellor would issue a writ of error. A writ of error required the lower court to deliver the "record" of the case to a superior court where the court reviewed the case for legal errors. Because a writ of error was only available for a higher court to determine if a lower court committed an error of law, courts needed another type of writ to correct its own decision upon an error of fact. To rectify this issue, the Lord Chancellor created a new writ - the writ of error coram nobis. Thus, the original writ of coram nobis provided the means to correct errors that the writ of error could not correct. Unlike the writ of error, the writ of coram nobis:

- corrected only factual errors that were not raised in the original case proceedings,

- allowed the same court that presided over the original case to correct its own error, and

- required the original case records to remain with the court that presided over the original case.

Abolition in English courts

The first case involving the writ of coram nobis is unknown due to incomplete historical records prior to the sixteenth century; however, the first recorded case involving the writ of coram nobis occurred in 1561 in the case of Sir Gilbert Debenham and Another v. Bateman.

Until 1705, the writ of error was originally a matter entirely up to the discretion of either the monarch or those with the authority to make decisions on behalf of the monarch; but in 1705, the court held that the writ was a matter of right instead of a matter of discretion. Despite making writs of error a matter of right, courts rarely used these writs because of their cumbersome and impractical procedure. A writ of error moved the record from the original court to a higher court; however, the record only contained information on the arraignment, the plea, the issue, and the verdict. The record did not include the most material parts of a trial, including the evidence and the judge's direction to the jury.

As a result, England abolished all writs of error, including the writs of coram nobis and coram vobis, and replaced them with appellate procedures encompassing all rights previously available through these writs. Thus, the abolition of the writ of coram nobis in England was due mostly to administration difficulties with the writ of error, and not because of administration difficulties with the writ of coram nobis itself.

The law abolishing the writ in civil cases was the Common Law Procedure Act 1852. The law abolishing the writ in criminal cases was the Criminal Appeal Act 1907.

United States

After arriving in North America in the seventeenth century, English settlers established English colonies. Within these colonies, the settlers created colonial courts that adhered to the English legal system and issued writs in the same manner as English courts. After the United States obtained independence from England, state governments, as well as the federal government, provided courts the authority to continue to rely upon writs as a source of law unless issuing the writ violated the state or federal constitution or if either the state or federal government subsequently enacted a statute restricting the writ. The purpose of allowing courts to issue writs was to fill a void whenever the state constitution, state statutes, the U.S. Constitution or federal statutes did not address an issue to be decided before the court. Writs were especially important when the federal government, as well as each state, first established its judicial system. During those times, there were very few (if any) statutes or case laws for courts to rely upon as guidance. In those circumstances, the English writs provided fledgling federal and state courts an important source of law. Over time, writs became significantly less important as Congress and state legislatures enacted more statutes and further defined rules for its judiciary. Writs also evolved independently in the federal judicial system and each state's judicial system so that a writ within one judicial systems may have a vastly different purpose and procedures from the same writ in other judicial systems. Different characteristics of a writ from one judicial system to another is the result of the federal system of government prescribed within the United States Constitution. Federalism in the United States is a mixed system of government that combines a national federal government and state governments. While federal courts are superior to state courts in federal matters, the Constitution limits the reach of federal courts; thereby, providing state courts general sovereignty and law-making authority over a wider range of topics. This sovereignty allows each judicial system to decide whether to adopt writs and the function and purpose of each writ it adopts. Thus, the use and application of writs, including the writ of coram nobis, can vary within each of these judicial systems.

Legislation authorizes a judicial system to issue the writ of coram nobis under one of two conditions:

- Where legislation permits courts to issue writs, but the legislation does not specifically mention the writ of coram nobis. Courts throughout the United States generally have the authority to issue writs whenever the constitution or statutes encompassing a court's jurisdiction do not address an issue before the court and issuance of the writ is necessary to achieve justice. This authority was especially important for earlier courts when there were few statutes or case law to rely upon. Over time, legislatures enacted statutes encompassing almost all issues that could arise before a court. As a result, courts today rarely need to rely on writs as a source of law to address an issue not covered by statute. One example of a rare issue where courts have the occasion to issue the writ of coram nobis is the issue of former federal prisoners who have new information and this new information would have resulted in a different verdict if the information were available at the time of trial. Whenever this specific issue comes before a federal court, there is no federal statute that specifically guides or regulates how the court must proceed; however, federal courts have determined that the writ of coram nobis is the proper vehicle to achieve justice under this specific issue.

- Where legislation specifically permits courts to issue, by name, the writ of coram nobis. The use of writs in the United States is more common when legislation has authorized a writ by name and regulated its use by courts. For earlier courts, the practice of issuing writs was an integral part of the judicial system's proceedings. Therefore, when legislatures enacted laws to regulate issues associated with writs, some legislatures adopted the exact name of the writ within its rules while other legislatures chose to abolish the names of the writ but provided an alternative remedy under a different name. Tennessee is an example of a state where its legislature enacted a statute expressly authorizing courts to issue, by name, the "Writ of Error Coram Nobis" and regulated how this writ should be issued. In contrast, other states replaced the writ of coram nobis with other post-conviction remedies. For example, the Pennsylvania legislature enacted a law on January 25, 1966, that expressly abolished the name "writ of coram nobis" and enacted the state's Post Conviction Relief Act, which is now the sole means for obtaining post-conviction relief.

Coram nobis in United States federal courts

In 1789, Congress passed the Judiciary Act to establish the judicial courts in the United States. This Act also allows courts to issue writs, including the writ of coram nobis. Originally, federal courts applied the writ of coram nobis only to correct technical errors, such as those made by a clerk of the court in the records of the proceedings. The 1914 Supreme Court case United States v. Mayer expanded the scope of the writ of coram nobis to include fundamental errors, but the Court declined in this case to decide whether federal courts are permitted to issue the writ of coram nobis. In 1954, the Supreme Court determined in United States v. Morgan that federal courts are permitted to issue the writ of coram nobis to correct fundamental errors, such as those where discovery of new information is sufficient to prove a convicted felon is actually innocent. Since the Morgan case, federal courts traditionally issue a writ of coram nobis whenever a former federal prisoner petitions the original sentencing court to set aside the conviction based upon new information that was not available when the petitioner was in custody and where this new information demonstrates that the conviction was a result of a fundamental error.

History of the writ of coram nobis in federal courts from 1789 to 1954

The Judiciary Act of 1789

The history of the writ of coram nobis in United States federal courts began in 1789 when Congress enacted the Judiciary Act. Under Section 14 of the Judiciary Act, federal courts have the authority to issue a writ whenever the court deems it necessary to achieve justice and whenever no congressional law covers the issues before the court. This section was known as the "All-Writs Provision" of the Judiciary Act until 1948 when it became more commonly known as the "All-Writs Act" after Congress modified the Judicial Code and consolidated this provision into 28 U.S.C. § 1651. Under the All Writs Act, federal district courts have the "power to issue writs of scire facias, habeas corpus, and all other writs not specifically provided for by statute". Congress had not specifically provided by statute the authority for federal courts to issue a writ of coram nobis; therefore, the All Writs Act provides federal courts this authority.

The first case in a federal court to address the writ of coram nobis was Strode v. The Stafford Justices in 1810. In this case, the Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall wrote the opinion in this Circuit Court case and held that the writ of coram nobis is distinguishable from the writ of error and therefore not subject to the writ of error's statute of limitations. The first Supreme Court case mentioning the writ of coram nobis (using the term coram vobis) is the 1833 case, Pickett's Heirs v. Legerwood. In this case, the Court determined that the writ was available to correct its own errors, but the same remedy was also available using the preferred method of submitting a motion to the court. Eighty years later, in 1914, the Supreme Court reached a similar conclusion in United States v. Mayer. Thus, while federal courts confirmed the writ of coram nobis was available to federal courts, this remedy was rarely necessary or appropriate in federal courts throughout the nineteenth century for the following two reasons:

- Courts generally considered the writ of coram nobis to be restricted to correct only technical errors, such as discovery of a defendant being under age, evidence that a defendant died before the verdict, or errors made by the court clerk in the recording of the proceedings.

- Petitioners could raise a "motion to amend" to correct most of errors also corrected by the writ of coram nobis. Although courts recognized that the writ of coram nobis could also reverse the judgement on such defects, the preferred practice was to present the court with a motion to amend.

1946 amendments to the Rules of Civil Procedure

In 1946, Congress amended the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and specifically abolished the writ of coram nobis in federal civil cases. Prior to enactment of these amendments, Congress reviewed all relief previously provided for civil cases through the writ of coram nobis and adopted those avenues of relief into the rules; therefore, eliminating the need for the writ in federal civil cases. In the amendment, Congress expressly abolished the writ of coram nobis in Rule 60(b). Later, in 2007, Congress restructured the format of Rule 60, and moved the language expressly abolishing the writ of coram nobis in civil proceedings from Rule 60(b) to Rule 60(e) in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

History of post-conviction remedies available to former federal prisoners from 1789 to 1954

Post-conviction remedies for former federal prisoners prior to 1867

In 1790, one year after Congress passed the Judiciary Act establishing federal courts, Congress enacted the Crimes Act which created the first comprehensive list of federal offenses. From 1790 until 1867, there are few, if any, records of individuals challenging a federal criminal conviction after completion of the prison sentence. Two primary reasons explain the absence of any challenges to a conviction by former federal prisoners:

- The Crimes List provided only twenty-three federal crimes. Seven of these crimes, including treason and murder, were punishable by death. (In comparison, today there are approximately 3,600 to 4,500 federal statutes that impose criminal punishments.) There are an estimated 500,000 former federal prisoners. Despite this large population, recent cases where a former federal prisoner is able to find new information sufficient to reverse the conviction are exceedingly rare. Thus, the chances of this type of case arising prior to 1867, when the federal prison population was significantly smaller, are even more remote.

- There were few collateral consequences stemming from a conviction at this time. Generally, the reason former convicted felons seek a writ of coram nobis is to eliminate collateral consequences ensuing the challenged conviction. Collateral consequences are indirect consequences of a conviction. While direct consequences of a conviction are usually issued by a judge in the sentencing phase of a case (such as a prison sentence, probation, fines and restitution); indirect consequences of a conviction are not contained within a court sentence. Collateral consequences may include loss of voting privileges, loss of professional licenses, inability to qualify for some employment and housing opportunities, and damage to the person's reputation.

The Habeas Corpus Act of 1867

The American Civil War is historically significant upon the rights of former federal prisoners in two ways. First, Congress enacted the Habeas Corpus Act of 1867 to prevent abuses following the civil war. This Act expanded the writ of habeas corpus to any person, including former prisoners. Second, states began imposing more collateral consequences upon those convicted of crimes; thus, providing more reasons why a person would want to have a wrongful conviction overturned. The loss of voting privileges was one of the most significant collateral consequences of a felony conviction. In 1800, no state prohibited convicted felons from voting; but by end of the U.S. Civil War, nearly 80% of state legislatures had passed laws barring felons the right to vote.

Slavery was legal in the United States until the 1860s. In the 1860 U.S. presidential election, Republicans, led by Abraham Lincoln, supported the elimination of slavery. This controversial issue was the catalyst for the American Civil War that began in 1861 following the election of Lincoln and concluded in 1865. On March 3, 1865, President Lincoln signed a joint resolution declaring wives and children of persons in the armed forces to be free; and on December 18, 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution became effective. This Amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States. The purpose of the Habeas Act was to provide "what legislation is necessary to enable the courts of the United States to enforce the freedom of the wife and children of soldiers of the United States, and also to enforce the liberty of all persons".

The Habeas Corpus Act of 1867 expanded the jurisdiction of the writ of habeas corpus to "any person". One year later, the Supreme Court implied that this Act had no custody requirements. The Court said the Act "is of the most comprehensive character. It brings within the habeas corpus jurisdiction of every court and of every judge every possible case of privation of liberty contrary to the National Constitution, treaties, or laws. It is impossible to widen this jurisdiction." The Court's interpretation of this act seemed to eliminate the writ of coram nobis in criminal cases because any person challenging a conviction, regardless of whether the person is in prison or not, could have raised the claim through the writ of habeas corpus.

Although the Act expanded habeas jurisdiction to "any person", it also required that an application for the writ include "facts concerning the detention of the party applying, in whose custody he or she is detained". In 1885, the Supreme Court read these application requirements as an intent by Congress to restrict the writ of habeas corpus to only those who were physically restrained in jail. Thus, the Court foreclosed the writ of habeas corpus to those no longer in custody.

United States v. Morgan (1954) provides writ of coram nobis to former federal prisoners

In 1948, Congress passed legislation that would lead to the official recognition of the writ of coram nobis in federal courts. The Act of June 25, 1948 combined two pieces of legislation:

- Congress passed the Act to organize all laws of the United States into a single source of reference, known as the United States Code (abbreviated U.S.C.). Any law (or statute) ever passed by Congress can be found in the United States Code. The U.S.C. is divided into 50 titles. Within each title is a chapter, and within each chapter is a section. For example, one of the titles created in the Act was Title 28 – Judiciary and Judicial Procedure. Chapter 153 of this title is the chapter on Habeas Corpus. Section 2255 of this title is the section providing how prisoners can challenge a conviction. In legal documents, this section is commonly abbreviated 28 U.S.C. §2255.

- Congress passed the Act to solve a problem with habeas corpus petitions. The Habeas Corpus Act of 1867 instructed prisoners to file a writ of habeas corpus with the district court whose territory included the prison. For example, those imprisoned at Alcatraz Island, California were required to file a writ of habeas corpus in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, even if the prisoner's conviction and sentence originated from a federal court in another district or state. This rule led to administrative difficulties, especially for the five district courts whose territorial jurisdiction included major federal prisons. The Act of June 25, 1948 codified existing federal habeas corpus statutes and judicial habeas practice at 28 U.S.C. §2255 and changed the jurisdiction from the district of confinement to the district of sentence; however, the jurisdictional change was the only change Congress intended.

The Act of June 25, 1948 reworded the habeas corpus sections of the United States Code to provide only those individuals in custody (as a result of a criminal conviction in federal court) access to the writ of habeas corpus. For those who had been convicted of a federal crime but were no longer in custody, the question was whether the 1948 Act abolished all post-conviction review of a former prisoner's conviction.

In 1952 Robert Morgan, a former federal prisoner who had completed his sentence, petitioned to have his conviction overturned based on information he claimed to be unavailable at the time of his conviction. The district court denied his petition because Morgan was no longer in custody for the conviction he sought to overturn. Morgan appealed that decision. In 1953, the appellate court disagreed with the district court and determined that the writ of coram nobis was available to Morgan. The government appealed the appellate court's decision to the US Supreme Court.

The first question in United States v. Morgan was whether Congress intended to abolish any post-conviction remedies to former prisoners when it restricted the writ of habeas corpus to prisoners only. If the Supreme Court decided that Congress did not intend to abolish any post-conviction remedies to former prisoners, then the second question in United States v. Morgan was whether the writ of coram nobis was available to challenge a conviction after completion of the petitioner's sentence. On January 4, 1954, the Supreme Court announced its decision. The Court first determined that Congress did not intend within the 1948 Act to eliminate all reviews of criminal convictions for petitioners who had completed their sentence. Although the 1948 Act restricted former prisoners from challenging a conviction with a writ of habeas corpus, the Court determined by reviewing the legislative notes that Congress did not intend to abolish post-conviction challenges to a sentence from former prisoners. Justice Stanley Reed, who authored the majority opinion for the Court, wrote;

he purpose of § 2255 was "to meet practical difficulties" in the administration of federal habeas corpus jurisdiction. ... Nowhere in the history of Section 2255 do we find any purpose to impinge upon prisoners' rights of collateral attack upon their convictions. We know of nothing in the legislative history that indicates a different conclusion. We do not think that the enactment of § 2255 is a bar to this motion, and we hold that the District Court has power to grant .

Although Congress did restrict the writ of habeas corpus to prisoners, the Court determined that the All Writs Act provides federal courts the authority to issue a writ of coram nobis to former prisoners whenever new evidence proves the underlying conviction was a result of a fundamental error. Thus, Morgan officially recognized the writ of coram nobis as the sole means for post-incarceration judicial review of federal convictions.

Source of rules and procedures governing coram nobis proceedings

United States v. Morgan provides broad, general guidance to courts on the rules and procedures in coram nobis proceedings, but since the Morgan case in 1954, the Supreme Court and Congress seldom provide lower courts additional guidance. Thus, Appellate courts generally fill in the gaps and provide guidance for rules and procedures unclarified by Congress and the Supreme Court; however, the interpretations of rules and procedures of coram nobis may differ in each appellate court. Thus, for a former federal prisoner who is attempting to decide whether to file a petition for the writ of coram nobis, it is necessary to understand the source of the rules and procedures.

The United States Constitution is the supreme law of the United States. Article One of the Constitution creates the legislature and provides Congress the means to create and enact laws. Article Three of the Constitution creates the judiciary and provides courts the means to interpret laws. Other than the writ of habeas corpus, the Constitution has no language permitting or restricting courts from issuing specific writs, including the writ of coram nobis.

Congressional enactments

The United States Congress enacts laws or statutes, and codifies these statutes in the United States Code. In contrast to the writ of habeas corpus, Congress has seldom enacted statutes regulating the writ of coram nobis. Statutes enacted by Congress regulating the writ of coram nobis are:

- In 1789, Congress enacted the Judicial Act. The All Writs Act section of the Judiciary Act provides federal courts the authority to issue "all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law". The All Writs Act gives courts the ability to decide which specific writs utilized in English courts are available and appropriate in U.S. federal courts. While Congress provides federal courts the authority to issue writs, it does not provide courts the authority to issue specific writs by name, such as writs of mandamus or writs of coram nobis. The code for the All Writs Act is 28 U.S.C. § 1651.

- In 1946, Congress amended the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to abolish the writ of coram nobis in federal civil cases. Prior to enacting this statute, Congress reviewed all issues previously addressed by federal courts in writ of coram nobis proceedings, and incorporated remedies for those issues within the procedures. Rule 60(e) of this Procedure originated from this statute and states, "The following are abolished: bills of review, bills in the nature of bills of review, and writs of coram nobis, coram vobis, and audita querela."

- In 2002, Congress enacted Rule 4(a)(1)(C) of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure to resolve a conflict among the federal appellate courts regarding the time limitations to file an appeal from an order granting or denying an application for a writ of error coram nobis. Prior to this amendment, the federal appellate courts were divided on whether coram nobis appeals have a 10-day time limit or a 60-day time limit. Rule 4(a)(1)(C) resolved the conflict and established a 60-day time limit to file the notice of appeal from a district court's judgement in a coram nobis proceeding.

United States Supreme Court decisions

Following the Constitution and Congressional statutes, the next highest source for direction and guidance of rules and procedures is the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court is the highest federal court. Lower courts, such as federal appellate courts and federal district courts, must follow the decisions of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has discretionary appellate jurisdiction, meaning the Court chooses to hear cases for reasons it deems "compelling reasons" (such as resolving a conflict in the interpretation of a federal law or resolving an important matter of law). Federal courts, including the Supreme Court, cannot override any law enacted by Congress unless the law violates the Constitution. Federal courts also cannot repeal a statute unless Congress clearly intended to repeal the statute. In 1954, United States v. Morgan provides writ of coram nobis to former federal prisoners. The Court determined coram nobis relief "should be allowed ... only under circumstances compelling such action to achieve justice". Specifically, the circumstances must include all three of these conditions:

- to remedy errors "of the most fundamental character"

- when "no other remedy then available"

- "sound reasons for failure to seek appropriate earlier relief".

Since 1954, the Supreme Court granted review of only one other coram nobis case. In 2009, the Court clarified that Article I military courts have jurisdiction to entertain coram nobis petitions to consider allegations that an earlier judgment of conviction was flawed in a fundamental respect. Other than providing military courts the authority to issue the writ, the Supreme Court has declined to provide federal courts additional guidance in coram nobis proceedings. Appellate courts have occasionally criticized the Supreme Court for failing to provide this additional guidance. The Seventh Circuit called the writ of coram nobis, "a phantom in the Supreme Court's cases" and contends "Two ambiguous decisions on the subject in the history of the Supreme Court are inadequate." The Sixth Circuit took a similar stance saying, "The Supreme Court has decided only one coram nobis case in the last forty-two years, Morgan, and that opinion is ambiguous concerning whether proof of an ongoing civil disability is required." The First Circuit wrote that its decision of time limitations "derives from the Morgan Court's cryptic characterization of coram nobis as a 'step in the criminal case'". In another case, the First Circuit writes, "The metes and bounds of the writ of coram nobis are poorly defined and the Supreme Court has not developed an easily readable roadmap for its issuance."

Federal courts of appeals decisions

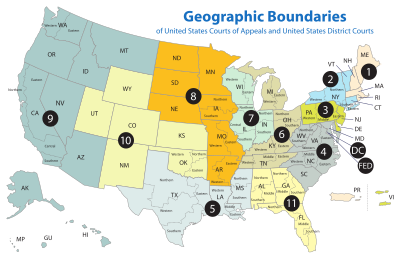

While the United States Supreme Court is the highest court in the United States federal court system, the United States courts of appeals, or circuit courts, are the intermediate appellate courts. There are thirteen U.S. courts of appeals. Eleven courts of appeals are numbered First through Eleventh and have geographical boundaries of various sizes. For example, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals consists of all federal courts in only three states: Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas, while the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals consists of nine western states and two U.S. territories. There is also a Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia and a Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Other tribunals also have "Court of Appeals" in their titles, such as the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, which hears appeals in court-martial cases.

Congressional statutes and Supreme Court decisions are controlling over courts of appeals. Absent statutory rules or Supreme Court case law, a court of appeals decision establishes a binding precedent for the courts in its circuit; however, a court of appeals decision is not binding for courts in other circuits. Generally, when a court of appeals hears an issue raised for the first time in that court, it arrives at the same conclusion as other courts of appeals on identical issues raised before those courts. However, whenever the courts of appeals arrive at different conclusions on the same issue, it creates a "circuit split". The Supreme Court receives thousands of petitions each year, but only agrees to hear fewer than 100 of these cases. One of the most compelling reasons for the Supreme Court to accept a case is to resolve a circuit split. Currently, a circuit split exists in coram nobis cases involving the definition of "adverse consequences". The Supreme Court determined in United States v. Morgan that a petition for a writ of coram nobis must demonstrate that adverse consequences exist from the criminal conviction. Some courts of appeals determined adverse consequences occur with any collateral consequence of a conviction while other courts of appeals have limited "adverse consequences" to only a few collateral consequences of a conviction.

Federal district court decisions

District courts must abide by congressional statutes, Supreme Court decisions, and decisions of the court of appeals in the federal judicial circuit in which the district court is located. Whenever a district court hears an issue that is not specifically addressed by statute or by case law of a higher court, district courts often "develop the record". In case of an appeal, the higher courts have the district court's reasoned decision as guidance. A developed record not only greatly facilitates the process of appellate review but also ensures that the district court has carefully considered the issues and applied the applicable law.

Criteria for the writ

Rules for petitioners

Writs of coram nobis are rare in U.S. federal courts due to the stringent criteria for issuance of the writ. Morgan established the following criteria required in a coram nobis petition in order for a federal court to issue the writ:

- A petition for a writ of coram nobis is a collateral attack on a judgment in a federal criminal case. A "collateral attack" is defined as an attack on a judgment in a proceeding other than a direct appeal. Fourth Appellate, Orange County Ca, Division 3. Ronald Regan Federal Building, pending accurate information to file petition to overturn conviction in which completed reports from law enforcement were not presented prior to sentencing. discovery report was available prior to retaining private counsel. Prejudice was a factor, lack of training and knowledge. Reg E included adversely with no Forensics, poor delegation, am inaccurate deflection of character. Eighth Amendment violation, Human Trafficked through Mental Court, in custody 1 year.

- Breach of Contract Future proceedings, Airbag allegations.

- A petition for a writ of coram nobis in a federal court must seek to vacate a federal criminal conviction. A writ of coram nobis is not available in federal courts to challenge a conviction in a state court. The federal government operates its own coram nobis procedures independent from state courts. Those seeking to attack a state judgment must follow the post-conviction remedies offered by that state. A writ of coram nobis is also not available for civil cases. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b) specifically abolished the writ of coram nobis in civil cases.

- A petition for a writ of coram nobis may only be filed after a sentence has been served and the petitioner is no longer in custody. A person who is on probation is considered "in custody". Anyone filing a coram nobis petition while in custody will have their petition either denied for lack of jurisdiction or categorized as a petition for a writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2255 (or successive 28 U.S.C. § 2255 if the petitioner has previously filed a § 2255 petition).

- A petition for a writ of coram nobis must be addressed to the sentencing court. To challenge a conviction, the petitioner must send a request for a writ of coram nobis to the court clerk of the district court where the petitioner's conviction originated. In other words, a petitioner must request for the writ in the sentencing court, rather than any convenient federal court.

- A petition for a writ of coram nobis must provide valid reasons for not attacking the conviction earlier. Petitioners need to show "reasonable diligence", where legitimate justifications exist for not raising challenges to their convictions sooner or through more usual channels (such as a § 2255 petition while in custody). A delay may be considered reasonable when the applicable law was recently changed and made retroactive, when new evidence was discovered that the petitioner could not reasonably have located earlier, or when the petitioner was improperly advised by counsel not to pursue habeas relief.

- A petition for a writ of coram nobis must raise new issues of law or fact that could not have been raised while the petitioner was in custody. In Morgan, the Court announced the writ was available where no other remedy is available. However, petitioners occasionally misinterpret this statement as an opportunity to re-raise arguments from previous post-conviction petitions. Appellate courts have consistently determined that the writ of coram nobis cannot be used as a "second chance" to challenge a conviction using the same grounds raised in a previous challenge.

- Petitioners who filed a § 2255 motion and it was denied while in custody must obtain authorization from the district court in order to file a coram nobis petition. Currently, this rule only applies to those in the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. In 2018, the Eighth Circuit became the first appellate court to decide whether a petition for writ of coram nobis is governed by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 ("AEDPA") restrictions on successive relief as defined in § 2255(h)(1) and (2). The Eighth Circuit held that coram nobis petitioners who filed a § 2255 motion, while in custody and the motion was denied while the petitioner remained in custody, is restricted by AEDPA from filing a coram nobis petition without first obtaining authorization from the district court to file the coram nobis petition. This requirement is different from those in custody who are required to obtain authorization from the appellate court in order to file a successive § 2255 motion. Other federal appellate courts have yet to issue an opinion on this question.

- A petition for a writ of coram nobis must provide adverse consequences which exist from the conviction. A circuit split exists on this requirement. The First, Second, Third, Fifth, Seventh, Eighth, and Tenth circuit courts administer a "civil disabilities test" which requires a coram nobis petitioner to prove that his conviction produced ongoing collateral consequences; however, the Fourth, Ninth and Eleventh Circuits have held that the petitioner need not show that he is suffering from an ongoing "civil disability" because "collateral consequences flow from any criminal conviction". The Sixth circuit has granted coram nobis relief without mentioning this requirement.

- The writ of coram nobis is an extraordinary remedy to correct errors of the most fundamental character. The error to be corrected must be an error which resulted in a complete miscarriage of justice. In other words, the error is one that has rendered the proceeding itself irregular and invalid. Typically, the same errors that are deemed grounds for Section 2255 habeas relief also justify coram nobis relief. For those claiming actual innocence, a fundamental miscarriage of justice occurs where a constitutional violation has resulted in the conviction of one who is actually innocent.

Procedural rules in federal district courts

- District court clerks should file petitions for writs of coram nobis under the original case number In Morgan, the Supreme Court provided that the writ of coram nobis is a step in the criminal case and not the beginning of a separate civil proceeding. As a result, district courts, such as those in the Ninth Circuit, file petitions for writs of coram nobis under the original criminal case number.

- District courts should construe incorrectly titled petitions with the appropriate title. Whenever a federal district court receives an incorrectly labeled or incorrectly titled petition, the court should construe the petition correctly. District courts should construe a coram nobis petition from a federal prisoner as a petition for writ of habeas corpus. Similarly, district courts should construe a habeas corpus petition from a former federal prisoner as a petition for writ of coram nobis. Federal courts have determined that a person on probation is still a federal prisoner; therefore, petitioners in this category must file a petition for writ of habeas corpus. A federal prisoner convicted of more than one federal crime may file a petition for writ of coram nobis to challenge any conviction where the sentence is complete; but the prisoner must file a writ of habeas corpus to challenge any conviction where the sentence is not complete.

Procedural rules in federal appellate courts

- Appeals from coram nobis orders are subject to a 60-day filing period. Until 2002, two provisions in Morgan divided the federal appellate courts interpretation on the time limits to file an appeal from a district court's decision on a coram nobis petition. First, Morgan held that "the writ of coram nobis is a step in the criminal case". Second, Morgan held that "the writ of coram nobis is of the same general character as the writ of habeas corpus". This created a conflict in the courts of appeals regarding the time limits that applied to appeals from coram nobis orders. In 2002, Congress added language to the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure that clarified an application for a writ of error coram nobis is subject to a 60-day filing period.

- Appeals from coram nobis orders do not require a certificate of appealability. In 1996, Congress enacted the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 ("AEDPA") which included language that limits the power of federal judges to grant motions for habeas relief, including motions for relief pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2255. AEDPA requires a Certificate of Appealability in order to appeal a district court's ruling on a habeas corpus petition. Unlike the writ of habeas corpus, a Certificate of Appealability is not required in order to appeal a district court's ruling on a coram nobis petition. Neither the 28 U.S.C. § 1651(a) statute making the writ of coram nobis available in federal courts in criminal matters nor any Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure requires a certificate of appealability before an appeal may be taken, nor does such a requirement appear in the case law. Some prisoners have attempted to file coram nobis petitions if AEDPA prevents the petitioner from filing under § 2255. However, federal courts have consistently held that prisoners may not resort to the writ of coram nobis in order to bypass AEDPA's gatekeeping requirements.

- The standard of review from a district court's denial of a coram nobis petition is similar to the standard of review from a district court's denial of a habeas corpus petition. Generally, the standard of review is that any district court's determinations on questions of law are reviewed de novo, but that district court's determinations on questions of fact are reviewed for clear error (or clearly erroneous error). Under de novo review of federal coram nobis cases, the appellate court acts as if it were considering the question of law for the first time, affording no deference to the decision of the district court. Under Clear Error review of federal coram nobis cases, the appellate court must have a "definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been committed" by the district court.

U.S. state courts

Only sixteen state courts and District of Columbia courts recognize the availability of writs of coram nobis or coram vobis. Each state is free to operate its own coram nobis procedures independent of other state courts as well as the federal court system. The writ of coram nobis is not available in a majority of states because those states have enacted uniform post-conviction acts that provide a streamlined, single remedy for obtaining relief from a judgment of conviction, and that remedy is available to petitioners who are no longer in custody. States that have replaced writs of coram nobis with remedies within their post-conviction proceedings are also independent of other state courts as well as the federal court system. These proceedings enacted by state legislatures may either be more or less stringent than the writs it replaced or the post-conviction proceedings of other states.

Availability

The following table provides whether each state's courts are authorized to issue a writ of coram nobis (or a writ of coram vobis), or provides the state statute which replaced or abolished the writ.

| State | Writ of coram nobis replaced/abolished by |

|---|---|

| Alabama | Coram nobis recognized by Alabama state courts |

| Alaska | Alaska Criminal Rule 35.1 |

| Arizona | Arizona Rules of Criminal Procedure 32.1 |

| Arkansas | Coram nobis recognized by Arkansas state courts |

| California | Coram nobis recognized by California state courts |

| Colorado | Colorado Rules of Criminal Procedure 35 |

| Connecticut | Coram nobis recognized by Connecticut state courts |

| Delaware | Delaware Superior Court Criminal Rule 61 |

| District of Columbia | Coram nobis recognized by District of Columbia courts |

| Florida | Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.850 |

| Georgia | Official Code of Georgia Annotated § 5-6-35 (a) (7) |

| Hawaii | Hawaiʻi Rules of Penal Procedure Rule 40(a)(1) |

| Idaho | Idaho Code Annotated § 19-4901 |

| Illinois | Illinois Code of Civil Procedure § 2-1401 |

| Indiana | Indiana Rules of Post-Conviction Procedure § 1 |

| Iowa | Iowa Code Annotated § 822.1 |

| Kansas | Kansas Statutes Annotated 60-260 |

| Kentucky | Kentucky Rules of Civil Procedure CR 60.02 |

| Louisiana | Louisiana Code of Criminal Procedure Art. 930.8 |

| Maine | Maine Revised Statutes 15 § 2122, 2124 |

| Maryland | Coram nobis recognized by Maryland state courts |

| Massachusetts | Massachusetts Rules of Criminal Procedure Rule 30 (a) |

| Michigan | Michigan Court Rules 6.502(C)(3) |

| Minnesota | Minnesota statute. § 590.01 subd. 2 |

| Mississippi | Mississippi Code Annotated section 99-39-3(1) |

| Missouri | Missouri Rules of Criminal Procedure Rule 29.15 |

| Montana | Montana Code Annotated § 46–21-101 |

| Nebraska | Coram nobis recognized by Nebraska state courts |

| Nevada | Coram nobis recognized by Nevada state courts |

| New Hampshire | Coram nobis recognized by New Hampshire state courts |

| New Jersey | New Jersey Court Rule 3:22 |

| New Mexico | New Mexico Rules Annotated Rule 1-060(B)(6) |

| New York | Coram nobis recognized by New York state courts |

| North Carolina | North Carolina General Statutes § 15A-1411 (2009) |

| North Dakota | North Dakota Century Code § 29–32.1-01 (2006) |

| Ohio | Ohio Revised Code Annotated § 2953.21 |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma Statutes Title 22, § 1080 |

| Oregon | Coram nobis recognized by Oregon state courts |

| Pennsylvania | Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes 42 § 9542 |

| Rhode Island | Rhode Island General Laws § 10–9.1-1 (2012) |

| South Carolina | South Carolina Code of Laws Annotated § 17-27-20 (2003) |

| South Dakota | Coram nobis recognized by South Dakota state courts |

| Tennessee | Coram nobis recognized by Tennessee state courts |

| Texas | Texas Code of Criminal Procedure article 11.05 |

| Utah | Utah Code Annotated §§ 78B-9-102, -104 |

| Vermont | Coram nobis recognized by Vermont state courts |

| Virginia | Coram vobis recognized by Virginia state courts |

| Washington | Washington Rules of Appellate Procedure 16.4(b) |

| West Virginia | Coram nobis recognized by West Virginia state courts |

| Wisconsin | Coram nobis recognized by Wisconsin state courts |

| Wyoming | Wyoming Rules of Criminal Procedure Rule 35 |

Alabama

Alabama state courts strictly follow the common law definition of the writ of coram nobis where the writ may only be issued to correct errors of fact. The writ may not be issued to correct errors of law. The writ has only been applied to juveniles. The Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals provided the following background and guidelines for coram nobis petitions for state courts in Alabama (citations and quotations removed):

Rule 32, Ala. R. Crim. P. is applicable only to a "Defendant convicted of a criminal offense". Under Alabama law, a juvenile is not convicted of a criminal offense so as to be able to take advantage of the provisions of Rule 32. The writ of error coram nobis is an extraordinary remedy known more for its denial than its approval. Even so, Alabama Courts allow the writ of error coram nobis to attack judgments in certain restricted instances. When no rule or statute controls, "he common law of England, so far as it is not inconsistent with the Constitution, laws and institutions of this state, shall, together with such institutions and laws, be the rule of decisions, and shall continue in force, except as from time to time it may be altered or repealed by the Legislature." § 1-3-1, Ala. Code 1975.

The writ of error coram nobis was one of the oldest remedies of the common law. It lay to correct a judgment rendered by the court upon errors of fact not appearing on the record and so important that if the court had known of them at the trial it would not have rendered the judgment. The ordinary writ of error lay to an appellate court to review an error of law apparent on the record. The writ of error coram nobis lay to the court, and preferably to the judge that rendered the contested judgment. Its purpose was to allow the correction of an error not appearing in the record and of a judgment which presumably would not have been entered had the error been known to the court at the trial. Further, a judgment for the plaintiff in error on an ordinary writ of error may reverse and render the judgment complained of, while a judgment for the petitioner on a writ of error coram nobis necessarily recalls and vacates the judgment complained of and restores the case to the docket for new trial. An evidentiary hearing must be held on a coram nobis petition which is meritorious on its face. An evidentiary hearing on a coram nobis petition are required upon meritorious allegations:

- that counsel was denied.

- that the State used perjured testimony.

- that petitioner was not advised of right to appeal or right to transcript.

- of an ineffective assistance of counsel, specifically, failing to present alibi witnesses and failing to subpoena witnesses.

- of the denial of effective assistance of counsel.

A writ of error coram nobis is also the proper procedural mechanism by which a juvenile who has been adjudicated delinquent may collaterally challenge that adjudication.

Arkansas

Arkansas state courts may issue a writ of coram nobis for only four types of claims: insanity at the time of trial, a coerced guilty plea, material evidence withheld by the prosecutor, or a third-party confession to the crime during the time between conviction and appeal. The Supreme Court of Arkansas provides the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in Arkansas (citations and quotations removed):

An Arkansas trial court can entertain a petition for writ of error coram nobis after a judgment has been affirmed on appeal only after the Arkansas Supreme Court grants permission to recall the case's mandate. A writ of error coram nobis is an extraordinarily rare remedy. Coram nobis proceedings are administered with a strong presumption that the judgment of conviction is valid. The function of the writ is to secure relief from a judgment rendered while there existed some fact that would have prevented its rendition if it had been known to the trial court and which, through no negligence or fault of the defendant, was not brought forward before rendition of the judgment. The petitioner has the burden of demonstrating a fundamental error of fact extrinsic to the record. The court is not required to accept at face value the allegations of the petition.

Due diligence is required in making application for relief, and, in the absence of a valid excuse for delay, the petition will be denied. The mere naked allegation that a constitutional right has been invaded will not suffice. The application should make a full disclosure of specific facts relied upon and not merely state conclusions as to the nature of such facts.

The essence of the writ of coram nobis is that it is addressed to the very court that renders the judgment where injustice is alleged to have been done, rather than to an appellate or other court. The writ is allowed only under compelling circumstances to achieve justice and to address errors of the most fundamental nature. A writ of coram nobis is available to address certain errors of the most fundamental nature that are found in one of four categories:

- Insanity at the time of trial,

- A coerced guilty plea,

- Material evidence withheld by the prosecutor, or

- A third-party confession to the crime during the time between conviction and appeal.

To warrant coram nobis relief, the petitioner has the burden of demonstrating a fundamental error extrinsic to the record that would have prevented rendition of the judgment had it been known and, through no fault of the petitioner, was not brought forward before rendition of judgment. Moreover, the fact that a petitioner merely alleges a Brady violation is not sufficient to provide a basis for coram nobis relief. To establish a Brady violation, three elements are required: (1) the evidence at issue must be favorable to the accused, either because it is exculpatory or because it is impeaching; (2) that evidence must have been suppressed by the State, either willfully or inadvertently; (3) prejudice must have ensued.

California

California state courts strictly follow the common-law definition of the writ of coram nobis where the writ may only be issued to correct errors of fact. The writ may not be issued to correct errors of law. The Supreme Court of California provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in California (citations and quotations removed):

The writ of coram nobis is a non-statutory, common law remedy whose origins trace back to an era in England in which appeals and new trial motions were unknown. Far from being of constitutional origin, the proceeding designated "coram nobis" was contrived by the courts at an early epoch in the growth of common law procedure to provide a corrective remedy because of the absence at that time of the right to move for a new trial and the right of appeal from the judgment. The grounds on which a litigant may obtain relief via a writ of coram nobis are narrower than on habeas corpus. The writ's purpose is to secure relief, where no other remedy exists, from a judgment rendered while there existed some fact which would have prevented its rendition if the trial court had known it and which, through no negligence or fault of the defendant, was not then known to the court.

The principal office of the writ of coram nobis was to enable the same court which had rendered the judgment to reconsider it in a case in which the record still remained before that court. The most comprehensive statement of the office and function of this writ which has come to our notice is the following: The office of the writ of coram nobis is to bring the attention of the court to, and obtain relief from, errors of fact, such as the death of either party pending the suit and before judgment therein; or infancy, where the party was not properly represented by guardian, or coverture, where the common-law disability still exists, or insanity, it seems, at the time of the trial; or a valid defense existing in the facts of the case, but which, without negligence on the part of the defendant, was not made, either through duress or fraud or excusable mistake; these facts not appearing on the face of the record, and being such as, if known in season, would have prevented the rendition and entry of the judgment questioned.

The writ of coram nobis does not lie to correct any error in the judgment of the court nor to contradict or put in issue any fact directly passed upon and affirmed by the judgment itself. If this could be, there would be no end of litigation. The writ of coram nobis is not intended to authorize any court to review and revise its opinions; but only to enable it to recall some adjudication made while some fact existed which, if before the court, would have prevented the rendition of the judgment; and which without fault or negligence of the party, was not presented to the court. It is not a writ whereby convicts may attack or relitigate just any judgment on a criminal charge merely because the unfortunate person may become displeased with his confinement or with any other result of the judgment under attack.

With the advent of statutory new trial motions, the availability of direct appeal, and the expansion of the scope of the writ of habeas corpus, writs of coram nobis had, by the 1930s, become a remedy practically obsolete except in the most rare of instances and applicable to only a very limited class of cases. The statutory motion for new trial has, for most purposes, superseded the common law remedy; and, until recent years, coram nobis was virtually obsolete in California.

The seminal case setting forth the modern requirements for obtaining a writ of coram nobis is People v. Shipman which stated the writ of coram nobis may be granted only when three requirements are met:

- The petitioner must show that some fact exists which, without any fault or negligence on his part, was not presented to the court at the trial on the merits, and which if presented would have prevented the rendition of the judgment.

- The petitioner must show that the newly discovered evidence does not go to the merits of issues tried; issues of fact, once adjudicated, even though incorrectly, cannot be reopened except on motion for new trial. This second requirement applies even though the evidence in question is not discovered until after the time for moving for a new trial has elapsed or the motion has been denied.

- The petitioner must show that the facts upon which he relies were not known to him and could not in the exercise of due diligence have been discovered by him at any time substantially earlier than the time of his motion for the writ.

Several aspects of the test set forth in Shipman illustrate the narrowness of the remedy. Because the writ of coram nobis applies where a fact unknown to the parties and the court existed at the time of judgment that, if known, would have prevented rendition of the judgment, the remedy does not lie to enable the court to correct errors of law. Moreover, the allegedly new fact must have been unknown and must have been in existence at the time of the judgment.

For a newly discovered fact to qualify as the basis for the writ of coram nobis, courts look to the fact itself and not its legal effect. It has often been held that the motion or writ is not available where a defendant voluntarily and with knowledge of the facts pleaded guilty or admitted alleged prior convictions because of ignorance or mistake as to the legal effect of those facts.

Finally, the writ of coram nobis is unavailable when a litigant has some other remedy at law. A writ of coram nobis is not available where the defendant had a remedy by (a) appeal or (b) motion for a new trial and failed to avail himself of such remedies. The writ of coram nobis is not a catch-all by which those convicted may litigate and relitigate the propriety of their convictions ad infinitum. In the vast majority of cases a trial followed by a motion for a new trial and an appeal affords adequate protection to those accused of crime. The writ of coram nobis serves a limited and useful purpose. It will be used to correct errors of fact which could not be corrected in any other manner. But it is well-settled law in this and in other states that where other and adequate remedies exist the writ is not available.

The writ was issued by state courts in California in these types of situations:

- Where the defendant was insane at the time of trial and this fact was unknown to court and counsel.

- Where defendant was an infant and appeared by attorney without the appointment of a guardian or guardian ad litem.

- Where the defendant was a feme covert and her husband was not joined.

- Where the defendant was a slave and was tried and sentenced as a free man.

- Where the defendant was dead at the time judgment was rendered.

- Where default was entered against a defendant who had not been served with summons and who had no notice of the proceeding.

- Where counsel inadvertently entered an unauthorized appearance in behalf of a defendant who had not been served with process.

- Where a plea of guilty was procured by extrinsic fraud.

- Where a plea of guilty was extorted through fear of mob violence.

- Where defendants and their counsel were induced by false representations to remain away from the trial under circumstances amounting to extrinsic fraud.

By contrast, the writ of coram nobis was found unavailable by state courts in California in the following situations:

- Where trial counsel improperly induced the defendant to plead guilty to render him eligible for diversion and the trial court eventually denied diversion.

- Where the defendant pleaded guilty to having a prior felony conviction when he was eligible to have the prior reduced to a misdemeanor.

- Where the defendant discovered new facts that would have bolstered the defense already presented at trial. The court concluded that although the new facts would have been material and possibly beneficial to the defendant at trial, they would not have precluded entry of the judgment.

- Where the defendant mistakenly believed his plea to second degree murder meant he would serve no more than 15 years in prison.

- Where the defendant claimed neither his attorney nor the court had advised him before he pleaded that his convictions would render him eligible for civil commitment under the Sexually Violent Predators Act (SVPA).

- Where the defendant challenged the legality of his arrest, the identity of the informant, and the failure of the court to make findings on the prior convictions. Coram nobis denied on the ground that "all of these matters could have been raised on appeal".

Connecticut

Connecticut state courts strictly follow the common-law definition of the writ of coram nobis where the writ may only be issued to correct errors of fact. The writ may not be issued to correct errors of law. The Supreme Court of Connecticut provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in Connecticut (citations and quotations removed):

A writ of coram nobis is an ancient common-law remedy which is authorized only by the trial judge. The same judge who presided over the trial of the defendant is the only judge with the authority to entertain a writ of coram nobis unless the judge who presided over the case was not available, such as retirement or reassignment. If the original presiding judge is not available, then a judge of the same court must entertain the writ.

The writ must be filed within three years of conviction. This limitation is jurisdictional, so trial courts must dismiss petitions filed after the three-year limitations for lack of jurisdiction. This limitations period for coram nobis petitions has been the law in Connecticut since the 1870s.

The facts must be unknown at the time of the trial without fault of the party seeking relief. The writ must present facts, not appearing in the record, which, if true, would show that such judgment was void or voidable.

A writ of coram nobis lies only in the unusual situation in which no adequate remedy is provided by law. Moreover, when habeas corpus affords a proper and complete remedy the writ of coram nobis will not lie. Prisoners who are in custody may only attack their conviction or sentence through habeas corpus and they are not eligible to file writs of coram nobis.

District of Columbia

District of Columbia courts were established in 1970. The court's authority is derived from the United States Congress rather than from the inherent sovereignty of the states. District of Columbia courts may issue the writ of coram nobis to correct either errors of fact or errors of law. The District of Columbia Court of Appeals provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for District of Columbia courts (citations and quotations removed):

The writ of coram nobis in the District of Columbia is similar to the US Federal Court's interpretation of the writ where the writ of coram nobis is an extraordinary remedy that can be used to correct a legal or factual error.

The primary function of the writ of coram nobis at common law was to correct errors of fact on the part of the trial court, not attributable to the negligence of the defendant, when the errors alleged were of the most fundamental character; that is, such as rendered the proceeding itself irregular and invalid. The writ of provides a petitioner the opportunity to correct errors of fact not apparent on the face of the record and unknown to the trial court. In reviewing a petition for such a writ, there is a presumption that the proceeding in question was without error, and the petitioner bears the burden of showing otherwise.

The writ of coram nobis is available under the All Writs Act, 28 U.S.C. 1651(a) (2006), and the petitioner must show:

- The trial court was unaware of the facts giving rise to the petition;

- The omitted information is such that it would have prevented the sentence or judgment;

- The petitioner is able to justify the failure to provide the information;

- The error is extrinsic to the record; and

- The error is of the most fundamental character.

Maryland

Maryland state courts may issue the writ of coram nobis to correct either errors of fact or errors of law. The Maryland Court of Appeals provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in Maryland (citations and quotations removed):

A convicted petitioner is entitled to relief through the common law writ of coram nobis if and only if:

- The petitioner challenges a conviction based on constitutional, jurisdictional, or fundamental grounds, whether factual or legal;

- The petitioner rebuts the presumption of regularity that attaches to the criminal case;

- The petitioner faces significant collateral consequences from the conviction;

- The issue as to the alleged error has not been waived or "finally litigated in a prior proceeding, intervening changes in the applicable law";

- The petitioner is not entitled to another statutory or common law remedy (for example, the petitioner cannot be incarcerated in a State prison or on parole or probation, as the petitioner likely could then petition for post-conviction relief).

In 2015, the Maryland Code (2014 Supp.), § 8-401 of the Criminal Procedure Article ("CP § 8-401") clarified that the failure to seek an appeal in a criminal case may not be construed as a waiver of the right to file a petition for writ of coram nobis.

A writ denied in a lower state court may be appealed. A writ of coram nobis remains a civil action in Maryland, independent of the underlying action from which it arose. As a coram nobis case is an independent civil action, an appeal from a final judgment in such an action is authorized by the broad language of the general appeals statute, Code § 12-301 of the Courts and Judicial Proceedings Article. An appeal under the general appeals statutes would lie from a final trial court judgment in a coram nobis proceeding. Although the Post Conviction Procedure Act precludes appeals in coram nobis cases brought by an incarcerated person "challenging the validity of incarceration under sentence of imprisonment", neither the Post Conviction Procedure Act nor any other statute which has been called to our attention restricts the right of appeal for a convicted person who is not incarcerated and not on parole or probation, who is suddenly faced with a significant collateral consequence of his or her conviction, and who can legitimately challenge the conviction on constitutional or fundamental grounds. Such person should be able to file a motion for coram nobis relief regardless of whether the alleged infirmity in the conviction is considered an error of fact or an error of law.

Nebraska

Nebraska state courts strictly follow the common-law definition of the writ of coram nobis where the writ may only be issued to correct errors of fact. The writ may not be issued to correct errors of law. The Supreme Court of Nebraska provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in Nebraska (citations and quotations removed):

The common-law writ of coram nobis exists in Nebraska under Nebraska Revised Statutes § 49-101 (Reissue 2010), which adopts English common law to the extent that it is not inconsistent with the Constitution of the United States, the organic law of this state, or any law passed by the Nebraska Legislature.

The purpose of the writ of error coram nobis is to bring before the court rendering judgment matters of fact which, if known at the time the judgment was rendered, would have prevented its rendition. The writ reaches only matters of fact unknown to the applicant at the time of judgment, not discoverable through reasonable diligence, and which are of a nature that, if known by the court, would have prevented entry of judgment. The writ is not available to correct errors of law.

The burden of proof in a proceeding to obtain a writ of coram nobis is upon the applicant claiming the error, and the alleged error of fact must be such as would have prevented a conviction. It is not enough to show that it might have caused a different result.

A writ of coram nobis reaches only matters of fact unknown to the applicant at the time of judgment, not discoverable through reasonable diligence, and which are of a nature that, if known by the court, would have prevented entry of judgment. Claims of errors or misconduct at trial and ineffective assistance of counsel are inappropriate for coram nobis relief. The writ of coram nobis is not available to correct errors of law.

Nevada

Nevada state courts strictly follow the common-law definition of the writ of coram nobis where the writ may only be issued to correct errors of fact. The writ may not be issued to correct errors of law. The Supreme Court of Nevada provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in Nevada (citations and quotations removed):

Nevada Revised Statute 1.030, recognizes the applicability of the common law, and the all-writs language in Article 6, Section 6 of the Nevada Constitution. This statute provides that the common law of England, so far as it is not repugnant to or in conflict with the Constitution and laws of the United States, or the Constitution and laws of Nevada, shall be the rule of decision in all the courts of Nevada. The post-conviction remedy authorized by Nevada statute, NRS 34.724(2)(b), provides that the petitioner must be in actual custody or have suffered a criminal conviction and not completed the sentence imposed pursuant to the judgment of conviction. Therefore, this statute is not available for those who are no longer in custody. Therefore, the common-law writ of coram nobis is available for a person who is not in custody on the conviction being challenged.

The writ of coram nobis may be used to address errors of fact outside the record that affect the validity and regularity of the decision itself and would have precluded the judgment from being rendered. The writ is limited to errors involving facts that were not known to the court, were not withheld by the defendant, and would have prevented entry of the judgment. A factual error does not include claims of newly discovered evidence because these types of claims would not have precluded the judgment from being entered in the first place. A claim of ineffective assistance of counsel also involves legal error and is therefore not available.

Any error that was reasonably available to be raised while the petitioner was in custody is waived, and it is the petitioner's burden on the face of his petition to demonstrate that he could not have reasonably raised his claims during the time he was in custody.

In filing the petition in the trial court is a step in the criminal process; however, the writ of coram nobis should be treated as a civil writ for appeal purposes. The writ is a discretionary writ and so a lower court's ruling on a petition for the writ is reviewed under the abuse of discretion standard in the appellate court.

New Hampshire

New Hampshire courts may issue a writ of coram nobis to correct errors of fact. It is currently undetermined whether the writ may be issued to correct errors of law. The New Hampshire Supreme Court provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in New Hampshire (citations and quotations removed):

The writ of coram nobis is an ancient writ that developed in sixteenth century England. The writ addresses errors discovered when the petitioner is no longer in custody and therefore cannot avail himself of the writ of habeas corpus. Granting such an extraordinary writ is reserved for the rarest of cases.

Because the writ of coram nobis existed within the body of English common law prior to adoption of our constitution, it continues to exist as a matter of New Hampshire common law so long as it is not "repugnant to the rights and liberties contained in constitution". N.H. CONST. pt. II, art. 90. The common law writ of coram nobis is available in New Hampshire courts, because it was in force at the time of the New Hampshire constitution and there is no conflict between the writ of coram nobis and the constitution. The standard of appellate review of the denial of coram nobis is the same as the standard of review for a habeas corpus petition.

Coram nobis is available to correct a constitutional violation. A requirement to bringing a petition for a writ of coram nobis is that sound reasons exist for failing to seek appropriate earlier relief.

New Hampshire courts rely upon habeas corpus procedures to guide its approach to coram nobis proceedings, given the similarities between these avenues for relief. Similarly to habeas petitions, a trial court may deny a petition for a writ of coram nobis without holding an evidentiary hearing if the record clearly demonstrates that the defendant is not entitled to coram nobis relief.

New York

New York state courts may issue a writ of coram nobis only for claims of ineffective assistance of appellate counsel. The Court of Appeals of the State of New York provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in New York (citations and quotations removed):

In New York courts, the writ of coram nobis is available but its application is considerably different than the writ's application in other courts. In 1971, most of the common-law, coram nobis types of relief were abrogated when the New York Criminal Procedure Law § 440.10 (CPL 440.10) was enacted to embrace the deprivation of constitutional rights outside the record; however, the specific category of "ineffective assistance of appellate counsel" was not specified by the Legislature at the time of its enactment.

The U.S. Constitution provides that a criminal defendant must be provided a right to appeal an unconstitutionally deficient performance of counsel. Consistent with the demands of due process, a criminal defendant must be allowed to assert that a right to appeal was extinguished due solely to the unconstitutionally deficient performance of counsel in failing to file a timely notice of appeal.

CPL 460.30 contains a significant restriction as it imposes a one-year limit for the filing of a motion for leave to file a late notice of appeal. Consistent with the due process mandate, CPL 460.30 should not categorically bar an appellate court from considering that a defendant's application to pursue an untimely appeal whenever:

- An attorney has failed to comply with a timely request for the filing of a notice of appeal and

- The defendant alleges that the omission could not reasonably have been discovered within the one-year period, the time limit imposed in CPL 460.30.

Whenever these two criteria are met, the proper procedure is a coram nobis application to the Appellate Division. After CPL 440.10 was enacted, common-law coram nobis proceeding brought in the proper appellate court became the only available and appropriate procedure and forum to review a claim of ineffective assistance of appellate counsel.–

Oregon

In November 2018, the Oregon Court of Appeals determined that the writ of coram nobis is available in rare cases where newly discovered evidence provides clear and convincing evidence of actual innocence. The Oregon Court of Appeals provided the following background and guidelines of coram nobis petitions for state courts in Oregon (citations and quotations removed):

The process that now governs Oregon post-conviction relief claims, the Post-Conviction Hearing Act (PCHA), was enacted in 1959. Before its enactment, Oregon had a complex and confusing array of post-conviction remedies, including writs of habeas corpus (as provided both in the Oregon Constitution and in statutes), writs of coram nobis, motions to correct the record, and motions to vacate the judgment. The PCHA was intended to provide a detailed, unitary procedure to persons seeking postconviction relief.