| Republic of SurinameRepubliek Suriname (Dutch) | |

|---|---|

Flag

Flag

Coat of arms

Coat of arms

| |

| Motto: Justitia – Pietas – Fides (Latin) Gerechtigheid – Vroomheid – Vertrouwen (Dutch) "Justice – Piety – Trust" | |

| Anthem: God zij met ons Suriname (Dutch) "God be with our Suriname" | |

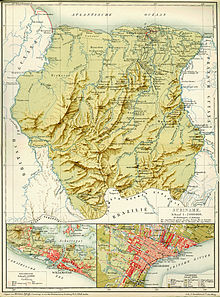

Land controlled by Suriname shown in dark green; claimed land shown in light green. Land controlled by Suriname shown in dark green; claimed land shown in light green. | |

| Capitaland largest city | Paramaribo 5°50′N 55°10′W / 5.833°N 55.167°W / 5.833; -55.167 |

| Official languages | Dutch |

| Recognised regional languages | 8 indigenous languages |

| Other languages | 15 languages |

| Ethnic groups (2012) |

|

| Religion (2012) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Surinamese |

| Government | Unitary assembly-independent republic |

| • President | Chan Santokhi |

| • Vice President | Ronnie Brunswijk |

| • National Assembly Chairman | Marinus Bee |

| • High Court of Justice President | Iwan Rasoelbaks (acting) |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from the Netherlands | |

| • Constituent country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands | 15 December 1954 |

| • Independence from the Kingdom of the Netherlands | 25 November 1975 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 163,820 km (63,250 sq mi) (90th) |

| • Water (%) | 1.1 |

| Population | |

| • 2022 estimate | 632,638 (170th) |

| • Density | 3.9/km (10.1/sq mi) (231st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

| • Total | |

| • Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

| • Total | |

| • Per capita | |

| HDI (2022) | medium (124th) |

| Currency | Surinamese dollar (SRD) |

| Time zone | UTC-3 (SRT) |

| Drives on | Left |

| Calling code | +597 |

| ISO 3166 code | SR |

| Internet TLD | .sr |

Suriname (/ˈsʊərɪnæm, -nɑːm/ SOOR-in-A(H)M, Dutch: [syːriˈnaːmə] , Sranan Tongo: [sraˈnãŋ]), officially the Republic of Suriname (Dutch: Republiek Suriname [reːpyˈblik syːriˈnaːmə]), is a country in northern South America, sometimes considered part of the Caribbean and the West Indies. It is a developing country with a medium level of human development; its economy is heavily dependent on its abundant natural resources, namely bauxite, gold, petroleum, and agricultural products. Suriname is a member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the United Nations, and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

Situated slightly north of the equator, over 90% of its territory is covered by rainforests, the highest proportion of forest cover in the world. Suriname is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north, French Guiana to the east, Guyana to the west, and Brazil to the south. It is the smallest country in South America by both population and territory, with around 612,985 inhabitants in an area of approximately 163,820 square kilometers (63,251 square miles). The capital and largest city is Paramaribo, which is home to roughly half the population.

Suriname was inhabited as early as the fourth millennium BC by various indigenous peoples, including the Arawaks, Caribs, and Wayana. Europeans arrived and contested the area in the 16th century, with the Dutch controlling much of the country's current territory by the late 17th century. Under Dutch rule, Suriname was a lucrative plantation colony focused mostly on sugar; its economy was driven by African slave labour until the abolition of slavery in 1863, after which indentured servants were recruited mostly from British India and the Dutch East Indies. In 1954, Suriname became a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. On 25 November 1975, it became independent following negotiations with the Dutch government. Suriname continues to maintain close diplomatic, economic, and cultural ties with the Netherlands.

Suriname's culture and society strongly reflect the legacy of Dutch colonial rule. It is the only sovereign nation outside Europe where Dutch is the official and prevailing language of government, business, media, and education; an estimated 60% of the population speaks Dutch as a native language. Sranan Tongo, an English-based creole language, is a widely used lingua franca. Most Surinamese are descendants of slaves and indentured labourers brought from Africa and Asia by the Dutch. Suriname is highly diverse, with no ethnic group forming a majority; proportionally, its Muslim and Hindu populations are some of the largest in the Americas. Most people live along the northern coast, centered around Paramaribo, making Suriname one of the least densely populated countries on Earth.

Etymology

The name Suriname may derive from an indigenous people called Surinen, who inhabited the area at the time of European contact. The suffix -ame, common in Surinamese river and place names (see also the Coppename River), may come from aima or eima, meaning river or creek mouth, in Lokono, an Arawak language spoken in the country.

The earliest European sources give variants of "Suriname" as the name of the river on which colonies were eventually founded. Lawrence Kemys wrote in his Relation of the Second Voyage to Guiana of passing a river called "Shurinama" as he travelled along the coast. In 1598, a fleet of three Dutch ships visiting the Wild Coast mention passing the river "Surinamo". In 1617, a Dutch notary spelled the name of the river on which a Dutch trading post had existed three years earlier as "Surrenant".

British settlers, who in 1630 founded the first European colony at Marshall's Creek along the Suriname River, spelled the name "Surinam"; this would long remain the standard spelling in English. The Dutch navigator David Pietersz. de Vries wrote of travelling up the "Sername" river in 1634 until he encountered the English colony there; the terminal vowel remained in future Dutch spellings and pronunciations. The river was called Soronama in a 1640 Spanish manuscript entitled "General Description of All His Majesty's Dominions in America". In 1653, instructions given to a British fleet sailing to meet Lord Willoughby in Barbados, which at the time was the seat of English colonial government in the region, again spelled the name of the colony Surinam. A 1663 royal charter said the region around the river was "called Serrinam also Surrinam".

As a result of the Surrinam spelling, 19th-century British sources offered the folk etymology Surryham, saying it was the name given to the Suriname River by Lord Willoughby in the 1660s in honour of the Duke of Norfolk and Earl of Surrey when an English colony was established under a grant from King Charles II. This folk etymology can be found repeated in later English-language sources.

When the territory was taken over by the Dutch, it became part of a group of colonies known as Dutch Guiana. The official spelling of the country's English name was changed from "Surinam" to "Suriname" in January 1978, but "Surinam" can still be found in English, such as Surinam Airways and the Surinam toad. The older English name is reflected in the English pronunciation, /ˈsjʊərɪnæm, -nɑːm/. In Dutch, the official language of Suriname, the pronunciation is [ˌsyːriˈnaːmə], with a schwa terminal vowel and the main stress on the third syllable.

History

Main article: History of Suriname

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Indigenous settlement of Suriname dates back to 3,000 BC. The largest tribes were the Arawak, a nomadic coastal tribe that lived from hunting and fishing. They were the first inhabitants in the area. The Carib also settled in the area and conquered the Arawak by using their superior sailing ships. They settled in Galibi (Kupali Yumï, meaning "tree of the forefathers") at the mouth of the Marowijne River. While the larger Arawak and Carib tribes lived along the coast and savanna, smaller groups of indigenous people lived in the inland rainforest, such as the Akurio, Trió, Warao, and Wayana.

Colonial period

Main articles: Surinam (English colony) and Surinam (Dutch colony)

Beginning in the 16th century, French, Spanish and English explorers visited the area. A century later, Dutch and English settlers established plantation colonies along the many rivers in the fertile Guiana plains. The earliest documented colony in Guiana was an English settlement named Marshall's Creek along the Suriname River. After that, there was another short-lived English colony called Surinam that lasted from 1650 to 1667.

Disputes arose between the Dutch and the English for control of this territory. In 1667, during negotiations leading to the Treaty of Breda after the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch decided to keep the nascent plantation colony of Surinam they had gained from the English. In return the English kept New Amsterdam, the main city of the former colony of New Netherland in North America on the mid-Atlantic coast. The British renamed it New York, after the Duke of York who would later become King James II of England.

In 1683, the Society of Suriname was founded by the city of Amsterdam, the Van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck family, and the Dutch West India Company. The society was chartered to manage and defend the colony. The planters of the colony relied heavily on African slaves to cultivate, harvest and process the commodity crops of coffee, cocoa, sugar cane and cotton plantations along the rivers. Planters' treatment of the slaves was notoriously brutal even by the standards of the time—historian C. R. Boxer wrote that "man's inhumanity to man just about reached its limits in Surinam"—and many slaves escaped the plantations. In November 1795, the Society was nationalized by the Batavian Republic and from then on the Batavian Republic and its legal successors (the Kingdom of Holland and the Kingdom of the Netherlands) governed the territory as a national colony – barring two periods of British occupation, between 1799 and 1802, and between 1804 and 1816.

With the help of the native South Americans living in the adjoining rain forests, runaway slaves established a new and unique culture in the interior that was highly successful in its own right. They were known collectively in English as Maroons, in French as Nèg'Marrons (literally meaning "brown negroes", that is "pale-skinned negroes"), and in Dutch as Marrons. The Maroons gradually developed several independent tribes through a process of ethnogenesis, as they were made up of slaves from different African ethnicities. These tribes include the Saramaka, Paramaka, Ndyuka or Aukan, Kwinti, Aluku or Boni, and Matawai.

The Maroons often raided plantations to recruit new members from the slaves and capture women, as well as to acquire weapons, food, and supplies. They sometimes killed planters and their families in the raids. Colonists built defenses, which were significant enough that they were shown on 18th-century maps.

The colonists also mounted armed campaigns against the Maroons, who generally escaped through the rainforest, which they knew much better than the colonists did. To end hostilities, in the 18th century, the European colonial authorities signed several peace treaties with different tribes. They granted the Maroons sovereign status and trade rights in their inland territories, giving them autonomy.

Abolition of slavery

Further information: Human rights in SurinameFrom 1861 to 1863, with the American Civil War underway, and enslaved people escaping to Northern territory controlled by the Union, United States President Abraham Lincoln and his administration looked abroad for places to relocate people who were freed from enslavement and who wanted to leave the United States. It opened negotiations with the Dutch government regarding African American emigration to and colonization of the Dutch colony of Suriname. Nothing came of the idea, which was dropped after 1864.

The Netherlands abolished slavery in Suriname in 1863, under a gradual process that required slaves to work on plantations for 10 transition years for minimal pay, which was considered as partial compensation for their masters. After that transition period expired in 1873, most freedmen largely abandoned the plantations where they had worked for several generations in favor of the capital city, Paramaribo. Some of them were able to purchase the plantations they worked on, especially in the district of Para and Coronie. Their descendants still live on those grounds today. Several plantation owners did not pay their former enslaved workers the pay they owed them for the ten years following 1863. They paid the workers with the property rights of the ground of the plantation in order to escape their debt to the workers.

As a plantation colony, Suriname had an economy dependent on labor-intensive commodity crops. To make up for a shortage of labor, the Dutch recruited and transported contract or indentured laborers from the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia) and India (the latter through an arrangement with the British, who then ruled the area). In addition, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, small numbers of laborers, mostly men, were recruited from China and the Middle East.

Although Suriname's population remains relatively small, because of this complex colonization and exploitation, it is one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse countries in the world.

Decolonization

See also: Decolonization of the Americas and Suriname in World War IIDuring World War II, on 23 November 1941, under an agreement with the Netherlands government-in-exile, the United States sent 2,000 soldiers to Suriname to protect the bauxite mines to support the Allies' war effort. In 1942, the Dutch government-in-exile began to review the relations between the Netherlands and its colonies in terms of the post-war period.

In 1954, Suriname became one of the constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, along with the Netherlands Antilles and the Netherlands. In this construction, the Netherlands retained control of its defense and foreign affairs. In 1974, the local government, led by the National Party of Suriname (NPS) (whose membership was largely Creole, meaning ethnically African or mixed African-European), started negotiations with the Dutch government leading towards full independence; in contrast to Indonesia's earlier war for independence from the Netherlands, the path toward Suriname's independence had been an initiative of the then left-wing Dutch government. Independence was granted on 25 November 1975. A large part of Suriname's economy for the first decade following independence was fueled by foreign aid provided by the Dutch government.

Independence

The first President of the country was Johan Ferrier, the former governor, with Henck Arron (the then leader of the NPS) as Prime Minister. In the years leading up to independence, nearly one-third of the population of Suriname emigrated to the Netherlands, amidst concern that the new country would fare worse under independence than it had as a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Surinamese politics did degenerate into ethnic polarisation and corruption soon after independence, with the NPS using Dutch aid money for partisan purposes. Its leaders were accused of fraud in the 1977 elections, in which Arron won a further term, and the discontent was such that a large portion of the population fled to the Netherlands, joining the already significant Surinamese community there.

1980 military coup

Main article: 1980 Surinamese coup d'étatOn 25 February 1980, a military coup overthrew Arron's government. It was initiated by a group of 16 sergeants, led by Dési Bouterse. Opponents of the military regime attempted counter-coups in April 1980, August 1980, 15 March 1981, and again on 12 March 1982. The first counter attempt was led by Fred Ormskerk, the second by Marxist-Leninists, the third by Wilfred Hawker, and the fourth by Surendre Rambocus.

Hawker escaped from prison during the fourth counter-coup attempt, but he was captured and summarily executed. Between 2 am and 5 am on 7 December 1982, the military, under Bouterse's leadership, rounded up 13 prominent citizens who had criticized the military dictatorship and held them at Fort Zeelandia in Paramaribo. The dictatorship had all these men executed over the next three days, along with Rambocus and Jiwansingh Sheombar (who was also involved in the fourth counter-coup attempt).

Civil war, elections, and constitution

The brutal civil war between the Suriname army and Maroons loyal to rebel leader Ronnie Brunswijk, begun in 1986, continued and its effects further weakened Bouterse's position during the 1990s. Due to the civil war, more than 10,000 Surinamese, mostly Maroons, fled to French Guiana in the late 1980s.

National elections were held in 1987. The National Assembly adopted a new constitution that allowed Bouterse to remain in charge of the army. Dissatisfied with the government, Bouterse summarily dismissed the ministers in 1990, by telephone. This event became popularly known as the "Telephone Coup". His power began to wane after the 1991 elections.

At the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, Suriname became the smallest independent South American state to win its first ever Olympic medal as Anthony Nesty won gold in the 100-metre butterfly.

The first half of 1999 was marked by non-violent national protests against poor general economic and social conditions. By mid-year, the Netherlands tried Bouterse in absentia on drug-smuggling charges. He was convicted and sentenced to prison but remained in Suriname.

21st century

On 19 July 2010, Bouterse returned to power when he was elected as the president of Suriname. Before his election in 2010, he, along with 24 others, had been charged with the murders of 15 prominent dissidents in the December murders. However, in 2012, two months before the verdict in the trial, the National Assembly extended its amnesty law and provided Bouterse and the others with amnesty of these charges. He was reelected on 14 July 2015. However, Bouterse was convicted by a Surinamese court on 29 November 2019 and given a 20-year sentence for his role in the 1982 killings.

After winning the 2020 elections, Chan Santokhi was the sole nomination for president of Suriname. On 13 July, Santokhi was elected president by acclamation in an uncontested election. He was inaugurated on 16 July in a ceremony without public attendance due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In February 2023, there were heavy protests against rising living costs in the capital Paramaribo. Protesters accused the government of President Chan Santokhi of corruption. They stormed the National Assembly, demanding the government to resign. However, the government condemned the protests.

Politics

Main article: Politics of Suriname

The Republic of Suriname is a representative democratic republic, based on the Constitution of 1987. The legislative branch of government consists of a 51-member unicameral National Assembly, simultaneously and popularly elected for a five-year term.

In the elections held on Tuesday 25 May 2010, the Megacombinatie won 23 of the National Assembly seats, followed by Nationale Front with 20 seats. A much smaller number, important for coalition-building, went to the "A-combinatie" and to the Volksalliantie. The parties held negotiations to form coalitions. Elections were held on 25 May 2015, and the National Assembly again elected Dési Bouterse as president.

The president of Suriname is elected for a five-year term by a two-thirds majority of the National Assembly. If at least two-thirds of the National Assembly cannot agree to vote for one presidential candidate, a People's Assembly is formed from all National Assembly delegates and regional and municipal representatives who were elected by popular vote in the most recent national election. The president may be elected by a majority of the People's Assembly called for the special election.

As head of government, the president appoints a sixteen-minister cabinet. A vice president is normally elected for a five-year term at the same time as the president, by a simple majority in the National Assembly or People's Assembly. There is no constitutional provision for removal or replacement of the president, except in the case of resignation.

The judiciary is headed by the High Court of Justice of Suriname (Supreme Court). This court supervises the magistrate courts. Members are appointed for life by the president in consultation with the National Assembly, the State Advisory Council, and the National Order of Private Attorneys.

Foreign relations

Main article: Foreign relations of Suriname

Due to Suriname's Dutch colonial history, Suriname had a long-standing special relationship with the Netherlands.

In 1999, Dési Bouterse was convicted and sentenced in absentia in the Netherlands to 11 years of imprisonment for drug trafficking. He was the main suspect in the court case concerning the December murders, the 1982 assassination of opponents of military rule in Fort Zeelandia, Paramaribo. He served as president between 2010 and 2020. These two cases still strain relations between the Netherlands and Suriname.

The Dutch government stated during that time that it would maintain limited contact with the president.

Bouterse was elected as president of Suriname in 2010. The Netherlands in July 2014 dropped Suriname as a member of its development program.

Since 1991, the United States has maintained positive relations with Suriname. The two countries work together through the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI) and the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Suriname also receives military funding from the U.S. Department of Defense.

Suriname has been a member of The Forum of Small States (FOSS) since the group's founding in 1992.

European Union relations and cooperation with Suriname are carried out both on a bilateral and a regional basis. There are ongoing EU-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and EU-CARIFORUM dialogues. Suriname is party to the Cotonou Agreement, the partnership agreement among the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States and the European Union.

On 17 February 2005, the leaders of Barbados and Suriname signed the "Agreement for the deepening of bilateral cooperation between the Government of Barbados and the Government of the Republic of Suriname." On 23–24 April 2009, both nations formed a Joint Commission in Paramaribo, Suriname, to improve relations and to expand into various areas of cooperation. They held a second meeting toward this goal on 3–4 March 2011, in Dover, Barbados. Their representatives reviewed issues of agriculture, trade, investment, as well as international transport.

In the late 2000s, Suriname intensified development cooperation with other developing countries. China's South-South cooperation with Suriname has included a number of large-scale infrastructure projects, including port rehabilitation and road construction. Brazil signed agreements to cooperate with Suriname in education, health, agriculture, and energy production.

Military

Main article: Military of SurinameThe Armed Forces of Suriname have three branches: the Army, the Air Force, and the Navy. The president of the Republic is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces (Opperbevelhebber van de Strijdkrachten). The president is assisted by the minister of defence. Beneath the president and minister of defence is the commander of the armed forces (Bevelhebber van de Strijdkrachten). The military branches and regional military commands report to the commander.

After the creation of the Statute of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Royal Netherlands Army was entrusted with the defense of Suriname, while the defense of the Netherlands Antilles was the responsibility of the Royal Netherlands Navy. The army set up a separate Troepenmacht in Suriname (Forces in Suriname, TRIS). Upon independence in 1975, this force was turned into the Surinaamse Krijgsmacht (SKM):, Surinamese Armed Forces. After the 1980 overthrow of the government, the SKM was rebranded as the Nationaal Leger (NL), National Army.

In 1965, the Dutch and Americans used Suriname's Coronie site for multiple Nike Apache sounding rocket launches.

Administrative divisions

Main articles: Districts of Suriname and Resorts of Suriname

The country is divided into ten administrative districts, each headed by a district commissioner appointed by the president, who also has the power of dismissal. Suriname is further subdivided into 62 resorts (ressorten).

| District | Capital | Area (km) | Area (%) | Population (2012 census) |

Population (%) | Pop. dens. (inhabitants/km) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nickerie | Nieuw Nickerie | 5,353 | 3.3 | 34,233 | 6.3 | 6.4 |

| 2 | Coronie | Totness | 3,902 | 2.4 | 3,391 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| 3 | Saramacca | Groningen | 3,636 | 2.2 | 17,480 | 3.2 | 4.8 |

| 4 | Wanica | Lelydorp | 443 | 0.3 | 118,222 | 21.8 | 266.9 |

| 5 | Paramaribo | Paramaribo | 182 | 0.1 | 240,924 | 44.5 | 1323.8 |

| 6 | Commewijne | Nieuw-Amsterdam | 2,353 | 1.4 | 31,420 | 5.8 | 13.4 |

| 7 | Marowijne | Albina | 4,627 | 2.8 | 18,294 | 3.4 | 4.0 |

| 8 | Para | Onverwacht | 5,393 | 3.3 | 24,700 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| 9 | Sipaliwini | none | 130,567 | 79.7 | 37,065 | 6.8 | 0.3 |

| 10 | Brokopondo | Brokopondo | 7,364 | 4.5 | 15,909 | 2.9 | 2.2 |

| SURINAME | Paramaribo | 163,820 | 100.0 | 541,638 | 100.0 | 3.3 |

Geography

Main article: Geography of Suriname

Suriname is the smallest independent country in South America. Situated on the Guiana Shield, it lies mostly between latitudes 1° and 6°N, and longitudes 54° and 58°W. The country can be divided into two main geographic regions. The northern, lowland coastal area (roughly above the line Albina-Paranam-Wageningen) has been cultivated, and most of the population lives here. The southern part consists of tropical rainforest and sparsely inhabited savanna along the border with Brazil, covering about 80% of Suriname's land surface.

The two main mountain ranges are the Bakhuys Mountains and the Van Asch Van Wijck Mountains. Julianatop is the highest mountain in the country at 1,286 metres (4,219 ft) above sea level. Other mountains include Tafelberg at 1,026 metres (3,366 ft), Mount Kasikasima at 718 metres (2,356 ft), Goliathberg at 358 metres (1,175 ft) and Voltzberg at 240 metres (790 ft).

Suriname contains six terrestrial ecoregions: Guayanan Highlands moist forests, Guianan moist forests, Paramaribo swamp forests, Tepuis, Guianan savanna, and Guianan mangroves. Its forest cover is 90.2%, the highest of any nation in the world. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.39/10, ranking it fifth globally out of 172 countries.

Borders

Main article: Borders of Suriname

Suriname is situated between French Guiana to the east and Guyana to the west. The southern border is shared with Brazil and the northern border is the Atlantic coast. The southernmost borders with French Guiana and Guyana are disputed by these countries along the Marowijne and Corantijn rivers, respectively, while a part of the disputed maritime boundary with Guyana was arbitrated by the Permanent Court of Arbitration convened under the rules set out in Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on 20 September 2007.

Climate

Lying two to five degrees north of the equator, Suriname has a very hot and wet tropical climate, and temperatures do not vary much throughout the year. Average relative humidity is between 80% and 90%. Its average temperature ranges from 29 to 34 °C (84 to 93 °F). Due to the high humidity, actual temperatures are distorted and may therefore feel up to 6 °C (11 °F) hotter than the recorded temperature.

The year has two wet seasons, from April to August and from November to February. It also has two dry seasons, from August to November and February to April.

Climate change in Suriname is leading to warmer temperatures and more extreme weather events. As a relatively poor country, its contributions to global climate change have been limited. Because of the large forest cover, the country has been running a carbon negative economy since 2014.

Biodiversity and conservation

Main article: Biodiversity in Suriname

Due to the variety of habitats and temperatures, biodiversity in Suriname is considered high. In October 2013, 16 international scientists researching the ecosystems during a three-week expedition in Suriname's Upper Palumeu River Watershed catalogued 1,378 species and found 60—including six frogs, one snake, and 11 fish—that may be previously unknown species. According to the environmental non-profit Conservation International, which funded the expedition, Suriname's ample supply of fresh water is vital to the biodiversity and healthy ecosystems of the region.

Snakewood (Brosimum guianense), a tree, is native to this tropical region of the Americas. Customs in Suriname report that snakewood is often illegally exported to French Guiana, thought to be for the crafts industry.

On 21 March 2013, Suriname's REDD+ Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP 2013) was approved by the member countries of the Participants Committee of the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF).

As in other parts of Central and South America, indigenous communities have increased their activism to protect their lands and preserve habitat. In March 2015, the "Trio and Wayana communities presented a declaration of cooperation to the National Assembly of Suriname that announces an indigenous conservation corridor spanning 72,000 square kilometers (27,799 square miles) of southern Suriname. The declaration, led by these indigenous communities and with the support of Conservation International (CI) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Guianas, comprises almost half of the total area of Suriname. This area includes large forests and is considered "essential for the country's climate resilience, freshwater security, and green development strategy."

The Central Suriname Nature Reserve has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its unspoiled forests and biodiversity. There are many national parks in the country, including Galibi National Reserve along the coast; Brownsberg Nature Park and Eilerts de Haan Nature Park in central Suriname; and the Sipaliwani Nature Reserve on the Brazilian border. In all, 16% of the country's land area is national parks and lakes, according to the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

Suriname's extensive tree cover is vital to the country's efforts to mitigate climate change and maintain carbon negativity.

Economy

Main article: Economy of Suriname

Suriname's democracy gained some strength after the turbulent 1990s, and its economy became more diversified and less dependent on Dutch financial assistance. Bauxite (aluminium ore) mining used to be a strong revenue source, since before the independence of the country up to 2015. Because Alcoa stopped all bauxite operations, the bauxite era in Suriname also ended.

The discovery, exploration and exploitation of oil and gold nowadays contributes substantially to Suriname's economic independence. Agriculture, especially rice and bananas, remains a strong component of the economy, and ecotourism is providing new economic opportunities. More than 93% of Suriname's landmass consists of unspoiled rainforest. With the establishment of the Central Suriname Nature Reserve in 1998, Suriname signaled its commitment to the conservation of this precious resource. The Central Suriname Nature Reserve became a World Heritage Site in 2000.

The economy of Suriname was dominated by the bauxite industry, which accounted for more than 15% of GDP and 70% of export earnings up to 2015. Currently gold exports make up 60-80% of all exports earnings. In 2021 the gold industry accounted for 8.5% of the GDP. The share of large-scale mining in total gold production is 58% compared to 42% of small-scale mining. With an export value of US$1.83 billion in 2023, the gold sector makes an important contribution to the economy. The gold production of Suriname in 2015 is 30 metric tonnes.

The exploration and exploitation of oil adds substantially to the economy of Suriname at about 10% of the GDP. The national oil company, STAATSOLIE, is the motor behind Suriname's oil industry. Their core business is oil extraction and refining. In 2022 they made a revenue of US$840 million. In that year their contribution to the state treasury was US$320 million. In 2023 they made a revenue of US$722 million. The drop in revenue was because of the lower price for oil per barrel that year. Their contribution to the Surinamese state treasury was US$335 million.

Other main export products include rice, bananas, and shrimp. Suriname has recently started exploiting some of its sizeable oil and gold reserves. About a quarter of the people work in the agricultural sector. The Surinamese economy is very dependent on commerce, its main trade partners being, Switzerland, China, the Netherlands, the United States, Canada, and Caribbean countries, mainly Trinidad and Tobago and the islands of the former Netherlands Antilles.

After assuming power in the fall of 1996, the Wijdenbosch government ended the structural adjustment program of the previous government, claiming it was unfair to the poorer elements of society. Tax revenues fell as old taxes lapsed and the government failed to implement new tax alternatives. By the end of 1997, the allocation of new Dutch development funds was frozen as Surinamese Government relations with the Netherlands deteriorated. Economic growth slowed in 1998, with decline in the mining, construction, and utility sectors. Rampant government expenditures, poor tax collection, a bloated civil service, and reduced foreign aid in 1999 contributed to the fiscal deficit, estimated at 11% of GDP. The government sought to cover this deficit through monetary expansion, which led to a dramatic increase in inflation. It takes longer on average to register a new business in Suriname than virtually any other country in the world (694 days or about 99 weeks).

- GDP (2010 est.): US$4.794 billion.

- Annual growth rate real GDP (2010 est.): 3.5%.

- Per capita GDP (2010 est.): US$9,900.

- Inflation (2007): 6.4%.

- Natural resources: Bauxite, gold, oil, iron ore, other minerals; forests; hydroelectric potential; fish and shrimp.

- Agriculture: Products—rice, bananas, timber, palm kernels, coconuts, peanuts, citrus fruits, and forest products.

- Industry: Types—alumina, oil, gold, fish, shrimp, lumber.

- Trade:

- Exports (2012): US$2.563 billion: alumina, gold, crude oil, lumber, shrimp and fish, rice, bananas. Major consumers: US 26.1%, Belgium 17.6%, UAE 12.1%, Canada 10.4%, Guyana 6.5%, France 5.6%, Barbados 4.7%.

- Imports (2012): US$1.782 billion: capital equipment, petroleum, foodstuffs, cotton, consumer goods. Major suppliers: US 25.8%, Netherlands 15.8%, China 9.8%, UAE 7.9%, Antigua and Barbuda 7.3%, Netherlands Antilles 5.4%, Japan 4.2%.

Demographics

Main articles: Demographics of Suriname and Surinamese people

In 2022, Suriname had a population of roughly 618,040 according to estimates by the United Nations. This compares to 541,638 inhabitants from the 2012 census. The Surinamese populace is characterized by high levels of diversity, wherein no particular demographic group constitutes a majority. This is a legacy of centuries of Dutch rule, which entailed successive periods of forced, contracted, or voluntary migration by various nationalities and ethnic groups from around the world.

Ethnicity

| Ethnic groups of Suriname | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic groups | percent | |||

| Indian | 27.4% | |||

| Maroon | 21.7% | |||

| Creole | 15.7% | |||

| Javanese | 13.7% | |||

| Mixed | 13.4% | |||

| Amerindian | 3.8% | |||

| Chinese | 1.5% | |||

| White | 0.3% | |||

| Other | 2.5% | |||

The largest ethnic group are Asian Surinamese (about 43%), with the largest subgroup being Indo-Surinamese, who form over a quarter of the population (27.4%). The vast majority are descendants of 19th-century indentured workers from India, hailing mostly from Bhojpuri speaking areas of modern Bihar, Jharkhand, and northeastern Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and southeastern Tamil Nadu. If counted as one ethnic group, the Afro-Surinamese are the second largest community, at around 37.4%; however, they are usually divided into two cultural/ethnic groups: the Creoles and the Maroons. Surinamese Maroons, whose ancestors are mostly runaway slaves that fled to the interior, comprise 21.7% of the population. They are divided into six tribes: Ndyuka (Aucans), Saramaccans, Paramaccans, Kwinti, Aluku (Boni) and Matawai. Surinamese Creoles, mixed people descending from African slaves and Europeans (mostly Dutch), form 15.7% of the population. Javanese make up 14% of the population, and like the East Indians, descend largely from workers contracted from the island of Java in the former Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia). 13.4% of the population identifies as being of mixed ethnic heritage. Chinese, originating from 19th-century indentured workers and some recent migration, make up 7.3% of the population.

Other groups include Lebanese, primarily Maronites, and Jews of Sephardic and Ashkenazi origin, whose center of population was Jodensavanne. Various indigenous peoples make up 3.7% of the population, with the main groups being the Akurio, Arawak, Kalina (Caribs), Tiriyó and Wayana. They live mainly in the districts of Paramaribo, Wanica, Para, Marowijne and Sipaliwini. A small but influential number of Europeans remain in the country, comprising about 1% of the population. They are descended mostly from Dutch 19th-century immigrant farmers, known as "Boeroes" (derived from boer, the Dutch word for "farmer"), and to a lesser degree other European groups, such as Portuguese. Many Boeroes left after independence in 1975.

More recently Suriname has seen a new wave of immigrants, namely Brazilians and Chinese (many of them laborers mining for gold). Most do not have legal status.

Emigration

The option to choose between Surinamese or Dutch citizenship in the years leading up to Suriname's independence in 1975 led to a mass migration to the Netherlands. This migration continued in the period immediately after independence and during military rule in the 1980s and for largely economic reasons extended throughout the 1990s. The Surinamese community in the Netherlands numbered 350,300 as of 2013 (including children and grandchildren of Suriname migrants born in the Netherlands), compared to approximately 566,000 Surinamese in Suriname itself.

According to the International Organization for Migration, around 272,600 people from Suriname lived in other countries in the late 2010s, in particular in the Netherlands (c. 192,000), France (c. 25,000, most of them in French Guiana), the United States (c. 15,000), Guyana (c. 5,000), Aruba (c. 1,500), and Canada (c. 1,000).

Religion

Main article: Religion in SurinameReligion in Suriname (2012 census)

Protestantism (25.6%) Catholic (21.6%) Other Christian (1.2%) Hinduism (22.3%) Islam (13.9%) Winti (1.8%) Kejawen (0.8%) Other religion (2.1%) None (7.5%) Not stated (3.2%)

Suriname's religious makeup is heterogeneous and reflective of the country's multicultural character. According to Pew research from 2012, Christians are the largest religious community, at slightly over half the population (51.6%), followed by Hindus (19.8%) and Muslims (15.2%); other religious minorities include adherents of various folk traditions (5.3%), Buddhists (<1%), Jews (<1%), practitioners of other faiths (1.8%), and unaffiliated (5.4%).

According to the 2020 census, 52.3% of Surinamese were Christians; 26.7% were Protestants (11.18% Pentecostal, 11.16% Moravian, 0.7% Reformed (including Remonstrants), and 4.4% other Protestant denominations), while 21.6% were Catholics. Hindus are the second largest religious group in Suriname, comprising nearly one-fifth of the population (18.8% in 2020), the third largest proportion of any country in the Western Hemisphere, after Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago, both of which also have large proportions of Indians. Likewise, almost all practitioners of Hinduism are found among the Indo-Surinamese population. Muslims constitute 14.3% of the population, the highest proportion of Muslims in the Americas. They are largely of Javanese or Indian descent. Folk religions are practiced by 5.6% of the population and include Winti, an Afro-American religion practiced mostly by those of Maroon ancestry, Javanism (0.8%), a syncretic faith found among some Javanese Surinamese, and various indigenous folk traditions that are often incorporated into one of the larger religions (usually Christianity). In the 2020 census, 6.2% of the population declared they had "no religion", while a further 1.9% adhere to "other religions".

Languages

Suriname has roughly 14 local languages, but Dutch (Nederlands) is the sole official language and is the language used in education, government, business, and the media. Over 60% of the population are native speakers of Dutch and around 20%–30% speak it as a second language. In 2004, Suriname became an associate member of the Dutch Language Union.

Suriname is one of three Dutch-speaking sovereign countries in the world (the others being the Netherlands and Belgium). It is also the only area in the Americas where Dutch is spoken by a majority of the population (as territories in the Dutch Caribbean all have other majority languages). Finally, Suriname and English-speaking Guyana are the only countries in South America along with English-speaking British dependent territory of Falkland Islands where a Romance language does not predominate.

In Paramaribo, Dutch is the main home language in two-thirds of the households. The recognition of "Surinaams-Nederlands" ("Surinamese Dutch") as a national dialect equal to "Nederlands-Nederlands" ("Dutch Dutch") and "Vlaams-Nederlands" ("Flemish Dutch") was expressed in 2009 by the publication of the Woordenboek Surinaams Nederlands (Surinamese–Dutch Dictionary). It is the most commonly spoken language in urban areas. The local languages are only more predominant than Dutch in the interior of Suriname (namely parts of Sipaliwini and Brokopondo).

Sranan Tongo, a local English-based creole language, is the most widely used vernacular language in daily life and business among the Surinamese. Together with Dutch, it is considered to be one of the two principal languages of Surinamese diglossia. Both are further influenced by other spoken languages which are spoken primarily within ethnic communities. Sranan Tongo is often used interchangeably with Dutch depending on the formality of the setting; Dutch is seen as a prestige dialect and Sranan Tongo the common vernacular.

Sarnami Hindustani, a fusion of Bhojpuri and Awadhi languages, is the third-most used language. It is primarily spoken by the descendants of Indian indentured labourers from the former British India.

The six Maroon languages of Suriname are also considered English-based creole languages, and include Saramaccan, Aukan, Aluku, Paramaccan, Matawai and Kwinti. Aluku, Paramaccan, and Kwinti are so mutually intelligible with Aukan that they can be considered dialects of the Aukan language. The same can be said about Matawai, which is mutually intelligible with Saramaccan.

Javanese is used by the residents of Suriname who are descendants of the Javanese indentured laborers once sent from the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

Amerindian languages include Akurio, Arawak-Lokono, Carib-Kari'nja, Sikiana-Kashuyana, Tiro-Tiriyó, Waiwai, Warao, and Wayana.

Hakka and Cantonese are spoken by the descendants of the Chinese indentured labourers. Mandarin is spoken by the recent wave of Chinese immigrants.

English, Guyanese English Creole, Portuguese, Spanish, French, and French Guianese Creole are spoken at areas near the country's borders where there are many migrants from neighboring countries speaking their respective languages.

Largest cities

The national capital, Paramaribo, is by far the dominant urban area, accounting for nearly half of Suriname's population and most of its urban residents. Indeed, its population is greater than the next nine largest cities combined. Most municipalities are located within the capital's metropolitan area, or along the densely populated coastline; about 90% of the population lives in Paramaribo or on the coast.

| Largest cities or towns in Suriname | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

Paramaribo  Lelydorp |

1 | Paramaribo | Paramaribo | 223 757 |  Nieuw Nickerie  Moengo | ||||

| 2 | Lelydorp | Wanica | 18 223 | ||||||

| 3 | Nieuw Nickerie | Nickerie | 13 143 | ||||||

| 4 | Moengo | Marowijne | 7 074 | ||||||

| 5 | Nieuw Amsterdam | Commewijne | 4 935 | ||||||

| 6 | Mariënburg | Commewijne | 4 427 | ||||||

| 7 | Wageningen | Nickerie | 4 145 | ||||||

| 8 | Albina | Marowijne | 3 985 | ||||||

| 9 | Groningen | Saramacca | 3 216 | ||||||

| 10 | Brownsweg | Brokopondo | 2 696 | ||||||

Culture

Main article: Culture of Suriname See also: Music of Suriname

Owing to the country's multicultural heritage, Suriname celebrates a variety of distinct ethnic and religious festivals.

National holidays

- 1 January – New Year's Day

- January/February – Chinese New Year

- March (varies) – Phagwah

- March/April – Good Friday

- March/April – Easter

- March/April – Easter Monday

- 1 May – Labour Day

- 1 July – Keti Koti (Emancipation Day – end of slavery)

- 9 August – Indigenous People's Day

- 10 October – Day of the Maroons

- October/November – Diwali

- 25 November – Independence Day

- 25 December – Christmas

- 26 December – Boxing Day

- varies – Eid-ul-adha

- varies – Eid-ul-Fitr

- varies – Satu Suro/Islamic New Year

There are several Hindu and Islamic national holidays like Diwali, Phagwa, and Eid-ul-adha. These holidays do not have fixed dates on the Gregorian calendar, as they are based on the Hindu and Islamic calendars, respectively. As of 2020, Eid-ul-adha is a national holiday, and equal to a Sunday.

There are several holidays which are unique to Suriname. These include the Prawas Din (Indian), Javanese, and Chinese arrival days. They celebrate the arrival of the first ships with their respective immigrants.

New Year's Eve

New Year's Eve in Suriname is called Oud jaar, Owru Yari, or "old year". Firecrackers called pagaras which have long ribbons attached and are detonated at midnight.

Sports

The major sports in Suriname are football, basketball, and volleyball. The Suriname Olympic Committee is the national governing body for sports in Suriname. The major mind sports are chess, draughts, bridge and troefcall.

Many Suriname-born football players and Dutch-born football players of Surinamese descent have turned out to play for the Dutch national team, including Gerald Vanenburg, Ruud Gullit, Frank Rijkaard, Edgar Davids, Clarence Seedorf, Patrick Kluivert, Aron Winter, Georginio Wijnaldum, Virgil van Dijk, and Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink. In 1999, Humphrey Mijnals, who played for both Suriname and the Netherlands, was elected Surinamese footballer of the century. Another famous player is André Kamperveen, who captained Suriname in the 1940s and was the first Surinamese to play professionally in the Netherlands.

In 2021 Suriname participated in their first CONCACAF Gold Cup where they played against Costa Rica, Jamaica and Guadeloupe in Group C. Suriname lost its first two matches against Jamaica and Costa Rica, but ended third in the group following a 2–1 win against Guadeloupe.

Swimmer Anthony Nesty is the only Olympic medalist for Suriname. He won gold in the 100-meter butterfly at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul and he won bronze in the same discipline at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona. Originally from Trinidad and Tobago, he now lives in Gainesville, Florida, and is the head coach of the University of Florida swim team.

The most famous international track & field athlete from Suriname is Letitia Vriesde, who won a silver medal at the 1995 World Championships behind Ana Quirot in the 800 metres, the first medal won by a South American female athlete in World Championship competition. In addition, she also won a bronze medal at the 2001 World Championships and won several medals in the 800 and 1500 metres at the Pan-American Games and Central American and Caribbean Games. Tommy Asinga also received acclaim for winning a bronze medal in the 800 metres at the 1991 Pan American Games.

Cricket is popular in Suriname to some extent, influenced by its popularity in the Netherlands and in neighbouring Guyana. The Surinaamse Cricket Bond is an associate member of the International Cricket Council (ICC). Suriname and Argentina were the only ICC associate members in South America when ICC had a three tiered membership, although Guyana is represented on the West Indies Cricket Board, a full member. The national cricket team was ranked 47th in the world and sixth in the ICC Americas region as of June 2014, and competes in the World Cricket League (WCL) and ICC Americas Championship. Iris Jharap, born in Paramaribo, played women's One Day International matches for the Dutch national side, the only Surinamese to do so.

In the sport of badminton, another popular sport in Suriname especially with the youth, the local heroes are Virgil Soeroredjo, Mitchel Wongsodikromo, Sören Opti and also Crystal Leefmans. All winning medals for Suriname at the Carebaco Caribbean Championships, the Central American and Caribbean Games (CACSO Games) and also at the South American Games, better known as the ODESUR Games. Virgil Soeroredjo also participated for Suriname at the 2012 London Summer Olympics, only the second badminton player, after Oscar Brandon, for Suriname to achieve this. National Champion Sören Opti became the third Surinamese badminton player to participate at the Summer Olympics in 2016.

Multiple time K-1 kickboxing world champions Ernesto Hoost and Remy Bonjasky were born in Suriname or are of Surinamese descent. Other kickboxing world champions include Gilbert Ballantine, Rayen Simson, Melvin Manhoef, Tyrone Spong, Andy Ristie, Jairzinho Rozenstruik, Regian Eersel, and Donovan Wisse.

Suriname also has a national korfball team, with korfball being a Dutch sport. Vinkensport is also practised.

In 2016, the Sports Hall of Fame Suriname was established in the building of the Suriname Olympic Committee and is dedicated to the achievements of the Surinamese sporters.

Transportation

See also: Transport in Suriname, Desiré Delano Bouterse Highway, and East-West Link (Suriname)Road

Suriname, along with neighboring Guyana, is one of only two countries on the mainland South American continent that drive on the left, although many vehicles are left-hand-drive as well as right-hand-drive. One explanation for this practice is that at the time of its colonization of Suriname, the Netherlands itself used left-hand traffic, also introducing the practice in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia. Another is that Suriname was first colonized by the British, and for practical reasons, this was not changed when it came under Dutch administration. Although the Netherlands converted to driving to the right at the end of the 18th century, Suriname did not. As of 2003, Suriname had 4303 km (2674 miles) of roads, of which 1119 km (695 miles) are paved.

Air

The country has 55 mostly small airports, of which only six are paved. The only international airport that supports large jet aircraft is Johan Adolf Pengel International Airport.

Airlines with departures from Suriname:

- American Airlines

- Blue Wing Airlines

- Gum Air

- Fly All Ways

- Surinam Airways (SLM)

Airlines with arrivals in Suriname:

- Caribbean Airlines (Trinidad and Tobago)

- KLM (Netherlands)

- Gol Transportes Aéreos (Brazil)

- Copa Airlines (Panama)

- Tui (Netherlands)

- Fly All Ways (Curaçao), Cuba (Havana), (Santiago de Cuba)

- Surinam Airways (SLM) (Aruba), Brazil (Belém), (Curaçao), Guyana (Georgetown), Netherlands (Amsterdam), Trinidad and Tobago (Port of Spain), and the United States (Miami).

Other national companies with an air operator certification:

- Aero Club Suriname (ACS) – General Aviation Aeroclub

- Coronie Aero Farmers (CAF) – Agriculture Cropdusting

- Eagle Air Services (EAS) – Agriculture Cropdusting

- ERK Farms (ERK) – Agriculture Cropdusting

- Overeem Air Service (OAS) – General Aviation Charters

- Pegasus Air Service (PAS) – Helicopter Charters

- Suriname Air Force / Surinaamse Luchtmacht (SAF / LUMA) – Military Aviation Surinam Air Force

- Surinam Sky Farmers (SSF) – Agriculture Cropdusting

- Surinaamse Medische Zendings Vliegdienst (MAF – Mission Aviation Fellowship) – General Aviation Missionary

- Vortex Aviation Suriname (VAS) – General Aviation Maintenance & Flightschool

Health

Main article: Health in Suriname

The Global Burden of Disease Study provides an on-line data source for analyzing updated estimates of health for 359 diseases and injuries and 84 risk factors from 1990 to 2017 in most of the world's countries. Comparing Suriname with other Caribbean nations show that in 2017 the age-standardized death rate for all causes was 793 (males 969, females 641) per 100,000, far below the 1219 of Haiti, somewhat below the 944 of Guyana but considerably above the 424 of Bermuda. In 1990, the death rate was 960 per 100,000. Life expectancy in 2017 was 72 years (males 69, females 75). The death rate for children < 5 years was 581 per 100,000 compared to 1308 in Haiti and 102 in Bermuda. In 1990 and 2017, the leading causes of age-standardized death rates were cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes/chronic kidney disease.

Education

Main article: Education in Suriname

Education in Suriname is compulsory until the age of 12, and the nation had a net primary enrollment rate of 94% in 2004. Literacy is very common, particularly among men. The main university in the country is the Anton de Kom University of Suriname.

From elementary school to high school there are 13 grades. The elementary school has six grades, middle school four grades, and high school three grades. Students take a test at the end of elementary school to determine whether they will go to the MULO (secondary modern school) or a middle school of lower standards like LBO.

Media

Traditionally, De Ware Tijd was the major newspaper of the country, but since the '90s Times of Suriname, De West and Dagblad Suriname have also been well-read newspapers. All publish primarily in Dutch.

Suriname has twenty-four radio stations, most of them also broadcast through the Internet. There are twelve television sources: ABC (Ch. 4–1, 2), RBN (Ch. 5–1, 2), Rasonic TV (Ch. 7), STVS (Ch. 8–1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6), Apintie (Ch. 10–1), ATV (Ch. 12–1, 2, 3, 4), Radika (Ch. 14), SCCN (Ch. 17–1, 2, 3), Pipel TV (Ch. 18–1, 2), Trishul (Ch. 20–1, 2, 3, 4), Garuda (Ch. 23–1, 2, 3), Sangeetmala (Ch. 26), Ch. 30, Ch. 31, Ch.32, Ch.38, SCTV (Ch. 45). Also listened to is mArt, a broadcaster from Amsterdam founded by people from Suriname. Kondreman is one of the popular cartoons in Suriname.

There are also three major news sites: Starnieuws, Suriname Herald, and GFC Nieuws.

In 2022, Suriname ranked 52nd in the worldwide Press Freedom Index by the organization Reporters Without Borders, a strong drop in the ranking compared to the 2018–2021 period (about location 20).

Tourism

Most tourists visit Suriname for the biodiversity of the Amazonian rain forests in the south of the country, which are noted for their flora and fauna. The Central Suriname Nature Reserve is the biggest and one of the most popular reserves, along with the Brownsberg Nature Park which overlooks the Brokopondo Reservoir, one of the largest human-made lakes in the world. In 2008, the Berg en Dal Eco & Cultural Resort opened in Brokopondo. Tonka Island in the reservoir is home to a rustic eco-tourism project run by the Saramaccaner Maroons. Pangi wraps and bowls made of calabashes are the two main products manufactured for tourists. The Maroons have learned that colorful and ornate pangis are popular with tourists. Other popular decorative souvenirs are hand-carved purple-hardwood made into bowls, plates, canes, wooden boxes, and wall decors.

There are also many waterfalls throughout the country. Raleighvallen, or Raleigh Falls, is a 56,000-hectare (140,000-acre) nature reserve on the Coppename River, rich in bird life. Also are the Blanche Marie Falls on the Nickerie River and the Wonotobo Falls. Tafelberg Mountain in the centre of the country is surrounded by its own reserve – the Tafelberg Nature Reserve – around the source of the Saramacca River, as is the Voltzberg Nature Reserve further north on the Coppename River at Raleighvallen. In the interior are many Maroon and Amerindian villages, many of which have their own reserves that are generally open to visitors.

Suriname is one of the few countries in the world where at least one of each biome that the state possesses has been declared a wildlife reserve. Around 30% of the total land area of Suriname is protected by law as reserves.

Other attractions include plantations such as Laarwijk, which is situated along the Suriname River. This plantation can be reached only by boat via Domburg, in the north central Wanica District of Suriname.

Crime rates continue to rise in Paramaribo and armed robberies are not uncommon. According to the current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of the 2018 report's publication, Suriname has been assessed as Level 1: exercise normal precautions.

Landmarks

The Jules Wijdenbosch Bridge is a bridge over the river Suriname between Paramaribo and Meerzorg in the Commewijne district. The bridge was built during the tenure of President Jules Albert Wijdenbosch (1996–2000) and was completed in 2000. The bridge is 52 metres (171 ft) high, and 1,504 metres (4,934 ft) long. It connects Paramaribo with Commewijne, a connection which previously could only be made by ferry. The purpose of the bridge was to facilitate and promote the development of the eastern part of Suriname. The bridge consists of two lanes (one lane each way) and is not accessible to pedestrians.

The construction of the Sts. Peter and Paul Cathedral started on 13 January 1883. Before it became a cathedral it was a theatre. The theatre was built in 1809 and burned down in 1820.

Suriname is one of the few countries in the world where a synagogue is located next to a mosque. The two buildings are located next to each other in the centre of Paramaribo and have been known to share a parking facility during their respective religious rites, should they happen to coincide with one another.

A relatively new landmark is the Hindu Arya Diwaker temple in the Johan Adolf Pengelstraat in Wanica, Paramaribo, which was inaugurated in 2001. A special characteristic of the temple is that it does not have images of the Hindu divinities, as they are forbidden in the Arya Samaj, the Hindu movement to which the people who built the temple belong. Instead, the building is covered by many texts derived from the Vedas and other Hindu scriptures. The architecture makes the temple a tourist attraction.

See also

Notes

- Both French Guiana and Falkland Islands are less extensive and populous, but they are an overseas department and region of France and an overseas territory of the United Kingdom respectively.

- Suriname has been carbon negative since at least 2014.

- The International Organization for Migration made a confusion regarding the number of Surinamese migrants living in French Guiana. Their number is already included in the number for France (24,753 at the time of writing), as can be seen here: données complémentaires.

References

- Suriname: An Asian Immigrant and the Organic Creation of the Caribbean's Most Unique Fusion Culture, archived from the original on 20 February 2017, retrieved 19 July 2017

- "Censusstatistieken 2012" (PDF). Algemeen Bureau voor de Statistiek in Suriname (General Statistics Bureau of Suriname). p. 76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2014.

- "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. 29 September 2021.

- ^ Algemeen Bureau voor de Statistiek. "Geselecteerde Census variabelen per district (Census-profiel)" (PDF). ABS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ "Census statistieken 2012". Statistics-suriname.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ "Definitieve Resultaten (Vol I) Etniciteit". Presentatie Evaluatie Rapport CENSUS 8: 42.

- ^ "2012 Suriname Census Definitive Results" (PDF). Algemeen Bureau voor de Statistiek – Suriname. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Suriname". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022. (Archived 2022 edition.)

- ^ "Suriname country profile". BBC News. 23 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Suriname)". International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- Nations, United (13 March 2024). Human Development Report 2023-24 (Report). United Nations.

- "GINI index". World Bank. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- "Suriname". Central Intelligence Agency. 29 November 2023 – via CIA.gov.

- "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Suriname". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- "Taalonderzoek in Nederland, Vlaanderen en Suriname (2005)". taal:unie. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- "Suriname", The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 5. Edition 15, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2002, p. 547

- Patte, M.-F. (2010). "Arawak vs. Lokono". In a Sea of Heteroglossia: 1–10.

- ^ Oudschans Dentz, F. (1919–1920). "De Naam Suriname". De West-Indische Gids. 1st Jaarg (Tweede Deel): 13–17. doi:10.1163/22134360-90001870. ISSN 1382-2373. JSTOR 41847495. S2CID 194102071.

- ^ Baynes, Thomas Spencer (1888). Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume XI (Ninth Edition—Popular Reprint ed.).

In 1614, the states of Holland granted to any Dutch citizen a four years' monopoly of any harbour or place of commerce which he might discover in that region (Guiana). The first settlement, however, in Suriname (in 1630) was made by an Englishman, whose name is still preserved by Marshall's Creek.

- Menon, P.K. (October 1978). "International Boundaries: A Case Study of the Guyana-Surinam Boundary". The International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 27 (4): 738–768. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/27.4.738. JSTOR 758476.

- Wilkie, Lieutenant-Colonel (1841). The United Service Journal and Naval and Military Magazine. p. 205.

Coming from the south we pass Surinam, the original name of which was Surryham, so called after Lord Surry, in the time of Charles II., and since corrupted to Surinam.

- Badoe, Etta (11 November 2015). "1664 New Amsterdam becomes New York Dutch rulers surrender to England". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Streissguth, Tom (2009). Suriname in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-57505-964-8.

- Boxer, C.R. (1990). The Dutch Seaborne Empire. Penguin. pp. 271–272. ISBN 978-0140136180.

- Simon M. Mentelle, "Extract of the Dutch Map Representing the Colony of Surinam", c.1777, Digital World Library via Library of Congress. Retrieved 26 May 2013

- Douma, Michael J. (2015). "The Lincoln Administration's Negotiations to Colonize African Americans in Dutch Suriname" (PDF). Civil War History. 61 (2): 111–137. doi:10.1353/cwh.2015.0037. S2CID 142674093.

- "Suriname View Geschiedenis". 30 July 2020.

- "Suriname Country Profile". BBC News. 14 September 2012.

- "Multicultural Netherlands". UC Berkeley. 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- World War II Timeline. Faculty.virginia.edu. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- "Tweede wereldoorlog". TRIS Online (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- Maurice Blessing (October 2013). "Wilhemina preekt de revolutie" (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- Obituary, The Guardian, 24 January 2001.

- Vezzoli, Simona (November 2014). "The evolution of Surinamese emigration across and beyond independence: The role of origin and destination states" (PDF). IMI Working Papers Series. International Migration Institute (IMI), University of Oxford. DEMIG project paper 28.

- "Foreign Relations, 1977–1980, Volume XXIII, Mexico, Cuba, and the Caribbean – Office of the Historian".

- Roger Janssen (1 January 2011). In Search of a Path: An Analysis of the Foreign Policy of Suriname from 1975 to 1991. BRILL. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-90-04-25367-4.

- Betty Sedoc-Dahlberg. "Refugees from Suriname". Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "Bouterse heeft Daal en Rambocus doodgeschoten". Network Star Suriname, Paramaribo, Suriname. 23 March 2012.

- "Panorama de la population immigrée en Guyane" (PDF). INSEE. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Neilan, Terence (17 July 1999). "World Briefing". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Suriname ex-strongman Bouterse back in power, In: BBC News, 19 July 2010

- Suriname's Bouterse Secures Second Presidential Term, Voice of America News, 14 July 2015

- The Associated Press (29 November 2019). "Suriname President Convicted in 1982 Killings". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "VHP grote winnaar verkiezingen 25 mei 2020". GFC Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Breaking: NDP dient geen lijst in". Dagblad Suriname (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Live blog: Verkiezing president en vicepresident Suriname". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Inauguratie nieuwe president van Suriname op Onafhankelijkheidsplein". Waterkant (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- Kuipers, Ank (18 February 2023). "Protesters storm Suriname's parliament as anti-austerity rally turns chaotic". Reuters.

- "Suriname: Government". The World Factbook. 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "The Netherlands and Suriname are closely linked". MinBuZa.nl. 18 November 2011. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- "Holland to redefine relationship with Suriname". Jamaica Gleaner. 23 March 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- "Suriname". US Department of State. 3 September 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- 50 Years of Singapore and the United Nations. World Scientific. 2015. ISBN 978-981-4713-03-0.access-date=28 March 2024

- "European Union – EEAS (European External Action Service) | EU Relations with Suriname". Europa (web portal). 19 June 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- "STATEMENT BY THE RIGHT HONOURABLE OWEN S. ARTHUR, PRIME MINISTER, BARBADOS, ON THE OCCASION OF THE SIGNING OF THE AGREEMENT FOR THE DEEPENING OF BILATERAL COOPERATION BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF BARBADOS AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SURINAME, 17 FEBRUARY 2005, PARAMARIBO, SURINAME". Caribbean Community (CARICOM). 17 February 2005. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- Agreement for the Suriname-Barbados Joint Commission. foreign.gov.bb. 13 March 2009

- "BGIS Media – Press Releases – Second Meeting of the Barbados/Suriname Joint Commission". Gisbarbados.gov.bb. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Erthal Abdenur, Adriana (2013). "South-South Cooperation in Suriname: New Prospects for Infrastructure Integration?" (PDF). Integration and Trade. 36 (17): 95–104. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Discover Suriname. "About Suriname | Discover Suriname". www.discover-suriname.com.

- "Suriname at GeoHive". Geohive.com. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- Permanent Court of Arbitration – Guyana v. Suriname Archived 8 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Award of the Tribunal Archived 2 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. pca-cpa.org. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- "Suriname's climate promise, for a sustainable future". UN News. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Suriname". inaturalist.org.

- Cocoa frog and lilliputian beetle among 60 new species found in Suriname. The Guardian (3 October 2013). Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- New species discovered in Surname's mountain rainforests. The Telegraph (2 October 2013). Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Scientists discover scores of species in Suriname's 'Tropical Eden'. NBC News (7 October 2013). Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- New-Species Pictures: Cowboy Frog, Armored Catfish, More. National Geographic (1 January 2012). Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Discover 60 New Species In Suriname. The Huffington Post (3 October 2013). Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Law Compliance, and prevention, and control of illegal activities in the forest sector of Suriname, Maureen Playfair

- Suriname gets the nod for environment programme – News – Global Jamaica. Jamaica-gleaner.com (25 March 2013). Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- "Guardians of the Forest: Indigenous Peoples Take Action to Conserve Nearly Half of Suriname", 5 March 2015, Press Release, Conservation International. Retrieved 6 October 2016

- UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre World Databbase on Protected Areas Archived 4 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Suriname's climate promise, for a sustainable future". UN News. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Overheidsinkomsten uit goudsector stijgen dit jaar verder". Dagblad Suriname (in Dutch). 4 October 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- "Starnieuws - Column: De bijdrage van goud aan de economie van Suriname". m.starnieuws.com. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- "Gold production". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 29 November 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- "Staatsolie - Suriname's National Energy, Oil & Gas Company - AGM Approves 2022 Financial Statements; Contribution of US$ 320 million to the State treasury". www.staatsolie.com. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- "De West - STAATSOLIE DRAAGT ENORM BIJ AAN STAATSKAS - DE WEST". dagbladdewest.com. 25 June 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- "Staatsolie draagt US$ 335 miljoen bij aan de staatskas in 2023 | Suriname Nieuws Centrale". surinamenieuwscentrale.com (in Dutch). 7 May 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- rigzone.com; Staatsolie Launches Tender for 3 Offshore Blocks (3 January 2006)

- cambior.com; Development of the Gross Rosebel Mine in Suriname.

- "Suriname – Foreign trade". Encyclopedia of the Nations. 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- The Economist, Pocket World in Figures, 2008 Edition, London: Profile Books

- "World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations". population.un.org. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- "World Population Review". 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- "South America :: SURINAME". CIA The World Factbook. 17 May 2022.

- Suriname: An Asian Immigrant and the Organic Creation of the Caribbean's Most Unique Fusion Culture, archived from the original on 20 February 2017, retrieved 19 July 2017

- "Censusstatistieken 2012" (PDF). Algemeen Bureau voor de Statistiek in Suriname (General Statistics Bureau of Suriname). p. 76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2014.

- "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Census statistieken 2012". Statistics-suriname.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- "Definitieve Resultaten (Vol I) Etniciteit". Presentatie Evaluatie Rapport CENSUS 8: 42.

- (in Indonesian) Orang Jawa di Suriname (Javanese in Suriname), kompasiana (14 March 2011)

- "Violence erupts in Surinam Archived 2 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 26 December 2009.

- International Organization for Migration. "World Migration". Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ "Suriname". Global Religious Futures Project. Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- "Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project – Research and data from Pew Research Center". 19 August 2024.

- "Het Nederlandse taalgebied" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Taalunie. 2005. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- (in Dutch) Nederlandse Taalunie. taalunieversum.org

- Prisma Woordenboek Surinaams Nederlands, edited by Renata de Bies, in cooperation with Willy Martin and Willy Smedts, ISBN 978-90-491-0054-4

- Romero, Simon (23 March 2008). "In Babel of Tongues, Suriname Seeks Itself". The New York Times.

- "Suriname - Summary". Climate Change Knowledge Portal. World Bank Group. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- "Biggest Cities Suriname". www.geonames.org.

- "National Holidays – the Embassy of the Republic of Suriname in Belgium".

- "Holiday Calendar". U.S. Embassy in Suriname. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- "Eid-ul-Adha vrije dag". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "A Sabbatical in Suriname – Fun Facts, Questions, Answers, Information". Funtrivia.com. 25 February 1980. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- "Het debuut van Humphrey Mijnals". Olympisch Stadion. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- Iris Jharap player profile and statistics – ESPNcricinfo. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Het blijft bij één keer brons op Cacso| Radio Nederland Wereldomroep. Rnw.nl (27 September 2012). Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Results And Medalists Archived 4 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. London2012.com. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Starnieuws, Hall of Fame na twaalf jaar een feit geworden, 6 November 2016 (in Dutch)

- In Suriname's Rain Forests, A Fight Over Trees vs. Jobs, Anthony DePalma, The New York Times, 4 September 1995

- ^ New Scientist Archived 8 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, 25 December 1986 – 1 January 1987, page 18

- The Rule of the Road: An International Guide to History and Practice, Peter Kincaid, Greenwood Press, 1986, page 138

- "Suriname – The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- "Suriname Transport Facts & Stats". www.nationmaster.com. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- "American Airlines Becomes the Only US Carrier with Nonstop Service from Miami to Tel Aviv and Paramaribo, Suriname". news.aa.com. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- "GBD Compare | IHME Viz Hub". vizhub.healthdata.org. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "The UN Refugee Agency". Unhcr.org. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "United Nations Development Programme". Hdrstats.undp.org. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- De Koninck, Marc; de Vries, Ellen (2008). K'ranti! De Surinaamse pers 1774–2008 (PDF). pp. 235–243.

- Press Freedom Index 2011–2012 – Reporters Without Borders Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Reports Without Borders. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- "Surinaamse Broedergemeente stapt in ecotoerisme". Reformatorisch Dagblad (in Dutch). Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Tonka-eiland Saramaccaans kennis-centrum en Eco-toeristisch paradijs". Tonka-Eiland. 2009. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- Brouns, Rachelle (February 2011). "People in the beating heart of the Amazon" (PDF). Radboud university Nijmegen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "OSAC". osac.gov. 2018.

- Down Suriname Way, a Tiny Community of Jews Endures, Tablet, 8 December 2014

Further reading

- Box, Ben, Footprint Focus Guide: Guyana, Guyane & Suriname (Footprint Travel Guides, 2011)

- Briggs, Philip, "Suriname, 2nd Ed.", (Bradt Guides, 2020)

- Counter, S. Allen and David L. Evans, I Sought My Brother: An Afro-American Reunion, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1981

- Dew, Edward M., The Trouble in Suriname, 1975–93, (Greenwood Press, 1994)

- Gimlette, John, Wild Coast: Travels on South America's Untamed Edge (Profile Books, 2011)

- McCarthy Sr., Terrence J., A Journey into Another World: Sojourn in Suriname, (Wheatmark Inc., 2010)

- Westoll, Adam, Surinam, (Old Street Publishing, 2009)