| Eumenes of Cardia | |

|---|---|

Gold stater (319-317 BC) of the Macedonian mint at Susa. Eumenes struck the coin to fund his war against Antigonus I Monophthalmus. Athena depicted left, Nike depicted right. Gold stater (319-317 BC) of the Macedonian mint at Susa. Eumenes struck the coin to fund his war against Antigonus I Monophthalmus. Athena depicted left, Nike depicted right. | |

| Native name | Εὐμένης |

| Born | 361 BC Cardia (near the Gulf of Saros, Turkey) |

| Died | winter of 316-315 BC (aged 45) Gabiene, Persia (modern-day Iran) |

| Cause of death | Strangulation (Execution) |

| Allegiance | Macedonian Empire Argead Dynasty |

| Rank | Personal secretary General Satrap of Cappadocia and Paphlagonia |

| Battles / wars | |

| Spouse(s) | Artonis, daughter of Achaemenid satrap Artabazus II |

Eumenes (/juːˈmɛniːz/; Ancient Greek: Εὐμένης; fl. 361–315 BC) was a Greek general, satrap, and Successor of Alexander the Great. He participated in the Wars of Alexander the Great, serving as Alexander's personal secretary and later on as a battlefield commander. Eumenes depicted himself as a lifelong loyalist of Alexander's dynasty and championed the cause of the Macedonian Argead royal house.

In the Wars of the Diadochi after Alexander's death, Eumenes initially supported the regent Perdiccas in the First Diadochi War, and later the Argead royalty in the Second Diadochi War. Despite less experience as a commander, Eumenes defeated Craterus, one of Alexander's most accomplished generals, at the Battle of the Hellespont in 321 BC. After Perdiccas' murder in 320 BC Eumenes became a public enemy of the new Post-Alexander regime under Antipater and Antigonus. In 319 BC he was defeated by Antigonus at the Battle of Orkynia and confined to Nora.

Eumenes escaped and then allied with Polyperchon and Olympias, Alexander's mother, against Cassander and Antigonus. From 318 BC onward he led a hard-fought campaign against Antigonus, defeating him at the Battle of Paraitakene, then being indecisively defeated later at the Battle of Gabiene. Afterward, Eumenes was betrayed by his soldiers (the Silver Shields) and given over to Antigonus. Antigonus executed him in the winter of 316–315 BC.

The Greek biographer and essayist Plutarch chose Eumenes as the focus of one of his biographies in Parallel Lives, where he was paired with Quintus Sertorius, the rebel Roman general who led a revolt against Rome in the 70s BC.

Early career

Eumenes was a native of Cardia in the Thracian Chersonese. His father, a prominent citizen of Cardia, was named Hieronymus. Hieronymus cultivated a friendship with Philip II of Macedon which eventually led Eumenes to be employed as a private royal secretary (grammateus) by Philip, probably in 342 BC. He may have sought refuge in Macedonia because of the tyrant Hecataeus of Cardia's enmity toward his family.

Eumenes also impressed Alexander's mother, Olympias, who later called him "the most faithful of my friends". Despite the position of secretary being looked down on by Macedonians, Eumenes held significant authority in the office, as he oversaw all written communications and maintained a close relationship with the king.

Eumenes served as hetairos (companion and cavalry captain) and royal secretary under both Philip and Philip's successor, Alexander the Great. After Philip's death (336 BC) Eumenes remained loyal to Alexander and Olympias and accompanied Alexander into Asia, but for most of his reign served as royal secretary. Eumenes did not get along with Hephaestion, Alexander's closest companion, repeatedly arguing with him over "trivial matters". Plutarch also reports an anecdote of Eumenes hiding money from Alexander.

After Alexander's victory at the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC, Eumenes began performing military and diplomatic missions, such as his pronouncement to Sangala in 326. He may have played a larger part in Alexander's eastern campaign, especially in India, than the surviving accounts say. Eumenes was promoted to leader of the companion cavalry (hipparch), formerly held by Perdiccas following Hephaestion's death in late 324 BC. Eumenes also participated in the Marriages at Susa in 324 BC with the other hetairoi. Eumenes wed Artonis, daughter of Persian satrap Artabazus II and sister of Pharnabazus III, Persian satrap of Phrygia. This was a high honour as Artonis' sister was Barsine, a mistress of Alexander and mother of his son Heracles of Macedon.

By the time Alexander had defeated the Achaemenid Persian Empire, Eumenes was the "shrewd administrator" and secretary for Alexander's domain, deeply involved in day-to-day affairs. Eumenes is recorded as an author of the Ephemerides, a chronicle of Alexander the Great's activities leading up to his illness and death.

After the death of Alexander the Great

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, Eumenes was left with less standing, since his position depended closely on the king. Alexander had left no apparent heir. When Alexander's leading officers (somatophylakes and others) and a mass of infantry were debating whether one of the living Argeads should ascend or a regency should be installed for Alexander's unborn child (Alexander IV), Eumenes was present alongside the officers but did not speak. When the officers fled Babylon in the ensuing riot of the infantry, Eumenes remained in the city to make Meleager (the leader of the disgruntled infantry) come to an agreement with the officers.

Eumenes used his Cardian heritage to argue he had no personal motivation in the "Macedonian" struggle. The infantry were willing to listen to Eumenes because of his close association with Alexander. The officers eventually subdued Meleager and regained control over Babylon by announcing a joint kingship between Philip III Arrhidaeus and, when he was born, Alexander IV. Perdiccas became regent, effective ruler of the vast Asian section of Alexander's Empire, and Eumenes served as his advisor. Eumenes procured Alexander's "Last Plans" and gave them to Perdiccas, who read them out before the soldiers before rejecting them.

Satrap of Cappadocia and Paphlagonia (323–319 BC)

Main article: Partition of BabylonAlexander's Empire was split in the Partition of Babylon (323 BC), where Cappadocia and Paphlagonia were assigned to Eumenes, but they were not yet subdued. The Achaemenid satrap Ariarathes still held Cappadocia, and the Paphlagonian tribes had renounced allegiance to the Macedonian government. Eumenes thus had to subdue these forces to actually attain his satrapy. Perdiccas used his authority as regent of the joint kings to order Leonnatus, satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia, and Antigonus, satrap of Phrygia, Pamphylia and Lycia, to aid Eumenes in securing his satrapy. Eumenes left Babylon in the late summer of 323 BC.

Eumenes was probably given 5000 talents of gold from Perdiccas for the reconquest of Cappadocia. Leonnatus accompanied him, but Antigonus ignored Perdiccas' order. Eumenes arrived in Cappadocia and began to hire mercenaries. Leonnatus, however, was requested by Hecataeus of Cardia to march west to relieve Antipater who was besieged at Lamia as part of the Lamian War. Leonnatus agreed to go west, as he had received letters from Cleopatra of Macedon (daughter of Olympias, sister of Alexander the Great) asking him to marry her and become king of Macedon.

Leonnatus attempted to induce Eumenes to reconcile with Hecataeus and accompany him to Macedon to share in his far-reaching designs. Eumenes refused, fearing Antipater would murder him if he returned, and felt " to abandon his standing with Perdiccas for a mad and dangerous dash to Macedonia". He told Leonnatus he would give his answer later, then fled back to Perdiccas early in 322 BC, telling the regent of Leonnatus' plans. For this, Perdiccas elevated Eumenes to the ruling council of the Empire.

Eumenes joined Perdiccas, who installed him in Cappadocia by defeating and killing Ariarathes in the summer of 322. Eumenes reorganized his satrapy and appointed his supporters to prominent positions. The two generals traveled to Cilicia by autumn. Eumenes then returned to Cappadocia to aid Neoptolemus (satrap of Armenia) in his efforts to subdue the Satrapy of Armenia. Neoptolemus' soldiers, disgruntled with authority, refused to listen to Eumenes just as they had refused Neoptolemus. Eumenes subdued them by raising 6300 cavalry from Cappadocia, and made his satrapy peaceful and loyal by giving the Cappadocians monetary concessions. Eumenes probably successfully campaigned in Armenia throughout 322 and 321 BC.

The arrival of Cleopatra and war

Main article: First War of the DiadochiIn the spring of 321 BC, Nicaea (daughter of Antipater) and Cleopatra of Macedon both came to Perdiccas and offered themselves as his bride. Eumenes may have played a role in Cleopatra's arrival; when she arrived, he championed her proposal over that of Nicaea. Eumenes' advice carried weight as the common soldiers respected him after his pacifying of Armenia.

Perdiccas married Nicaea, but when his control over Philip III was challenged by Eurydice, he sent Eumenes to Cleopatra to reopen negotiations for marriage. Antigonus fled to Macedonia, and informed Antipater of Perdiccas' intentions to divorce his daughter Nicaea and marry Cleopatra. Craterus and Antipater, having subdued most of Greece in the Lamian War, were infuriated by Antigonus' news. They suspended their plans for more campaigns in Greece and prepared to pass into Asia and depose Perdiccas.

Asia Minor and the Hellespont

Main article: Battle of the Hellespont (321 BC)Perdiccas and his government decided to attack Egypt, as Ptolemy had, through the help of a Perdiccan officer, obtained Alexander the Great's funeral carriage. Eumenes, in turn, was given supreme command (as autokrator) in Asia Minor to beat back Antipater and Craterus who were mustering armies in Greece.

Eumenes marched to the Hellespont, following orders to defend it, and spoke to Cleopatra again at Sardis, who this time refused to marry Perdiccas, uncertain of who would win in the war to come. Antigonus, who sailed over with a fleet and landed in western Asia Minor, succeeded in winning over many satraps and cities (Asander of Caria, Menander of Lydia, among others). Eumenes narrowly escaped capture in Sardis thanks to Cleopatra's warning. Eumenes then retreated inland as Cleitus the White defected with his fleet (allowing Craterus and Antipater to cross), and Perdiccas, hearing of these disasters, ordered Neoptolemus and Alcetas to obey him. Both of these Macedonian officers resented Eumenes, and refused to do so.

Eumenes received messages from Craterus and Antipater once they had reached Asia Minor, promising to retain him in his satrapy if he joined them. Craterus wanted to reconcile Eumenes with Antipater, while Eumenes wanted to reconcile Craterus with Perdiccas; negotiations failed however, as Eumenes stayed loyal to Perdiccas, and Craterus to Antipater. Eumenes then discovered Neoptolemus was planning to defect to Craterus and Antipater, and defeated him in battle in Phrygia, recruiting much of his army. Neoptolemus fled to Craterus and Antipater with 300 horsemen, and convinced them to march: soon after, Craterus took the majority of the Macedonian army to confront Eumenes.

Despite possessing far lower quality infantry than Craterus, Eumenes accepted the offer of battle, believing in his superior cavalry, beginning the Battle of the Hellespont. Eumenes concealed Craterus' name from his soldiers, knowing his popularity would sway their loyalty, instead claiming the Asian warlord "Pigres" had joined Neoptolemus and was marching against them. Eumenes also proclaimed he had received a dream that his army would be victorious. During the battle, Eumenes prevented any Macedonians from recognizing the popular Craterus through his troop placement and tactics, and as a result Craterus was killed, his flank overran by Eumenes' Cappadocian cavalry. Eumenes, leading the left flank, killed Neoptolemus in single combat, then induced the enemy infantry to surrender, winning a "stunning victory".

The victory brought Eumenes the enmity of some of his men due to his foreign heritage. He attempted to compel Craterus' infantry phalanx to desert to him, but failed and the infantry hastily marched south to link up with Antipater. News of Eumenes' victory, which might have restored Perdiccas' authority, reached Egypt only one day after Perdiccas was assassinated by his men in a mutiny (320 BC).

After the death of Perdiccas and Triparadisus

After the murder of Perdiccas in Egypt, the Macedonian generals condemned Eumenes (and the other Perdiccans) to death at the Conference at Triparadisus, with Antipater assigning Antigonus as his chief executioner. Eumenes' province of Cappadocia was officially transferred to Nicanor, and Antigonus was given a large army to destroy the remaining Perdiccans in Asia. Eumenes was now in "far worse circumstances than he had been at Alexander's death" as he was an outlaw and being actively hunted, but he had an experienced, loyal army and prepared for the coming conflict with Antigonus.

Following Triparadisus, Antigonus placed a bounty on the Greek general's head of 100 talents of gold. News of this came immediately after Eumenes' financial rewards, so his officers and men were outraged and redoubled their efforts to protect their leader, assigning a large bodyguard of 1000 men to protect him at all times. He was also given the privilege of granting purple hats and cloaks to his soldiers, an honour usually only allowed for a Macedonian king. Eumenes further consolidated loyalty by arguing to his men that the joint kings had been taken by traitors to the Macedonian throne and that, in effect, he and his army were still loyalists to the Argead house.

Eumenes first travelled to Mount Ida where there was a royal stable, and took a large number of horses to replenish his Cappadocian cavalry. He took the time to file an account with the overseers of the stables despite his outlaw status. Upon hearing this, Antipater was greatly amused, however, it is clear that Eumenes made this move to show that he was acting under the law and in the service of the Argead House.

Eumenes marched to the Hellespont, where he quartered his army and plundered the locals who refused to pay his soldiers. He "continued to demonstrate his prowess as a military commander," attacking Hellespontine Phrygia and Phrygia itself while Antigonus and Antipater were present (on their return trip to Macedonia). Since he would be facing a force superior in infantry, Eumenes decided to position himself in the plains of Sardis of Lydia where his advantage in cavalry would be decisive. To further guarantee the loyalty of subordinates, Eumenes also sold off the estates of Phrygia to them and provided military support to claim the purchased land from the, obviously, unwilling and disgruntled Phrygian property owners. This revenue was used to pay his soldiers.

He had also hoped to win the support of Cleopatra of Macedon, who was present in Sardis at the time. Cleopatra and Eumenes had been friends since childhood, however, Cleopatra was not willing to back what seemed to be a losing cause and implored Eumenes to leave the area lest she incur the wrath of Antipater. Eumenes obliged her and moved north into Phrygia to winter. Eumenes' plundering campaigns during this time were very successful, so much so that Antipater's soldiers began to become disgruntled. Eumenes spent the winter of 320/319 BC in Celaenae.

In the winter, Eumenes sent messages to the other Perdiccan leaders, including Alcetas and Attalus (Perdiccas' brother-in-law), imploring them to unite their forces against Antigonus. A conference was held with the Perdiccan leaders in Celaenae: Eumenes argued that Antipater and Antigonus were unpopular, and that a united offensive would not only prove successful but also attract many deserters. Negotiations broke down, however, as neither Eumenes nor Alcetas would serve the other, and other commanders contested the chief position. Eumenes also dealt with a defection of 3500 of his men this winter; he executed the leaders and pardoned the soldiers.

When Eumenes' Macedonian generals approached him about one of them taking overall command, Eumenes is said to have retorted that "formalities and technicalities would not protect them from death and destruction".

Battle of Orkynia

Main article: Battle of OrkyniaIn 319 BC, Antigonus marched his army into Cappodocia and engaged Eumenes at the Battle of Orkynia; Eumenes accepted the battle as the ground was advantageous for cavalry. Eumenes was easily defeated due to the mid-battle desertion of a mercenary cavalry officer named Apollonides, who Antigonus had bribed. Antigonus may have also used a ruse (pretending he received reinforcements) to discourage Eumenes' men before the battle. Although defeated, Eumenes swiftly acted to chase down and execute Apollonides, which restored the faith of his men.

Eumenes was put to flight, however, having lost some 8000 men, and moved toward Armenia. Antigonus pursued Eumenes and forced him to move carefully. Following the battle, Antigonus had neglected to address the dead and had immediately set off in pursuit for Eumenes. Determined to follow tradition, Plutarch reports that Eumenes made the unexpected move of returning to the battlefield so that he could construct a proper funeral pyre for the dead. This action greatly impressed Antigonus.

Remainder of the campaign

The remainder of the campaign turned into a battle of manoeuvre, with Eumenes avoiding further battle with Antigonus. At one point, Eumenes was in a position to capture the baggage of Antigonus' forces. Eumenes knew that he would not be able to prevent his soldiers from plundering this loot if they found out about it and also that doing so would decrease the essential mobility of his forces. Eumenes dispatched a private message to his old friend, the general Menander, advising him to move the baggage uphill so that its capture would be impossible. Menander immediately followed this advice. Eumenes feigned disappointment to his men and moved on. Menander and the other Antigonid officers were shocked by Eumenes' warning; only Antigonus knew of his actual motives.

Eumenes was pursued by Antigonus for several weeks until the following winter. He used guerrilla warfare to hold off Antigonus, but his men were deserting him. In the late spring of 319 BC, Eumenes disbanded his army, save for a small, crack force of 600 men and holed up in Nora, a strong and well-supplied fortress on the border between Cappadocia and Lycaonia. Antigonus arrived shortly after and decided to enter into negotiation with Eumenes instead of undergoing a lengthy siege.

Eumenes required Antigonus to send hostages to Nora before he was willing to come out and negotiate. Antigonus wanted to acquire Eumenes as his own officer and so first demanded that Eumenes address him as a superior officer. Eumenes refused, replying:

While I am able to wield a sword, I shall think no man greater than myself.

Despite their appointed role as enemies, Antigonus and Eumenes were actually old friends, and when they met they renewed their friendship, speaking amiably to one another. Eumenes' demands for surrender were that he retain Cappadocia as his satrapy and his status as outlaw be rescinded. Antigonus completed his siege constructions around Nora (blockading Eumenes in) and said he would ask the regent Antipater to confirm Eumenes' demands. Eumenes, overall unsatisfied after the long conference, was willing to hold out longer for a more favourable position in the imperial hierarchy. Antigonus departed with his army to confront the remaining Perdiccans, who were led by Alcetas and Attalus in Pisidia, whom he defeated.

Eumenes kept the morale of his besieged men high by mingling with them regularly, aided, apparently, by his friendly appearance. In the cramped city, he was forced to come up with novel solutions so that his men and horses remained in fighting shape including; emptying large rooms where men exercised on a set schedule, and creating a suspension device, likened to an ancient treadmill, on which horses could run.

Eumenes sent envoys under his friend and countryman Hieronymus of Cardia to Antipater to negotiate his surrender, probably in the late summer of 319 BC. Nothing came of this, however. Eumenes effectively held out for more than a year until the death of Antipater threw his opponents into disarray.

The Second War of the Diadochi (319–315 BC)

Main article: Second War of the DiadochiAntipater had become regent since Triparadisus, when he acquired the joint kings from the dead Perdiccas. He had taken them to Macedonia, but after his death left the regency to his friend Polyperchon instead of his son Cassander. Cassander, therefore, allied himself with Antigonus, Lysimachus and Ptolemy as he prepared to confront Polyperchon. Following Antipater's death, Antigonus sent generous terms to Eumenes in Nora through Hieronymus of Cardia that were nearly the same as Eumenes' initial demands. Eumenes probably agreed to the terms in 318 BC, swore loyalty to Antigonus, and left Nora. Another, less probable account says that Eumenes escaped Nora by rewriting his oath of loyalty to the joint kings instead of Antigonus.

With Macedonia in disarray, Antigonus prepared to conquer outward, revolt against the joint kings, and expand his power. Polyperchon, in order to shore up his allies in the coming conflict with Cassander, had written to Olympias requesting help; Olympias, already in contact with Eumenes, now wrote to him for advice. Eumenes told her to wait and see what would happen. Soon after, in the late summer of 318 BC, Polyperchon wrote to Eumenes himself, requesting an alliance in the name of the joint kings.

Polyperchon said Eumenes could march to Macedonia and become guardian of the kings, or stay in Asia with supreme command over the region and remain "a protector of royalty" abroad. Furthermore, he promised Eumenes command over the Asian treasuries (Susa and Cyinda, which would allow Eumenes to hire many mercenaries) and the allegiance of the formidable Silver Shields, highly skilled veterans who had fought with Alexander for years, if he accepted.

Eumenes decided to accept Polyperchon's offer, either out of a wish to protect the Argead royalty and Olympias, because of his own ambition and disinclination to be subordinate to another, or a combination of both factors. Eumenes' acceptance meant the war in Asia with Antigonus would start once again.

Campaign in Cilicia and Syria

Eumenes acted quickly to muster his army and marched into Cilicia, evading an army Antigonus sent to capture him. In Cilicia he allied with Antigenes and Teutamus, the commanders of the famous Silver Shields, the same men who had once condemned him to death after Perdiccas' murder. Eumenes was able to secure control over the unruly commanders of the Silver Shields by playing on their undying loyalty to, and superstitious awe of, Alexander. He claimed that Alexander had visited him in a dream and told him that he would be present with them at every battle. Eumenes even went so far as to set up a tent for the late conqueror complete with a throne, diadem, and scepter. This "ingenious stratagem" consolidated Eumenes' control and placated his Macedonian officers, who felt that they were listening less to a Cardian foreigner and more to the late Alexander. As a result, Eumenes' orders were followed. Furthermore, Eumenes argued that as a Greek, a Cardian, "his only concern was the defence of the royal family".

Eumenes used the royal treasury at Cyinda to recruit an army of mercenaries to add to his own troops, a process that took several months but built up a sizeable army. Propaganda attempts by Ptolemy to subvert supporters of Eumenes in Asia, military and political, failed uniformly. Antigonus attempted this as well and successfully convinced Teutamus (one of two commanders of the Silver Shields) but Antigenes, the other, stayed loyal to Eumenes, ironically because of his foreign heritage. Eumenes emerged from Antigonus' propaganda campaign with a generally greater authority among his Macedonian troops.

In the winter of 318/317 BC, Eumenes left Cilicia and marched into Syria and Phoenicia, and began to raise a naval force on behalf of Polyperchon to sail to the Aegean Sea. Ptolemy, who had recently conquered the area, did not stop him. When it was ready in early August of 317 BC, Eumenes sent the fleet west to reinforce Polyperchon, but it changed sides after meeting Antigonus's fleet off the coast of Cilicia. Meanwhile, Antigonus had settled his affairs in Asia Minor and marched east to take out Eumenes before he could do further damage.

Polyperchon's campaign in Macedonia was failing, leaving Eumenes isolated; Eumenes himself, now knowing Antigonus was coming and that he could not help Polyperchon in Macedonia, marched out of Phoenicia in late August/early September, eastward through Syria into Mesopotamia, with the idea of gathering support in the upper satrapies, where there was currently conflict.

Campaign in the Upper Satrapies

Eumenes gained the support of Amphimachus, the satrap of Mesopotamia, then marched his army into Northern Babylonia. During the march he negotiated with Seleucus, the satrap of Babylonia, and Peithon, the satrap of Media, seeking their help against Antigonus. Seleucus replied that he would not obey someone condemned to death, and Peithon was similarly unwilling. Eumenes wintered north of Babylon in 317/316 BC, during which time he sent the letters he had gotten from Polyperchon to satraps of the upper satrapies. These letters ordered the satraps, in the kings' names, to join him with all their forces. The upper satraps had already united their armies under the leadership of Peucestas, satrap of Persis, to combat the expansionism of Peithon and were willing to join Eumenes.

Eumenes left his winter quarters early in the spring of 316 BC and marched on Susa, a major royal treasury, in Susiana. Seleucus and Peithon attempted to subvert the Silver Shields while Eumenes was in Babylonia, and when they failed flooded his camp. Eumenes drained the land and escaped, and Seleucus, unable to oppose him, signed a truce for his passage.

In Susiana, Eumenes joined the already assembled army of the upper satraps. With this combined army Eumenes' could confidently match Antigonus. Peucestas, however, argued that he deserved the high command due to his high standing and large army. Eumenes' problem of divided command was exacerbated by Peucestas and his companions, but they were again placated by Eumenes' Tent of Alexander, where communal meetings would be held to direct the war against Antigonus. In late May, Eumenes reached Susa and extensively paid and rested his troops, while also paying Eudamus for the support of his war elephant corps. When Antigonus arrived in Susiana, Eumenes ordered the treasurer Xenophilus of Susa not to give anything to Antigonus.

Eumenes then marched southeastwards into Persia, where he picked up additional reinforcements. He crossed the Pasitigris, where he planned to ambush Antigonus, knowing he would be crossing blind.

Battle of the river Coprates

Main article: Battle of the river CopratesAntigonus, meanwhile, had reached Susa and left Seleucus there to besiege the place while he himself pursued Eumenes towards the Pasitigris. Eumenes required more troops to block the entire river, and so asked Peucestas to recruit more; Peucestas initially refused to do so, resenting Eumenes, but eventually agreed. In the late July of 316 BC, Antigonus arrived at the river Coprates (a tributary of the Pasitigris) and prepared to cross. He sent an advance force ahead in boats to ensure a beachhead on the opposite side of the river. Eumenes, who had camped nearby and placed scouts across the breadth of the river to alert him, soon heard that Antigonus had sent over men and quickly rode over with an army.

Eumenes waited until the army was mid-crossing, and then surprised Antigonus' soldiers, easily routing them, capturing 4000 men while killing some 6000 others. Antigonus, whose soldiers were already struggling with the harsh temperatures, was faced with disaster. Effectively unable to cross with Eumenes' presence and victory, Antigonus abandoned the idea and turned back northward, moving up into Media and Badace, then to Ecbatana through a damaging forced march to rest his men.

This move, "a sign of just how desperate Antigonus was after this first defeat", left open a route west, to Asia Minor, for Eumenes. Eumenes and his staff wanted to march westward, cut Antigonus's supply lines and secure Asia Minor. If Eumenes had been able to move, Antigonus and his ally Cassander's position would have been greatly damaged, but the satraps, including Peucestas, refused to abandon their satrapies. Knowing that if he split his army off from the satraps it would be no match for Antigonus' superior force, Eumenes relented to their demands and remained in the east.

Stay in Persis

Following the Coprates, Eumenes marched southeast towards Persepolis over 24 days. As they were in Peucestas' home territory, the satrap hosted an enormous banquet and feast for all of Eumenes' army, successfully increasing his own popularity and further contesting Eumenes position as supreme commander. Eumenes, unwilling to confront the challenge to his authority openly, forged a letter reporting news from the west and had it widely circulated in his camp. Supposedly from the satrap of Armenia Orontes, the letter said that Olympias and Alexander IV had conquered Macedon, killed Cassander, and that Polyperchon was en route to Asia with a great army.

The forged letter was believed because Eumenes had composed it in Aramaic, the common language of the Persian Empire, and Orontes was a friend of Peucestas. This "clever trick" greatly bolstered Eumenes' position as royal general and reasserted his supreme command. Eumenes then acted against Peucestas' allies, summoning the satrap of Arachosia Sibyrtius to a show trial after seizing his baggage train, making him flee. To further assure the loyalty of his subordinates, Eumenes took large loans (400 talents total) from them "in the name of the kings, thus binding them to him as anxious creditors".

Eumenes departed Persis and set out toward Antigonus when he heard Antigonus had left Ecbatana and was marching through Media. Eumenes wanted to battle Antigonus while his army had high morale, but while entertaining his troops became sick. Eumenes halted the march as his soldiers lost morale, as they regarded Eumenes as their greatest commander. He slightly recovered, but was compelled to give over supreme command to Peucestas and Antigenes to lead the army north while Eumenes himself convalesced, being carried in a litter. Antigonus hastened to battle Eumenes' army while Eumenes was ill. Eumenes recovered, however, and when the armies were within a day or so of each other resumed overall command to meet Antigonus.

Battle of Paraitakene

Main article: Battle of ParaitakeneIn the late October or early November of 316 BC, the two armies met in southern Media, beginning the Battle of Paraitakene. For five days Eumenes and Antigonus skirmished but did not engage in battle. Antigonus, on the fifth day, again attempted to subvert the Silver Shields, who again refused; Eumenes praised them for their loyalty. Eumenes then learned from deserters that Antigonus was planning to break camp and move away, and guessed Antigonus wanted to relocate to the region of Gabiene. In response to this, Eumenes bribed mercenaries to pretend to defect to Antigonus and report that he planned to attack Antigonus' camp at night. Antigonus believed the mercenaries and delayed his march, preparing for battle, while Eumenes split his army and set out immediately, gaining a six to seven hour head start on Antigonus to Gabiene.

Antigonus learned he had been deceived and force marched to pursue Eumenes. He caught up to Eumenes by riding hastily with his cavalry, and forced Eumenes to array for battle by concealing the fact that the rest of his army had not caught up yet. After Antigonus had assembled his army, he engaged Eumenes.

Eumenes positioned his elite troops on his right flank, including the Silver Shields, and led the elite cavalry himself. He placed his war elephants and light infantry in a screen ahead of his heavy infantry. The formation was defensive as Eumenes did not want to attack Antigonus uphill. Peithon, sent by Antigonus against Eumenes' right cavalry, succeeded initially in confining them. In response Eumenes transferred troops to enlarge the flank and beat back Peithon, who fled; meanwhile Eumenes' Silver Shields were sharply victorious, routing the enemy phalanx. Antigonus, though now facing "annihilation", ignored advice to retreat and, observing a gap in the line between Eumenes' phalanx and his left flank cavalry, charged and routed them; Eumenes called back his victorious right flank in response.

Though both generals reformed their armies and prepared to continue the battle, it was approaching night and the armies were too tired and hungry to proceed. Eumenes wanted to stay at the battlefield and bury the dead, thus allowing him to claim victory, but his troops wanted to return to their baggage train; fearing that a refusal would give his rivals for supreme command more power, Eumenes marched away. "Antigonus, however, had no such fears", and he was able to regain the battlefield and bury the dead, while proclaiming victory.

Antigonus, whose casualties were more numerous, detained Eumenes' herald to finish burning his dead and obscure their amount. He then force marched his demoralized army to safety the next night. Eumenes returned to the battlefield and buried his own dead lavishly. He then settled into Gabiene while Antigonus, indecisively defeated, reached and rested in Media.

Interim to Gabiene

During the winter of 316–315 BC, Eumenes' army camp was very widely spread, either because of insubordination or lack of supplies. He had stationed sentries on the roads, but not along the freezing desert routes into Gabiene (Dasht-i Kavir, south east of Isfahan). Antigonus, learning of this, planned to march through the desert and surprise attack Eumenes, but he was observed by some locals who reported it to his opponents.

The satraps were alarmed by this, as Antigonus was four days away and it would take at least six days to assemble their army. Peucestas advised tactical retreat and withdrew his portion of the army to a remote area of Gabiene. Eumenes, however, successfully persuaded the satraps to remain by pointing out their troops would be well-rested while Antigonus' would be tired from traversing the desert, and told them of a plan which would give them enough time to assemble the whole army.

After the conference Eumenes had his troops light numerous fires in the mountains bordering the desert every day. This made it appear as though Eumenes' entire camp was on the desert border, and Antigonus, observing this, delayed his march to rest his men for what he assumed would be another pitched battle against Eumenes' whole army.

Through this strategy Eumenes was able to delay battle and assemble his scattered army, though Antigonus did eventually learn the truth behind the fires. Eumenes success in preventing this attack raised his position and led many of the soldiers to ask him to lead them alone. Antigonus, however, was able to attack Eudamus and his elephant corps (they had been slow in leaving camp) and successfully killed many cavalry before being driven off by reinforcements sent by Eumenes.

As the forces assembled Antigenes, Teutamus, and other prominent members of Eumenes' army began plotting to kill Eumenes after Antigonus was defeated. Eudamus learned of the conspiracy and warned Eumenes, who thought of fleeing but chose not to. Eumenes, who "was not a coward and obviously an individual confident in his own ability", may have believed that the battle was worth fighting, despite the risks, because of the possibilities if he was victorious. Eumenes destroyed his correspondence, wrote his will, and prepared for the coming battle.

Battle of Gabiene

Main article: Battle of GabieneA few days later both armies drew up for battle, beginning the Battle of Gabiene. In the battle, Eumenes placed himself with his elite troops on the left flank in order to face Antigonus himself, who had positioned himself on his right flank. Again, Eumenes screened his cavalry with elephants and light infantry skirmishers. Eumenes' strategy focused on his phalanx and the Silver Shields; he ordered Philip (satrap of Bactria, leading the weaker right Eumenid flank), one of his loyal supporters, not to engage the enemy. Eumenes had placed Peucestas and the other satrapal cavalry on his own flank, perhaps to ensure they followed his orders.

Antigenes sent a single horseman to the enemy phalanx who was to face the Silver Shields; the horseman shouted that " are sinning against your fathers, you degenerates, the men who conquered the world with Philip and Alexander!" This pronouncement apparently demoralized Antigonus' infantry, and was met with a cheer from Eumenes' troops; Eumenes then sounded the charge and his army marched forward.

As the battle began, Antigonus, noticing that the movement of the troops kicked up clouds of dust that obscured sight, sent a sizeable cavalry contingent behind Eumenes' army to seize his baggage camp, and successfully did so without Eumenes noticing. After the war elephants engaged one another, Eumenes' cavalry met the cavalry of Antigonus, which was led by Antigonus' son Demetrius.

Eumenes' left cavalry was defeated due to the sudden retreat of Peucestas and the satrapal horsemen, which led to panic and another 1500 cavalry retreating with him. This cavalry defeat was disastrous for Eumenes. He continued to struggle against Antigonus, leading his cavalry forward in a charge in an attempt to meet and kill Antigonus in single combat, but failing due to his inferior number of horsemen. Facing heavy losses and being vastly outnumbered, Eumenes eventually gave way and rode over to his right flank.

The Silver Shields, however, were again victorious, routing Antigonus' phalanx and inflicting mass casualties. Eumenes, noting that the enemy phalanx had been destroyed, attempted to regather his cavalry on the right flank for a final push. He had heard his baggage had been captured, but believed that if his united cavalry joined the Silver Shields a renewed offensive would not only reclaim the lost baggage, but rout Antigonus' army and claim their baggage as well. Peucestas and the satraps refused Eumenes' orders, withdrawing further away as night approached.

Antigonus then unsuccessfully attacked the Silver Shields, who were able to retreat by forming a square and marching off of the battlefield. He prevented Eumenes' cavalry from linking up with the Silver Shields, and Eumenes was forced to withdraw.

Betrayal and Death

The Battle of Gabiene was effectively as indecisive as the previous battle at Parataikene. Although Eumenes had inflicted significantly greater casualties, he lost control of his army's baggage; in addition to all the loot of the Silver Shields (treasure accumulated over 30 years of successful warfare including gold, silver, gems and other booty), the soldiers' women and children were taken as well.

Eumenes was now in a precarious position, as he had planned for victory or defeat, but not stalemate. He arrived at camp following the battle after the Silver Shields and satraps did, and a conference was held in the late evening. The satraps wished to retreat, but Eumenes wanted to battle again the next day, citing the fact that the cavalry were not greatly diminished and the Silver Shields' victory in the centre. Eumenes had reason to be optimistic about another engagement and may have been successful in persuading the army, but the Silver Shields themselves, though they blamed Peucestas for the inconclusive result of the battle, wished to get their baggage and families back and refused both options. The conference ended without a decision.

Teutamus, one of their commanders, then sent the request to Antigonus to trade for a return of the baggage; Antigonus responded that they give him Eumenes in return, and the Silver Shields agreed, arresting Eumenes and leading him to Antigonus. Anson believes Eumenes, though he knew of the plot against his life, believed his skills as a commander would "obviously" be necessary for another battle against Antigonus and was thus taken off guard when actually arraigned.

Eumenes, during his seizure, requested and was given permission to talk to the assembled army. According to Plutarch, Eumenes said:

What trophy, you vilest of all the Macedonians! what trophy could Antigonus have wished to raise over you, more than this which you yourselves are raising, by delivering up your general bound? Was it not base enough to acknowledge yourselves beaten, though you had the upper hand, merely for the sake of your baggage, as if victory dwelt among your possessions, and not upon the points of your swords; but you must also send your general as a ransom for that baggage? For my part, though thus led, I am not conquered; I have beaten the enemy, and am ruined by my fellow-soldiers. But I conjure you by Zeus, the god of armies, and the awful deities who preside over oaths, to kill me here with your own hands. If my life be taken by another, the deed will be still yours. Nor will Antigonus complain, if you take the work out of his hands; for he wants not Eumenes alive, but Eumenes dead. If you choose not to be the immediate instruments, loose but one of my hands, and that shall do my business. If you will not trust me with a sword, throw me, bound as I am, to wild beasts. If you comply with this last request, I acquit you of all guilt with respect to me, and declare you have behaved to your general like the best and most honest of men.

This speech apparently garnered sympathy from most of the army, but the Silver Shields, unconvinced, continued to lead Eumenes on, and they were able to do so without challenge. The war was thus at an end. Eumenes was given to Antigonus, who placed him under guard and held councils to decide his fate that lasted several days.

Plutarch and Nepos write that Eumenes grew confused why Antigonus did not kill him or set him free; when his jailkeeper replied that if Eumenes wanted death he should have died in battle, Eumenes is said to have retorted that he had not died in battle because he had never encountered an opponent stronger than himself.

Antigonus, supported by his son Demetrius and Nearchus the Cretan, was disinclined to kill Eumenes, but most of the council and his soldiers demanded his execution and so it was decided. Antigonus starved Eumenes for three days but finally sent an executioner to strangle him when he had to move camp. Eumenes' body was given to his friends to be burnt with honour, and his ashes were conveyed in a silver urn to his wife and children.

Legacy

Generalship

Despite Eumenes' undeniable skills as a general, he never commanded the full allegiance of the Macedonian officers in his army and died as a result. Eumenes was disliked by many of his Macedonian companions—certainly for his successes and supposedly for his non-Macedonian (in the tribal sense) background and prior office as Royal Secretary.

Eumenes is broadly seen as an excellent commander, skilled in both tactics and strategy and Antigonus' only military equal, who did his utmost to maintain the unity of Alexander's empire in Asia. He was also an "adept propagandist", who used diplomacy and ruse to his advantage wherever possible. Eumenes' efforts were repeatedly frustrated by issues of divided command and disloyal subordinates: his "most serious problem" which were handicaps many of his enemies, notably Antigonus, did not have to struggle with. Anson considers it "remarkable" that Eumenes came so close to defeating Antigonus, ultimately only losing through betrayal, given Antigonus' notable skill as a general and the repeated issues Eumenes dealt with.

Impact on the Age

Eumenes' defeat is seen as spelling the end for the Argead loyalists and, effectively, the Argead monarchy, leaving Alexander's Empire "in the hands of men who owed no loyalty except to themselves". Bosworth believes Eumenes' duel with Antigonus "did more than anything to define the shape of the Hellenistic world". Green concurs, writing that "With death... the fiction of the unified empire was exploded once and for all".

Romm writes that Eumenes "was the last general in the field with the ability, and will, to defend ", and that "through sheer talent Eumenes had risen through the ranks; despite his Greek origins, he had come desperately close to gaining supreme power". Eumenes has been seen as a tragic figure, a man who seemingly tried to do the right thing but was overcome by a more ruthless enemy and the treachery of his own soldiers; in essence, that he failed not due to any lack of ability, but from "ill luck, bad alliances, and one very capable opponent".

Historie is a historical fiction manga series that tells the life story of Eumenes.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/40812159 p.1 asserts they were struck in 317-316 BC, before the battles of Paraitakene and Gabiene in 315.

- Anson 2015, p. 41.

- Heckel 2006, p. 120; Anson 2015, p. 41; Nep., 13.1. Note; TroncosoAnson 2013, p. 105 dates Eumenes' death to the January of 315 BC.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 102; Heckel 2006, p. 120. Eumenes' motives are debated. Views are, generally, that Eumenes upheld the Argead cause either out of genuine loyalty, or due to opportunism. Ancient sources rather uniformly suggest Eumenes was a genuine royalist, and as cited some modern scholars agree, while Plutarch believes Eumenes waged war for the sake of power. Scholars who believe he was an opportunist argue that he remained loyal because; Bosworth 2005, p. 168, "he had no alternative but loyalty to the crown" if he wanted to pursue his own interests and retain power. Notably, unlike other Successors of Alexander, Eumenes was not Macedonian, and so could not inherently stake a claim to the throne; Anson 2015, the most authoritative source on the career of Eumenes, believes that "As with his contemporaries, Eumenes' first concern was his own self-interest, not any loftier ideals" and that Eumenes had an "all consuming" ambition for personal power (pp. 1, 205). Whatever his true motives, which are ultimately unknowable, Eumenes was essentially the last hope of the royals, and his defeat spelled their end as a powerful political force.

- Anson 2015, p. 42; Nep., 1.2-3: Eumenes was probably of very high birth.

- Heckel 2006, p. 120. Claims that his father was a waggoner or musician are probably false and invented to shame Eumenes, since these were considered unmanly professions. Generally; Anson 2015, pp. 41, 42 argues these may simply be another romantic (and false) "rags-to-riches" story.

- Anson 2015, pp. 42–43; Plut. Eum., 1.2.

- Nep., 1.5.

- Anson 2015, p. 43.

- Heckel 2006, p. 120; Anson 2015, pp. 51–53; Diod., 18.58.2. Anson believes this statement originates after Philip's death, when Olympias returned to Macedon and attacked her political rivals. Eumenes is said to have been "long hated" by Antipater, maybe because of the latter's hatred of Olympias or his support of Hecataeus; Plut. Eum., 3.4.

- Anson 2015, pp. 46, 57; Plut. Eum., 1.3, "Neoptolemus, the commander of the Shield-bearers, after Alexander's death, said that he had followed the king with shield and spear, but Eumenes with pen and paper,".

- Anson 2015, pp. 49, 52.

- Anson 2015, p. 51; Chisholm 1911.

- Anson 2015, p. 53.

- Plut. Eum., 2.1, 2.4.

- Anson 2015, p. 54 argues the enmity was personal, not political. After Hephaestion's death in 324, Eumenes praised him and contributed monetarily to his tomb construction to smooth over relations with Alexander.

- Plut. Eum., 2.2-3.

- Plut. Eum., 1.2.

- Anson 2015, p. 57.

- Romm 2011, p. 39; Heckel 2006, p. 120. Perdiccas himself was promoted to chiliarch, second in command to Alexander, the office Hephaestion held before his death.

- Anson 2015, p. 57, who believes Eumenes appointment could have been honorary or due to his skill in commanding cavalry.

- Diod., 17.107.

- Plut. Eum., 1.3. Plutarch gives her name as Barsine, but Arrian calls her Artonis..

- Green 1990, p. 9; Anson 2015, p. 46.

- Anson, Edward M. (1996). "The "Ephemerides" of Alexander the Great". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 45 (4): 501. ISSN 0018-2311.

- Anson 2015, p. 60.

- Anson 2015, p. 68. Eumenes was considered, apparently, one of "the chief and most influential commanders of the ".

- Waterfield 2011, p. 21.

- Anson 2015, p. 68; Romm 2011, p. 66; Waterfield 2011, p. 24; Plut. Eum., 3.1. Anson and Waterfield believe Eumenes did so in collusion with Perdiccas, who was leading the officers.

- Anson 2015, p. 69; Plut. Eum., 3.1.

- Plut. Eum., 1.3.

- Anson 2015, p. 78.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 11. Alexander apparently wanted to conquer all of northern Africa, Carthage, Spain, Sicily, and then Italy, and to accomplish this planned to found numerous cities and a war fleet of a thousand ships. Some scholars believe Perdiccas invented these plans to consolidate his authority as regent.

- Anson 2015, p. 78; Heckel 2006, p. 121.

- Anson 2015, p. 79; Plut. Eum., 3.2.

- Plut. Eum., 3.2.

- Anson 2015, p. 79.

- Anson 2015, p. 80.

- Plut. Eum., 3.3.

- Anson 2015, p. 82.

- Plut. Eum., 3.5.

- Anson 2015, p. 84; Heckel 2006, p. 121.

- Anson 2015, p. 84; Plut. Eum., 3.5.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 38.

- Anson 2015, p. 84.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- Anson 2015, pp. 86, 87; Plut. Eum., 3.7. Eumenes' broad authority in his satrapy is probably due to his loyalty to Perdiccas; the regent trusted him, and he was thus granted greater discretion and independence of action.

- Anson 2015, pp. 88, 89.

- Anson 2015, pp. 89, 90.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 91.

- Anson 2015, p. 91; Plut. Eum., 4.2, 4.3. Concessions as in lowered taxes and gifts of money. This incident, with the Greek Eumenes succeeding where the Macedonian Neoptolemus could not, may have begun the latter's hatred for Eumenes.

- Anson 2015, p. 94.

- Romm 2011, p. 169; Anson 2015, pp. 96–97, who suggests that Eumenes support for Cleopatra was not out of royal loyalty, but because he did not want Perdiccas to become allied to his enemy, Antipater. Eumenes may have thought that conflict with Antipater for the Perdiccan government was inevitable in any case, p.102.

- Plut. Eum., 4.3.

- Anson 2015, pp. 101, 104. Anson believes Eumenes had kept in contact and advised Cleopatra after Perdiccas married Nicaea. It is known that Eumenes and Cleopatra were childhood friends.

- Anson 2015, p. 103. Perdiccas' marriage to Cleopatra would give him a claim to the Macedonian throne.

- Anson 2015, p. 103.

- Anson 2015, pp. 105-106. Perdiccas had planned for it to travel to Macedon and further his claim to the throne, the Perdiccan government also believed Ptolemy had been in contact with Antipater and Craterus.

- Anson 2015, pp. 106-107. He probably received the command due to his loyalty to Perdiccas, skill in battle, and victories in Cappadocia and Armenia. Eumenes' satrapy was also expanded to include Antigonus' old provinces.

- ^ Heckel 2006, p. 121.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 84. Eumenes, again, served as subordinate Perdiccas and was to cooperate with Neoptolemus and Alcetas. His specific orders were to prevent Craterus and Antipater from crossing into Asia Minor; he failed in this.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 111.

- ^ Waterfield 2011, p. 58.

- Anson 2015, p. 112.

- Anson 2015, p. 114-115; Waterfield 2011, p. 58; Heckel 2006, p. 121. Neoptolemus disliked Eumenes because of his campaign in Armenia, while Alcetas had been distanced from his brother Perdiccas and saw his advice (marrying Nicaea) tossed out in favour of Eumenes' plan. Additionally, Eumenes was a Greek, a foreigner, not a Macedonian aristocrat like them, and this made them disrespect him. Alcetas also feared battle with Craterus would make their armies defect to the popular general.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 117.

- Plut. Eum., 5.4, 5.5.

- Plut. Eum., 5.3, 5.4. Eumenes' infantry were defeated, but he won the battle with his cavalry, capturing Neoptolemus' baggage and putting his army to rout.

- ^ Waterfield 2011, p. 59.

- Plut. Eum., 7.1.

- Anson 2015, pp. 109, 119. The battle took place 10 days after Neoptolemus' defection.

- Anson 2015, p. 119.

- Plut. Eum., 6.5-7.

- Anson 2015, p. 120. Some traditions say Craterus was not killed in the battle, but died of his wounds after it.

- Anson 2015, p. 121.

- Waterfield 2011, pp. 59–60.

- Romm 2011, p. 196.

- Plut. Eum., 8.1.

- Nep., 4.3.

- Anson 2015, p. 122. The chronology of the Diadochi Wars are contested among scholars, with three accepted chronologies: Low, High, and a mix of both. Anson argues extensively (pp.129-131) for 320 (the 'Low' dating) as the year of Perdiccas' murder.

- Anson 2015, p. 125. The reason for this condemnation, beyond the fact that Eumenes had supported the now deposed Perdiccas, was because of his killing of Craterus and Neoptolemus, which infuriated the assembled troops; Plut. Eum., 8.2.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 65.

- Diod., 18.39.6.

- Anson 2015, p. 127.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 67.

- ^ Waterfield 2011, p. 70.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 143.

- Plut. Eum., 8.6.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 132.

- Philip III and Alexander IV had accompanied Perdiccas as he moved into Egypt. With Perdiccas' death, the two kings passed into the hands of Antipater and Antigonus. Antipater became regent; growing suspicions between the two led Antipater to take the two kings to Macedonia.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 133.

- Plut. Eum., 8.3.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 135.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 69.

- Waterfield 2011, pp. 70, 71.

- Anson 2015, p. 135; Plut. Eum., 8.4.

- Anson 2015, pp. 135–136.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 89.

- ^ Plut. Eum., 8.4.

- Anson 2015, p. 139; Romm 2011, pp. 209, 353, points out that Eumenes, in his communications to the other Perdiccans (in which he had no reason to lie) "sought a restoration of the Babylon accords, the only legitimate plan for the organization of the empire, rather than a more ambitious goal".

- Anson 2015, pp. 140-141. A united Perdiccan offensive would have outnumbered Antigonus' army greatly in both infantry and especially in cavalry.

- Diod., 18.40.1-4.

- Plut. Eum., 8.4. Another translation of Eumenes' words (according to Plutarch) is: "This bears out the saying, 'Of perdition no account is made'".

- Anson 2015, p. 143; Waterfield 2011, p. 72. Eumenes reliance on cavalry meant the defection was very effective in crippling his army.

- Diod., 18.40.5-8.

- Billows 1990, p. 76, however; Anson 2015, p. 144 disbelieves it, arguing that Eumenes' cavalry superiority before the battle means he would have easily verified whether Antigonus had actually received reinforcements or not.

- Anson 2015, p. 144-145.

- Anson 2015, p. 145. Eumenes' campaigning there in 322/321 had pacified the area, but also probably meant he had contacts in there on whom he could rely.

- Diod., 18.41.1.

- Nep., 5.2.

- Anson 2015, p. 145 notes it is unclear how Eumenes' army performed this action, given Antigonus now had the advantage in cavalry and would thus have been able to easily scout his movements; Plut. Eum., 9.2.

- Plut. Eum., 9.2.

- ^ Plut. Eum., 9.3.

- Anson 2015, p. 145. Having lost their baggage in the Battle of Orkynia, Eumenes' troops would obviously be very eager to plunder the baggage of their enemies.

- Poly., 8.5.

- Anson 2015, p. 145.

- Plut. Eum., 9.6. Plutarch writes that Antigonus said: "Nay, my good men, did not let go out of regard for you, but because he was afraid to put such fetters on himself in his flight".

- Anson 2015, p. 146.

- ^ Waterfield 2011, p. 72.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 18.

- Anson 2015, p. 146. Anson believes this was done because Eumenes could not escape from Antigonus otherwise. Fewer men also alleviated supply demands, and Eumenes no doubt expected Antigonus to besiege him at Nora. Note; Nep., 5.3 who writes that Eumenes had 700 men, not 600.

- Plut. Eum., 10.1 agrees with the 700 figure.

- Diod., 18.41.2-3.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 147.

- ^ Plut. Eum., 10.2.

- Anson 2015, p. 147; Plut. Eum., 10.3. Plutarch also reports that Antigonus' soldiers crowded around to get a look at Eumenes, who had become well-known for his victory over Craterus.

- Diod., 18.41.6-7.

- Diod., 18.41.7. That Eumenes and Antigonus accepted that regent Antipater had the final say in this case suggests they were still deferring to the Macedonian royalty (the joint kings Philip III and Alexander IV were with Antipater in Macedonia at this point).

- Anson 2015, pp. 148, 150.

- Plut. Eum., 11.1-2. Plutarch provides a report of Eumenes' appearance; "He had a pleasant face, not like that of a war-worn veteran, but delicate and youthful, and all his body had ... artistic proportions ... and though he was not a powerful speaker, still he was insinuating and persuasive, as one may gather from his letters".

- Anson 2015, p. 149.

- Plut. Eum., 11.4-5.

- Anson 2015, p. 149; Diod., 18.42.1.

- This might have been because Antipater was dead before Hieronymus arrived in Macedonia; both events are dated to the late summer of 319.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 73.

- Diod., 18.48.4.

- Anson 2015, pp. 151-152. Antigonus' desire for Eumenes as a subordinate was for multiple reasons, their old friendship, Eumenes' skill as a commander, and that much of Antigonus' army were former Perdiccans who knew Eumenes.

- Anson 2015, pp. 152–153; Diod., 18.53.5.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 74.

- Anson 2015, pp. 152-154 discusses this at length. In essence: Eumenes could not have known that Antipater's death would cause another war, Diodorus does not mention a changed oath (and he is more generally more reliable than Plutarch/Nepos), and the evidence suggests he served Antigonus for some time before accepting Polyperchon's offer.

- See the following for a full discussion: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Siege-of-Nora%3A-A-Source-Conflict-Anson/8b76c278a8ee807c6b457e14cd05891dc9a7ff02

- If this occurred, swearing an oath to an infant (Alexander IV of Macedon) and a developmentally disabled man (Philip III Arrhidaeus), would have essentially gave Eumenes free rein to act in whatever manner he saw as in the best interest of the Argead Dynasty and, therefore, himself.

- Anson 2015, pp. 51–53, 159.

- Anson 2015, p. 155.

- Anson 2015, p. 159. Cleopatra of Macedon's marriages were probably coordinated by Olympias with Eumenes' help. Olympias, here, "probably asked whether she could trust Polyperchon, Antipater's chosen successor," and Eumenes, having campaigned with the man under Alexander, could answer accurately.

- ^ Waterfield 2011, p. 75.

- Anson 2015, p. 160.

- Bosworth 2005, pp. 19, 52, 99.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 162.

- Anson 2015, p. 162. Note; Diod., 18.58.2-4, where Olympias offers to help Eumenes by swaying commanders in the east to his side.

- Green 1990, p. 18.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 163.

- Diod., 18.59.1-3. That the Silver Shields listened to Polyperchon is because he had campaigned with them in the east, and was in charge of their repatriation under Craterus; his name carried weight. The joint kings also very much did.

- Plut. Eum., 13.2. Eumenes' status as a Greek foreigner probably exacerbated the existing disobedience of the Silver Shields, who were only really loyal to Alexander himself.

- Diod., 18.60.1-60.3.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 166.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 93.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 94.

- Anson 2015, p. 168.

- Nep., 7.3.

- Anson 2015, p. 164.

- Diod., 18.61.4-5.

- Anson 2015, p. 165; Waterfield 2011, p. 93.

- Diod., 18.62.1-2.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 101.

- Diod., 18.62.5-7; "since he was a foreigner, and would never dare to advance his own interests" Eumenes appeared more trustworthy than Antigonus.

- Anson 2015, p. 170.

- Anson 2015, p. 171; Diod., 18.63.3-5.

- Diod., 18.63.6.

- Anson 2015, p. 171.

- Poly., 4.6, 4.9.

- Waterfield 2011, pp. 83, 94.

- Anson 2015, pp. 172–175; Green 1990, p. 20.

- Diod., 18.73.1-2.

- Bosworth 2005, pp. 113-114 believes Amphimachus, as reported by Arrian, was the brother of Philip III Arrhidaeus through a previous marriage of the king's mother. Thus, Amphimachus' joining Eumenes lent him further royalist legitimacy; Diod., 18.39.6, 19.27.4.

- Anson 2015, p. 173; Diod., 19.12.1-2.

- Anson 2015, pp. 173, 176; Bosworth 2005, p. 109. Peithon and Seleucus had plans for the Upper Satrapies, and Eumenes, whose power base went with him, was seen as a threat; Antigonus, meanwhile, was based in Asia Minor and thus appeared less inherently dangerous.

- Diod., 19.12.2.

- Anson 2015, p. 174; Diod., 17.110.3-8.

- Diod., 19.13.6-7.

- Anson 2015, p. 175.

- Anson 2015, pp. 175–176; Diod., 19.13.7.

- Diod., 19.12.3-5, 19.13.1-4. They refused to battle him, however, since their armies were much smaller.

- Anson 2015, p. 178.

- Billows 1990, p. 90; Anson 2015, pp. 175, 178; Diod., 19.14.5-8.

- Anson 2015, p. 179; Waterfield 2011, p. 96. Eumenes' foreign heritage probably aided Peucestas' claims for overall command.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 114; Diod., 19.15.3.

- Nep., 7.2, 7.3.

- Anson 2015, p. 179. Eumenes still held authority as the general of the kings who could command the treasuries, however; Nep., 7.3 "everything was done by direction alone".

- Anson 2015, p. 180; Romm 2011, p. 280; Bosworth 2005, p. 114. Whether it actually constituted a bribe is debated, since the money, 200 talents, could also have been intended for maintaining Eudamus' elephants, as argued by Bosworth.

- Diod., 19.17.3.

- Diod., 19.17.3-7.

- Anson 2015, p. 181.

- Romm 2011, p. 283.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 182.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 116.

- Anson 2015, p. 181. Peucestas agreed because of his fear of Antigonus, and because he believed more troops would make his chances of attaining sole command more likely.

- Diod., 19.17.5-7.

- Diod., 19.18.3. It was 3,400 men.

- Diod., 19.18.3.

- Anson 2015, pp. 182–183.

- Anson 2015, p. 183; Plut. Eum., 14.1-2. The majority of these men were light-armed foragers who had no chance against Eumenes' soldiers. The Macedonians who crossed put up a brief resistance but were overwhelmed.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 97; Diod., 19.18.3-7.

- Billows 1990, pp. 91, 92.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 117, who calls this "one of the great disasters of the post-Alexander period, comparable to the defeat Eumenes himself had suffered ".

- Bosworth 2005, pp. 117–118; Diod., 19.18.5-19.2.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 97.

- Anson 2015, p. 185; Waterfield 2011, p. 97.

- Billows 1990, p. 93. Eumenes could cut supply lines, retake Syria as Seleucus was unable to stop him, and then pose a significant danger by threatening to link up again with Polyperchon.

- Romm 2011, p. 283; Bosworth 2005, p. 120. Romm believes jealousy over the victory at the Coprates, which Eumenes apparently engineered alone, may have contributed to this refusal. Also, Antigonus' move to Ecbatana threatened the satraps' lands.

- Anson 2015, p. 185.

- Anson 2015, p. 185; Bosworth 2005, p. 121.

- Romm 2011, pp. 285, 286; Diod., 19.22.2, 19.23.1.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 98; Plut. Eum., 13.4.

- Romm 2011, p. 286 hypothesizes this was because doing so would lead to an open split among the army.

- Who may have been Orontes II

- Anson 2015, p. 186; Bosworth 2005, p. 122.

- Diod., 19.23.2-3.

- Romm 2011, p. 286; Anson 2015, pp. 186, 188; Bosworth 2005, p. 122. The letter was also "based on facts known to the army" of the war in Macedon, namely Olympias' return and initial success, and this contributed to their belief.

- Billows 1990, p. 93; Anson 2015, p. 188.

- Anson 2015, p. 188; Bosworth 2005, p. 122-123; Diod., 19.23.4, 19.24.1. Whether the charges against Sibyrtius had any merit (Eumenes accused him of colluding with Antigonus, with whom he was old friends) is not known. Eumenes intended to intimidate the upper satraps and consolidate his own control, and in this he was successful. Bosworth contends that Eumenes wanted to replace Sibyrtius with a more loyal satrap, Tlepolemus.

- Anson 2015, p. 188; Bosworth 2005, p. 123; Plut. Eum., 13.6.

- Anson 2015, pp. 188–189; Bosworth 2005, p. 98; Billows 1990, p. 94.

- Anson 2015, p. 189; Bosworth 2005, p. 126. Bosworth believes Eumenes utilized his sickness, and the rumour that Peucestas had poisoned him, to imitate Alexander the Great and grow his own power. Anson believes Eumenes was just ill, since surrendering authority to his rivals would go against Eumenes' multiple efforts to consolidate his own control.

- Anson 2015, p. 189, who points out that these coalition soldiers had only seen Eumenes and Antigonus clash once at the Coprates, where Eumenes was victorious.

- Anson 2015, p. 189.

- Diod., 19.24.5-6.

- Plut. Eum., 15.1-2.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 190.

- Anson 2015, p. 194; Billows 1990, pp. 95–98; Diod., 19.26-32.2. Northwest of Persepolis.

- Anson 2015, p. 190; Bosworth 2005, pp. 127, 129; Waterfield 2011, p. 98.

- Anson 2015, p. 190; Diod., 19.25.4, where Eumenes compares Antigonus to the father of a bride who declaws and defangs a lion to kill it, having enticed it to do so by offering his daughter as a wife.

- Anson 2015, p. 190. Eumenes "knew that Antigonus would be seeking an unplundered area, rich in provisions, and easily defended for his winter quarters. Gabiene was the only such area in the vicinity, and it was but three days distant".

- Diod., 19.26.1-2.

- Anson 2015, p. 191; Diod., 19.26.3-4.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 130.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 191.

- Diod., 19.26.7-9. Eumenes saw the cavalry appear at the top of a ridge, and fearing the entire enemy had appeared, prepared his army for battle. Antigonus' successful deception allowed the rest of his army to catch up.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 98; Romm 2011, p. 287.

- Anson 2015, pp. 191–192; Diod., 19.28.1, 3-4, 29.1; Bosworth 2005, p. 130.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 132; Diod., 19.28.2. Elephants also screened the right cavalry.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 133.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 137.

- Anson 2015, pp. 193; Bosworth 2005, p. 139. Anson does not believe the reports, followed by; Billows 1990, p. 95, that Peithon acted against Antigonus' orders, citing Peithon's continued command under Antigonus and the initial tactical success of his maneuver; Diod., 19.30.1-4, 19.29.1.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 193.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 140; Waterfield 2011, p. 99.

- Diod., 19.31.3.

- Anson 2015, p. 195. It is generally agreed that Antigonus lost this battle, since he had vastly more losses and lost the original objective of Gabiene.

- Diod., 19.30.9-31.5, 19.37.1 gives Antigonus' losses as 3700 infantry and 54 cavalry dead, with 4000 wounded. Eumenes is said to have lost 540 men and a few cavalry, with 900 wounded.

- Anson 2015, p. 195; Bosworth 2005, p. 141.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 141; Diod., 32.1-2. So Bosworth, in so doing Antigonus "in effect admitted defeat".

- Anson 2015, p. 195. He could have pursued Antigonus, but his men were exhausted and lacked supplies.

- Anson 2015, p. 195 believes Antigonus' charge probably prevented the defeat from being decisive.

- Anson 2015, p. 195; Nep., 8.3; Bosworth 2005, p. 142.

- Diod., 19.37.5-6.

- Anson 2015, p. 196; Diod., 19.37.2-6.

- Bosworth 2005, pp. 143–144; Waterfield 2011, p. 100; & Poly., 4.6,11, 8.4.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 142.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 100.

- Anson 2015, p. 196; Bosworth 2005, p. 145.

- Plut. Eum., 15.8.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 197.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 145; Waterfield 2011, p. 100.

- Anson 2015, p. 197; Roisman 2012, pp. 223–224.

- Bosworth 2005, pp. 146–147; Anson 2015, pp. 197–198.

- Anson 2015, p. 198; Plut. Eum., 16.1-3, 6. There are multiple possible reasons why. Most were loyal to Eumenes only nominally, and out of fear of Antigonus. A victorious Eumenes with the remnants of Antigonus' army would also vastly eclipse them in power.

- Anson 2015, pp. 198–199; Plut. Eum., 16.3. Plutarch has Eudamus and one other warn Eumenes because of the money he owed them. Anson finds this improbable as Eudamus was a hated enemy of Antigonus and needed no other motivation to help Eumenes.

- Anson 2015, p. 199.

- Anson 2015, p. 199; Plut. Eum., 16.4-6..

- Diod., 19.39.6.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 200.

- Anson 2015, p. 200; Diod., 19.40.2, 19.42.7; Bosworth 2005, p. 151.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 151; Romm 2011, p. 297.

- ^ Waterfield 2011, p. 101.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 151.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 152.

- ^ Bosworth 2005, p. 153.

- Anson 2015, p. 201; Bosworth 2005, p. 154; Waterfield 2011, p. 101; Roisman 2012, p. 227. The reason for Peucestas' retreat, which "decided the battle" is debated. Cowardice or betrayal are the two proposed reasons, of which "an act of betrayal, nicely judged and timed" has, generally, more scholarly consensus. Note; Roisman 2012, (passim) who believes the negative depiction of Peucestas in ancient sources comes from the bias of the historian Hieronymus of Cardia.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 154.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 154; Diod., 19.42.5.

- Diod., 19.42.7.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 202.

- Anson 2015, p. 201; Diod., 19.43.1.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 155.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 156; Waterfield 2011, p. 101; Diod., 19.43.2. The phrase was apparently meant to mirror Alexander the Great, who is said to have declared the same thing at the Battle of Gaugamela against Darius III.

- Bosworth 2005, pp. 156–157.

- Anson 2015, p. 201.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 157.

- Diod., 19.43.2-3.

- Diod., 19.42.1-3; Plut. Eum., 16.5-6; Poly., 4.6.13; Billows 1990, pp. 100–102.

- Anson 2015, p. 199; Plut. Eum., 16.4-6.; TroncosoAnson 2013, p. 105.

- Anson 2015, p. 202; Bosworth 2005, p. 157.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 101; Bosworth 2005, p. 157.

- TroncosoAnson 2013, p. 105.

- Anson 2015, p. 202; Bosworth 2005.

- Diod., 19.42.4, 43.8; Plut. Eum., 16.4-17, 1; Poly., 4.6.13; Billows 1990, pp. 102–103.

- Anson 2015, pp. 199, 203. Anson calls Eumenes' declaration to continue the battle the "fatal miscalculation" which cost him his life.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 203.

- Plut. Eum., 17.3-5. A different translation has been used here for readability.

- Plut. Eum., 18.4; Nep., 11.3-5.

- Diod., 19.43.8-44.3; Plut. Eum., 17.1-19.1; Billows 1990, p. 104; Anson 2015, p. 204, "Antigonus' own Macedonian troops wanted the death of the man who had caused them so much suffering".

- Diod., 19.43.8-44.3; Plut. Eum., 17.1-19.1; Billows 1990, p. 104.

- Anson 2015, p. 204.

- Diod., 18.60.1-3.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 205.

- See citation 4, at the end of the first paragraph of this article, for a short discussion on Eumenes' motivations.

- ^ Waterfield 2011, p. 102.

- Billows 1990, p. 316, 318. Billows holds that Antigonus and Eumenes were both "first-rate generals".

- Bosworth 2005, pp. 9, 18.

- Anson 2015, pp. 204, 261.

- Bosworth 2005, p. 126.

- Chisholm 1911; Anson 2015, pp. 181, 205, 261.

- Waterfield 2011, p. 98; Romm 2011, p. 280; Bosworth 2005, p. 167-168, 'The Campaign in Iran' passim.

- Anson 2015, viii.

- Bosworth 2005, v. If Eumenes was victorious, the ensuing Hellenistic Period may have been different in terms of structure, as the Argeads could possibly have retained a position of authority.

- Green 1990, p. 20.

- Romm 2011, pp. 303, 304.

- Anson 2015, p. 261.

Bibliography

Ancient sources

- Plutarch (1919) . "Life of Eumenes". Parallel Lives. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 8. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. OCLC 40115288 – via LacusCurtius.

- Diodorus (1947) . "Books XVIII, XIX". Library of History. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 9. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte – via LacusCurtius.

- Cornelius Nepos (1929). Excellentium imperatorum vitae (De Viris Illustribus). Translated by Rolfe, J.C. – via Attalus.org.

- Polyaenus (1793). "Book 4, 6 & 8". Strategems. Translated by Shepherd, R. – via Attalus.org.

- Photius. "92. [Arrian, Continuation]". Bibliotheca or Myrobiblion – via tertullian.org.

- Justinus (1853). "Book 13-14". Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories. Translated by Watson, J.S. – via Attalus.org.

Modern sources

- Anson, Edward M. (2015). Eumenes of Cardia: a Greek among Macedonians (2nd Edition). Vol. 383. ISBN 9004297154.

- Billows, Richard A. (1990). Antigonos the One-eyed and the creation of the Hellenistic state. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520208803.

- Boiy, Tom (2010). "ROYAL AND SATRAPAL ARMIES IN BABYLONIA DURING THE SECOND DIADOCH WAR. THE "CHRONICLE OF THE SUCCESSORS" ON THE EVENTS DURING THE SEVENTH YEAR OF PHILIP ARRHIDAEUS (=317/316 BC)". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 130 (3): 1–13. JSTOR 41722527 – via JSTOR.

- Bosworth, A.B. (2005). The Legacy of Alexander: Politics, Warfare, and Propaganda under the Successors. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198153061.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Eumenes (general)" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 889.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520083493.

- Heckel, Waldemar (2006). Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405112109.

- Roisman, Joseph (2012). Alexander's Veterans and the Early Wars of the Successors. University of Texas Press, Austin. ISBN 9780292735965.

- Romm, James (2011). Ghost on the Throne. Alfred A. Knoff: Random House. ISBN 9780307701503.

- Waterfield, Robin (2011). Dividing the Spoils. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195395235.

- Troncoso, Victor Alonso; Anson, Edward, eds. (2013). "The Battle of Gabene: Eumenes' Inescapable Doom?". AFTER ALEXANDER: The Time of the Diadochi (323-281 BC). Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781782970637.

External links

- The Life of Eumenes by Plutarch Archived 2005-12-30 at the Wayback Machine

- The Historical Library by Diodorus - books XVIII and XIX

- The Life of Eumenes by Cornelius Nepos

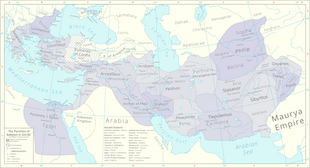

| The division of Alexander's empire | |

|---|---|

|

| Works of Plutarch | |

|---|---|

| Works | |

| Lives |

|

| Translators and editors | |

| |

- 4th-century BC Greek people

- Ancient Thracian Greeks

- Ancient Greek generals

- Generals of Alexander the Great

- Generals of Philip II of Macedon

- Trierarchs of Nearchus' fleet

- Satraps of the Alexandrian Empire

- Macedonian royal secretaries

- 360s BC births

- 310s BC deaths

- Executed ancient Greek people

- Battles involving Phoenicia