| This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (June 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

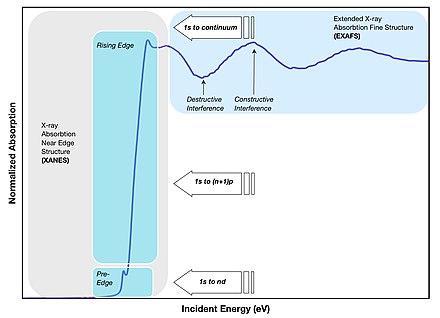

Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), along with X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES), is a subset of X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Like other absorption spectroscopies, XAS techniques follow Beer's law. The X-ray absorption coefficient of a material as a function of energy is obtained by directing X-rays of a narrow energy range at a sample, while recording the incident and transmitted x-ray intensity, as the incident x-ray energy is incremented.

When the incident x-ray energy matches the binding energy of an electron of an atom within the sample, the number of x-rays absorbed by the sample increases dramatically, causing a drop in the transmitted x-ray intensity. This results in an absorption edge. Every element has a set of unique absorption edges corresponding to different binding energies of its electrons, giving XAS element selectivity. XAS spectra are most often collected at synchrotrons because the high intensity of synchrotron X-ray sources allows the concentration of the absorbing element to reach as low as a few parts per million. Absorption would be undetectable if the source were too weak. Because X-rays are highly penetrating, XAS samples can be gases, solids or liquids.

Background

EXAFS spectra are displayed as plots of the absorption coefficient of a given material versus energy, typically in a 500 – 1000 eV range beginning before an absorption edge of an element in the sample. The x-ray absorption coefficient is usually normalized to unit step height. This is done by regressing a line to the region before and after the absorption edge, subtracting the pre-edge line from the entire data set and dividing by the absorption step height, which is determined by the difference between the pre-edge and post-edge lines at the value of E0 (on the absorption edge).

The normalized absorption spectra are often called XANES spectra. These spectra can be used to determine the average oxidation state of the element in the sample. The XANES spectra are also sensitive to the coordination environment of the absorbing atom in the sample. Finger printing methods have been used to match the XANES spectra of an unknown sample to those of known "standards". Linear combination fitting of several different standard spectra can give an estimate to the amount of each of the known standard spectra within an unknown sample.

The dominant physical process in x-ray absorption is one where the absorbed photon ejects a core photoelectron from the absorbing atom, leaving behind a core hole. The ejected photoelectron's energy will be equal to that of the absorbed photon minus the binding energy of the initial core state. The atom with the core hole is now excited and the ejected photoelectron interacts with electrons in the surrounding non-excited atoms.

If the ejected photoelectron is taken to have a wave-like nature and the surrounding atoms are described as point scatterers, it is possible to imagine the backscattered electron waves interfering with the forward-propagating waves. The resulting interference pattern shows up as a modulation of the measured absorption coefficient, thereby causing the oscillation in the EXAFS spectra. A simplified plane-wave single-scattering theory has been used for interpretation of EXAFS spectra for many years, although modern methods (like FEFF, GNXAS) have shown that curved-wave corrections and multiple-scattering effects can not be neglected. The photelectron scattering amplitude in the low energy range (5-200 eV) of the photoelectron kinetic energy become much larger so that multiple scattering events become dominant in the XANES (or NEXAFS) spectra.

The wavelength of the photoelectron is dependent on the energy and phase of the backscattered wave which exists at the central atom. The wavelength changes as a function of the energy of the incoming photon. The phase and amplitude of the backscattered wave are dependent on the type of atom doing the backscattering and the distance of the backscattering atom from the central atom. The dependence of the scattering on atomic species makes it possible to obtain information pertaining to the chemical coordination environment of the original absorbing (centrally excited) atom by analyzing these EXAFS data.

The effect of the backscattered photoelectron on the absorption spectra is described by the EXAFS equation, first demonstrated by Sayers, Stern, and Lytle. The oscillatory part of the dipole matrix element is given by , where the sum is over the sets of neighbors of the absorbing atom, is the number of atoms at distance , is the wavenumber and is proportional to energy, is the thermal vibration factor with being the mean square amplitude of the atom's relative displacements, is the mean free path of the photoelectron with momentum (this is related to coherence of the quantum state), and is an element dependent scattering factor.

The origin of the oscillations in the absorption cross section are due to the term which imposes the interference condition, leading to peaks in absorption when the wavelength of the photoelectron is equal to an integer fraction of (the round trip distance from the absorbing atom to the scattering atom). This is analogous to eigenstates of the particle in a box toy model. The factor inside the is an element dependent phase shift.

Experimental considerations

Since EXAFS requires a tunable x-ray source, data are frequently collected at synchrotrons, often at beamlines which are especially optimized for the purpose. The utility of a particular synchrotron to study a particular solid depends on the brightness of the x-ray flux at the absorption edges of the relevant elements.

Recent developments in the design and quality of crystal optics have allowed for some EXAFS measurements to take place in a lab setting, where the tunable x-ray source is achieved via a Rowland circle geometry. While experiments requiring high x-ray flux or specialized sample environments can still only be performed at synchrotron facilities, absorption edges in the 5 - 30 keV range are feasible for lab based EXAFS studies.

Applications

XAS is an interdisciplinary technique and its unique properties, as compared to x-ray diffraction, have been exploited for understanding the details of local structure in:

- glass, amorphous and liquid systems

- solid solutions

- doping and ionic implantation of materials for electronics

- local distortions of crystal lattices

- organometallic compounds

- metalloproteins

- metal clusters

- vibrational dynamics

- ions in solutions

- chemical speciation analysis

XAS provides complementary to diffraction information on peculiarities of local structural and thermal disorder in crystalline and multi-component materials.

The use of atomistic simulations such as molecular dynamics or the reverse Monte Carlo method can help in extracting more reliable and richer structural information.

Examples

EXAFS is, like XANES, a highly sensitive technique with elemental specificity. As such, EXAFS is an extremely useful way to determine the chemical state of practically important species which occur in very low abundance or concentration. Frequent use of EXAFS occurs in environmental chemistry, where scientists try to understand the propagation of pollutants through an ecosystem. EXAFS can be used along with accelerator mass spectrometry in forensic examinations, particularly in nuclear non-proliferation applications.

History

A very detailed, balanced and informative account about the history of EXAFS (originally called Kossel's structures) is given by R. Stumm von Bordwehr. A more modern and accurate account of the history of XAFS (EXAFS and XANES) is given by the leader of the group that developed the modern version of EXAFS in an award lecture by Edward A. Stern.

See also

- X-ray absorption spectroscopy

- X-ray absorption near edge structure

- Surface-extended X-ray absorption fine structure

References

- Glatzel, Pieter; Bergmann, Uwe (2005). "High resolution 1s core hole X-ray spectroscopy in 3d transition metal complexes—electronic and structural information". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 249 (1–2): 65–95. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.04.011.

- Sayers, Dale E.; Stern, Edward A.; Lytle, Farrel W. (1 October 1971). "New Technique for Investigating Noncrystalline Structures: Fourier Analysis of the Extended X-Ray—Absorption Fine Structure". Physical Review Letters. 27 (18). American Physical Society (APS): 1204–1207. Bibcode:1971PhRvL..27.1204S. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.27.1204. ISSN 0031-9007.

- Mortensen, Devon; Seidler, Gerald (2017). "Robust optic alignment in a tilt-free implementation of the Rowland circle spectrometer". Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena. 215: 8–15. doi:10.1016/j.elspec.2016.11.006.

- Jahrman, Evan; Holden, William; Ditter, Alexander; Mortensen, Devon; Seidler, Gerald; Fister, Timothy; Kozimor, Stosh; Piper, Louis; Rana, Jatinkumar; Hyatt, Neil; Stennett, Martin (2019). "An improved laboratory-based x-ray absorption fine structure and x-ray emission spectrometer for analytical applications in materials chemistry research" (PDF). Review of Scientific Instruments. 90: 024106. doi:10.1063/1.5049383.

- Bordwehr, R. Stumm von (1989). "A History of X-ray absorption fine structure". Annales de Physique. 14 (4): 377–465. Bibcode:1989AnPh...14..377S. doi:10.1051/anphys:01989001404037700. ISSN 0003-4169.

- Stern, Edward A. (2001-03-01). "Musings about the development of XAFS". Journal of Synchrotron Radiation. 8 (2): 49–54. doi:10.1107/S0909049500014138. ISSN 0909-0495. PMID 11512825.

Bibliography

Books

- Calvin, Scott. (2013-05-20). XAFS for everyone. Furst, Kirin Emlet. Boca Raton. ISBN 9781439878637. OCLC 711041662.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bunker, Grant, 1954- (2010). Introduction to XAFS : a practical guide to X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511809194. OCLC 646816275.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Teo, Boon K. (1986). EXAFS: Basic Principles and Data Analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 9783642500312. OCLC 851822691.

- X-ray absorption : principles, applications, techniques of EXAFS, SEXAFS, and XANES. Koningsberger, D. C., Prins, Roelof. New York: Wiley. 1988. ISBN 0471875473. OCLC 14904784.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Book chapters

- Kelly, S. D.; Hesterberg, D.; Ravel, B.; Ulery, April L.; Richard Drees, L. (2008). "Analysis of Soils and Minerals Using X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy". Methods of Soil Analysis Part 5. Soil Science Society of America. doi:10.2136/sssabookser5.5.c14. ISBN 9780891188575. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-16. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

Papers

- Stern, Edward A. (1 February 2001). "Musings about the development of XAFS" (PDF). Journal of Synchrotron Radiation. 8 (2). International Union of Crystallography (IUCr): 49–54. doi:10.1107/s0909049500014138. ISSN 0909-0495. PMID 11512825.

- Rehr, J. J.; Albers, R. C. (1 June 2000). "Theoretical approaches to x-ray absorption fine structure". Reviews of Modern Physics. 72 (3). American Physical Society (APS): 621–654. Bibcode:2000RvMP...72..621R. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.72.621. ISSN 0034-6861.

- Filipponi, Adriano; Di Cicco, Andrea; Natoli, Calogero Renzo (1 November 1995). "X-ray-absorption spectroscopy and n-body distribution functions in condensed matter. I. Theory". Physical Review B. 52 (21). American Physical Society (APS): 15122–15134. Bibcode:1995PhRvB..5215122F. doi:10.1103/physrevb.52.15122. ISSN 0163-1829. PMID 9980866.

- de Groot, Frank (2001). "High-Resolution X-ray Emission and X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy". Chemical Reviews. 101 (6). American Chemical Society (ACS): 1779–1808. doi:10.1021/cr9900681. hdl:1874/386323. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 11709999. S2CID 44020569.

- F.W. Lytle, "The EXAFS family tree: a personal history of the development of extended X-ray absorption fine structure",

- Sayers, Dale E.; Stern, Edward A.; Lytle, Farrel W. (1 October 1971). "New Technique for Investigating Noncrystalline Structures: Fourier Analysis of the Extended X-Ray—Absorption Fine Structure". Physical Review Letters. 27 (18). American Physical Society (APS): 1204–1207. Bibcode:1971PhRvL..27.1204S. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.27.1204. ISSN 0031-9007.

- A. Kodre, I. Arčon, Proceedings of 36th International Conference on Microelectronics, Devices and Materials, MIDEM, Postojna, Slovenia, October 28–20, (2000), p. 191-196

External links

- International X-ray Absorption Society

- FEFF Project, University of Washington, Seattle Archived 2022-01-21 at the Wayback Machine

- GNXAS project and XAS laboratory, Università di Camerino

- EXAFS Spectroscopy Laboratory (Riga, Latvia)

- Community web site for XAFS

| Spectroscopy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibrational (IR) | |||||||

| UV–Vis–NIR "Optical" | |||||||

| X-ray and Gamma ray | |||||||

| Electron | |||||||

| Nucleon | |||||||

| Radiowave | |||||||

| Others |

| ||||||

, where the sum is over the

, where the sum is over the  sets of neighbors of the absorbing atom,

sets of neighbors of the absorbing atom,  is the number of atoms at distance

is the number of atoms at distance  ,

,  is the

is the  is the thermal vibration factor with

is the thermal vibration factor with  being the mean square amplitude of the atom's relative displacements,

being the mean square amplitude of the atom's relative displacements,  is the mean free path of the photoelectron with momentum

is the mean free path of the photoelectron with momentum  is an element dependent scattering factor.

is an element dependent scattering factor.

term which imposes the

term which imposes the  (the round trip distance from the absorbing atom to the scattering atom). This is analogous to eigenstates of the

(the round trip distance from the absorbing atom to the scattering atom). This is analogous to eigenstates of the  factor inside the

factor inside the