FNA mapping is an application of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) to the testis for the diagnosis of male infertility. FNA cytology has been used to examine pathological human tissue from various organs for over 100 years. As an alternative to open testicular biopsy for the last 40 years, FNA mapping has helped to characterize states of human male infertility due to defective spermatogenesis. Although recognized as a reliable, and informative technique, testis FNA has not been widely used in U.S. to evaluate male infertility. Recently, however, testicular FNA has gained popularity as both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool for the management of clinical male infertility for several reasons:

- The testis is an ideal organ for evaluation by FNA because of its uniform cellularity and easy accessibility.

- The trend toward minimally invasive procedures and cost-containment views FNA favorably compared to surgical testis biopsy.

- The realization that the specific histologic abnormality observed on testis biopsy has no definite correlation to either the etiology of infertility or to the ability to find sperm for assisted reproduction.

- Assisted reproduction has undergone dramatic advances such that testis sperm are routinely used for biological pregnancies, thus fueling the development of novel FNA techniques to both locate and procure sperm.

For these reasons, there has been a resurgence of FNA as an important, minimally invasive tool for the evaluation and management of male infertility.

Changes to infertility medicine

Advances in assisted reproductive technology (ART) have revolutionized the ability to help men with even the severest forms of male infertility to become fathers. This field began in earnest in 1978 when the first successful in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle was performed. This technique involves controlled ovarian stimulation followed by egg retrieval, in vitro fertilization, and embryo transfer to the uterus. In the United States, the number of babies born to infertile couples with IVF has risen logarithmically from 260 babies in 1985 to almost 50,000 in 2003. Another significant advance in ART was the development of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in 1992. Performed in conjunction with IVF, ICSI involves the injection of a single, viable sperm directly into the egg cytoplasm in vitro to facilitate fertilization in cases of low sperm numbers. ICSI has decreased the numerical sperm requirement for egg fertilization with IVF from hundreds of thousands of sperm for each egg to a single sperm. In addition, ICSI allows sperm with limited intrinsic fertilizing capacity, including "immature" sperm obtained from the reproductive tract of men with no sperm in the ejaculate to reliably fertilize eggs. Indeed, ICSI has become so popular that U.S. clinics have routinely used it in more than 56% of their IVF cases.

The success of ICSI has also encouraged reproductive clinicians to look beyond the ejaculate and into the male reproductive tract to find sperm. Currently, sources of sperm routinely used for ICSI include sperm from the vas deferens, epididymis, and testicle. As ART has evolved, so too have novel FNA techniques to help diagnose and treat severe male infertility. An example of this is use of testicular FNA "mapping" to systemically assess and localize sperm for ART in men with azoospermia (no sperm count) and with testis failure characterized by "patchy" or "focal" spermatogenesis. Indeed, this combination of techniques has allowed men with even the severest forms of infertility, including men who are azoospermic after chemotherapy for cancer, to become fathers.

Accuracy

From a contemporary search of the English literature, it is apparent that the diagnostic testis biopsy has been used to study the pathological basis of male infertility for 60 years. The surgically obtained testis biopsy accurately describes testis architecture, is the best technique to detect in situ neoplasia or cancer, and allows for the overall assessment of the interstitium (Leydig cell number and hypertrophy). Levin described a qualitative method of assessing testis histologic patterns that is commonly used clinically to assess testis pathology in male infertility. Recognized patterns include: normal spermatogenesis, hypoplasia or hypospermatogenesis, complete or early maturation arrest, Sertoli cell-only or germ cell aplasia, incomplete or late maturation arrest, and sclerosis. Johnsen proposed a more quantitative analysis of testis cellular architecture based on the concept that testis damage causes a successive disappearance of the most mature germ cell type. The Johnsen scoring system involves a quantitative assessment of individual germ cell types that is very detailed and relatively laborious for routine clinical use.

Regardless of methodology, the analysis of testis biopsy histology lacks clinical value in cases of infertility because there is no clear correlation between histologic patterns or Johnsen score and the underlying etiology of infertility. That is to say, the clinical utility of understanding the histology pattern is low, because biopsy patterns do not correlate well with specific and correctable diseases. In addition, the interobserver variability in testis biopsy readings for infertility is significant. This was aptly demonstrated in a study by Cooperberg et al. in which the histology readings from two independent pathological reviews were prospectively compared with 113 testis biopsies undertaken for infertility. Importantly, in 28% of cases preparation artifact or insufficient biopsy size rendered the sample suboptimal for interpretation. In addition, in 46% of cases, the two reviews disagreed, and this discordance resulted in significant changes in clinical care in 27% of cases. The most common error in pathological review was the under-appreciation of mixed histological patterns that are common and characteristic of infertile men with no sperm counts. Thus, although commonly used, the classical testis biopsy has little or no correlation with specific diseases, is associated with significant variability in interpretation, and can miss mixed patterns of spermatogenesis that may qualify infertile men for assisted reproduction.

FNA cytology vs testis biopsy

In many countries, testicular FNA cytology is preferable to surgical testis biopsy for the evaluation of male infertility. In addition to accurately demonstrating the presence or absence of mature sperm with tails, FNA provides tubular cells for cytologic analysis, also informative for the diagnosis of infertility. Unlike testis biopsy histology, however, FNA cytology has not been rigorously evaluated for the ability to distinguish in situ neoplasia and testis cancer. Despite this caveat, the correlation of FNA cytology to testis biopsy histology is very high (84–97%) in comparative studies comprising almost 400 patients (Table 1).

| Study | # Patients | % Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Persson, 1971 | 42 | 86% |

| Gottschalk-Sabag, 1993 | 47 | 87% |

| Mallidis, 1994 | 46 | 94% |

| Craft, 1997 | 19 | 84% |

| Odabas, 1997 | 24 | 90% |

| Mahajan, 1999 | 60 | 97% |

| Rammou-Kinia, 1999 | 30 | 87% |

| Meng, 2000 | 87 | 94% |

| Qublan, 2002 | 34 | 96% |

| Aridogan, 2003 | 40 | 90% |

| Mehrotra, 2007 | 58 | 94% |

Similar to the issue with biopsy histology, although several excellent descriptions of testis seminiferous epithelium cytology have been reported, no individual classification method has been uniformly adopted by cytologists as a standard approach. Papic et al. quantified each cell type and calculated various cell indices and ratios and found that cytologic smears correlated well with histologic diagnoses. Verma et al. also determined differential cell counts in patients with normal spermatogenesis; however, the reported ratios differed dramatically from those of Papic. Batra et al. have also published a cytologic schema in which the spermatic index, Sertoli cell index, and sperm-Sertoli cell indices are categorized into various histologic groups. Using this system, they reported that differences in cell counts and indices could predict histologic categories. Among the different classification systems for testis FNA, those that attempt to correlate cytologic findings with biopsy histology hold the most promise to replace histology.

With the goal of replacing the more invasive biopsy histology with FNA cytology, a simple, working classification schema for testis FNA cytology has been proposed that is based on pattern recognition. The identified patterns represent histological diagnoses but are based on relative numbers of three easily identified germ cell types on cytologic assessment: primary spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa. The various germ and Sertoli cells are not precisely counted but are loosely quantified by assessing the relative number of cells present. In this way, a standard ratio of cell types for comparison to Sertoli cell density is created. The FNA patterns for hypospermatogenesis, Sertoli cell-only, early maturation arrest, and late maturation arrest show different ratios of these three cell types relative to normal spermatogenesis and are relatively easy to categorize in this way. In a review of 87 patients with paired FNA maps and biopsy, this cytologic classification was observed to be reproducible and accurate. Histologic categories determined by FNA patterns correlated well with open biopsy histology across all patterns in 94% of cases. FNA cytology was also able to completely describe mixed histologies in 12 of 14 cases. Thus, the determination of histology by FNA cytology pattern is accurate and suggests that the more invasive testis biopsy is unnecessary to diagnose states of infertility. Alternatively, it is possible that newer processing methods can be applied to testis FNA cytology specimens to concentrate and prepare seminiferous tubules for sectioning similar to classic histologic preparations. Either way, testis cytology is a viable alternative to histology in the evaluation of male infertility.

Newer concepts: FNA "mapping"

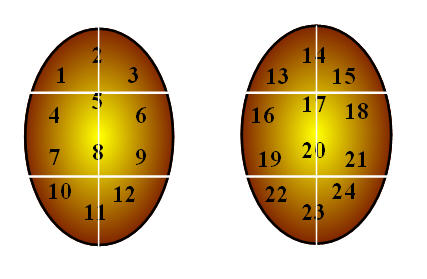

It has become clear to reproductive urologists who regularly perform testis sperm retrieval in azoospermic men for IVF-ICSI that spermatogenesis varies geographically within the testis. This underscores the limitation and inadequacy of a single, localized testis biopsy or a single FNA specimen to accurately reflect the biology of the entire organ. In fact, the current clinical challenges are: (1) to determine which infertile men with azoospermia harbor sperm for IVF-ICSI and (2) to precisely locate the areas of sperm production within atrophic, nonobstructed testes. This clinical need led to the development of testis FNA "mapping" in male infertility by a team of University of California San Francisco physicians led by Paul J. Turek (Figure 1).

In a pilot study of 16 men from 1997, testis FNA was used to "map" the organ for mature sperm. The concept for mapping testis for sperm was inspired by the work of Gottschalk-Sabag and colleagues and modeled after the approach to prostate biology in which multiple prostate biopsies are used to detect foci of prostate cancer. Similarly, FNA was applied systematically to detect the presence or absence of sperm in varied geographical areas of the testis. In this study, azoospermic men underwent simultaneous testis biopsies and site-matched FNA, and FNA was found to be more sensitive in detecting sperm, as several men had sperm found by FNA but not on biopsy. Additionally, in one-third of patients, localized areas of sperm were detected by FNA in areas distant from biopsy sites without sperm. These data confirmed intratesticular heterogeneity with respect to sperm distribution and suggested the potential of FNA to localize patches of active spermatogenesis in failing testes.

Testicular FNA mapping is performed using classic FNA technique. Under local anesthesia in the office, the testis and scrotal skin are fixed relative to each other with a gauze wrap. The "testicular wrap" is a convenient handle to manipulate the testis and also fixes the scrotal skin over the testis for the procedure. Aspiration sites are marked on the scrotal skin, 5 mm apart according to a template.

The number of aspiration sites varies with testis size and ranges from 4 (to confirm obstruction) to 15 per testis (for nonobstructive azoospermia). FNA is performed with a sharp-beveled, 23-gauge, one-inch needle using the established suction cutting technique. Precise, gentle, in-and-out movements, varying from 5 mm to 8 mm, are used to aspirate tissue fragments. Ten to 30 needle excursions are made at each site. Suction is released, and then the tissue fragments are expelled onto a slide, gently smeared, and immediately fixed in 95% ethyl alcohol. Pressure is applied to each site for hemostasis. A routine Papanicolaou stain is performed. Smears are reviewed by experienced cytologists for (a) specimen adequacy (defined as at least 12 clusters of testis cells or at least 2000 well-dispersed testis cells) and (b) the presence or absence of mature sperm with tails. For immediate interpretation, fixed slides are stained with undiluted toluidine blue and read with brightfield microscopy after 15 seconds. Patients take an average of two pain pills after the procedure. Complications in over 800 patients have included one episode of hematospermia and, in another patient, post-operative pain for 7 days.

In another study, systematic testis FNA was used to determine which men were candidates for IVF-ICSI and to guide sperm retrieval procedures. Sperm retrieval guided by prior FNA maps was proposed as an alternative to standard sperm retrieval, which is generally performed on the same day as IVF and is associated with a significant chance of sperm retrieval failure. In 19 azoospermic men, sperm retrieval guided by prior FNA mapping found sufficient sperm for all eggs at IVF in 95% of cases. In addition, FNA-directed procedures enabled simple percutaneous FNA sperm retrieval in 20% of cases, and minimized the number of biopsies (mean 3.1) and the volume of testicular tissue (mean 72 mg) taken when open biopsies were required. Testis sparing procedures are particularly important in men with atrophic or solitary testes, and sperm retrieval guided by information from prior FNA maps can conserve testis tissue. Thus, this study confirmed that FNA maps can accurately identify azoospermic patients who are candidates for sperm retrieval and ICSI. In addition, it demonstrated that FNA maps can provide crucial information with respect to the precise location of sperm in the testis and can minimize the invasiveness of sperm retrieval.

Currently, two kinds of maps are performed in the evaluation of azoospermic infertile men. A compound map (>4 sites/testis) is typically performed as a diagnostic test to find sperm in failing testes. For this indication, men have testis atrophy, an elevated serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) level, or a prior biopsy revealing abnormal or absent spermatogenesis. A simple map (< 4 sites/testis) is used to confirm the clinical expectation of sperm production in men who may be obstructed and azoospermic. Simple FNA maps are offered to those who are planning to have reconstructive procedures (e.g., vasovasostomy) or sperm aspiration from the epididymis and who desire more complete information about spermatogenesis before proceeding with reconstruction or sperm retrieval. Regardless of the type of map, these procedures are generally diagnostic in nature. An experienced cytologist has a much better chance of finding sperm on a stained testis-tissue specimen with its higher resolution than does an andrology lab technician looking at the same tissue as part of a sperm retrieval procedure in an unstained specimen.

Biology of sperm production

From a comprehensive study of 118 consecutive azoospermic, infertile men who underwent FNA mapping, much has been learned about the geography of spermatogenesis in both normal (obstructed) and abnormal (nonobstructed) testes. In men with obstructive azoospermia, sperm is found in all sites and in all locations on the FNA map. However, in men with nonobstructive azoospermia, sperm is found in about 50% of cases. In the subgroup of men with no sperm on a prior testis biopsy, FNA maps revealed sperm in 27% of cases. This increased sensitivity in sperm detection is likely due to sampling a larger volume of the testis. There was also an intratesticular (site-to-site within the same testis) variation in sperm presence in 25% of cases and an intertesticular (side-to-side in the same individual) discordance rate of 19%. This suggests that bilateral examinations are crucial to fully informing men with nonobstructive azoospermia about opportunities for fatherhood, FNA mapping has also been used to determine whether particular geographic sites are more likely to have sperm than others. In one study, individual testis maps from each side were pooled, and from this analysis all FNA sites showed sperm at about the same frequency; there was no suggestion of sperm "hot spots" in nonobstructive testes. Thus, FNA mapping is a valuable diagnostic tool that not only guides the treatment of infertile men but can also provide a wealth of phenotypic information about the infertility condition.

Although the correlation of testis FNA cytology to testis biopsy histology is clear in the literature, how do the global organ findings from testis FNA mapping compare to biopsy histology? In other words, what is the chance of finding sperm on the map with each specific biopsy pattern? In a study of 87 patients, in whom a mean of 1.3 biopsies and 14 FNA sites were taken per patient, striking correlations were observed between FNA and histological results. Overall, sperm was found by FNA mapping in 52% of nonobstructive azoospermic patients. Pure histologic patterns of Sertoli cell-only and early maturation arrest were associated with a very poor likelihood of sperm detection (4–8%). In contrast, patients with other pure pattern histologies or mixed patterns had high rates of FNA sperm detection (77–100%). Thus, sperm detection with FNA showed wide variation depending on testis histology. In addition, certain histologic patterns may reflect a more global testicular dysfunction due to underlying genetic causes, and thus a poorer likelihood of sperm identification.

Testis FNA "Mapping" in the treatment of severe male infertility

In cases of infertility due to nonobstructive azoospermia, surgical sperm retrieval for IVF-ICSI is successful 40–60% of the time without prior knowledge of the geography of testis sperm production. With the addition of diagnostic FNA mapping, the rate of successful sperm retrieval can be increased substantially. However, high quality scientific evidence suggests that other approaches for sperm retrieval in non-obstructive azoospermia than TESA or aspiration approaches. In a review of 1,890 patients who had sperm retrieval results compared with aspiration found that testicular sperm extraction (TESE) with multiple biopsies was 2-fold more effective at finding sperm and microTESE (a microsurgical search for sperm within the testis) was 1.5-fold more effective at finding sperm From a review n=159 cases of nonobstructive azoospermia, one group observed that 44% of mapped cases required sperm retrieval by needle aspiration (TESA); 33% required open, directed surgical biopsies (TESE); and 23% needed microsurgically-assisted dissection of the entire testis parenchyma (mTESE) for successful sperm retrieval. In addition, the majority (78%) of these cases required only unilateral sperm retrieval to find sufficient sperm for IVF-ICSI. Overall, sufficient sperm for all oocytes retrieved was possible in 95% of cases with prior maps, ranging from 100% in simple aspiration cases to 80% of microdissection cases. In addition, among men who underwent a second sperm retrieval procedure, sperm was successfully retrieved in 91% of attempt; and among patients who had a third sperm retrieval, sperm was retrieved in 100% of attempts. Thus, knowledge of sperm location with FNA mapping can simplify and streamline sperm retrieval procedures in very difficult cases of nonobstructive azoospermia, but comparative studies suggest FNA is not as effective at retrieving sperm as more advanced techniques such as microTESE.

Summary

- Testis FNA cytology of the testis correlates well with testis biopsy histology in the evaluation of male infertility.

- Testis FNA cytology is rapid and safe and provides information not only on the presence or absence of sperm but, when applied in multiple areas like a "map", can precisely localize sperm production.

- Testis FNA cytology can direct sperm retrieval procedures and minimize the amount of testicular tissue removed.

- With wider sampling of the testis achieved with FNA cytology, the heterogeneity of sperm production can be more accurately defined and sperm retrieval procedures improved.

- Although assessment of architecture and the basement membrane is not possible with FNA, whole organ cytologic examination of seminiferous tubule patterns with mapping provides useful phenotypic information about severe male factor infertility.

- Best evidence suggests that FNA mapping is not the most effective technique for sperm retrieval in men with non-obstructive azoospermia

Footnotes

- Posner C. Die diagnostische Hodenpunktion. Berl Klin Wochenschr 1905;42b:1119-1121

- Hendricks FB, Lambird PA, Murph GP. Percutaneous needle biopsy of the testis. Fertil Steril.1969; 20:478-81

- Gottschalk-Sabag S, Glick T, Weiss DB. Fine needle aspiration of the testis and correlation with testicular open biopsy. Acta Cytol 1993;37:67-72.

- Mallidis C, Gordon Baker HW. Fine needle tissue aspiration biopsy of the testis. Fertil Steril 1994;61:367-375.

- Palermo G, Joris H, Devroey P et al. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet 1992; 340: 17.

- ^ Turek PJ, Ljung B-M, Cha I, Conaghan J. Diagnostic findings from testis fine needle aspiration mapping in obstructed and non-obstructed azoospermic men. J Urol 2000;163:1709-1716

- Damani MN, Master V, Meng MV, Turek PJ, Oates RM. Post-chemotherapy ejaculatory azoospermia: Fatherhood with sperm from testis tissue using intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Clin Oncology 2002; 20: 930-936.

- Firket J and Damiean-Gillet M. Value and importance of testicular biopsies in Klinefelter's syndrome. Acta Clin Belg 1951; 6:80-1.

- Levin HS. Testicular biopsy in the study of male infertility: its current usefulness, histologic techniques, and prospects for the future. Hum Pathol 1979;10:569-84.

- Johnsen SG. Testicular biopsy score count--a method for registration of spermatogenesis in human testes: normal values and results in 335 hypogonadal males. Hormones 1970;1:2-25.

- Cooperberg MR, Chi T, Jad A, Cha I, and PJ Turek. Variation in testis biopsy interpretation: implications for male infertility care in the era of intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril 2005; 84: 672-7.

- Papic Z, Katona G, Skrabalo Z: The cytologic identification and quantification of testicular cell subtypes. Acta Cytol 1988;32:697-706.

- Verma AK, Basu D, Jayaram G. Testicular cytology in azoospermia. Diag Cytopathol 1993;9:37-42.

- Batra VV, Khadgawat R, Agarwal A, Krishnani N, Mishra SK, Mithal A, Pandey R. Correlation of cell counts and indices in testicular FNAC with histology in male infertility. Acta Cytol 1999;43:617-623.

- ^ Meng MV, Cha I, Ljung B-M, Turek PJ. Testicular fine needle aspiration in infertile men: Correlation of cytologic pattern with histology on biopsy. Am J Surg Path 2001; 25: 71-79.

- Stock D, Misir V, Johnson S. Optimising FNA processing--a collection fluid allowing Giemsa, PAP and H & E staining, and facilitating thinprep, cytospin and direct smears and ancillary tests. Cytopathology. 2000; 11:523-4.

- ^ Turek PJ, Cha I, Ljung B-M. Systematic fine-needle aspiration of the testis: correlation to biopsy and results of organ "mapping" for mature sperm in azoospermic men. Urology 1997;49:743-748.

- Gottschalk-Sabag S, Glick T, Weiss DB. Fine needle aspiration of the testis and correlation with testicular open biopsy. Acta Cytol 1993;37:67-72 |

- ^ Ljung B-M. Techniques of aspiration and smear preparation. In Aspiration Biopsy: Cytologic Interpretation and Histological Bases. Second edition. Edited by LG Koss, S Woyke, W Olszewski. New York, Igaku-Shoin, 1992, pp 12-34.

- Turek PJ, Givens C, Schriock ED, Meng MV, Pederson RA, Conaghan J. Testis sperm extraction and intracytoplasmic sperm injection guided by prior fine needle aspiration mapping in nonobstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril 1999;71:552-557.

- Weiss DB, Gottschalk-Sabag S, Bar-On E, Zukerman Z, Gat Y, Bartoov B. Seminiferous tubule cytological pattern in infertile, azoospermic men in diagnosis and therapy. Harefuah 1997;132:614-618.

- Samli M, Sariyuce O, Basar M, Evrenkaya T. Evaluation of nonobstructive azoospermia with bilateral testicular biopsy. J Urol 1999;161:342.

- Meng MV, Cha, I, Ljung B-M, Turek PJ. Relationship between classic histological pattern and sperm findings on fine needle aspiration map in infertile men. Hum Reprod 2000;15:1973-1977.

- Tournaye H, Liu J, Nagy PZ, Camus M, Goossens A, Silber S, Van Steirtegham AC, Devroey P. Correlation between testicular histology and outcome after intracytoplasmic sperm injection using testicular spermatozoa. Hum Reprod 1996;11:127-132.

- Bernie AM, Mata DA, Ramasamy R, Schlegel PN. Comparison of microdissection testicular sperm extraction, conventional testicular sperm extraction, and testicular sperm aspiration for nonobstructive azoospermia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril . 2015 Nov;104(5):1099-103.e1-3.