| Battle of Rzhev | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battles of Rzhev on the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

Red Army artillery being redeployed through the mud, October 1942 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

As of 10 August 1942: Men: 352,867 in total (Ration Strength) Tanks (initially): 321 |

As of 30 July 1942: Men: 486,000 Tanks: 1,715 Aircraft: 1,100 As of 5 September 1942: Men: 334,808 Tanks: 412 Guns: 2,947 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 70,000 + | 300,000 + | ||||||

| Rzhev campaign | |

|---|---|

1942

1943

|

The Battle of Rzhev in the summer of 1942 was part of a series of battles that lasted 15 months in the center of the Eastern Front. It is known in Soviet history of World War II as the first Rzhev–Sychyovka offensive operation, which was defined as spanning from 30 July to 23 August 1942. However, it is widely documented that the fighting continued undiminished into September and did not finally cease until the beginning of October 1942. The Red Army suffered massive casualties for little gain during the fighting, giving the battle a notoriety reflected in its sobriquet: "The Rzhev Meat Grinder".

Rzhev lies 140 miles (230 kilometres) west of Moscow and was captured by the German Wehrmacht in Operation Typhoon in the autumn of 1941, which took them to the gates of Moscow. When the Soviet counteroffensive drove them back, Rzhev became a cornerstone of the Germans' defense. By mid-1942, the city stood at the apogee of a salient that protruded from the front lines, pointing in the general direction of Moscow. In July and August 1942, Stalin tasked two of his front commanders, General Georgy Zhukov (commanding the Western Front) and General Ivan Konev (commanding the Kalinin Front), to conduct an offensive to recapture Rzhev and strike a blow against Army Group Center that would push them away from Moscow. The attack would fall upon one of their main opponents of the winter battles, General Walter Model's 9th Army, which occupied the majority of the Rzhev salient.

The high losses and few gains made during the two-month struggle left a lasting impression on the Soviet soldiers who took part. In October, the strategic balance in the centre of the Eastern Front remained essentially unchanged. However, the German army had also suffered grievous losses, and whilst its defence had been tactically successful, it had achieved little more than maintaining the status quo. And although the offensive failed, Zhukov was given another chance to crush the Rzhev salient soon afterwards.

Background

The closing stages of the Battle of Moscow saw the formation of the Rzhev salient. The Soviet counter-offensive had driven the Wehrmacht from the outskirts of Moscow back more than 100 miles (160 kilometres), and had penetrated Army Group Centre's front in numerous places. Rzhev, a strategic crossroads and vital rail junction straddling the Volga, became the northern corner post of Army Group Centre's left wing. It was the only town of note for many miles and gave the 9th Army something to hang on to, in what otherwise seemed a wilderness of forest and swamp in all directions. The salient's existence was threatened at the very moment of its creation, when the Kalinin Front's 39th and 29th Armies opened a gap just west of Rzhev and thrust southwards into the German rear.

Just managing to keep the encroaching Soviet armies away from the vital rail link into Rzhev, the 9th Army, now commanded by General Model, managed to close the Rzhev gap, thereby cutting the Soviet supply lines and reducing their ability to deal a crippling blow to the whole army group. The Soviet counter-attack had run out of steam and the Germans recovered enough to mount several operations to clear up their rear area. In July 1942, Operation Seydlitz was mounted to trap and destroy the two Soviet armies and succeeded in little over a week in doing so, making the army group once more an almost credible threat to Moscow.

Prelude

Commanders

- General of Panzer Troops Heinrich von Vietinghoff was senior corps commander in the 9th Army in June 1942, and temporarily led the Army at the start of the battle, whilst Model was on convalescent leave. He later commanded 10th Army and Army Group C in Italy.

- General of Panzer Troops Walter Model had commanded 3rd Panzer division at the start of Operation Barbarossa, and had become commander of XXXXI Motorised Corps in October 1941. He had shown great resolve in the defensive winter battles, and was promoted to 9th Army commander on 12 January 1942. He proved to be a tough soldier and a defensive specialist. Respected by Hitler, he was promoted to field marshal in March 1944.

- Georgy Zhukov was Chief of the General Staff when the Germans invaded the Soviet Union but, following a disagreement with Stalin concerning the defense of Kiev, was demoted to command of the Reserve Front. He became a troubleshooter, commanding the Leningrad Front in the autumn, and back to Moscow to conduct its defense and counteroffensive. Zhukov remained in the central sector, and he argued in the spring of 1942 that the Moscow axis was the most critical and that Army Group Center posed the greatest threat to the Soviet Union. To him, the German forces at Rzhev "represented a dagger pointed at Moscow". Zhukov convinced Stalin to give him the extra forces he needed. He commanded the Western Front's attacks until, in the latter part of August, Zhukov became deputy supreme commander and was transferred to Stalingrad. Later, he continued to hold the highest commands in the Soviet Army, and became a Marshal of the Soviet Union in January 1943. Zhukov remained always in the thick of the fighting until the very end of the war, commanding the 1st Belorussian Front in the assault on Berlin, still in rivalry with Konev, who commanded the 1st Ukrainian Front in the final battle.

- Colonel-General Ivan Konev began the war against Germany commanding the 19th Army, which become encircled around Vitebsk in the first weeks of the conflict. Stalin blamed Konev for the disaster but Zhukov intervened and ensured his survival and promotion to front commander. He went on to command the Kalinin Front in the winter battles around Moscow with distinction, and still commanded the Kalinin Front at the start of the Rzhev Operation. When Zhukov was promoted to deputy supreme commander, Konev was given overall responsibility for the continuing offensive.

Battlefield

The summer months of 1942 in the Rzhev area were warm, with long days and a high sun which allowed the area to dry out after the spring thaw. Rzhev had flat, rolling country, with thick forests and patches of swamp. The neighborhood of Rzhev had open farmed land with a dense network of small village communities, which were often ribbons of houses along the roadside. The roads were mostly mud tracks that became almost impassible in the spring and autumn rains, but normally dried out in summer. Rainfall was typically moderate, but the summer months of 1942 had seen unusually heavy and persistent rainfall.

Of the Red Army's objectives, the city of Rzhev was by far the largest, with over 50,000 inhabitants. Zubtsov had under 5,000; Pogoreloye Gorodishche had but 2,500. Karmanovo, to be the scene of much bitter fighting, was in reality simply a large village.

The Volga is the longest river in Europe, and in both the central sector of the Eastern Front at Rzhev and at the southern sector at Stalingrad, German and Soviet armies struggled for mastery of its banks. Both Rzhev and Zubtsov straddled the river, which was 130 m wide at this point.

Of major significance to both attacker and defender were tributaries of the Volga, the Dërzha, Gzhat, Osuga, and Vazuza Rivers, which ran south to north across the line of the Soviet attack. These were normally docile and fordable at this time of year, but they had become swollen with the July rains and had risen to the depth of over 2 m. By August they constituted a major impediment to Zhukov's Western Front's attack. His forces would have to cross the Dërzha on the start line and then a further one or even two flooded rivers to reach their final objectives.

From the German point of view, the most important objective was the Viazma–Rzhev rail line, the loss of which would sever their supply line to Rzhev and render the defense of the whole salient untenable. Also important from the Soviet perspective was the Zubtov–Shakhovskaya rail line, which ran in the direction of their intended advance, and could be used to ferry supplies forward.

Opposing forces

German order of battle

The strength of 9th Army varied considerably during mid-1942, as the Army Group shifted forces between its armies for use in different operations and defensive commitments. In early July the 9th Army was reinforced so that it could conduct Operation Seydlitz. It reached a total of 22 divisions, including four panzer divisions organised in five higher corps headquarters. After the successful conclusion of the operation the army group shifted many of its offensive-capable divisions southward for its next planned attack against the Sukhimchi bulge, leaving the 9th Army at the end of July with 16 infantry divisions, organised in three corps, with 14 divisions in the line, one in reserve and another in transit.

Nearly all the divisions of Army Group Center had seen heavy winter fighting, which had sapped their fighting strength. According to rehabilitation reports, the necessity to hold the line and the "unabated intensity of defensive fighting" meant that the divisions could only be partially restored to strength. They would have limited mobility and reduced combat efficiency, with the greatest gap being the shortage of motor vehicles and horses.

Following the collapse of its front east of Rzhev, the army was rapidly reinforced, but the continual strain of persistent Russian attacks led General Model to demand further support. By the end of September, the army consisted of 25 divisions—half the army group strength—including 20 infantry and four panzer, as well as the Großdeutschland division.

| Order of battle: 9 Army – 30 July 1942 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army | Army Commander | Corps | Corps Commander | Divisions | |

| 9th Army | Heinrich von Vietinghoff | XXIII Army Corps | Carl Hilpert | 197th, 246th, 86th, 110th, 129th, and 253rd. | |

| VI Army Corps | Bruno Bieler | 206th, 251st, 87th, and 256th. | |||

| XXXXVI Panzer Corps | Hans Zorn | 14th Mot., 161st; 36th Mot., and 342nd. | |||

| Army reserve | 6th; Parts of 328th. | ||||

| Order of battle: 9 Army – 2 October 1942 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army | Army Commander | Corps | Corps Commander | Divisions | |

| 9th Army | Walter Model | XXIII Army Corps | Carl Hilpert | 197th, 246th, 86th, 110th, and 253rd. | |

| VI Army Corps | Bruno Bieler | 206th, 251st, 87th, and 6th. | |||

| XXVII Army Corps | Walter Weiß | 256th, 14th Mot., 72nd, 95th, and 129th. | |||

| XXXIX Panzer Corps | Hans-Jürgen von Arnim | 102nd, 5th PD, 1st PD, and 78th. | |||

| XXXXVI Panzer Corps | Hans Zorn | 2nd PD, 36th Mot., and 342nd. | |||

| Army reserve | 161st; 328th, 9th PD, and Großdeutschland Division | ||||

Soviet order of battle

Stalin and his command group, the Stavka, sought to develop strong concentrations of forces which would attack across narrow sectors with heavy assistance from supporting arms. For example, the Kalinin Front was told to "create a shock group" of no less than 11 rifle divisions and three rifle brigades, eight tank brigades and 10 RGK artillery regiments. To achieve these high force concentrations, the Stavka handed over from its reserve to the Kalinin Front, five rifle divisions, six tank brigades, two RGK artillery regiments of 152 mm guns, four antitank artillery regiments, and 10 M-30 battalions.

Support for the operation was to be on a huge scale. In an attempt to wrest air superiority from the Germans, Colonel General Alexander Novikov, commander of the Soviet Air Forces, was told to concentrate 1100 aircraft in the attack sectors, including 600 fighters. They sought to smash through the German front by implementing the idea of "artillery attack" to maximize firepower using massed collections of guns, mortars and rocket launchers. 30th Army, for example, concentrated 1323 guns and mortars along its 6.2 miles (10.0 kilometres) stretch, achieving a density of 140 tubes per kilometer. The correlation of infantry in the attack sectors was calculated as between 3–4:1 in the 30th, 31st, and 33rd Army sectors and about 7:1 in the 20th and 5th Army sectors. The artillery advantage was overwhelming, with 6–7:1 for all armies except for the 30th, where it was calculated to be 2:1.

The majority of the Soviet tank strength still lay in separate tank brigades that directly supported the infantry. 30th Army started the offensive with nine tank brigades with 390 tanks, 31st Army with six tank brigades with 274 tanks, and 20th Army with five tank brigades and 255 tanks. Behind these army-level forces were newly created tank corps, the 6th and 8th to the rear of 20th Army, and 5th Tank Corps behind 33rd Army.

The tank corps had been created between March and May around a kernel of existing tank brigades and new men from the training establishments. They were supplied with the best tanks available, but lacked artillery and support units. Initially, even trucks were in short supply. Although formed around a core of veterans from the winter fighting, these units had supported the infantry armies and were not yet used to independent action, and were not able to fulfill their exploitation role. Their leaders were experienced commanders, many of whom were cautious of German armored units from the previous year's campaigning and tended to overestimate German strength.

| Order of battle: Kalinin Front (Ivan Konev) and Western Front (Georgy Zhukov) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Army | Army Commander | Corps | Divisions | ||

| 30th Army | Dmitry Lelyushenko | 2nd and 16th Guards Rifle Divisions, 52, 78, 111, 220th, 343rd, 379th Rifle Divisions 9 Tank brigades incl. 35, 238 and 240 Tank Brigades in the Army mobile group | |||

| 29th Army | Vasily Shvetsov | ||||

| 31st Army | V. S. Polenov | 20th Guards Rifle Division, 88th, 118, 164, 239th, 247, 336th rifle divisions 6 tank brigades 34, 71, 212, and 92, 101, 145 in the mobile group. | |||

| 20th Army | Max Reyter | 251st, 331th, 354th, 82nd, 312th and 415th Rifle Divisions 40th rifle brigade 5 tank Brigades 17, 20, plus 11, 188, 213 in the mobile group. | |||

| 20th Army | 8th Guards Rifle Corps | 26th Guards Rifle Division, 129, 148, 150, 153 rifle brigades | |||

| 5th Army | Ivan Fedyuninsky | 3rd Guards Motorized Rifle Division, 42nd Guards Rifle Division, 19th, 28th Rifle Divisions, 28, 35 and 49 rifle brigades, and 120, 161, 154 tank brigades. | |||

| 33rd Army | Mikhail Khozin | 50th, 53rd, 110th, 113th, 160th, 222nd Rifle Divisions, 112, 120, 125, 125 rifle brigades, 18, 80, 248 tank brigades | |||

| 33rd Army | 7th Guards Rifle Corps | 5th, 30th Guards Rifle Divisions, 17th Rifle Division | |||

| Western Front | 5th, 6th, 8th Tank Corps, 2nd Guards Cavalry Corps | ||||

Battle

Kalinin Front attacks

The front line, which had not changed in this sector since January, had given ample time for Soviet intelligence and planners to pin point the German forward defenses and plan their destruction or suppression. The situation behind the front lines was more sketchy to the attackers, and the Germans, on Model's orders, had not been idle, and had constructed a secondary line outside of Rzhev and a final belt of defenses on the cities outskirts.

The terrain was in places low and prone to swampiness, with the villages constructed on the higher and drier elevations. These were turned by the Wehrmacht into strongholds, and linked by trench lines and defences. They were described by Soviet accounts as having solid minefields, networks of bunkers, and barbed wire laid out in dense lines. Additionally, the unusually wet summer and continued downpours of late July and August greatly enhanced the defenses, hindering the deployment of both tanks and artillery for the Russians, who proved unable to bring to bear their superiority in these areas. The distance to Rzhev was 7.5 miles (12 km) which the attacking forces hoped to cover in a rapid advance reaching the city in two days and fully occupying it by the third.

To accomplish this mission, General Major D. D. Lelyschenko, 30th Army commander, had received massive reinforcements, and had four rifle divisions lined up along narrow attack sectors, pointing straight at Rzhev, and a further two flanking rifle divisions who would shove the shoulders of the German defense aside. Behind these he had two more rifle divisions ready to reinforce the main attack, and another behind the flank. The six rifle divisions in line would strike at the junction of the German 87th and 256th Infantry Divisions and pierce the defenses along a 6-mile (10 km) front. Each of the main attacking divisions was reinforced by a tank brigade and backed by an impressive array of army and front level artillery, as well as Katyusha rocket launchers. In all, the 30th Army deployed 390 tanks, 1323 guns and mortars, and 80 rocket launchers for the attack.

30 July 1942

At 6.30 am on 30 July, in the low light of early morning, the 30th Army artillery opened fire in a tumultuous roar. The artillery commander of the Kalinin Front, Colonel-General NM Khlebnikov, recalled: "The power of fire impact was so great that the German artillery after several faltering attempts to answer fire with fire stopped. First two positions of the main strip enemy defenses have been destroyed, troops occupying them – almost completely destroyed."

After an hour and a half of bombardment, at 8am, the rifle divisions attacked. In spite of the sudden onset of more heavy rain, and with infantrymen sometimes wading through sodden fields with water up to their knees, the attack quickly acquired momentum.

The 16th Guards Rifle Division in the center overran the forward trenches already in the first hour, and the fortified villages of the second position soon after, and by 1pm its men were deep in the German rear and already approaching the village of Polunino, halfway to Rzhev. To its right, the 379th and the 111th Rifle Divisions also smashed into the German front line, penetrating into the depths and capturing four batteries of 87th Divisional artillery.

The Soviet 30th Army had broken through on a front nine kilometers and a reached a depth of 4 miles (6.4 km), but already late on the first day its spearheads were brought to a halt by German counter-attacks, and ominous signs of the difficulties ahead started to appear. In the breakthrough sectors the supporting tanks were lagging behind, and many remained mired in the mud; the riflemen had come up against prepared German lines, and upon digging in found their trenches immediately filled with water.

Generalleutnant Paul Danhauser, commanding the German 256th Infantry Division, committed his pioneer and reconnaissance battalion in a counter-attack from Polunino and committed his last reserve, the division's field replacement battalion, to try and fill his open flank. Of his original front line, anchored by Strong-point Emma near the old 256-87 division boundary, nearly all was still in German hands in spite of severe pressure from the Soviet flanking attack. The 9th Army had reluctantly handed over the 54th Motorcycle Battalion, the 14th Motorized Division's only reserve, to fill the hole in the 256th Division's left flank.

31 July – 6 August 1942

The next morning the Soviet attackers expected to be able to resume the advance, but had difficulties coordinating their various arms. Numerous tank breakdowns reduced the numbers of supporting armour to a handful, which left them vulnerable to German panzerjäger defenses. Without massed artillery support, the German defensive positions remained intact. The Germans had managed to plug the gaps with divisional reserves and were now fighting desperate battles, hanging on until further help could arrive. By evening, battalions from the 6th Infantry Division's 18th and 58th Infantry Regiments began arriving in the vital central sector around Polunino and a small elevation west of the village, Hill 200. For the Soviets, the day failed to deliver anything except heavy losses. The 16th Guards Rifle Division began a series of attacks on the village of Polunino, which it continued all day, and suffered over 1000 casualties. As its divisional journal laconically stated, 'the attack was not successful'. The frontal attacks of the 31 July set the pattern for the days to come; Soviet commanders did not have the latitude (or sometimes the imagination) to develop flexible tactics and often rigidly executed orders from above, even if it meant attacking head on across the same ground for days or even weeks at a time.

By 3 August the Germans were already counting the Soviet losses and wondering how much longer the Soviet formations could keep going. They estimated correctly that many rifle divisions had suffered thousands of casualties, but also noted signs of new men arriving to fill some of the depleted ranks. Three days later a frustrated Stavka issued a pronouncement, demanding 30th Army provide solutions to a variety of perceived problems, including weak leadership, failure to mass tanks and poor ammunition supply to the artillery. After the success of the first day, seven days of attacks had achieved nothing and the 30th Army called a halt in order to regroup and reorganize.

10–30 August 1942

On 10 August the Soviet troops attacked the flank of the 256th with renewed ferocity. The 220th Rifle Division, which had been battering away at the stubborn defence of the 256th Infantry Division since 30 July and had lost 877 dead and 3083 wounded in the first four days alone, finally captured the key village of Belkovo on the 12 August. Its divisional commander, Colonel Stanislav Poplavsky, saw that 'the fields were full with the bodies of the dead.' The day before, Gilyarovich had received a call from the Front commander, Konev, who had suggested the supporting tank brigade be pulled out to lead the next infantry attack. But his attached armour, as in so many other sectors, had become mired in the mud and only four tanks could be extracted.

But in other sectors new rifle formations had been brought up. Strong-point Emma, the vital cornerstone of the defence that had held out for two weeks, fell; tanks from the Soviet 255 Tank Brigade were roaming unhindered in its rear. Some German defenders noted that the Soviet tankers were employing new tactics: 'staying out of the reach of our anti-tank guns, they systematically shot up every position, which had a demoralizing effect on the infantry, causing tank-panic.'

The continued Russian tank attacks were in danger of swamping the defense, but Soviet infantry tactics remained crude with dense masses of men rushing forward, shouting 'Hurrah'. Replacements were often thrown directly into battle directly from the trains without orientation or any time to get to know their officers or their outfit.

Model, just returning from convalescent leave, saw that the German defense had bent but not completely broken. He issued 'not a step back' orders and funnelled in all available reserves, including scratch battle groups thrown together from troops returning on leave trains. At the same time, he demanded additional reinforcements from higher commands.

Red Army losses were catastrophic, but the German defenders were also under severe strain. The constant attacks exhausted the troops, and break-ins had to be constantly driven back by local counterattacks. The 481st Infantry Regiment was now reduced to 120 fighting troops, mostly attached to Battle Group Mummert, which was composed of units thrown together from four different divisions. The antitank (Panzerjäger) battalions were the key to the defense against tanks, but the guns could not be everywhere. It was common for the infantry to use grenade bundles or mines to deal with tanks overrunning their trenches. These attacks required great individual daring.

The gains of the flanking attacks, although meager, did finally open a new opportunity east of Pultuno, which the 2nd Guards Rifle division was able to exploit. Overrunning a sector which ran across swampy and forested ground, the division in three days fought its way through to the Rzhev airfield on the outskirts of the city. Counter-attacks stabilized the front, and Model allowed the 256th Infantry and 14th Motorized Divisions, whose positions now bulged out into Soviet lines, to pull back across the Volga's western bank. The Soviets, now in easy artillery range, started to pound the city, which together with air strikes reduced its buildings to smouldering ruins.

By the end of the month, the stubborn German defense of Putino came to an end as they finally withdrew under heavy pressure, and took up new defensive positions on the Rzhev perimeter.

Western Front attacks

The attack by the Western Front, planned for 2 August, was delayed by another two days, mainly for the additional delays imposed by the abysmal weather. Zhukov planned to penetrate the line at Pogoreloye Gorodishche, and advance towards the Vazuza river, destroying the defending forces of the XXXXVI Panzer Corps, known as the Zubtsov Karmanovo grouping in the process. The front mobile group, 6th and 8th Tanks Corps and the 2nd Guards Cavalry Corps, would be committed towards Sychevka with the 20th Army while the 31st Army co-operated with the Kalinin Front's forces to capture Rzhev.

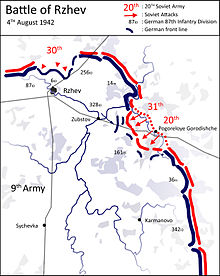

4 August 1942

In the early morning hours of 4 August 1942, General Zukov unleashed the Western Front's attack against the Rzhev salient. The offensive began with a massive preliminary bombardment. A concentration of artillery and mortars along a narrow front rained down shells and bombs on the German positions for nearly one and a half hours, and was followed by a pause in which Soviet aircraft laid smoke along the front line. But the lull was a ruse to lure the German defenders back into their forward trenches to suffer the final crescendo, which was topped off by a volley from Katyusha rocket launchers.

The energy of the fire-storm in many places destroyed the German wire entanglements, and bunkers and fixed positions lay smashed. The attack battalions from the Soviet rifle divisions, using rafts, boats and ferries to cross the swollen river Derzha, secured the forward German line within an hour and with little loss.

Pogoreloye Gorodishche, a battalion stronghold of the 161st Division's 364th Infantry Regiment and one of the Soviet 20th Army's main initial objectives, was quickly outflanked and then cut off by Soviet infantry. Soon after midday, aided by another sharp artillery strike and supported by tanks, Russian riflemen stormed into the position from three directions and overwhelmed the garrison, capturing 87 officers and men and leaving many more dead.

South of Pogoreloye Gorodishche, the 331st Rifle Division rapidly captured the forward trench line and moved swiftly on to take Gubinka, a village in the secondary line. Until that morning it had been the location of 336 Infantry Regiment's headquarters, which was found abandoned and strewn with staff documents and discarded equipment. All along the 161st Division's entire front, its soldiers had been attacked in overwhelming force, its defences had crumbled and given way, and its remaining soldiers were in full retreat. The 20th and 31st Soviet Armies had torn a gaping hole in the German front, and by evening their rifle divisions and supporting Tank Brigades had advanced 5 miles (8.0 km) into the German lines.

The German command were quick to realize the dangers of the new Soviet offensive, and Hitler immediately released five divisions which had been held in reserve for Operation Whirlwind, the planned attack on the Sukhinichi bulge. These included 1st, 2nd and 5th Panzer Divisions and 102nd and 78th Infantry Divisions. Von Vietinghoff, acting 9th Army commander, had already committed what reserves he had against the Kalinin Front's attack and had virtually nothing on hand to stop the new Soviet advance except Army schools, teenage helpers and a few flak guns, which he positioned at strategic points. These were not going to stop Soviet tanks for very long; German defences were wide open until the arrival of the reinforcement divisions.

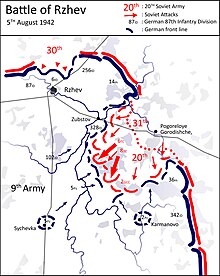

5–9 August 1942

On the morning of 5 August, in what Halder termed a "very wide and deep penetration," the Soviet rifle divisions pushed on into the depth of German positions against negligible opposition. However, as the Soviet commands began to commit their armoured units forward, problems started to emerge.

Crossing points along the river Darzha were interdicted by Luftwaffe attacks and complicated by the high water and the strong current. The Tank Corps were taking hours to get across even fractions of their forces. The roads, saturated by the incessant rains, rapidly deteriorated and were clogged with traffic of all sorts, some of which became hopelessly mired in the mud and could not move. Re-supply carts, artillery, and tanks were stuck in traffic jams and became disorganized and disorientated. 11th Tank Brigade, part of 20th Army mobile group, became lost and only turned up days later fighting in the wrong sector. The accompanying motorcyclists, who were attached to the Army mobile group, were unable to move their machines forward, and had to abandon them; the riders advanced instead as ordinary infantry, trudging slowly forward through the mud.

Nevertheless, 20th Army infantry advanced another 18 miles (30 km) and was joined by nightfall by the foremost parts of both 6th and 8th Tank Corps. These forces were approaching the rivers Vazuza and Gzhat, but as light faded on the 5 August they began to make contact with fresh enemy units. These came primarily from 5th Panzer Division, which had been closest to the breakthrough area, and had been rushed to the crucial sector north of Sychevka, where its forward elements crossed the Vazuza at Chlepen and fanned out, hurriedly occupying defensive positions.

At the southern corner-post of the breakthrough, 36th Motorized Division's stubborn defence had been the only bright spot for 9th Army on the 4 August, but its opponent, the Soviet 8th Guards Rifle Corps, had quickly infiltrated forces around the division's northern flank and into its rear.

The following day, the Soviets broke through from the north with tanks and infantry, swept around and over a battery of divisional artillery, 105 mm howitzers, and reached the tiny community of Dolgie Niwuj, some two kilometers from the 36th Motorised Divisional headquarters in Voskresenskoye (Woskresenskoje). Generalmajor Gollnick, the divisional commander, watched the houses of Dolgie Niwuj go up in flames and started to reorganize his defences to cope with what was to be but the first of a series of crises for the division.

Soviet infantry from the 20th Army was pushing past his rear towards Kamanovo, but were thwarted by the arrival of 2nd Panzer Division, which pushed them back and sent tanks and panzer grenadiers to the aid of Gollnick.

Meanwhile, for the 5th Panzer Division, the 6 August proved to be a day of crises. Both of its flanks were 'hanging in the air', and it was assailed along its entire newly acquired front by infantry and tanks, some of which broke through to harass supply units and artillery positions. 14th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had deployed both its battalions in line, only to have them badly mauled. Its 2nd Battalion became encircled and had to fight its way out, with a supporting tank company losing eight tanks fending off attacks by T34s which seemed to come from all sides. The intense fighting cost the 5th Panzer Division 285 casualties on this day alone, but limited further Russian advance to only 2 miles (3.2 km).

Substantial Russian forces were getting forward so that by the 8 August, the Soviet 20th Army had introduced over 600 tanks into its sector. As additional forces from both sides joined the battle, the intensity of the fighting grew, but the forward momentum of the attackers first slackened, then stopped. Mounted regiments from 2nd Guards Cavalry Corps reached the river Gzhat, exploiting the gap between the 5th and 2nd Panzer Divisions, and were able to ford it and carve out a bridgehead on the southern bank. Its advance was checked by the arrival of 1st Panzer Division, which attacked and drove the line back. Likewise, 6th Tank Corps reached and crossed the Vazuza along with some rifle forces, but once across, was met with fierce counter-attacks and air-strikes, which prevented further advance.

Soviet difficulties persisted. 20th Army found its headquarters communications not up to the task and had difficulty coordinating its many rifle units and cooperating with the front's mobile group. Because of the ongoing logistical problems, resupply was difficult; 8th Tank Corps complained of running low on fuel and ammunition, which hindered its operations. The 17th Tank Brigade found that not enough fuel were getting through to keep all the tanks in action, and artillery was having to be held back in favour of advancing combat units.

On the other side, to prevent a breakthrough, von Vietinghoff was having to throw his infantry and armoured units piecemeal into combat immediately upon arrival, but by 8 August, had managed to erect a firm cordon around the Western Front's entire penetration.

With a breakthrough towards Sychevka looking increasingly unlikely in the face of German reinforcements, Zhukov ordered the 20th Army to extract 8th Tank Corps and realign it to the south, to cooperate with renewed 5th Army attacks. There was some improvement in the weather which finally allowed the roads to dry sufficiently to bring up ammunition, and Soviet logistics were further improved by the restoration of the rail line as far as Pogoreloye Gorodishche.

8th Tank Corps was still tied up with combat against the 1st Panzer Division and could only extract 49 of its tanks for the attack. Nevertheless, on August 11, after a brisk artillery preparation, it struck, advanced 3 miles (5 km) and captured the village of Jelnia. Its opponent, the 2nd Panzer Division, noted 'especially heavy attacks' on that day and had just received a delivery of new PzKpfw IV tanks, which it committed immediately into the fighting.

The 5th Army had only managed to make a shallow dent in the line on 8 August when its first attack had been rapidly halted by German reinforcements, now rejoined the struggle to add to the pressure on Zorn's XXXXVI Panzer Corps from the east. After this 20th and 5th Army continued to attack, grinding a mile or two forward every day with bitter fighting for every village. The Germans, they complained, were continually developing their trench systems, which were backed by concealed mortar and anti-tank gun positions, and protected by minefields and booby-trapped obstacles.

Finally, on 23 August, Kamanovo fell. Thereafter, 20th Soviet Army found it could advance no further against a shortened and strengthened German line until, on 8 September, it went over to the defensive.

September 1942

On 26 August, Zhukov was appointed Deputy Commander-in-Chief, and transferred to the Stalingrad Front, so command of the Western Front was handed to Konev. To keep unified command arrangements, Kalinin Front's 30th and 29th Armies were subordinated to Western Front authority.

Once he had taken over, Konev saw that 'troops were dwindling in number and shells were few' and called for a halt to reorganize, restock ammunition, repair tanks and aircraft. He decided to launch the 31st and 29th Armies from the south east and 30th again from the north and 'close the encirclement ring around Rzhev'.

After its initial breakthrough, 31st Army had achieved a steady but unspectacular advance in its sector against German infantry, pushing them back step by step, and inflicting a steady drain on German resources but suffering greatly itself. By 23 August it captured one of the main objectives of the offensive, taking the southern half of Zubtsov. Then, its units reached the river Vazuza and carved out a shallow bridgehead on the western bank. Konev took the 6th Tank out from 20th Army and put it back in the line just below Zubtsov utilizing 31st Army's bridgehead. The attack was planned for 9 September, when sufficient ammunition had been brought up.

6th Tank Corps assembled in the forests, and at dawn of the 9th, after a half hour's artillery barrage, attacked alongside infantry from the 31st Army. Achieving immediate success it cut through a dilapidated infantry battalion from 11th Infantry Regiment seized two villages. Moving on, it captured the village of Michejewo, threatening a complete breakthrough. After some hesitation and much telephoning, Hitler released the Großdeutschland division for a counter-attack.

Losses

The participating Soviet armies suffered 290,000 casualties in the Rzhev fighting, a figure that covers the main army groupings for the period of their offensive commitments, but does not cover the independent corps nor air force losses; overall losses were in excess of 300,000. Some sources, such as some reports from the participant armies themselves, give higher figures for their casualties than those recorded by the Front.

The rifle divisions of the attacking armies had to receive additional men to continue to attack due to the high attrition rate in men. To maintain the offensive into September, Konev requested 20,000 replacements for just two of the armies involved. By 10 September the Soviet armies had been decimated: losses had reduced them to half-strength, with 184,265 men and 306 tanks.

| Army | Duration of operation | Total losses in the operation |

|---|---|---|

| 30th Army | August–September 1942 | 99,820 |

| 29th Army | August–September 1942 | 16,267 |

| 20th Army | 4 August–10 September 1942 | 60,453 |

| 31st Army | 4 August–15 September 1942 | 43,321 |

| 5th Army | 7 August–15 September 1942 | 28,984 |

| 33rd Army | 10 August–15 September 1942 | 42,327 |

| Total 291,172 |

Table of Soviet losses

German losses in the 9th Army by 17 August already numbered 20,000. On 1 September, von Kluge flew to the Fuehrer Headquarters to relay what Model had told him the day before: 9th Army was at the point of collapse. Its casualties were up to 42,000 and rising at a rate close to 2,000 a day. Hitler promised some modest reinforcements, possibly including the Großdeutschland division. "Someone," he stated, "must collapse. It will not be us!"

By mid-September, the German infantry divisions in the thick of the fighting had suffered up to 40,000 casualties, and, in the case of the hard-hit 161st Infantry Division, over 6,000. The Panzer divisions all had lost between 1,500 and 2,000 casualties, and most of the tanks they started the battle with. Overall, the 9th Army toll lay at above 53,000, including in excess of 1,500 officers. Additionally, in the 3rd Panzer Army sector, casualty reports for around the time of the Soviet attack list over 10,000 losses.

References

- Aussenstelle OKH/Gen. Qu. Befehlsstelle Mitte/Qu 1. Zahlengrundlagen. Stärken von 10.8.1942. Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv (BA-MA) RH 3//182, fol. 345.

- Jentz 2004, pp. 235–237: Total tanks possessed by 1st, 2nd, 5th and 20th Panzer Divisions, which belonged to the 9th Army, at the end of June early July.

- Alfred Price, The Luftwaffe (World War II Data Book) as of 27 July 1942 (figure in brackets = operational) aircraft available to Luftwaffen Kommando Ost

- Gerasimova 2013, pp. 77–78.

- Gerasimova 2013, p. 87.

- ^ Gerasimova 2013, p. 168.

- Forczyk 2006, p. 89.

- Gerasimova 2013, pp. 96–99.

- Glantz 1999b, p. 12.

- Glantz 1999b, p. 18.

- ^ Ziemke 1987, Kindle Location 2764.

- ^ Ziemke 1987, Kindle Location 3733.

- Mitcham 2000, p. 67.

- ^ Mitcham 2009, p. 254.

- Roberts, Hitler and Churchill: Secrets of Leadership

- Chaney 1996, p. 122.

- ^ Glantz 1999a, p. 151.

- Forczyk 2012, pp. 11–55.

- ^ Forczyk 2006, p. 19.

- Weather data for Rzhev on ru.wikipedia.org (Russian text)

- Geographical Dictionary of the World, entry on Volga, p. 1938.

- see Railway line Lihoslavl – Viazma

- ^ Tessin, Verbände und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939–1945, 9 A Kommandoberhorden, p. 123.

- ^ Grant, The German Campaign in Russia, planning and operations, p. 130.

- ^ Glantz 1999a, p. 150.

- Beshanov 2008, p. 319.

- ^ Gerasimova 2013, p. 78.

- Beshanov 2008, Chapter: 'Rzhev and Vyazma'.

- Forczyk 2014, p. 171-172.

- Forczyk 2014, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Beshanov 2008, p. 318.

- Beshanov 2008, p. 332.

- ^ Glantz 1999a, p. 157.

- Newton 2005, p. 197.

- ^ Isaev 2006.

- Beshanov 2008, p. 320.

- ^ Beshanov 2008, Chapter – 'Rzhev and Vyazma'.

- ^ Gerasimova 2013, p. 80.

- ^ Extracts from the journal of hostilities 16th Guards Rifle Division, July 30 & 31

- Halder War Diary, entry 30 July 1942, p. 649.

- LA Sorin, Kondratiev, P. Karintsev, Smirnov, E. Ozhogin . Rzhevskaya war of 1941–1943. / History of Rzhev. – Rzhev: 2000 – pp. 149–222. Chapter 13 'fight in the swamp'

- ^ Selz 1970, pp. 122–132.

- Gerasimova 2013, p. 101: Quoted conversation between Stalin and Antonov

- Gorbachevsky 2009, p. 434.

- Gerasimova 2013, p. 209.

- ^ LA Sorin, Kondratiev, P. Karintsev, Smirnov, E. Ozhogin . Battles of Rzhev from 1941–1943.Chapter 13 'Fight in the swamp'

- ^ Haupt 1983, p. 193.

- The battle for hill 200, 3 August

- Gerasimova 2013, p. 100.

- Gorbachevsky 2009, p. 139: Replacements had been brought up in rail cars, unloaded and sent into the attack the same day

- Haupt 1983, p. 198.

- ^ History of Rzhev

- Glantz 1999a, p. 152.

- ^ Sadalov, Offensive operations of the 20th Army

- Ziemke 1987, Kindle Location 8830.

- Ziemke, Moscow to Stalingrad, Chapter XX Summer On The Static Fronts. Also von Plato, History of 5th Panzer Division and Stoves, 1 Panzer Division

- Burdick 1988, p. 654.

- Getman 1973.

- ^ Gerasimova 2013, p. 85.

- ^ von Plato 1998, pp. 234–237.

- ^ Conrady, Rshew 1942/1943, pp. 88–100.

- ^ Jentz 2004, p. 243.

- ^ Glantz 1999a, p. 156.

- Yaroslavovna and Chernov, article '70th anniversary' see external reference

- Strauss 2005.

- ^ Gerasimova 2013, p. 94.

- ^ Gerasimova 2013, p. 98.

- Glantz 1999a, p. 171.

- Ziemke 1987, Kindle Locations 8900–8901.

- Ziemke 1987, Kindle Locations 8922–8924.

- 9th Army report dated 10 September 1942, Geramisova archives

- Heeresarzt 10-Day Casualty Reports per Army/Army Group, 1942 Archived 2015-12-28 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

English sources

- Burdick, Charles (1988). The Halder War Diary, 1939–1942. Presidio. ISBN 978-0891413028.

- Chaney, Otto Preston (1996). Zhukov. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806128078.

- Forczyk, Robert (2006). Moscow 1941: Hitler's First Defeat. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-017-8.

- Forczyk, Robert (2012). Georgy Zhukov. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-556-4.

- Forczyk, Robert (2014). Tank Warfare on the Eastern Front 1941–1942: Schwerpunkt. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-78159-008-9.

- Gerasimova, Svetlana (2013). The Rzhev Slaughterhouse. Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-908916-51-8.

- Glantz, David M. (1999a). Forgotten Battles of the German-Soviet War Vol. III.

- Glantz, David M. (1999b). Zhukov's Greatest Defeat: The Red Army's Epic Disaster in Operation Mars, 1942. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0944-4.

- Gorbachevsky, Boris (2009). Through the Maelstrom: A Red Army Soldier's War on the Eastern Front, 1942–1945. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0700616053.

- Jentz, Thomas L. (2004). Panzertruppen: Vol 1. Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0887409158.

- Mikhin, Petr (2011). Guns Against the Reich: Memoirs of a Soviet Artillery Officer on the Eastern Front. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0811709088.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (2000). The Panzer Legions. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3353-3.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (2009). Men of Barbarossa: Commanders of the German Invasion of Russia, 1941. Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-935149-66-8.

- Newton, Steven H. (2005). Hitler's Commander: Field Marshal Walther Model, Hitler's Favorite General. Da Capo Press Inc. ISBN 978-0306813993.

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1987). Moscow to Stalingrad. Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 9780880292948.

Russian sources

- Beshanov, Vladimir (2008). Year 1942 – 'Learning'. Eksmo, Yauza. ISBN 978-5699302680.

- Getman, Andrei (1973). Tanks go to Berlin. Military. publishing house of the Ministry of Defense of the USSR. ASIN B007WVFFNW.

- Isaev, Aleksey Valerevich (2006). Когда внезапности уже не было (When the element of surprise was lost). EKSMO, Jauza. ISBN 978-5699119493.

- SANDAL0V, L.M. (1960). Offensive operations of the 20th Army of the Western Front in August 1942. Military publishing house of the Ministry of Defense of the USSR.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

German sources

- Haupt, Werner (1983). Die Schlachten Die Mitte der Heeresgruppe. Aus der Sicht der Divisionen. Podzun-Pallas-Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3895555886.

- Stoves, Rolf (1961). 1. Panzer-Division 1935–1945. Podzun. ASIN B0000BOBMM.

- Strauss, Franz J (2005). Die Geschichte der 2. (Wiener) Panzer-Division. Dörfler Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3895552670.

- Selz, Barbara (1970). Das Grüne Regiment Der Weg der 256.Infanterie-Division aus der Sicht des Regimentes 481. Kehrer. ASIN B0000BUNXD.

- von Plato, Anton Detlev (1998). Geschichte der 5. Panzerdivision (1938 bis 1945). Walhalla und Praetoria Verlag Regensburg. ISBN 978-3927292208.

- Großmann, Horst (1987). Rshew, Eckpfeiler der Ostfront. Podzun-Pallas-Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3790901269.

- Conrady, Alexander. Rshew 1942/1943. ASIN B002HLXFZW.

External links

- German 10 day casualty reports listed by Army

- Articles about the Rzhez battles (Russian Text)

- The battle for hill 200

- Article On the 70th anniversary of the Pogorelov-Gorodyshchens'ka and Rzhev-Sychevsky operations in 1942. (Russian text)

- Journal of hostilities – 16th Guards Rifle Division – 07/30/42 to 08/22/42

Categories: