| Part of a series on | ||||

| Pollution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Air pollution from a paper mill near Munich Air pollution from a paper mill near Munich | ||||

| Air | ||||

| Biological | ||||

| Digital | ||||

| Electromagnetic | ||||

| Natural | ||||

| Noise | ||||

| Radiation | ||||

| Soil | ||||

| Solid waste | ||||

| Space | ||||

| Thermal | ||||

| Visual | ||||

| War | ||||

Water

|

||||

| Topics | ||||

Misc

|

||||

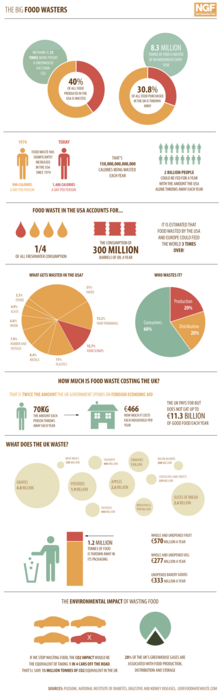

Food loss and waste is food that is not eaten. The causes of food waste or loss are numerous and occur throughout the food system, during production, processing, distribution, retail and food service sales, and consumption. Overall, about one-third of the world's food is thrown away. A similar amount is lost on top of that by feeding human-edible food to farm animals (the net effect wastes an estimated 1144 kcal/person/day). A 2021 meta-analysis, that did not include food lost during production, by the United Nations Environment Programme found that food waste was a challenge in all countries at all levels of economic development. The analysis estimated that global food waste was 931 million tonnes of food waste (about 121 kg per capita) across three sectors: 61 percent from households, 26 percent from food service and 13 percent from retail.

Food loss and waste is a major part of the impact of agriculture on climate change (it amounts to 3.3 billion tons of CO2e emissions annually) and other environmental issues, such as land use, water use and loss of biodiversity. Prevention of food waste is the highest priority, and when prevention is not possible, the food waste hierarchy ranks the food waste treatment options from preferred to least preferred based on their negative environmental impacts. Reuse pathways of surplus food intended for human consumption, such as food donation, is the next best strategy after prevention, followed by animal feed, recycling of nutrients and energy followed by the least preferred option, landfill, which is a major source of the greenhouse gas methane. Other considerations include unreclaimed phosphorus in food waste leading to further phosphate mining. Moreover, reducing food waste in all parts of the food system is an important part of reducing the environmental impact of agriculture, by reducing the total amount of water, land, and other resources used.

The UN's Sustainable Development Goal Target 12.3 seeks to "halve global per capita food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses" by 2030. Climate change mitigation strategies prominently feature reducing food waste. In the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference nations agree to reduce food waste by 50% by the year 2030.

Definition

Food loss and waste occurs at all stages of the food supply chain – production, processing, sales, and consumption. Definitions of what constitutes food loss versus food waste or what parts of foods (i.e., inedible parts) exit the food supply chain are considered lost or wasted vary. Terms are often defined on a situational basis (as is the case more generally with definitions of waste). Professional bodies, including international organizations, state governments, and secretariats may use their own definitions.

United Nations

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations defines food loss and waste as the decrease in quantity or quality of food along the food supply chain. Within this framework, UN Agencies distinguish loss and waste at two different stages in the process:

- Food loss occurs along the food supply chain from harvest/slaughter/catch up to, but not including, the sales level

- Food waste occurs at the retail and consumption level.

Important components of this definition include:

- Food redirected to nonfood chains (including animal feed, compost, or recovery to bioenergy) is not counted as food loss or waste. Inedible parts are not considered as food loss or waste (these inedible parts are sometimes referred to as unavoidable food waste)

Under Sustainable Development Goal 12, the Food and Agriculture Organization is responsible for measuring food loss, while the UN Environmental Program measures food waste.

The 2024 UNEP Food Waste Index Report, "Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste," addresses the severe issue of food waste that accounts for US$1 trillion in losses, 8–10% of global greenhouse emissions, and the unnecessary use of 30% of the world's agricultural land, exacerbating hunger and affecting child growth. In alignment with SDG 12.3, the report compiles 194 data points from 93 countries to illustrate the widespread nature of food waste, highlights the lack of disparity in waste levels across nations of varying income levels, and underscores the leadership roles of Japan and the UK among G20 nations in data tracking. It argues for a comprehensive definition of food waste, including both edible and inedible parts, and calls for improved data collection, particularly in retail and food service sectors of low-income countries, to enhance global efforts in halving food waste by 2030, with an upcoming focus on public-private partnerships as a key strategy.

European Union

In the European Union (EU), food waste is defined by combining the definitions of food and waste, namely: "any substance or product, whether processed, partially processed or unprocessed, intended to be, or reasonably expected to be ingested by humans (...)" (including things such as drinks and chewing gum; excluding things such as feed, medicine, cosmetics, tobacco products, and narcotic or psychotropic substances) "which the holder discards or intends or is required to discard".

Previously, food waste was defined by directive 75/442/EEC as "any food substance, raw or cooked, which is discarded, or intended or required to be discarded" in 1975. In 2006, 75/442/EEC was repealed by 2006/12/EC, which defined waste as "any substance or object in the categories set out in Annex I which the holder discards or intends or is required to discard". Meanwhile, Article 2 of Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002 (the General Food Law Regulation), as amended on 1 July 2022, defined food as "any substance or product, whether processed, partially processed or unprocessed, intended to be, or reasonably expected to be ingested by humans (...)", including things such as drinks and chewing gum, excluding things such as feed, medicine, cosmetics, tobacco products, and narcotic or psychotropic substances.

A 2016 European Court of Auditors special report had criticised the lack of a common definition of food waste as hampering progress, and a May 2017 resolution by the European Parliament supported a legally binding definition of food waste. Finally, the 2018/851/EU directive of 30 May 2018 (the revised Waste Framework Directive) combined the two (after waste was redefined in 2008 by Article 3.1 of 2008/98/EC as "any substance or object which the holder discards or intends or is required to discard") by defining food waste as "all food as defined in Article 2 of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council that has become waste."

United States

As of 2022, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) employed three categories:

- "Excess food refers to food that is recovered and donated to feed people."

- "Food waste refers to food such as plate waste (i.e., food that has been served but not eaten), spoiled food, or peels and rinds considered inedible that is sent to feed animals, to be composted or anaerobically digested, or to be landfilled or combusted with energy recovery."

- "Food loss refers to unused product from the agricultural sector, such as unharvested crops."

In 2006, the EPA defined food waste as "uneaten food and food preparation wastes from residences and commercial establishments such as grocery stores, restaurants, produce stands, institutional cafeterias and kitchens, and industrial sources like employee lunchrooms".

The states remain free to define food waste differently for their purposes, though as of 2009, many had not done so.

Other definitions

Bellemare et al. (2017) compared four definitions from:

- a Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) 2016 report: "Food loss is defined as 'the decrease in quantity or quality of food.' Food waste is part of food loss and refers to discarding or alternative (nonfood) use of food that is safe and nutritious for human consumption along the entire food supply chain, from primary production to end household consumer level";

- an Economic Research Service (ERS; a USDA agency) 2014 report: "Food loss represents the amount of food postharvest, that is available for human consumption but is not consumed for any reason. It includes cooking loss and natural shrinkage (for example, moisture loss); loss from mould, pests, or inadequate climate control; and food waste. Food waste is a component of food loss and occurs when an edible item goes unconsumed, as in food discarded by retailers due to color or appearance, and plate waste by consumers";

- a FUSIONS (an EU project) 2016 report: "Food waste is any food, and inedible parts of food, removed from the food supply chain to be recovered or disposed (including composed , crops ploughed in/not harvested, anaerobic digestion, bioenergy production, co-generation, incineration, disposal to sewer, landfill or discarded to sea)"; and

- an EPA 2016 report: "The amount of food going to landfills from residences, commercial establishments (e.g., grocery stores and restaurants), institutional sources (e.g., school cafeterias), and industrial sources (e.g., factory lunchrooms). Pre-consumer food generated during the manufacturing and packaging of food products is not included in EPA's food waste estimates."

According to Bellemare et al., the inclusion of food that goes to nonfood productive use is flawed for two reasons: "First, if recovered food is used as an input, such as animal feed, fertilizer, or biomass to produce output, then by definition it is not wasted. However, there might be economic losses if the cost of recovered food is higher than the average cost of inputs in the alternative, nonfood use. Second, the definition creates practical problems for measuring food waste because the measurement requires tracking food loss in every stage of the supply chain and its proportion that flows to nonfood uses." They argued that only food that ends up in landfills should be counted as food waste, pointing to the 2016 EPA definition as a good example. Bellemare et al. also noted that "the FAO and ERS definitions only apply to edible and safe and nutritious food, whereas the definitions of FUSIONS and the EPA apply to both edible and inedible parts of food. Finally, the ERS and EPA definitions of food waste exclude the food that is not harvested at the farm level."

A 2019 FAO report stated:

'The notion of food being lost or wasted is deceptively simple, but in practice there is no commonly agreed definition of food loss and waste. FAO has worked towards the harmonization of concepts related to food loss and waste, and the definitions adopted in this report are the result of a consensus reached in consultation with experts in this field. This report understands food loss and waste as the decrease in quantity or quality of food along the food supply chain. Empirically it considers food losses as occurring along the food supply chain from harvest/slaughter/catch up to, but not including, the retail level. Food waste, on the other hand, occurs at the retail and consumption level. This definition also aligns with the distinction implicit in SDG Target 12.3. This report also asserts that, although there may be an economic loss, food diverted to other economic uses, such as animal feed, is not considered as quantitative food loss or waste. Similarly, inedible parts are not considered as food loss or waste.'

Methodology

The 2019 FAO report stated: "Food loss and waste has typically been measured in physical terms using tonnes as reporting units. This measurement fails to account for the economic value of different commodities and can risk attributing a higher weight to low-value products just because they are heavier. report acknowledges this by adopting a measure that accounts for the economic value of produce." Hall et al. (2009) calculated food waste in the United States in terms of energy value "by comparing the US food supply data with the calculated food consumed by the US population." The result was that food waste among American consumers increased from "about 30% of the available food supply in 1974 to almost 40% in recent years" (the early 2000s), or about 900 kcal per person per day (1974) to about 1400 kcal per person per day (2003). A 2012 Natural Resources Defense Council report interpreted this to mean that Americans threw away up to 40% of food that was safe to eat. Buzby & Hyman (2012) estimated both the total weight (in kg and lbs) and monetary value (in USD) of food loss in the United States, concluding that "the annual value of food loss is almost 10% of the average amount spent on food per consumer in 2008".

Net Animal Losses

Net animal losses are the difference between the calories in human-edible crops fed to animals and the calories returned in meat, dairy and fish. These losses are higher than all conventional food losses combined. This is because livestock eat more human-edible food than their products provide. Research estimated that if the US would eat all human-edible food instead of feeding it to animals in order to eat their meat, dairy and eggs, it would free up enough food for an additional 350 million people. At a global level livestock is fed an average of 1738 kcal/person/day of human-edible food, and just 594 kcal/p/d of animal products return to the human food supply, a net loss of 66%.

Sources

Production

In the United States, food loss can occur at most stages of the food industry and in significant amounts. In subsistence agriculture, the amounts of food loss are unknown, but are likely to be insignificant by comparison, due to the limited stages at which loss can occur, and given that food is grown for projected need as opposed to a global marketplace demand. Nevertheless, on-farm losses in storage in developing countries, particularly in African countries, can be high although the exact nature of such losses is much debated.

In the food industry of the United States, the food supply of which is the most diverse and abundant of any country in the world, loss occurs from the beginning of food production chain. From planting, crops can be subjected to pest infestations and severe weather, which cause losses before harvest. Since natural forces (e.g. temperature and precipitation) remain the primary drivers of crop growth, losses from these can be experienced by all forms of outdoor agriculture. On average, farms in the United States lose up to six billion pounds of crops every year because of these unpredictable conditions. According to the IPCC sixth assessment report, encouraging the development of technologies that address issues in food harvesting and post-harvesting could have a significant impact on decreasing food waste in the supply chain early-on.

The use of machinery in harvesting can cause losses, as harvesters may be unable to discern between ripe and immature crops, or collect only part of a crop. Economic factors, such as regulations and standards for quality and appearance, also cause food waste; farmers often harvest selectively via field gleaning, preferring to not waste crops "not to standards" in the field (where they can still be used as fertilizer or animal feed), since they would otherwise be discarded later. This method of removing undesirable produce from harvest collection, distribution sites and grocery stores is called culling. However, usually when culling occurs at the production, food processing, retail and consumption stages, it is to remove or dispose of produce with a strange or imperfect appearance rather than produce that is spoiled or unsafe to eat. In urban areas, fruit and nut trees often go unharvested because people either do not realize that the fruit is edible or they fear that it is contaminated, despite research which shows that urban fruit is safe to consume.

Food processing

Food loss continues in the post-harvest stage, but the amounts of post-harvest loss involved are relatively unknown and difficult to estimate. Regardless, the variety of factors that contribute to food loss, both biological/environmental and socio-economical, would limit the usefulness and reliability of general figures. In storage, considerable quantitative losses can be attributed to pests and micro-organisms. This is a particular problem for countries that experience a combination of heat (around 30 °C) and ambient humidity (between 70 and 90 per cent), as such conditions encourage the reproduction of insect pests and micro-organisms. Losses in the nutritional value, caloric value and edibility of crops, by extremes of temperature, humidity or the action of micro-organisms, also account for food waste. Further losses are generated in the handling of food and by shrinkage in weight or volume.

Some of the food loss produced by processing can be difficult to reduce without affecting the quality of the finished product. Food safety regulations are able to claim foods that contradict standards before they reach markets. Although this can conflict with efforts to reuse food loss (such as in animal feed), safety regulations are in place to ensure the health of the consumer; they are vitally important, especially in the processing of foodstuffs of animal origin (e.g. meat and dairy products), as contaminated products from these sources can lead to and are associated with microbiological and chemical hazards.

Retail

Packaging protects food from damage during its transportation from farms and factories via warehouses to retailing, as well as preserving its freshness upon arrival. Although it avoids considerable food waste, packaging can compromise efforts to reduce food waste in other ways, such as by contaminating waste that could be used for animal feedstocks with plastics.

In 2013, the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) performed research that suggests that the leading cause of food waste in America is due to uncertainty over food expiration dates, such as confusion in deciphering best-before, sell-by, or use-by dates. Joined by Harvard's Food Law and Policy Clinic, the NRDC produced a study called The Dating Game: How Confusing Food Date Labels Leads to Food Waste in America. This United States-based study looked at the intertwining laws which lead labeling to end up unclear and erratic. This uncertainty leads to consumers to toss food, most often because they think the food may be unsafe or misunderstand the labeling on the food completely. Lack of regulation on labeling can result in large quantities of food being removed from the market overall.

Retail stores throw away large quantities of food. Usually, this consists of items that have reached either their best-before, sell-by, or use-by dates. Some stores make an effort to markdown these goods with systems like discount stickers, stores have widely varying policies to handle the above mentioned foods. Much of the food discarded by stores is still edible. Some stores put efforts into preventing access to poor or homeless people, while others work with charitable organization to distribute food. Retailers also contribute to waste as a result of their contractual arrangements with suppliers. Failure to supply agreed quantities renders farmers or processors liable to have their contracts cancelled. As a consequence, they plan to produce more than actually required to meet the contract, to have a margin of error. Surplus production is often simply disposed of.

Retailers usually have strict cosmetic standards for produce, and if fruits or vegetables are misshapen or superficially bruised, they are often not put on the shelf. In the United States, some of the estimated six billion pounds of produce wasted each year are discarded because of appearance. The USDA publishes guidelines used as a baseline assessment by produce distributors, grocery stores, restaurants and other consumers in order to rate the quality of food. These guidelines and how they rate are readily available on their website. For example, apples get graded by their size, color, wax residue, firmness, and skin appearance. If apples rank highly in these categories and show close to no superficial defects, they are rated as "U.S. Extra Fancy" or "U.S. Fancy", these are the typical ratings sought out by grocery stores when purchasing their produce. Any apples with suboptimal levels of appearance are ranked as either "U.S. Number 1" or "Utility" and are not normally purchased for retail, as recommended by produce marketing sources, despite being safe and edible. A number of regional programs and organizations have been established by the EPA and USDA in an attempt to reduce such produce waste. Organizations in other countries, such as Good & Fugly in Australia and No Food Waste in India, are making similar efforts worldwide. The popular trend of selling "imperfect" produce at retail has been criticized for overlooking existing markets for these foods (eg the food processing industry and bargain grocery stores) and downplaying the household-level wasting of food that is statistically a larger part of the overall problem.

The fishing industry wastes substantial amounts of food: about 40–60% of fish caught in Europe is discarded as the wrong size or wrong species.

This comes to about 2.3 million tonnes per annum in the North Atlantic and the North Sea.

Food-service industry

Addressing food waste requires involving multiple stakeholders throughout the food supply chain, which is a market-driven system. Each stakeholder and their food waste quantification can be dependent on geographical scales. This geographical scale then results in the production of different definitions of food waste, as mentioned earlier, with respect to the complexities of food supply chains and then create a narrative that further shows the needs for specific research on important stakeholders. The food service industry suggests to be a key stakeholder to achieve mitigation. The key players within the food service industry include the manufacturers, producers, farmers, managers, employees, and consumers. The key factors relating to food waste in restaurants include the food menu, the production procedure, the use of pre-prepared versus whole food products, dinnerware size, type of ingredients used, the dishes served, opening hours, and disposal methods. These factors then can be categorized in the different stages of operations that relate to pre-kitchen, kitchen-based, and post-kitchen processes.

In restaurants in developing countries, the lack of infrastructure and associated technical and managerial skills in food production have been identified as the key drivers in the creation of food waste currently and in the future. Comparatively, the majority of food waste in developed countries tends to be produced post-consumer, which is driven by the low prices of food, greater disposable income, consumers' high expectations of food cosmetic standards, and the increasing disconnect between consumers and how food is being produced (Urbanization). That being said, in United States restaurants alone, an estimated 22 to 33 billion pounds are wasted each year.

Serving plate size reduction has been identified as an intervention effective at reducing restaurant food waste. Under such interventions, restaurants decrease the size of plates for meals provided to diners. Similar interventions which have been found to be effective at reducing restaurant food waste include utilizing reusable rather than disposable plates and decreasing serving size.

Food and agricultural nonprofits

Food and agriculture nonprofits (FANOs) are an understudied player in food system sustainability and food waste management (). FANOs play an essential role at every step of the food supply chain () including in creating or preventing food waste ). Food waste can be defined as edible food discarded by consumers. In FANOs when food safety practices are not employed, it can lead to food waste (). Reducing food waste is a priority in many FANOs. Still, due to an absence of food safety processes being implemented and a lack of food safety regulations, food waste is prevalent and compounded. Well-intentioned nonprofit staff and volunteers work with insufficient knowledge of how to safely handle and store food to prevent spoilage. FANOs have limited resources, like volunteer time and sporadic donations, and may not have the capacity to decipher complex, contradictory food safety regulations. However, FANOs play a vital role in getting nutritious food to needy, hungry people and families, so these nonprofits are responsible for being good stewards of their food stores to prevent waste and protect their client's health by distributing safe food. Thus, despite limited resources, FANOs should focus on volunteer training. Furthermore, nonprofit and food scientists can play an essential role in supporting FANOs through joint volunteer training design and evaluation.

Consumption

Consumers are directly and indirectly responsible for wasting a lot of food, which could for a large part be avoided if they were willing to accept suboptimal food (SOF) that deviates in sensory characteristics (odd shapes, discolorations) or has a best-before date that is approaching or has passed, but is still perfectly fine to eat. In addition to inedible and edible food waste generated by consumers, substantial amounts of food is wasted through food overconsumption, also referred to as metabolic food waste, estimated globally as 10% of foods reaching the consumer. Several interventions have been designed to achieve food waste reduction at the consumer level, such as reducing portion size and changing plates. However, despite being practical to some extent, these interventions can result in unintended consequences due to the lack of understanding of underlying causes and what influences consumers to act on specific behaviors. Unintended consequences, for example, could be prioritizing unhealthy food at the expense of healthy food or reduced consumption and calorie intake in general.

By sector

Fruit and vegetables

This section is an excerpt from Post-harvest losses (vegetables).

Post-harvest losses of vegetables and fruits occur at all points in the value chain from production in the field to the food being placed on a plate for consumption. Post-harvest activities include harvesting, handling, storage, processing, packaging, transportation and marketing.

Losses of horticultural produce are a major problem in the post-harvest chain. They can be caused by a wide variety of factors, ranging from growing conditions to handling at retail level. Not only are losses clearly a waste of food, but they also represent a similar waste of human effort, farm inputs, livelihoods, investments, and scarce resources such as water. Post-harvest losses for horticultural produce are, however, difficult to measure. In some cases everything harvested by a farmer may end up being sold to consumers. In others, losses or waste may be considerable. Occasionally, losses may be 100%, for example when there is a price collapse and it would cost the farmer more to harvest and market the produce than to plough it back into the ground. Use of average loss figures is thus often misleading. There can be losses in quality, as measured both by the price obtained and the nutritional value, as well as in quantity.Grains

This section is an excerpt from Post-harvest losses (grains).

Grains may be lost in the pre-harvest, harvest, and post-harvest stages. Pre-harvest losses occur before the process of harvesting begins, and may be due to insects, weeds, and rusts. Harvest losses occur between the beginning and completion of harvesting, and are primarily caused by losses due to shattering. Post-harvest losses occur between harvest and the moment of human consumption. They include on-farm losses, such as when grain is threshed, winnowed, and dried. Other on-farm losses include inadequate harvesting time, climatic conditions, practices applied at harvest and handling, and challenges in marketing produce. Significant losses are caused by inadequate storage conditions as well as decisions made at earlier stages of the supply chain, including transportation, storage, and processing, which predispose products to a shorter shelf life.

Important in many developing countries, particularly in Africa, are on-farm losses during storage, when the grain is being stored for auto-consumption or while the farmer awaits a selling opportunity or a rise in prices.Fishing

In 2011, FAO estimated that up to 35 percent of global fisheries and aquaculture production is either lost or wasted every year.

Extent

Global extent

Efforts are underway by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to measure progress towards SDG Target 12.3 through two separate indices: the Food Loss Index (FLI) and the Food Waste Index (FWI).

According to FAO's The State of Food and Agriculture 2019, globally, in 2016, around 14 percent of the world's food is lost from production before reaching the retail level. Generally, levels of loss are higher for fruits and vegetables than for cereals and pulses. However, even for the latter, significant levels are found in sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, while they are limited in Central and Southern Asia.

Estimates from UN Environment's Food Waste Index suggest that about 931 million tonnes of food, or 17 percent of total food available to consumers in 2019, went into the waste bins of households, retailers, restaurants and other food services.

According to a report from Feedback EU, the EU wastes 153 million tonnes of food each year, around double previous estimates.

Earlier estimates

In 2011, an FAO publication based on studies carried out by The Swedish Institute for Food and Biotechnology (SIK) found that the total of global amount of food loss and waste was around one third of the edible parts of food produced for human consumption, amounting to about 1.3 billion tonnes (1.28×10 long tons; 1.43×10 short tons) per year. As the following table shows, industrialized and developing countries differ substantially. In developing countries, it is estimated that 400–500 calories per day per person are wasted, while in developed countries 1,500 calories per day per person are wasted. In the former, more than 40% of losses occur at the post-harvest and processing stages, while in the latter, more than 40% of losses occur at the retail and consumer levels. The total food waste by consumers in industrialized countries (222 million tonnes or 218,000,000 long tons or 245,000,000 short tons) is almost equal to the entire food production in sub-Saharan Africa (230 million tonnes or 226,000,000 long tons or 254,000,000 short tons).

| Region | Total | At the production and retail stages |

By consumers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 280 kg (617 lb) | 190 kg (419 lb) | 90 kg (198 lb) |

| North America and Oceania | 295 kg (650 lb) | 185 kg (408 lb) | 110 kg (243 lb) |

| Industrialized Asia | 240 kg (529 lb) | 160 kg (353 lb) | 80 kg (176 lb) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 160 kg (353 lb) | 155 kg (342 lb) | 5 kg (11 lb) |

| North Africa, West and Central Asia | 215 kg (474 lb) | 180 kg (397 lb) | 35 kg (77 lb) |

| South and Southeast Asia | 125 kg (276 lb) | 110 kg (243 lb) | 15 kg (33 lb) |

| Latin America | 225 kg (496 lb) | 200 kg (441 lb) | 25 kg (55 lb) |

A 2013 report from the British Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IME) likewise estimated that 30–50% (or 1.2–2 billion tonnes or 1.18×10–1.97×10 long tons or 1.32×10–2.20×10 short tons ) of all food produced remains uneaten.

Individual countries

Australia

Each year in New South Wales, more than 25 million meals are delivered by charity OzHarvest from food that would otherwise be wasted. Each year, the Australian economy loses $20 billion in food waste. This has a crucial environmental impact through the waste of resources used to produce, manufacture, package, and distribute that food.

In addition, it is estimated that 7.6 million tonnes of CO2 is generated by the disposed food in landfills. It is also the cause of odour, leaching, and potential generation for diseases. In March 2019, the Australian ministry of the environment shared the key findings of Australia's National food waste baseline, which will facilitate the tracking of the progress towards their goal to halve Australian food waste by 2030.

Many initiatives were taken by the Australian government in order to help achieve this goal. In fact, they financed $1.2 million in organization that invest in renewable energies systems to store and transport food. They also funded more than $10 million for research on food waste reduction. Local governments have also implemented programs such as information sessions on storing food and composting, diversion of waste from restaurants and cafes from landfills to shared recycling facilities and donation of food to organization that would otherwise be wasted.

Canada

In Canada, 58% of all food is wasted, amounting to 35.5 million tonnes of food per annuum. The value of this lost food is equivalent to CA$21 billion. Such quantities of food would be enough to feed all Canadians for five months. It is estimated that about one-third of this waste could be spared and sent to those in need. There are many factors that contribute to such large-scale waste. Manufacturing and processing food alone incur costs of CA$21 billion, or 4.82 million tons. Per household, it is estimated that $1,766 is lost in food loss and waste. The Government of Canada identifies three main factors contributing to household waste: (1) buying too much food and not eating it before it spoils, (2) malfunctioning or poorly-designed packaging that does not deter spoilage rates or contamination, and (3) improper disposing of food – using garbage bins instead of those intended for organic waste.

Canada, Mexico, and the United States are working together under the Commission for Environmental Cooperation in order to address the severe problem of food waste in North America.

Canada specifically is working in the following ways to reduce food waste:

- Canada pledged to consult on strategies in the Strategy on Short-lived Climate Pollutants to reduce avoidable food waste within the country. This will help to reduce methane emissions from Canadian landfills.

- The government has implemented a Food Policy for Canada Archived 2020-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, which is a movement towards a more sustainable food system.

- In February 2019, the government brought together several experts from different sectors to share ideas and discuss opportunities for measuring and reducing food loss and waste across the food supply chain.

During the 2022 Quebec general election, Québec solidaire party spokesman Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois stated that ending food waste in Quebec would be a priority of the party if they were in government. The party seeks to cut food waste by 50% by mandating large businesses and institutions to give unsold food to groups that would distribute the food, or to businesses that would process the food.

China

In 2015 the Chinese Academy of Sciences reported that in big cities there was 17 to 18 million tons of food waste, enough to feed over 30 million people. About 25% of the waste was staple foods and about 18% from meat.

In August 2020 the Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping said the amount of food waste was shocking and distressing. A local authority campaign "Operation empty plate" (Chinese: 光盘行动; pinyin: Guāngpán xíngdòng) was started to reduce waste, including encouraging food outlets to limit orders to one fewer main dish than the number of customers.

As of December 2020, a draft law is under consideration to penalise food outlets if they encourage or mislead customers to order excessive meals causing obvious waste, first with a warning and then fines of up to 10,000 yuan. It would allow restaurants to charge customers who leave excessive leftovers. Broadcasters-– radio, TV, or online – which produces publishes or disseminates the promotion of food waste, including overeating. who promote overeating or food waste could also be fined up to 100,000 yuan.

Denmark

According to Ministry of Environment (Denmark), over 700,000 tonnes per year of food is wasted every year in Denmark in the entire food value chain from farm to fork. Due to the work of activist Selina Juul's Stop Wasting Food movement, Denmark has achieved a national reduction in food waste by 25% in 5 years (2010–2015).

France

In France, approximately 1.3–1.9 million tonnes of food waste is produced every year, or between 20 and 30 kilograms per person per year. Out of the 10 million tonnes of food that is either lost or wasted in the country, 7.1 million tonnes of food wasted in the country, only 11% comes from supermarkets. Not only does this cost the French €16 billion per year, but also the negative impact on the environment is also shocking. In France, food waste emits 15.3 million tonnes of CO2, which represents 3% of the country's total CO2 emission. In response to this issue, in 2016, France became the first country in the world to pass a unanimous legislation that bans supermarkets from throwing away or destroying unsold food. Instead, supermarkets are expected to donate such food to charities and food banks. In addition to donating food, many businesses claim to prevent food waste by selling soon-to-be wasted products at discounted prices. The National Pact Against Food Waste in France has outlined eleven measures to achieve a food waste reduction by half by 2025.

Hungary

According to the research of the Hungarian national food waste prevention programme, Project Wasteless, hosted by the National Food Chain Safety Office, an average Hungarian consumer generated 68 kg food waste annually in 2016, and 49% of this amount could have been prevented (avoidable food waste). The research team replicated the study in 2019, According to the second measurement, food waste generated by the Hungarian households was estimated to be 65.5 kg per capita annually. Between the two periods, a 4% decrease was observed, despite significant economic expansion, likely due to the very intense media campaign of Project Wasteless. Covid-19 significantly affected the food waste behaviour of Hungarians: while the total food waste basically did not change, the edible (avoidable) and inedible (unavoidable) fractions show a particular transformation. Spending more time at home the discarded leftovers were reduced, resulting in a drop from 32 to 25 kg/capita/year in avoidable food waste, while home cooking became more prevalent, contributing to a significant rise in the amount of unavoidable food waste from 31 to 36 kg/capita/year. The last measurement in 2022 reports 59.9 kg/capita/year food waste production in the households, and the avoidable food waste part of it is 24 kg (40%). This indicates a reduction of 12% in total food waste and a reduction of 27% in avoidable food waste since the first measurement in 2016.

In 2021, The Hungarian Parliament passed a law dealing with food waste.

Italy

According to REDUCE project, which produced the first baseline dataset for Italy based on official EU methodological framework, food waste is 530 g per person per week at household stage (only edible fraction); food waste in school canteens corresponds to 586 g per pupil per week; retail food waste per capita, per year corresponds to 2.9 kg. See

Netherlands

According to Meeusen & Hagelaar (2008), between 30% and 50% of all food produced was estimated to be lost or thrown away at that time in the Netherlands, while a 2010 Agriculture Ministry (LNV) report stated that the Dutch population wasted 'at least 9.5m tonnes of food per year, worth at least €4.4bn.' In 2019, three studies into food waste in households in the Netherlands commissioned by the LNV were conducted, showing that the average household waste per capita had been reduced from 48 kilograms of "solid food (including dairy products, fats, sauces and soups)" in 2010, to 41.2 kilograms in 2016, to 34.3 kilograms in 2019. The waste of liquid foods (excluding beer and wine, first measured in 2019) that ended up in the sewer through sinks or toilets was analysed to have decreased from 57.3 litres per capita in 2010 to 45.5 litres in 2019.

New Zealand

This section is an excerpt from Food waste in New Zealand.Food waste in New Zealand is one of the many environmental issues that is being addressed by industry, individuals and government.

The total volume of food wasted in New Zealand is not known as food waste has not been investigated at all stages of the supply chain. However, research has been undertaken into household food waste, supermarket food waste and hospitality sector food waste. The Environment Select Committee held a briefing into foodwaste in 2018.Research done on household food waste in New Zealand found that larger households and households with more young people created more food waste. The average household in this case study put 40% of food waste into the rubbish.

Singapore

In Singapore, 788,600 tonnes (776,100 long tons; 869,300 short tons) of food was wasted in 2014. Of that, 101,400 tonnes (99,800 long tons; 111,800 short tons) were recycled. Since Singapore has limited agriculture ability, the country spent about S$14.8 billion (US$10.6 billion) on importing food in 2014. US$1.4 billion of it ends up being wasted, or 13 percent.

On January 1, 2020, Singapore implemented the Zero Waste Masterplan which aims to reduce Singapore's daily waste production by 30 percent. The project also aims to extend the lifespan of the Semaku Landfill, Singapore's only landfill, beyond 2025. As a direct result of the project, food waste dropped to 665,000 tonnes, showing a significant decrease from 2017's all-time high of 810,000 tonnes.

United Kingdom

This section is an excerpt from Food waste in the United Kingdom.

Food waste in the United Kingdom is a subject of environmental, and socioeconomic concern that has received widespread media coverage and been met with varying responses from government. Since 1915, food waste has been identified as a considerable problem and has been the subject of ongoing media attention, intensifying with the launch of the "Love Food, Hate Waste" campaign in 2007. Food waste has been discussed in newspaper articles, news reports and television programmes, which have increased awareness of it as a public issue. To tackle waste issues, encompassing food waste, the government-funded "Waste & Resources Action Programme" (WRAP) was created in 2000.

A significant proportion of food waste is produced by the domestic household, which in 2022, created 6.4 million tonnes of food waste (95kg or £250 per person); most of this was made up of salads and fresh vegetables. A majority of food waste food is avoidable, with the rest being divided almost equally into foods which are unavoidable (e.g. tea bags) and those that are unavoidable due to preference (e.g. bread crusts) or cooking type (e.g. potato skins).

Reducing the amount of food waste has been deemed critical if the UK is to meet international targets on climate change, limiting greenhouse gas emissions, and obligations under the European Landfill Directive to reduce biodegradable waste going to landfill. Equally great emphasis has been placed on the reduction of food waste, across all developed countries, as a means of ending the global food crisis that left millions worldwide starving and impoverished. In the context of the 2007–2008 world food price crisis, food waste was discussed at the 34th G8 summit in Hokkaidō, Japan. The then UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown said of the issue: "We must do more to deal with unnecessary demand, such as by all of us doing more to cut our food waste".

In June 2009, the Environment Secretary Hilary Benn announced the Government's "War on waste", a programme aimed at reducing Britain's food waste. The proposed plans under the scheme included: scrapping best before and limiting sell by labels on food, creating new food packaging sizes, constructing more "on-the-go" recycling points and unveiling five flagship anaerobic digestion plants. Two years after its launch, the "Love Food, Hate Waste" campaign was claiming it had already prevented 137,000 tonnes of waste and, through the help it had given to over 2,000,000 households, had made savings of £300,000,000.In the UK, it was stated in 2007 that 6,700,000 tonnes (6,590,000 long tons; 7,390,000 short tons) per year of wasted food (purchased and edible food which is discarded) amounted to a cost of £10.2 billion each year. This represented costs of £250 to £400 a year per household.

United States

According to United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), between 30–40 percent of food in the U.S. is wasted. Estimates of food waste in the United States range from 35 million tons to 103 million tons. In a study done by National Geographic in 2014, Elizabeth Royte indicated more than 30 percent of food in the United States, valued at $162 billion annually, is not eaten. The University of Arizona conducted a study in 2004 that indicated that 14% to 15% of United States edible food is untouched or unopened, amounting to $43 billion worth of discarded, but edible, food. In 2010, the United States Department of Agriculture came forth with estimations from the Economic Research Service that approximates food waste in the United States to be equivalent to 141 trillion calories.

USDA data from 2010 shows that 26% of fish, meat, and poultry were thrown away at the retail and consumer level. Since then, meat production has increased by more than 10%. Data scientist Harish Sethu says this means that billions of animals are raised and slaughtered only to end up in a landfill.

Impact on the environment

According to United Nations, about a third of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions is linked to food. Empirical evidence at the global level on the environmental footprints for major commodity groups suggests that, if the aim is to reduce land use, the primary focus should be on meat and animal products, which account for 60 percent of the land footprint associated with food loss and waste. If the aim is to target water scarcity, cereals and pulses make the largest contribution (more than 70 percent), followed by fruits and vegetables. In terms of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with food loss and waste, the biggest contribution is again from cereals and pulses (more than 60 percent), followed by roots, tubers and oil-bearing crops. However, the environmental footprint for different commodities also varies across regions and countries, due, among other things, to differences in crop yields and production techniques. According to the IPCC 6th Assessment Report, the reduction of food waste would be beneficial for improving availability of resources such as "water, land-use, energy consumption" and the overall reduction of greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere.

Prevention and valorisation

Limiting food wastage has seen the adoption of former World War I and World War II slogans by antiwaste groups such as WRAP.

Limiting food wastage has seen the adoption of former World War I and World War II slogans by antiwaste groups such as WRAP.

In 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference nations adopted an agreement for preserving biodiversity, including a commitment to reduce food waste by 50% by the year 2030.

According to FAO's The State of Food and Agriculture 2019, the case for reducing food loss and waste includes gains that society can reap but which individual actors may not take into account, namely: (i) increased productivity and economic growth; (ii) improved food security and nutrition; and (iii) mitigation of environmental impacts of losing and wasting food, in particular terms of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG emissions as well as lowering pressure on land and water resources. The last two societal gains, in particular, are typically seen as externalities of reducing food loss and waste.

Response to the problem of food waste at all social levels has varied hugely, including campaigns from advisory and environmental groups, and concentrated media attention on the subject.

As suggested by the food waste hierarchy, prevention and reuse pathways for human consumption have the highest priority levels for food waste treatment. The general approach to food waste reduction comprise two main pathways: prevention and valorisation. Prevention of food waste infers all actions that reduce food production and ultimately prevent food from being produced in vain, such as food donations or re-processing into new food products. Valorisation on the other hand comprise actions that recover the materials, nutrients or energy in food waste, for instance by producing animal feed, fuel or energy from the "wastes" making it as potential resource.

Multiple studies have studied the environmental benefits of food waste prevention measures, including food donations, recovery of unharvested vegetables for re-use in food production, re-processing of surplus bread for beer production, and producing chutney or juice from leftovers. Food waste can also be used to produce multiple high-value products, such as a fish oil substitute for food or feed use via marine micro algae, without compromising the ability to produce energy via biogas. The general consensus currently suggest that reducing food waste by either prevention or valorisation, for human consumption, infers higher environmental benefits compared to the lower priority levels, such as energy production or disposal.

Multiple private enterprises have developed hardware and software solutions dealing mainly with the prevention of food waste within foodservice production facilities (contract catering, hotels & resorts, cruise ships, casinos etc.), by gathering quantitative and qualitative data about the specific food waste, helping chefs and managers reduce food waste by up to 70% by improving and optimizing their workflows and menus.

Food rescue

Main article: food rescueThere are multiple initiatives that rescue food that would otherwise not be consumed by humans anymore. The food can come from supermarkets, restaurants or private households for example. Such initiatives are:

- food banks,

- online platforms like Too Good To Go and Olio,

- public foodsharing shelves like those from foodsharing.de and

- dumpster diving.

Consumer marketing

One way of dealing with food waste is to reduce its creation. Consumers can reduce spoilage by planning their food shopping, avoiding potentially wasteful spontaneous purchases, and storing foods properly (and also preventing a too large buildup of perishable stock). Widespread educational campaigns have been shown to be an effective way to reduce food waste.

A British campaign called "Love Food, Hate Waste" has raised awareness about preventative measures to address food waste for consumers. Through advertisements, information on food storage and preparation and in-store education, the UK observed a 21% decrease in avoidable household food waste over the course of 5 years.

Another potential solution is for "smart packaging" which would indicate when food is spoiled more precisely than expiration dates currently do, for example with temperature-sensitive ink, plastic that changes color when exposed to oxygen, or gels that change color with time.

An initiative in Curitiba, Brazil, called Cambio Verde allows farmers to provide surplus produce (produce they would otherwise discard due to too low prices) to people that bring glass and metal to recycling facilities (to encourage further waste reduction). In Europe, the Food Surplus Entrepreneurs Network (FSE Network), coordinates a network of social businesses and nonprofit initiatives with the goal to spread best practices to increase the use of surplus food and reduction of food waste.

An overarching consensus exists on the substantial environmental benefits of food waste reduction. However, rebound effects may cause substitutive consumption as a result of economic savings made from food waste prevention, potentially offsetting more than half of the avoided emissions (depending on the type of food and price elasticities involved).

Collection

In areas where the waste collection is a public function, food waste is usually managed by the same governmental organization as other waste collection. Most food waste is combined with general waste at the source. Separate collections, also known as source-separated organics, have the advantage that food waste can be disposed of in ways not applicable to other wastes. In the United States, companies find higher and better uses for large commercial generators of food and beverage waste.

From the end of the 19th century through the middle of the 20th century, many municipalities collected food waste (called "garbage" as opposed to "trash") separately. This was typically disinfected by steaming and fed to pigs, either on private farms or in municipal piggeries.

Separate curbside collection of food wastes is now being revived in some areas. To keep collection costs down and raise the rate of food waste segregation, some local authorities, especially in Europe, have introduced "alternate weekly collections" of biodegradable waste (including, e.g., garden waste), which enable a wider range of recyclable materials to be collected at reasonable cost, and improve their collection rates. However, they result in a two-week wait before the waste will be collected. The criticism is that particularly during hot weather, food waste rots and stinks, and attracts vermin. Waste container design is therefore essential to making such operations feasible. Curbside collection of food waste is also done in the U.S., some ways by combining food scraps and yard waste together. Several states in the U.S. have introduced a yard waste ban, not accepting leaves, brush, trimmings, etc. in landfills. Collection of food scraps and yard waste combined is then recycled and composted for reuse.

Disposal

As alternatives to landfill, food waste can be composted to produce soil and fertilizer, fed to animals or insects, or used to produce energy or fuel. Some wasted fruit parts, can also be biorefined to extract useful substances for the industry (i.e. succinic acid from orange peels, lycopene from tomato peels).

Landfills and greenhouse gases

Main article: landfill gasDumping food waste in a landfill causes odour as it decomposes, attracts flies and vermin, and has the potential to add biological oxygen demand (BOD) to the leachate. The European Union Landfill Directive and Waste Regulations, like regulations in other countries, enjoin diverting organic wastes away from landfill disposal for these reasons. Starting in 2015, organic waste from New York City restaurants will be banned from landfills.

In countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, food scraps constitute around 19% of the waste buried in landfills, where it biodegrades very easily and produces methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

Methane, or CH4, is the second most prevalent greenhouse gas that is released into the air, also produced by landfills in the U.S. Although methane spends less time in the atmosphere (12 years) than CO2, it is more efficient at trapping radiation. It is 25 times greater to impact climate change than CO2 in a 100-year period. Humans accounts over 60% of methane emissions globally.

Fodder and insect feed

Large quantities of fish, meat, dairy and grain are discarded at a global scale annually, when they can be used for things other than human consumption. The feeding of food scraps or slop to domesticated animals such as pigs or chickens is, historically, the most common way of dealing with household food waste. The animals turn roughly two thirds of their ingested food into gas or fecal waste, while the last third is digested and repurposed as meat or dairy products. There are also different ways of growing produce and feeding livestock that could ultimately reduce waste.

Bread and other cereal products discarded from the human food chain could be used to feed chickens. Chickens have traditionally been given mixtures of waste grains and milling by-products in a mixture called chicken scratch. As well, giving table scraps to backyard chickens is a large part of that movement's claim to sustainability, though not all backyard chicken growers recommend it. Ruminants and pigs have also been fed bakery waste for a long time.

Certain food waste (such as flesh) can also be used as feed in maggot farming. The maggots can then be fed to other animals. In China, some food waste is being processed by feeding it to cockroaches.

Composting

Main article: Compost

Food waste can be biodegraded by composting, and reused to fertilize soil. Composting is the aerobic process completed by microorganisms in which the bacteria break down the food waste into simpler organic materials that can then be used in soil. By redistributing nutrients and high microbial populations, compost reduces water runoff and soil erosion by enhancing rainfall penetration, which has been shown to reduce the loss of sediment, nutrients, and pesticide losses to streams by 75–95%.

Composting food waste leads to a decrease in the quantity of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. In landfills, organic food waste decomposes anaerobically, producing methane gas that is emitted into the atmosphere. When this biodegradable waste is composted, it decomposes aerobically and does not produce methane, but instead produces organic compost that can then be utilized in agriculture. Recently, the city of New York has begun to require that restaurants and food-producing companies begin to compost their leftover food. Another instance of composting progress is a Wisconsin-based company called WasteCap, who is dedicated towards aiding local communities create composting plans.

Municipal Food Waste (MFW) can be composted to create this product of organic fertilizer, and many municipalities choose to do this citing environmental protection and economic efficiency as reasoning. Transporting and dumping waste in landfills requires both money and room in the landfills that have very limited available space. One municipality who chose to regulate MFW is San Francisco, who requires citizens to separate compost from trash on their own, instituting fines for non-compliance at $100 for individual homes and $500 for businesses. The city's economic reasoning for this controversial mandate is supported by their estimate that one business can save up to $30,000 annually on garbage disposal costs with the implementation of the required composting.

Home composting

Composting is an economical and environmentally conscious step many homeowners could take to reduce their impact on landfill waste. Instead of food scraps and spoiled food taking up space in trashcans or stinking up the kitchen before the bag is full, it could be put outside and broken down by worms and added to garden beds.

There also exists an opportunity for increased home composting via social contagion, where people in a network can learn new behaviors such as home composting, and the new behavior can spread spontaneously through the group. If enough people are influenced, the community can reach a tipping point, in which a majority of people transition to a new habit; a 2018 study published in Nature claims that with only 25 per cent of a population, a minority perspective was able to overturn the majority.

Anaerobic digestion

Main article: anaerobic digestionAnaerobic digestion produces both useful gaseous products and a solid fibrous "compostable" material. Anaerobic digestion plants can provide energy from waste by burning the methane created from food and other organic wastes to generate electricity, defraying the plants' costs and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The United States Environmental Protection Agency states that the use of anaerobic composting allows for large amounts of food waste to avoid the landfills. Instead of producing these greenhouse gasses into the environment from being in a landfill, the gasses can alternatively be harnessed in these facilities for reuse.

Since this process of composting produces high volumes of biogas, there are potential safety issues such as explosion and poisoning. These interactions require proper maintenance and personal protective equipment is utilized. Certain U.S. states, such as Oregon, have implemented the requirement for permits on such facilities, based on the potential danger to the population and surrounding environment.

Food waste coming through the sanitary sewers from garbage disposal units is treated along with other sewage and contributes to sludge.

Commercial liquid food waste

See also: Vegetable oil recyclingCommercially, food waste in the form of wastewater coming from commercial kitchens' sinks, dishwashers and floor drains is collected in holding tanks called grease interceptors to minimize flow to the sewer system. This often foul-smelling waste contains both organic and inorganic waste (chemical cleaners, etc.) and may also contain hazardous hydrogen sulfide gases. It is referred to as fats, oils, and grease (FOG) waste or more commonly "brown grease" (versus "yellow grease", which is fryer oil that is easily collected and processed into biodiesel) and is an overwhelming problem, especially in the US, for the aging sewer systems. Per the US EPA, sanitary sewer overflows also occur due to the improper discharge of FOGs to the collection system. Overflows discharge 3–10 billion U.S. gallons (11–38 million cubic meters) of untreated wastewater annually into local waterways, and up to 5,500 illnesses annually are due to exposure to contamination from sanitary sewer overflows into recreational waters.

See also

- Anaerobic digestion

- Gleaning

- List of waste types

- Post-harvest losses (grains)

- Post-harvest losses (vegetables)

- Source Separated Organics

- Waste & Resources Action Programme

- Waste management

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, In brief, 24, FAO, FAO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, In brief, 24, FAO, FAO.

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024, FAO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024, FAO.

References

- Greenfield, Robin (October 6, 2014). "The Food Waste Fiasco: You Have to See it to Believe it!". www.robingreenfield.org.

- Jenny Gustavsson. Global food losses and food waste : extent, causes and prevention : study conducted for the International Congress "Save Food!" at Interpack 2011 Düsseldorf, Germany. OCLC 1126211917.

- "UN Calls for Action to End Food Waste Culture". Daily News Brief. October 4, 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-10-04. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ^ UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021 (Report). United Nations Environment Programme. March 4, 2021. ISBN 9789280738513. Archived from the original on 2022-02-01. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- "FAO - News Article: Food wastage: Key facts and figures". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-07. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- "A third of food is wasted, making it third-biggest carbon emitter, U.N. says". Reuters. September 11, 2013. Archived from the original on 2021-06-07. Retrieved 2021-06-07.

- "Brief on food waste in the European Union". European Commission. August 25, 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-11-15. Retrieved 2022-11-15.

- "Food Recovery Hierarchy". www.epa.gov. August 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 2019-05-23. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313 Archived 2020-10-23 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Reduced Food Waste". Project Drawdown. February 12, 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-09-24. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- ^ "COP15: Nations Adopt Four Goals, 23 Targets for 2030 in Landmark UN Biodiversity Agreement". Convention on Biological Diversity. United Nations. Archived from the original on 2022-12-20. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ FAO (2019). In brief: The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. Rome. Archived from the original on 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bellemare, Marc F.; Çakir, Metin; Peterson, Hikaru Hanawa; Novak, Lindsey; Rudi, Jeta (2017). "On the Measurement of Food Waste". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 99 (5): 1148–1158. doi:10.1093/ajae/aax034.

- Westendorf, Michael L. (2000). Food waste to animal feed. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-8138-2540-3. Archived from the original on 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ Oreopoulou, Vasso; Winfried Russ (2007). Utilization of by-products and treatment of waste in the food industry. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-33511-7. Archived from the original on 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- "Definition of food loss and waste". ThinkEatSave. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- "Food Waste Index". ThinkEatSave. Archived from the original on 2022-02-02. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- Environment, U. N. (March 21, 2024). "Food Waste Index Report 2024". UNEP - UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 2024-04-11.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2024). Food Waste Index Report 2024. Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/45230.

- ^ Tarja Laaninen & Maria Paola Calasso (December 2020). "Reducing food waste in the European Union" (PDF). europarl.europa.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-07. Retrieved 2022-08-05.

- ^ Consolidated text: Directive 2006/12/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2006 on waste. No longer in force, Date of end of validity: 11/12/2010; Repealed by 32008L0098.

- Consolidated text: Council Directive of 15 July 1975 on waste (75/442/EEC). No longer in force, Date of end of validity: 16/05/2006; Repealed by 32006L0012.

- ^ Consolidated text: Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives

- Consolidated text: Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety

- Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste

- "Sustainable Management of Food Basics | US EPA". United States Environmental Protection Agency. August 11, 2015. Archived from the original on 2022-08-05. Retrieved 2022-08-05.

- "Excess food refers to food that is recovered and donated to feed people. Food waste refers to food such as plate waste (i.e., food that has been served but not eaten), spoiled food, or peels and rinds considered inedible that is sent to feed animals, to be composted or anaerobically digested, or to be landfilled or combusted with energy recovery. Food loss refers to unused product from the agricultural sector, such as unharvested crops."

- "Terms of Environment: Glossary, Abbreviations and Acronyms (Glossary F)". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2006. Archived from the original on 2003-02-19. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- "Organic Materials Management Glossary". California Integrated Waste Management Board. 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-12-07. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- "Chapter 3.1. Compostable Materials Handling Operations and Facilities Regulatory Requirements". California Integrated Waste Management Board. Archived from the original on 2009-10-09. Retrieved 2009-08-25.

- "Food Material" means any material that was acquired for animal or human consumption, is separated from the municipal solid waste stream, and that does not meet the definition of "agricultural material."

- "Food Waste Composting Regulations" (PDF). California Integrated Waste Management Board. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-10. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- "Many states surveyed for this paper do not define food waste or distinguish between pre-consumer and post consumer food waste, while other states classify food waste types."

- Hall, K. D.; Guo, J.; Dore, M.; Chow, C. C. (November 2009). "The Progressive Increase of Food Waste in America and Its Environmental Impact". PLOS ONE. 4 (11): e7940. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7940H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007940. PMC 2775916. PMID 19946359.

- Gunders, Dana (August 2012). "Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Far to Fork to Landfill" (PDF). nrdc.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-06-17. Retrieved 2017-06-20.

- Buzby, Jean C.; Hyman, Jeffrey (October 2012). "Total and per capita value of food loss in the United States". Food Policy. 37 (5): 561–570. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.06.002. Archived from the original on 2022-08-05. Retrieved 2022-08-05.

- "Food waste: The biggest loss could be what you choose to put in your mouth". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- Shepon, Alon; Eshel, Gidon; Noor, Elad; Milo, Ron (April 10, 2018). "The opportunity cost of animal based diets exceeds all food losses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (15): 3804–3809. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.3804S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1713820115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5899434. PMID 29581251.

- Berners-Lee, M.; Kennelly, C.; Watson, R.; Hewitt, C. N. (2018). "Current global food production is sufficient to meet human nutritional needs in 2050 provided there is radical societal adaptation". Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene. 6: 52. Bibcode:2018EleSA...6...52B. doi:10.1525/elementa.310.

- ^ Kantor, Linda Scott; Lipton, Kathryn; Manchester, Alden; Oliveira, Victor (January–April 1997). "Estimating and Addressing America's Food Losses" (PDF). Food Review (USDA): 2–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-03.

- Waters, Tony (2007). The Persistence of Subsistence Agriculture: life beneath the level of the marketplace. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0768-3. Archived from the original on 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- "Food Security". Scientific Alliance. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- "... there is certainly a lot of waste in the system ... Unless, that is, we were to go back to subsistence agriculture …"

- Shepherd A.W. (1991). "A Market-Oriented Approach to Post-harvest Management" (PDF). Rome: FAO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-29. Retrieved 2017-04-23.

- Savary, Serge; Willocquet, Laetitia; Elazegui, Francisco A; Castilla, Nancy P; Teng, Paul S (2000). "Rice Pest Constraints in Tropical Asia: Quantification of Yield Losses Due to Rice Pests in a Range of Production Situations". Plant Disease. 84 (3): 357–69. doi:10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.3.357. PMID 30841254.

- Rosenzweig, Cynthia; Iglesias, Ana; Yang, X.B; Epstein, Paul R; Chivian, Eric (2001). "Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events; Implications for Food Production, Plant Diseases, and Pests". Global Change and Human Health. 2 (2): 90–104. doi:10.1023/A:1015086831467. hdl:2286/R.I.55344. S2CID 44855998.

- Haile, Menghestab (2005). "Weather patterns, food security and humanitarian response in sub-Saharan Africa". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 360 (1463): 2169–82. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1746. PMC 1569582. PMID 16433102.

- "Food Waste". GRACE Communications Foundation. Archived from the original on 2018-03-07. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- "Climate change mitigation". OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Finland 2021. February 1, 2022. doi:10.1787/6a520df3-en. ISBN 978-92-64-84599-2. S2CID 131646210.

- "Wonky fruit & vegetables make a comeback!". European Parliament. 2009. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- Goldenberg, Suzanna (July 13, 2016). "Half of all US food produce is thrown away, new research suggests". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ^ Gustavson, Jenny; Cederberg, Christel; Sonesson, Ulf; van Otterdijk, Robert; Meybeck, Alexandre (2011). Global Food Losses and Food Waste (PDF). FAO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-01-28. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- "Is it safe to eat apples picked off city trees?". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ Morris, Robert F.; United States National Research Council (1978). Postharvest food losses in developing countries. National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- Kumar, Deepak; Kalita, Prasanta (January 15, 2017). "Reducing Postharvest Losses during Storage of Grain Crops to Strengthen Food Security in Developing Countries". Foods. 6 (1): 8. doi:10.3390/foods6010008. ISSN 2304-8158. PMC 5296677. PMID 28231087.

- "Agricultural engineering in development - Post-harvest losses". www.fao.org. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "Loss and waste: Do we really know what is involved?". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 2009-11-09. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- Lacey, J (1989). "Pre- and post-harvest ecology of fungi causing spoilage of foods and other stored products". Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 67 (s18): 11s – 25s. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb03766.x. PMID 2508232.

- "Post-harvest system and food losses". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 2009-11-08. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- Dalzell, Janet M. (2000). Food industry and the environment in the European Union: practical issues and cost implications. Springer. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-8342-1719-5. Archived from the original on 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- "Environmental, Health and Safety Guidelines for Meat Processing" (PDF). International Finance Corporation. April 30, 2007. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- "Specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin". Europa. 2009. Archived from the original on 2015-04-06. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- "Foodstuffs of animal origin … may present microbiological and chemical hazards"

- ^ "Making the most of packaging, A strategy for a low-carbon economy" (PDF). Defra. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-01-08. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- Robertson, Gordon L. (2006). Food packaging: principles and practice. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-3775-8. Archived from the original on 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- "Review of Food Waste Depackaging Equipment" (PDF). Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP). 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-07. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ "New Report: Food Expiration Date Confusion Causing up to 90% of Americans to Waste Food". NRDC. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-30.

- Greenaway, Twilight (June 26, 2016). "Can Walmart's food labels make a dent in America's $29bn food waste problem?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2017-11-30. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- Sacks, Stefanie (2014). What the Fork Are You Eating?: An Action Plan for Your Pantry and Plate. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 155. ISBN 9780399167966. Archived from the original on 2023-03-02. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ *Stuart, Tristram (2009). Waste: Uncovering the Global Food Scandal: The True Cost of What the Global Food Industry Throws Away. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-103634-2.

- "6 Billion Pounds Of Perfectly Edible Produce Is Wasted Every Year Because It's Ugly". The Huffington Post. May 19, 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- "USDA Grades and Standards". USDA. Archived from the original on 2015-08-05.

- ^ "Apple Grades and Standards". Archived from the original on 2015-09-05.

- "Fruit Product Sheet" (PDF). Produce Marketing Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-30.

- "Food Waste Activities". Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- "Wasted Food Programs and Resources Across the United States". May 23, 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- "Plans for imperfect fruit and vegetables". Farm Weekly. April 2, 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- "India has a food wastage problem. Here's how individuals can make a difference". April 7, 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- "Farms Aren't Tossing Perfectly Good Produce. You Are". The Washington Post. March 8, 2019. Archived from the original on 2022-05-28. Retrieved 2022-09-18.