Forensic anthropology is the application of the anatomical science of anthropology and its various subfields, including forensic archaeology and forensic taphonomy, in a legal setting. A forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification of deceased individuals whose remains are decomposed, burned, mutilated or otherwise unrecognizable, as might happen in a plane crash. Forensic anthropologists are also instrumental in the investigation and documentation of genocide and mass graves. Along with forensic pathologists, forensic dentists, and homicide investigators, forensic anthropologists commonly testify in court as expert witnesses. Using physical markers present on a skeleton, a forensic anthropologist can potentially determine a person's age, sex, stature, and race. In addition to identifying physical characteristics of the individual, forensic anthropologists can use skeletal abnormalities to potentially determine cause of death, past trauma such as broken bones or medical procedures, as well as diseases such as bone cancer.

The methods used to identify a person from a skeleton relies on the past contributions of various anthropologists and the study of human skeletal differences. Through the collection of thousands of specimens and the analysis of differences within a population, estimations can be made based on physical characteristics. Through these, a set of remains can potentially be identified. The field of forensic anthropology grew during the twentieth century into a fully recognized forensic specialty involving trained anthropologists as well as numerous research institutions gathering data on decomposition and the effects it can have on the skeleton.

Modern uses

Today, forensic anthropology is a well-established discipline within the forensic field. Anthropologists are called upon to investigate remains and to help identify individuals from bones when other physical characteristics that could be used to identify a body no longer exist. Forensic anthropologists work in conjunction with forensic pathologists to identify remains based on their skeletal characteristics. If the victim is not found for a lengthy period or has been eaten by scavengers, flesh markers used for identification would be destroyed, making normal identification difficult if not impossible. Forensic anthropologists can provide physical characteristics of the person to input into missing person databases such as that of the National Crime Information Center in the US or INTERPOL's yellow notice database.

In addition to these duties, forensic anthropologists often assist in the investigation of war crimes and mass fatality investigations. Anthropologists have been tasked with helping to identify victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, as well as plane crashes such as the Arrow Air Flight 1285 disaster and the USAir Flight 427 disaster where the flesh had been vaporized or so badly mangled that normal identification was impossible. Anthropologists have also helped identify victims of genocide in countries around the world, often long after the actual event. War crimes anthropologists have helped investigate include the Rwandan genocide and the Srebrenica Genocide. Organizations such as the Forensic Anthropology Society of Europe, the British Association for Forensic Anthropology, and the American Society of Forensic Anthropologists continue to provide guidelines for the improvement of forensic anthropology and the development of standards within the discipline.

With hundreds missing and bodies burnt beyond recognition by Hamas militants during its October 7 attack of Israel, Israeli authorities assembled recovery teams that included archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Authority. The team used their specialized skills in excavating and identifying fragmentary ancient remains to sift through ash and rubble for bone fragments overlooked by other forensic teams. Archeologists systematically searched rooms, dividing them into grids and carefully extracting bone shards. At one house, the archeology team found a bloodstain under ash that they determined was the outline of a body, later identified through DNA analysis.

History

Early history

The use of anthropology in the forensic investigation of remains grew out of the recognition of anthropology as a distinct scientific discipline and the growth of physical anthropology. The field of anthropology began in the United States and struggled to obtain recognition as a legitimate science during the early years of the twentieth century. Earnest Hooton pioneered the field of physical anthropology and became the first physical anthropologist to hold a full-time teaching position in the United States. He was an organizing committee member of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists along with its founder Aleš Hrdlička. Hooton's students created some of the first doctoral programs in physical anthropology during the early 20th century. In addition to physical anthropology, Hooton was a proponent of criminal anthropology. Now considered a pseudoscience, criminal anthropologists believed that phrenology and physiognomy could link a person's behavior to specific physical characteristics. The use of criminal anthropology to try to explain certain criminal behaviors arose out of the eugenics movement, popular at the time. It is because of these ideas that skeletal differences were measured in earnest eventually leading to the development of anthropometry and the Bertillon method of skeletal measurement by Alphonse Bertillon. The study of this information helped shape anthropologists' understanding of the human skeleton and the multiple skeletal differences that can occur.

Another prominent early anthropologist, Thomas Wingate Todd, was primarily responsible for the creation of the first large collection of human skeletons in 1912. In total, Todd acquired 3,300 human skulls and skeletons, 600 anthropoid skulls and skeletons, and 3,000 mammalian skulls and skeletons. Todd's contributions to the field of anthropology remain in use in the modern era and include various studies regarding suture closures on the skull and timing of teeth eruption in the mandible. Todd also developed age estimates based on physical characteristics of the pubic symphysis. Though the standards have been updated, these estimates are still used by forensic anthropologists to narrow down an age range of skeletonized remains. These early pioneers legitimized the field of anthropology, but it was not until the 1940s, with the help of Todd's student, Wilton M. Krogman, that forensic anthropology gained recognition as a legitimate subdiscipline.

The growth of forensic anthropology

During the 1940s, Krogman was the first anthropologist to actively publicize anthropologists' potential forensic value, going as far as placing advertisements in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin informing agencies of the ability of anthropologists to assist in the identification of skeletal remains. This period saw the first official use of anthropologists by federal agencies including the FBI. During the 1950s, the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps employed forensic anthropologists in the identification of war casualties during the Korean War. It was at this time that forensic anthropology officially began. The sudden influx of available skeletons for anthropologists to study, whose identities were eventually confirmed, allowed for the creation of more accurate formulas for the identification of sex, age, and stature based solely on skeletal characteristics. These formulas, developed in the 1940s and refined by war, are still in use by modern forensic anthropologists.

The professionalization of the field began soon after, during the 1950s and 1960s. This move coincided with the replacement of coroners with medical examiners in many locations around the country. It was during this time that the field of forensic anthropology gained recognition as a separate field within the American Academy of Forensic Sciences and the first forensic anthropology research facility and body farm was opened by William M. Bass. Public attention and interest in forensic anthropology began to increase around this time as forensic anthropologists started working on more high-profile cases. One of the major cases of the era involved anthropologist Charles Merbs who helped identify the victims murdered by Ed Gein.

Methods

One of the main tools forensic anthropologists use in the identification of remains is their knowledge of osteology and the differences that occur within the human skeleton. During an investigation, anthropologists are often tasked with helping to determinate an individual's sex, stature, age, and ancestry. To do this, anthropologists must be aware of how the human skeleton can differ between individuals.

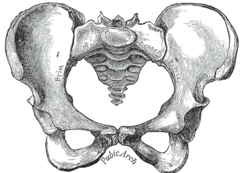

Determination of sex

Depending on which bones are present, sex can be determined by looking for distinctive sexual dimorphisms. When available, the pelvis is extremely useful in the determination of sex and when properly examined can achieve sex determination with a great level of accuracy. The examination of the pubic arch and the location of the sacrum can help determine sex.

Female pelvis. Note wide pubic arch and shorter, pushed back sacrum

Female pelvis. Note wide pubic arch and shorter, pushed back sacrum Male pelvis. Note narrow pubic arch and longer sacrum.

Male pelvis. Note narrow pubic arch and longer sacrum.

However, the pelvis is not always present, so forensic anthropologists must be aware of other areas on the skeleton that have distinct characteristics between sexes. The skull also contains multiple markers that can be used to determine sex. Specific markers on the skull include the temporal line, the eye sockets, the supraorbital ridge, as well as the nuchal lines, and the mastoid process. In general, male skulls tend to be larger and thicker than female skulls, and to have more pronounced ridges.

Forensic anthropologists need to take into account all available markers in the determination of sex due to the differences that can occur between individuals of the same sex. For example, a female may have a slightly more narrow than a normal pubic arch. It is for this reason that anthropologists usually classify sex as one of five possibilities: male, maybe male, indeterminate, maybe female, or female. In addition, forensic anthropologists are generally unable to make a sex determination unless the individual was an adult at the time of death. The sexual dimorphisms present in the skeleton begin to occur during puberty and are not fully pronounced until after sexual maturation.

Consequently, there is currently no reliable method of sex determination of juvenile remains from cranial or post-cranial skeletal elements since dimorphic traits only become apparent after puberty, and this represents a fundamental problem in archaeological and forensic investigations. However, teeth may assist in estimating sex since both sets of teeth are formed well before puberty. Sexual dimorphism has been observed in both deciduous and permanent dentition, although it is much less in deciduous teeth. On average, male teeth are slightly larger than female teeth, with the greatest difference observed in the canine teeth. Examination of internal dental tissues has also shown that male teeth consist of absolutely and proportionately greater quantities of dentine than females. Such differences in dental tissue proportions could also be useful in sex determination.

Determination of stature

The estimation of stature by anthropologists is based on a series of formulas that have been developed over time by the examination of multiple different skeletons from a multitude of different regions and backgrounds. Stature is given as a range of possible values, in centimeters, and typically computed by measuring the bones of the leg. The three bones that are used are the femur, the tibia, and the fibula. In addition to the leg bones, the bones of the arm, humerus, ulna, and radius can be used. The formulas that are used to determine stature rely on various information regarding the individual. Sex, ancestry, and age should be determined before attempting to ascertain height, if possible. This is due to the differences that occur between populations, sexes, and age groups. By knowing all the variables associated with height, a more accurate estimate can be made. For example, a male formula for stature estimation using the femur is 2.32 × femur length + 65.53 ± 3.94 cm. A female of the same ancestry would use the formula, 2.47 × femur length + 54.10 ± 3.72 cm. It is also important to note an individual's approximate age when determining stature. This is due to the shrinkage of the skeleton that naturally occurs as a person ages. After age 30, a person loses approximately one centimeter of their height every decade.

Determination of age

The determination of an individual's age by anthropologists depends on whether or not the individual was an adult or a child. The determination of the age of children, under the age of 21, is usually performed by examining the teeth. When teeth are not available, children can be aged based on which growth plates are sealed. The tibia plate seals around age 16 or 17 in girls and around 18 or 19 in boys. The clavicle is the last bone to complete growth and the plate is sealed around age 25. In addition, if a complete skeleton is available anthropologists can count the number of bones. While adults have 206 bones, the bones of a child have not yet fused resulting in a much higher number.

The aging of adult skeletons is not as straightforward as aging a child's skeleton as the skeleton changes little once adulthood is reached. One possible way to estimate the age of an adult skeleton is to look at bone osteons under a microscope. New osteons are constantly formed by bone marrow even after the bones stop growing. Younger adults have fewer and larger osteons while older adults have smaller and more osteon fragments. Another potential method for determining the age of an adult skeleton is to look for arthritis indicators on the bones. Arthritis will cause noticeable rounding of the bones. The degree of rounding from arthritis coupled with the size and number of osteons can help an anthropologist narrow down a potential age range for the individual.

Age estimation of living individuals

Age estimation of living individuals is carried out by estimating the biological age when the chronological age of the individual is unknown or uncertain because of the lack of valid identity documents. It is used to confirm if an individual has reached a specific age threshold in cases of criminal liability, asylum seekers and unaccompanied children, human trafficking, adoption, and competitive sports. Guidelines by the Study Group on Forensic Age Diagnostics (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Forensische Altersdiagnostik, AGFAD), propose that a three-step procedure should be followed for the age estimation: the first step is a physical examination; the second step include the assessment of the hand/wrist development using plain radiographs; the third step is a dental assessment. One of the most used methodologies for the estimation of age from the development of the hand and wrist is the Greulich and Pyle Atlas, whilst to assess dental development the most common method used so far is the 8-teeth technique developed by Demirjian et al.. Where the estimated age of the individual might be above 18 years of age, it is possible to use the development of the medial end of the clavicle. Traditionally, those undertaking age estimation in the living, adopt imaging techniques such as plain radiographies and CT scans to carry out the age estimation, however, lately, due to ethical issues surrounding the use of ionising medical imaging modalities for non-medical purposes (e.g., forensic purposes), magnetic resonance imaging, a radiation free medical imaging modality, is being investigated to develop new methodologies to estimate the age of living individuals.

Determination of ancestry

The estimation of individuals' ancestry is typically grouped into three groups. However, the use of these classifications is becoming much harder as the rate of interancestrial marriages increases. The maxilla can be used to help anthropologists estimate an individual's ancestry due to the three basic shapes: hyperbolic, parabolic, and rounded. In addition to the maxilla, the zygomatic arch and the nasal opening have been used to narrow down possible ancestry.

By measuring distances between landmarks on the skull as well as the size and shape of specific bones, anthropologists can use a series of equations to estimate ancestry. A program called FORDISC has been created that will calculate the most likely ancestry using complex mathematical formulas. This program is continually updated with new information from known individuals to maintain a database of current populations and their respective measurements. A 2009 study found that even in favourable circumstances, FORDISC 3.0 classifications have only a 1% confidence level. Research presented at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists concluded that ForDisc ancestry determination was not always consistent, and that the program should be used with caution. Determination of ancestry is incredibly controversial but often needed for police investigations to narrow down subject pool.

Other markers

Anthropologists are also able to see other markers present on the bones. Past fractures will be evident by the presence of bone remodeling but only for a certain amount of time. After around seven years, bone remodelling should make the presence of a fracture impossible to see. The examination of any fractures on the bones can potentially help determine the type of trauma they may have experienced. Cause of death is not determined by the forensic anthropologist, as they are not qualified to do so. However, they are able to determine the type of trauma experienced such as gun shot wound, blunt force, sharp force, or a mixture thereof. It is also possible to determine if a fracture occurred ante-mortem (before death), peri-mortem (at the time of death), or post-mortem (after death). Ante-mortem fractures will show signs of healing (depending on how long before death the fracture occurred) while peri- and post-mortem fractures will not. Peri-mortem fractures can incorporate quite a large range of time, as ante-mortem trauma that is unrelated directly to death may not have had time to begin the healing process. Peri-mortem fractures will usually appear clean with rounded margins and equal discolouration after death, while post-mortem breaks will appear brittle. Post-mortem breaks will often be a different colour to the surrounding bone i.e. whiter as they have been exposed to taphonomic processes for a different amount of time. However, depending on how long there is between a post-mortem break and removal this may not be obvious i.e. through re-interment by a killer. Diseases such as bone cancer might be present in bone marrow samples and can help narrow down the list of possible identifications.

Subfields

Forensic archaeology

The term "forensic archaeology" is not defined uniformly around the world, and is therefore practiced in a variety of ways.

Forensic archaeologists employ their knowledge of proper excavation techniques to ensure that remains are recovered in a controlled and forensically acceptable manner. When remains are found partially or completely buried the proper excavation of the remains will ensure that any evidence present on the bones will remain intact. The difference between forensic archaeologists and forensic anthropologists is that where forensic anthropologists are trained specifically in human osteology and recovery of human remains, forensic archaeologists specialize more broadly in the processes of search and discovery. In addition to remains, archaeologists are trained to look for objects contained in and around the excavation area. These objects can include anything from wedding rings to potentially probative evidence such as cigarette butts or shoe prints. Their training extends further to observing context, association and significance of objects in a crime scene and drawing conclusions that may be useful for locating a victim or suspect. A forensic archaeologist must also be able to utilize a degree of creativity and adaptability during times when crime scenes can not be excavated using traditional archaeological techniques. For example, one particular case study was conducted on the search and recovery of the remains of a missing girl who was found in a septic tank underground. This instance required unique methods unlike those of a typical archeological excavation in order to exhume and preserve the contents of the tank.

Forensic archaeologists are involved within three main areas. Assisting with crime scene research, investigation, and recovery of evidence and/or skeletal remains is only one aspect.

Processing scenes of mass fatality or incidents of terrorism (i.e. homicide, mass graves and war crimes, and other violations of human rights) is a branch of work that forensic archaeologists are involved with as well.

Forensic archaeologists can help determine potential grave sites that might have been overlooked. Differences in the soil can help forensic archaeologists locate these sites. During the burial of a body, a small mound of soil will form from the filling of the grave. The loose soil and increasing nutrients from the decomposing body encourages different kinds of plant growth than surrounding areas. Typically, grave sites will have looser, darker, more organic soil than areas around it. The search for additional grave sites can be useful during the investigation of genocide and mass graves to search for additional burial locations.

One other discipline to the career of a forensic archaeologist is teaching and research. Educating law enforcement, crime scene technicians and investigators, as well as undergraduate and graduate students is a critical part of a forensic archaeologist's career in order to spread knowledge of proper excavation techniques to other forensic personnel and to increase awareness of the field in general. Crime scene evidence in the past has been compromised due to improper excavation and recovery by untrained personnel. Forensic anthropologists are then unable to provide meaningful analyses on retrieved skeletal remains due to damage or contamination. Research conducted to improve archaeological field methods, particularly to advance nondestructive methods of search and recovery are also important for the advancement and recognition of the field.

There is an ethical component that must be considered. The capability to uncover information about victims of war crimes or homicide may present a conflict in cases that involve competing interests. Forensic archaeologists are often contracted to assist with the processing of mass graves by larger organisations that have motives related to exposure and prosecution rather than providing peace of mind to families and communities. These projects are at times opposed by smaller, human rights groups who wish to avoid overshadowing memories of the individuals with their violent manner(s) of death. In cases like these, forensic archaeologists must practice caution and recognize the implications behind their work and the information they uncover.

Forensic taphonomy

The examination of skeletal remains often takes into account environmental factors that affect decomposition. Forensic taphonomy is the study of these postmortem changes to human remains caused by soil, water, and the interaction with plants, insects, and other animals. In order to study these effects, body farms have been set up by multiple universities. Students and faculty study various environmental effects on the decomposition of donated cadavers. At these locations, cadavers are placed in various situations and their rate of decomposition along with any other factors related to the decomposition process are studied. Potential research projects can include whether black plastic causes decomposition to occur faster than clear plastic or the effects freezing can have on a dumped body.

Forensic taphonomy is divided into two separate sections, biotaphonomy and geotaphonomy. Biotaphonomy is the study of how the environment affects the decomposition of the body. Specifically it is the examination of biological remains in order to ascertain how decomposition or destruction occurred. This can include factors such as animal scavenging, climate, as well as the size and age of the individual at the time of death. Biotaphonomy must also take into account common mortuary services such as embalming and their effects on decomposition.

Geotaphonomy is the examination of how the decomposition of the body affects the environment. Geotaphonomy examinations can include how the soil was disturbed, pH alteration of the surrounding area, and either the acceleration or deceleration of plant growth around the body. By examining these characteristics, examiners can begin to piece together a timeline of the events during and after death. This can potentially help determine the time since death, whether or not trauma on the skeleton was a result of perimortem or postmortem activity, as well as if scattered remains were the result of scavengers or a deliberate attempt to conceal the remains by an assailant.

Education

Individuals looking to become forensic anthropologists first obtain a bachelor's degree in anthropology from an accredited university. During their studies they should focus on physical anthropology as well as osteology. In addition it is recommended that individuals take courses in a wide range of sciences such as biology, chemistry, anatomy, and genetics.

Once undergraduate education is completed the individual should proceed to graduate level courses. Typically, forensic anthropologists obtain doctorates in physical anthropology and have completed coursework in osteology, forensics, and archaeology. It is also recommended that individuals looking to pursue a forensic anthropology profession get experience in dissection usually through a gross anatomy class as well as useful internships with investigative agencies or practicing anthropologists. Once educational requirements are complete one can become certified by the forensic anthropology society in the region. This can include the IALM exam given by the Forensic Anthropology Society of Europe or the certification exam given by the American Board of Forensic Anthropology.

Typically, most forensic anthropologists perform forensic casework on a part-time basis, however there are individuals who work in the field full-time usually with federal or international agencies. Forensic anthropologists are usually employed in academia either at a university or a research facility.

Ethics

Like other forensic fields, forensic anthropologists are held to a high level of ethical standards due to their work in the legal system. Individuals who purposefully misrepresent themselves or any piece of evidence can be sanctioned, fined, or imprisoned by the appropriate authorities depending on the severity of the violation. Individuals who fail to disclose any conflict of interests or who fail to report all of their findings, regardless of what they may be, can face disciplinary actions. It is important that forensic anthropologists remain impartial during the course of an investigation. Any perceived bias during an investigation could hamper efforts in court to bring the responsible parties to justice. There is a substantial risk of confirmation bias from knowledge of context, especially with more ambiguous or complex cases.

In addition to the evidentiary guidelines forensic anthropologists should always keep in mind that the remains they are working with were once a person. If possible, local customs regarding dealing with the dead should be observed and all remains should be treated with respect and dignity.

Notable forensic anthropologists

| Name | Notable for | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Sue Black | Founding member of the British Association for Human Identification. Director of both the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification and the Leverhulme Centre for Forensic Science at the University of Dundee. | |

| Karen Ramey Burns | Worked in the investigation of genocides as well as the identification of victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina. | |

| Michael Finnegan | Worked on the identification of Jesse James. | |

| Richard Jantz | Co-developer of FORDISC. | |

| Ellis R. Kerley | Worked on the identification of Josef Mengele as well as the victims of the Jonestown mass suicide. | |

| William R. Maples | Worked on the identification of Czar Nicholas II and other members of the Romanov family as well as the examination of President Zachary Taylor's remains for arsenic poisoning. | |

| Fredy Peccerelli | Founder and director of the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation. | |

| Clyde Snow | Worked on the identification of King Tutankhamun and the victims of the Oklahoma City bombing as well as the investigation into the murder of John F. Kennedy. | |

| Mildred Trotter | Created statistical formulas for the calculation of stature based on human long bones through the examination of Korean War casualties. | |

| Kewal Krishan | Advancement of forensic anthropology in India. | |

| William M. Bass | Created the first body farm to investigate decomposition in various conditions, such as partially buried, buried during particular times of the year, left out in the open for animal scavengers, and burning. | |

| Kathy Reichs | Forensic anthropologist and author. Created the fictional character Dr. Temperance Brennan, and the inspiration for the TV series Bones. |

See also

- Craniofacial anthropometry

- Bioarchaeology

- Forensic pathology

- Forensic dentistry

- Forensic science, also known as "forensics"

- Forensic facial reconstruction

- List of important publications in anthropology

References

- ^ Nawrocki, Stephen P. (June 27, 2006). "An Outline Of Forensic Anthropology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-15. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- "National Crime Information Center: NCIC Files". FBI. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- "Notices". INTERPOL. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- McShane, Larry (July 19, 2014). "Forensic pathologist details grim work helping identify bodies after 9/11 in new book". Daily News. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- Hinkes, MJ (July 1989). "The role of forensic anthropology in mass disaster resolution". Aviat Space Environ Med. 60 (7 Pt 2): A60–3. PMID 2775124.

- "College Professor Gets the Call to Examine Plane Crashes and Crime Scenes". PoliceOne. July 28, 2002. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- Nuwer, Rachel (November 18, 2013). "Reading Bones to Identify Genocide Victims". The New York Times. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- Elson, Rachel (May 9, 2004). "Piecing together the victims of genocide / Forensic anthropologist identifies remains, but questions about their deaths remain". SFGate. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- Wendell Steavenson (2023-11-05). "The biblical archaeologist finding the victims Hamas burned". The Economist. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- Stewart, T. D. (1979). "In the Uses of Anthropology". Forensic Anthropology. Special Publication (11): 169–183.

- Shapiro, H. L. (1954). "Earnest Albert Hooton 1887-1954". American Anthropologist. 56 (6): 1081–1084. doi:10.1525/aa.1954.56.6.02a00090.

- Spencer, Frank (1981). "The Rise of Academic Physical Anthropology in the United States (1880-1980)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 56 (4): 353–364. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330560407.

- ^ Snow, Clyde Collins (1982). "Forensic Anthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 11: 97–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.11.100182.000525.

- ^ Cobb, W. Montague (1959). "Thomas Wingate Todd, M.B., Ch.B., F.R.C.S. (Eng.), 1885-1938". Journal of the National Medical Association. 51 (3): 233–246. PMC 2641291. PMID 13655086.

- Buikstra, Jane E.; Ubelaker, Douglas H. (1991). "Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains". Arkansas Archaeology Survey Research Series. 44.

- McKern, T. W.; Stewart, T. D. (1957), Skeletal Age Changes in Young American Males (PDF), Headquarters, Quartermaster Research and Developmental Command, archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016

- Trotter, M.; Gleser, G.C. (1952). "Estimation of Stature from Long Bones of American Whites and Negroes". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 10 (4): 463–514. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330100407. PMID 13007782.

- Buikstra, Jane E.; King, Jason L.; Nystrom, Kenneth (2003). "Forensic Anthropology and Bioarchaeology in the American Anthropologist: Rare but Exquisite Gems". American Anthropologist. 105 (1): 38–52. doi:10.1525/aa.2003.105.1.38.

- Golda, Stephanie (2010). "A Look at the History of Forensic Anthropology: Tracing My Academic Genealogy". Journal of Contemporary Anthropology. 1 (1).

- "Identification Of Skeletal Remains" (PDF). forensicjournals.com. November 5, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- "4 Ways to Determine Sex (When All You Have is a Skull". Forensic Outreach. October 8, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- Hawks, John (November 15, 2011). "Determining sex from the cranium". Archived from the original on 2015-09-15. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- "Differences Between Male Skull and Female Skull". juniordentist.com. September 24, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- "how do archaeologists determine the sex of a skeleton". marshtide. April 27, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- "Male or Female". Smithsonian National Museum of National History. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- Cardoso, Hugo F.V. (January 2008). "Sample-specific (universal) metric approaches for determining the sex of immature human skeletal remains using permanent tooth dimensions". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (1): 158–168. Bibcode:2008JArSc..35..158C. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.02.013.

- Harris, Edward F.; Lease, Loren R. (November 2005). "Mesiodistal tooth crown dimensions of the primary dentition: A worldwide survey". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 128 (3): 593–607. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20162. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 15895432.

- Paknahad, Maryam; Vossoughi, Mehrdad; Ahmadi Zeydabadi, Fatemeh (November 2016). "A radio-odontometric analysis of sexual dimorphism in deciduous dentition". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 44: 54–57. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2016.08.017. PMID 27611965.

- Kondo, Shintaro; Townsend, Grant C.; Yamada, Hiroyuki (December 2005). "Sexual dimorphism of cusp dimensions in human maxillary molars". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 128 (4): 870–877. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20084. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 16110475.

- Stroud, J L; Buschang, P H; Goaz, P W (August 1994). "Sexual dimorphism in mesiodistal dentin and enamel thickness". Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. 23 (3): 169–171. doi:10.1259/dmfr.23.3.7835519. ISSN 0250-832X. PMID 7835519.

- Garn, Stanley M.; Arthur B. Lewis; Rose S. Kerewsky (September 1967). "Genetic Control of Sexual Dimorphism in Tooth Size". Journal of Dental Research. 46 (5): 963–972. doi:10.1177/00220345670460055801. ISSN 0022-0345. PMID 5234039. S2CID 27573899.

- García-Campos, Cecilia; Martinón-Torres, María; Martín-Francés, Laura; Martínez de Pinillos, Marina; Modesto-Mata, Mario; Perea-Pérez, Bernardo; Zanolli, Clément; Labajo González, Elena; Sánchez Sánchez, José Antonio (June 2018). "Contribution of dental tissues to sex determination in modern human populations" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 166 (2): 459–472. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23447. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 29460327. S2CID 4585225.

- Sorenti, Mark; Martinón-Torres, María; Martín-Francés, Laura; Perea-Pérez, Bernardo (2019-03-13). "Sexual dimorphism of dental tissues in modern human mandibular molars". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 169 (2): 332–340. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23822. PMID 30866041. S2CID 76662620.

- ^ "Biological Profile / Stature" (PDF). Simon Fraser University. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- Mall, G. (March 1, 2001). "Sex determination and estimation of stature from the long bones of the arm". Forensic Sci Int. 117 (1–2): 23–30. doi:10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00445-x. PMID 11230943.

- Khan, Md Alinawaz; Badakali, Ashok V; Neelannavar, Ramesh (2023-12-19). "Cross Sectional Study to Correlate the Stature and Percutaneous Length of Ulna Bone of Pediatrics Age Group in North Karnataka State of India". International Journal of Medical Students: S100. doi:10.5195/ijms.2023.2327. ISSN 2076-6327.

- Hawks, John (September 6, 2011). "Predicting stature from bone measurements". Archived from the original on 2015-09-15. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- Garwin, April (2006). "Stature". redwoods.edu. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- "Skeletons are good age markers because teeth and bones mature at fairly predictable rates" (PDF). Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Young or Old?". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- "Quick Tips: How To Estimate The Chronological Age Of A Human Skeleton — The Basics". All Things AAFS!. August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- "Skeletons as Forensic Evidence". Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- Schmeling, A; Dettmeyer, R; Rudolf, E; Vieth, V; Generic, G (2016). "Forensic Age Estimation: Methods, Certainty, and the Law". Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 133 (4): 44–50. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2016.0044. PMC 4760148. PMID 26883413.

- Black, S. M.; Aggrawal, A.; Payne-James, J. (2010). Age estimation in the living: The practitioners guide. Chichester, West Sussex: UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Schmeling, A.; Grundmann, C.; Fuhrmann, A.; Kaatsch, H.; Knell, B.; Ramsthaler, F.; Reisinger, W.; Riepert, T.; Ritz-Timme, S.; Rösing, F.; Rötzscher, K.; Geserick, G. (2008). "Criteria for age estimation in living individuals". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 122 (6): 457–460. doi:10.1007/s00414-008-0254-2. PMID 18548266. S2CID 21480200.

- Greulich, W.; Pyle, S. (1959). Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of Hand and Wrist. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Demirjian, A.; Goldstein, H.; Tanner, J.M. (1973). "A new system of dental age assessment". Human Biology. 45 (2): 211–227. PMID 4714564.

- Schmeling, A.; Schulz, R.; Reisinger, W.; Mühler, M.; Wernecke, K.; Geserick, G. (2004). "Studies on the time frame for ossification of the medial clavicular epiphyseal cartilage in conventional radiography". Int. J. Legal Med. 118 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1007/s00414-003-0404-5. PMID 14534796. S2CID 2723880.

- European Asylum Support Office (2018). Age Assessment Practice in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Doyle, E.; Márquez-Grant, N.; Field, L.; Holmes, T.; Arthurs, O.J.; van Rijn, R.R.; Hackman, L.; Kasper, K.; Lewis, J.; Loomis, P.; Elliott, D.; Kroll, J.; Viner, M.; Blau, S.; Brough, A.; Martín de las Heras, S.; Garamendi, P.M. (2019). "Guidelines for best practice: Imaging for age estimation in the living" (PDF). Journal of Forensic Radiology and Imaging. 16: 38–49. doi:10.1016/j.jofri.2019.02.001. S2CID 86423929.

- "Anthropological Views". National Institute of Health. June 5, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- "Analysis of Skeletal Remains". Westport Public Schools. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- "Activity: Can You Identify Ancestry?" (PDF). Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- "Ancestry, Race, and Forensic Anthropology". Observation Deck. March 31, 2014. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- Elliott, Marina; Collard, Mark (2009-11-11). "Fordisc and the determination of ancestry from cranial measurements". Biology Letters. 2009 (5). The Royal Society: 849–852. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0462. PMC 2827999. PMID 19586965.

- "Poster: Elliott and Collard 2012 Going head to head: FORDISC vs CRANID in the determination of ancestry from craniometric data". meeting.physanth.org. Archived from the original on 2021-04-19. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- Smith, Ashley C. (December 10, 2010). "Distinguishing Between Antemortem, Perimortem, and Postmortem Trauma". Retrieved August 20, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Groen, W.J. Mike; Márquez-Grant, Nicholas; Janaway, Robert C. (2015). Forensic archaeology: A global perspective. ISBN 9781118745977.

- "Forensic Archaeology". Chicora Foundation. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ Schultz, Dupras (2008). "The Contribution of Forensic Archaeology to Homicide Investigations". Homicide Studies. 12 (4): 399–413. doi:10.1177/1088767908324430. S2CID 145281304.

- Nawrocki, Stephen P. (June 27, 2006). "An Outline Of Forensic Archeology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-29. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- Sigler-Eisenberg (1985). "Forensic Research: Expanding the Concept of Applied Archaeology". American Antiquity. 50 (3): 650–655. doi:10.1017/S0002731600086467. S2CID 160047810.

- "Forensic Archaeology". Simon Fraser University. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- Haglund, William (2001). "Archaeology and Forensic Death Investigations". Historical Archaeology. 35 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1007/BF03374524. PMID 17595746. S2CID 44380029.

- Steele, Caroline (2008-08-20). "Archaeology and the Forensic Investigation of Recent Mass Graves: Ethical Issues for a New Practice of Archaeology". Archaeologies. 4 (3): 414–428. doi:10.1007/s11759-008-9080-x. ISSN 1555-8622. S2CID 4948727.

- Pokines, James; Symes, Steven A. (2013-10-08). Manual of Forensic Taphonomy. CRC Press. ISBN 9781439878415.

- Killgrove, Kristina (June 10, 2015). "These 6 'Body Farms' Help Forensic Anthropologists Learn To Solve Crimes". forbes.com. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "Forensic taphonomy". itsgov.com. December 8, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ Nawrocki, Stephen P. (June 27, 2006). "An Outline Of Forensic Taphonomy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- Hall, Shane (21 July 2012). "Education Required for Forensic Anthropology". Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- "FASE/IALM Certification". Forensic Anthropology Society of Europe. Archived from the original on 2015-02-25. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- "Certification Examination General Guidelines" (PDF). American Board of Forensic Anthropology. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- "ABFA – American Board of Forensic Anthropology". Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- "Code of Ethics and Conduct" (PDF). Scientific Working Group for Forensic Anthropology. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- "Code of Ethics and Conduct" (PDF). American Board of Forensic Anthropology. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- Warren, Michael W.; Friend, Amanda N.; Stock, Michala K. (2017-12-15). "Navigating cognitive bias in forensic anthropology". Forensic Anthropology. pp. 39–51. doi:10.1002/9781119226529.ch3. ISBN 978-1-119-22638-3.

- Cooper, Glinda S.; Meterko, Vanessa (2019-04-01). "Cognitive bias research in forensic science: A systematic review". Forensic Science International. 297: 35–46. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.01.016. ISSN 0379-0738. PMID 30769302.

- "About Us". British Association for Human Identification. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Shearer, Lee (January 13, 2012). "Forensic anthropologist Burns dies, a former Athens resident". Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Hrenchir, Tim (April 26, 1999). "Scientist who confirmed grave of Jesse James to speak". Archived from the original on 2015-09-30. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Jantz, R.L.; Ousley, S.D. (2005). "FORDISC 3.1 Personal Computer Forensic Discriminant Functions". Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Burkhart, Ford (September 12, 1998). "Ellis R. Kerley Is Dead at 74; A Forensic Sherlock Holmes". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Herszenhorn, David M. (March 1, 1997). "William R. Maples, 59, Dies; Anthropologist of Big Crimes". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- "Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala". Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- McFadden, Robert (May 16, 2014). "Clyde Snow, Sleuth Who Read Bones From King Tut's to Kennedy's, Dies at 86". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Byers, Steven N. (2011). Introduction to forensic anthropology (4th ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education. p. 490. ISBN 978-0205790128. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- "PU Prof, student's study accepted by US forensic sciences academy". Hindustan Times. February 9, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- Buikstra et al. 2003

External links

- University of Bournemouth

- University of Edinburgh

- University of Dundee Archived 2011-11-08 at the Wayback Machine

- American Board of Forensic Anthropology

- American Academy of Forensic Sciences

- American Association of Physical Anthropologists

- Maples Center for Forensic Medicine at the University of Florida

- Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation (in Spanish)

- ForensicAnth.com – Forensic anthropological news stories from across the globe

- The Why Files: Bodies and Bones Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Struers replica technique for forensic investigation

- The Forensic Anthropology Forum – forensic anthropology news and continuing education

- Forensic Anthropology – Theoretical and Practical Information

- Forensic Anthropology Summer Camp – Experience

- Osteointeractive – Forensic Anthropology Blog