Not to be confused with Brusselization.

The Francization of Brussels refers to the evolution, over the past two centuries, of this historically Dutch-speaking city into one where French has become the majority language and lingua franca. The main cause of this transition was the rapid, compulsory assimilation of the Flemish population, amplified by immigration from France and Wallonia.

The rise of French in public life gradually began by the end of the 18th century, quickly accelerating as the new capital saw a major increase in population following Belgian independence. Dutch – of which standardization in Belgium was still very weak — could not compete with French, which was the exclusive language of the judiciary, the administration, the army, education, high culture and the media. The value and prestige of the French language was so universally acknowledged that after 1880, and more particularly after the turn of the century, proficiency in French among Dutch-speakers increased spectacularly.

Although the majority of the population remained bilingual until the second half of the 20th century, the original Brabantian dialect was often no longer passed on from one generation to another, leading to an increase of monolingual French-speakers from 1910 onwards. This language shift weakened after the 1960s, as the language border was fixed, the status of Dutch as an official language was confirmed, and the economic center of gravity shifted northward to Flanders.

However, with the continuing arrival of immigrants (most either from French-speaking countries or more familiar with French) and the post-war emergence of Brussels as a center of international politics, the relative position of Dutch continued to decline. Simultaneously, as Brussels' urban area expanded, a further number of Dutch-speaking municipalities in the Brussels Periphery also became predominantly French-speaking. This phenomenon of expanding Francization (dubbed the "oil slick" by its opponents), remains, together with the future of Brussels, one of the most controversial topics in Belgian politics and public discourse.

Historical origins

Middle Ages

Around the year 1000, the County of Brussels became a part of the Duchy of Brabant (and therefore of the Holy Roman Empire) with Brussels as one of the Duchy's four capitals, along with Leuven, Antwerp, and 's-Hertogenbosch. Dutch was the sole language of Brussels, as in the other three cities. However, not all of Brabant was Dutch-speaking. The area south of Brussels, around the town of Nivelles, was a French-speaking area roughly corresponding to the modern province of Walloon Brabant.

Initially, Latin was used as an official language in Brussels, just like in most of Europe. From the late 13th century, people began to shift usage to the vernacular. This occurrence took place in Brussels and then in other Brabantian cities, which had all eventually transformed by the 16th century. Official city orders and proclamations were thenceforth gradually written in Middle Dutch. Until the late 18th century, Dutch remained the administrative language of the Brussels area of the Duchy of Brabant. As part of the Holy Roman Empire, Brabantian cities enjoyed many freedoms, including choice of language. Before 1500, there were almost no French documents in the Brussels city archives. By comparison, in the cities in the neighboring County of Flanders such as Bruges, Ghent, Kortrijk and Ypres the percentage of French documents in city archives fluctuated between 30% and 60%. Such a high level of French influence had not yet developed in the Dutch-speaking areas of the Duchy of Brabant, including Brussels.

After the death of Joanna, Duchess of Brabant, in 1406, the Duchy of Brabant became a part of the Duchy of Burgundy and the use of the French language slowly increased in the region. In 1477, Burgundian duke Charles the Bold perished in the Battle of Nancy. Through the marriage of his daughter Mary of Burgundy (who was born in Brussels) to Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, the Low Countries fell under Habsburg sovereignty. Brabant was integrated into this composite state, and Brussels flourished as the capital of the prosperous Burgundian Netherlands, also known as the Seventeen Provinces. After the death of Mary in 1482, her son Philip the Handsome succeeded as Duke of Burgundy and Brabant. In 1506, he became the king of Castile, and hence the period of the Spanish Netherlands began.

Spanish rule

After 1531, Brussels was known as the Princely Capital of the Netherlands. After the division of the Netherlands resulting from the Eighty Years' War and in particular from the fall of Antwerp to the Spanish, Netherlands' economic and cultural centers migrated to the northern Dutch Republic. About 150,000 people, mainly stemming from the intellectual and economic elites, fled north. Brabant and Flanders were engulfed in the Counter-Reformation, and the Catholic priests continued to perform the liturgy in Latin.

Dutch was seen as the language of Calvinism and was thus considered to be anti-Catholic. In the context of the Counter-Reformation, many clerics of the Low Countries had to be educated at the French-speaking University of Douai. However, Dutch was not utterly excluded in the religious domain. For instance, Ferdinand Brunot reported in 1638 that, in Brussels, the Jesuits "preached three times a week in Flemish and twice in French". While Dutch became standardized by the Dutch Republic, dialects continued to be spoken in the south. As in other places in Europe during the 17th century, French grew as a language of the nobility and upper class of society. The languages used in the central administration during this time were both French and, to a lesser extent, Spanish. Some French-speaking nobility established themselves in the hills of Brussels (in the areas of Coudenberg and Zavel), bringing with them primarily French-speaking Walloon personnel. This attracted a considerable number of other Walloons to Brussels who came in search of work. This Walloon presence led to the adoption of Walloon words in the Brussels flavor of Brabantian Dutch, but the Walloon presence was still too small to prevent them from being assimilated into the Dutch-speaking majority.

Austrian rule

Following the Peace of Utrecht, Spanish sovereignty over the Southern Netherlands was transferred to the Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg. This event started the era of the Austrian Netherlands.

In the 18th century, there were already complaints about the waning use of Dutch in Brussels, which had been reduced to the status of "street language". There were various reasons for this. The Habsburgs' repressive policies after the division of the Low Countries and the following exodus of the intellectual elite towards the Dutch Republic left Flanders bereft of its social upper class. After the 17th century's end, when the Dutch Golden Age ended and the Dutch Republic began declining, Dutch lost even more prestige as a language for politics, culture, and business. Meanwhile, French culture was quickly spreading. For instance, the Theater of La Monnaie showed 95% of plays in French by the mid-18th century. During the War of the Austrian Succession, Brussels was under French rule between 1745 and 1749. Under these circumstances, especially after 1780, French became the adopted language of much of the Flemish bourgeoisie, who were later pejoratively labelled Franskiljons (loosely: little Frenchies). The lower classes got progressively poorer, and, by 1784, 15% of the population was in poverty. The small French-speaking minority was quite affluent and constituted the social upper class.

The percentage of the Brussels population using French in public life was between 5 and 10% in 1760, increasing to 15% in 1780. According to authenticated archives and various official documents, it appears that a fifth of municipal declarations and official orders were written in French. Twenty years later this rose to a quarter; however, over half of the official documents in French originated in the French-speaking bourgeoisie, who made up just a tenth of the population. In 1760, small businesses and artisans wrote only 4% of their documents in French; by 1780 this had risen to 13%. In private life, however, Dutch was still by far the most-used language. For the Austrian Habsburg administration, French was the language of communication, although the communiqué from the Habsburgs was seldom seen by commoners of Brussels.

French rule

Following the campaigns of 1794 in the French Revolutionary Wars, the Low Countries were annexed by the French First Republic, ending Habsburg rule in the region. The Flemish were heavily repressed by the French, who instituted heavy-handed policies that completely paralyzed the economy. Within this period of systematic exploitation, about 800,000 inhabitants fled the Southern Netherlands, and the population of Brussels decreased from 74,000 in 1792 to 66,000 in 1799. The French occupation led to further suppression of Dutch across the country, including its abolition as an administrative language. With the motto "one nation, one language", French became the only accepted language in public life, as well as in economic, political, and social affairs. The measures of the successive French governments, and in particular the 1798 massive conscription into the French army, were particularly unpopular within the Flemish segment of the population and caused the Peasants' War. The Peasant's War is often seen as the starting point of the modern Flemish movement. From this period until the 20th century, Dutch was seen in Belgium as a language of the poor and illiterate. In Flanders, as well as other areas in Europe, the aristocracy quickly adopted French. The French occupation laid the foundations for a Francization of the Flemish middle class aided by an exceptional French-language educational system.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Napoleonic Office of Statistics found that Dutch was still the most frequently spoken language in both the Brussels arrondissement and Leuven. An exception included a limited number of districts within the City of Brussels, where French had become the most used language. In Nivelles, Walloon was the most spoken language. Inside of the Small Ring of Brussels (the Pentagon), French was the leading language of street markets and districts such as the Coudenberg and the Sablon/Zavel, while Dutch dominated in the harbor, the Schaerbeek Gate and the Leuven Gate areas. The first city walls were gradually dismantled during the 15th century to the 17th century, and the outer second walls (where the Small Ring now stands) were demolished between 1810 and 1840, so that the city could grow and incorporate the surrounding settlements.

Immediately after the French capture, the use of Dutch was forbidden in Brussels' Town Hall. The Francization policy, instituted to unify the state, were aimed at the citizens who were to assume power from the nobility as was done in the French Revolution. However, the French rulers rapidly understood it was not possible to force local populations, speaking languages very different from French, to suddenly use it. The Francization of the Dutch-speaking parts of the Low Countries, therefore, remained limited to the higher levels of the local administration and upper-class society. The effect on lower social classes, of whom 60% were illiterate, was small. Life on the streets was greatly affected as, by law, all notices, street names, etc. were required to be written in French, and official documents were to be written solely in French, although "when needed", a non-legally-binding translation could be permitted. Simultaneously, businesses from the rural areas were told not to continue operating if they were not proficient in French. In addition, the law stated that all court pleas, sentences, and other legal materials were to be written solely in French unless practical considerations made this impossible. These measures increased the percentage of official documents written in French from 60% around the start of the 19th century to 80% by 1813. Although mainly used in higher social circles, a more appropriate measure of actual language use might include an observation of written testaments, three-fourths of which in 1804 were written in Dutch, indicating that the upper classes still mainly used Dutch around the start of the 19th century.

Dutch rule

In 1815, following the final defeat of Napoleon, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands was created by the Congress of Vienna, joining the Southern Netherlands with the former Dutch Republic. Shortly after the formation of the new kingdom, at the request of Brussels businesses, Dutch once again became the official language of Brussels. Nevertheless, the union of the Netherlands and Belgium did little to lessen the political and economic power of French in Flanders, where it remained the aristocracy's language. Brussels and The Hague were dual capitals of the Kingdom, and in the Parliament, the Belgian delegates spoke only French. King William I of the Netherlands wanted to develop present-day Flanders to the level of the Northern Netherlands, and instituted a wide network of schools in the local language of the people. He made Dutch the single official language of the Flemish provinces, and this was also implemented in bilingual Brabant and Brussels. The Walloon provinces remained monolingually French. The king hoped to make Dutch the sole language of the nation, but the French-speaking citizenry, the Catholic Church, and the Walloons resisted this move. The French-speaking population feared that their opportunities for participation in government were threatened and that they would become unneeded elements of the new kingdom. Under pressure from these groups, in 1830, the king reintroduced a language freedom policy throughout all of present-day Belgium. This nullified the monolingual status of Brussels and the Flemish provinces.

Important for the later development of the Dutch language was that the Flemish population experienced a certain amount of contact with the northern Standard Dutch during the kingdom's short reign. The Catholic Church viewed Dutch as a threatening element representative of Protestantism, while the Francophone aristocracy still viewed Dutch as a language subordinate to French. These views helped contribute to the Belgian Revolution and to the creation of an independent and officially monolingual Francophone Kingdom of Belgium, established in 1830. This strong preference for French would greatly influence language use in Brussels.

Belgian Revolution

See also: Language legislation in Belgium

After the Belgian Revolution, the bourgeoisie in Brussels began to increasingly use French. Numerous French and Walloon immigrants moved to Brussels, and for the first time in mass numbers the Flemish people began switching to French.

By October 16, 1830 King William I had already rescinded a policy that named Dutch as the official language of Brussels. The sole official language of the newly created centralized state was French, even though a majority of the population was Flemish. French became the language of the court, the administration, the army, the media, and of culture and education. With more French being spoken, societal progress, culture, and universalism gave it an aura of "respectibility". In contrast, Dutch garnered little consideration and was deemed a language for peasants, farmers, and poor workers. In addition to the geographical language border between Flanders and Wallonia, there was in fact also a social language border between the Dutch-speakers and French-speakers. French was the language of politics and economics and a symbol of upward social mobility. French poet Charles Baudelaire, during his short stay in Brussels, complained of the contemporary bourgeoisie's hypocrisy:

In Brussels, people do not really speak French, but pretend that they do not speak Flemish. For them it shows good taste. The proof that they actually do speak good Flemish is that they bark orders to their servants in Flemish.

— Baudelaire, 1866

The new Belgian capital remained a mostly Dutch-speaking city, where the inhabitants spoke a local South Brabantian dialect. A minority of French-speaking citizens, mainly those who had immigrated from France during the previous decades, constituted 15% of the population. Despite this, the first mayor of Brussels after the revolution, Nicolas-Jean Rouppe, declared French to be the administration's sole language. The political center of Brussels attracted the economic elite, and Brussels soon acquired French-speaking upper and middle classes. In 1846, 38% of the city declared themselves being French-speaking, while this percentage was 5% in Ghent and 2% in Antwerp. Many supposed French-speakers were actually Flemish bourgeois with Dutch-speaking roots. In 1860, 95% of the Flemish population spoke Dutch, although these people had hardly any economic and political power and deemed a good knowledge of French necessary to attain higher social status and wealth.

Role of education

Brussels attracted many immigrants from Flanders, where economic strife and hunger were widespread in the 1840s. Native Flemish Brussels residents harbored a sense of superiority over the other Flemish immigrants from the poor countryside, which manifested itself in the decision to speak the "superior" French language.

In two or three generations, the new immigrants themselves began to speak French. A typical family might have Dutch-speaking grandparents, bilingual parents, and French-speaking children. The exclusively French educational system played an important role in this changing language landscape. Dutch was mainly ignored as a school subject. From 1842, Dutch was removed from the first four years of boys' schools, although in later school grades, it could be studied. In girls' schools and Catholic schools, Dutch was taught even less, even though Dutch was still the native tongue of a majority of the students.

Just after the mayoral inauguration of Charles Buls in 1881, elementary schools that taught Dutch were reopened in 1883. In these schools, the first two years of lessons were given in Dutch, soon after which students transitioned into French-speaking classes. The proposal by Buls was initially poorly received by the local councils, although they were later accepted when studies showed that when students had acquired a good understanding of Dutch, they more easily obtained French speaking skills. The dominance of French in education was not affected, since most schooling in later years was still in French. Because of the authoritative position that French enjoyed in Belgium and the misconceptions of Buls' plan, many Flemish children were still sent to a French school to better master the language. This was made possible by the idea of "freedom of the head of household", which stipulated that parents were allowed to send their children to any school they wished, regardless of the child's mother tongue. Since most pupils were sent to French schools rather than Dutch schools, after the end of World War I there was not a single Dutch class left in central Brussels. In the thirteen municipalities that constituted the Brussels metropolitan area, there were 441 Dutch classes and 1,592 French classes, even though the French-speaking population made up just under one-third of the total.

As a result of the propagation of the bilingual education system, Dutch was no longer being passed down by many Flemish parents to their children. French was beginning to be increasingly used as the main language spoken at home by many Flemings. In Flanders, education played less of a role in Francization because most schools continued to teach in Dutch.

French-speaking immigration

During the 19th century, many political asylum seekers sought refuge in Brussels, mainly coming from France. The first wave came in 1815 bringing Jacobins and Bonapartists; a second wave came in 1848 bringing French republicans and Orléanists, a third came after the 1851 French coup d'état, and a fourth came in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War. Asylum seekers and other immigrants also came from other parts of Europe such as Italy, Poland, Germany, and Russia. They preferred to speak French rather than Dutch when they arrived, which further intensified Francization.

As the capital of the new kingdom, Brussels also attracted a large number of Walloon migrants. In contrast to Flemish citizens of Brussels, who came primarily from the lower social classes, the Walloon newcomers belonged mainly to the middle class. The Walloon and French migrants lived predominantly in the Marollen district of Brussels, where Marols, a mixture of Brabantian Dutch, French, and Walloon, was spoken. Despite the fact that many lower-class Walloons also made their way to Brussels, the perception of French as an intellectual and elite language did not change. Additionally, Brussels received a considerable number of French-speaking members of the Flemish bourgeoisie.

Between 1830 and 1875 the population of the City of Brussels grew from approximately 100,000 to 180,000; the population of the metropolitan area soared to 750,000 by 1910.

Early Flemish movement in Brussels

In contrast to the rest of Flanders, French in Brussels was seen less as a means of oppression but rather as a tool for social progress. In the first decade after the independence of Belgium, the neglect of the Dutch language and culture gradually caused increasingly greater dissatisfaction in the Flemish community. In 1856, the "Grievances Commission" was established to investigate the problems of the Flemings. It was devoted to making the administration, military, educational system and judicial system bilingual, but was politically ignored. Another group to decry the problems of the Flemings was "Vlamingen Vooruit" ("Flemings Forward"), founded in 1858 in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode. Members included Charles Buls, mayor of Brussels, and Léon Vanderkindere, mayor of Uccle. Although Brussels was 57% Dutch-speaking in 1880, Flemish primary schools were prohibited until 1883. In 1884, the municipal government decided to allow birth, death, and marriage certificates to be written in Dutch. However, only a tenth of the population made use of these opportunities, suggesting that in the minds of Brussels' inhabitants, French was the normal way of conducting these matters. In 1889, Dutch was once again allowed in courtrooms, but only for use in oral testimony.

In the late 19th century, the Flemish movement gained even more strength and demanded Belgium be made bilingual. This proposal was rejected by French speakers, who feared a "Flemishization" of Wallonia as well as the prospect of having to learn Dutch to obtain a job in the civil service. The Flemings adapted their goals to the realities of the situation and devoted themselves to a monolingual Flanders, which Brussels was still socially a part of. The Flemings hoped to limit the spread of French in Flanders by restricting the areas in which French was an official language. In 1873 in the Sint-Jans-Molenbeek district of Brussels, Flemish laborer Jozef Schoep refused to accept a French-language birth certificate. He was ordered to pay a fine of 50 francs. His case generated considerable controversy and shortly thereafter the Coremans Law was introduced, which allowed Dutch to be used by Dutch speakers in court.

In general, the Flemish movement in Brussels did not garner much support for its plans regarding the use of Dutch. Each attempt to promote Dutch and limit the expansion of French influence as a symbol of social status was seen as a means to stifle social mobility rather than as a protective measure as it was seen in the rest of Flanders. Whereas in other Flemish cities such as Ghent in which the Flemish laborers were dominated by a French-speaking upper class, in Brussels it was not as easy to make such a distinction because so many Walloons made up a large portion of the working class. The linguistic heterogeneity, combined with the fact that most of the workers' upper class spoke French, meant that the class struggle for most workers in Brussels was not seen as a language struggle as well. Ever since the start of the 20th century, the workers' movement in Brussels defended bilingualism, so as to have a means of emancipation for the local working class. This, along with the educational system, facilitated the Francization of thousands of Brussels residents.

Early language laws

See also: Language legislation in Belgium

By the 1870s, most municipalities were administered in French. With the De Laet law in 1878, a gradual change started to occur. From that point forward, in the provinces of Limburg, Antwerp, West Flanders and East Flanders, and in the arrondissement of Leuven, all public communication was given in Dutch or in both languages. For the arrondissement of Brussels, documents could be requested in Dutch. Nonetheless, by 1900 most large Flemish cities, cities along the language border, and the municipalities of the Brussels metropolitan area were still administered in French.

In 1921, the territoriality principle was recognized, which solidified the outline of the Belgian language border. The Flemings hoped that such a language border would help to curb the influx of French in Flanders. Belgium became divided into three language areas: a monolingual Dutch-speaking area in the north (Flanders), a monolingual French-speaking area in the south (Wallonia), and a bilingual area (Brussels), even though the majority of Brussels residents spoke primarily Dutch. The municipalities in the Brussels metropolitan region, the bilingual region of Belgium, could freely choose either language to be used in administrative purposes. The town government of Sint-Stevens-Woluwe, which lies in present-day Flemish Brabant, was the only one to opt for Dutch over French.

Language censuses

The language law of 1921 was elaborated upon by a further law in 1932. Dutch was made an official language within the central government, the (then) four Flemish provinces, as well as the arrondissements of Leuven and Brussels (excepting the Brussels metropolitan area as a whole). The law also stipulated that municipalities on the language border or near Brussels would be required to provide services in both languages when the minority exceeded 30%, and the administrative language of a municipality would be changed if the language minority grew to greater than 50%. This was to be regulated by a language census every ten years, although the validity of the results from Flanders was frequently questioned. In 1932, Sint-Stevens-Woluwe, now a part of the Zaventem municipality, became the first municipality in Belgian history to secede from the bilingual Brussels metro region because the French-speaking minority percentage fell to below 30%. This did not sit well with some French speakers in Brussels, some of whom formed a group called the "Ligue contre la flamandisation de Bruxelles" (League against the Flemishification of Brussels), which campaigned against what they saw as a form of "Flemish tyranny". Before the introduction of French as an official language of Ganshoren and Sint-Agatha-Berchem, the group also objected to the bilingual status of Ixelles. The group also strongly defended the "freedom of the head of household", a major factor in the process of Francization.

Evolution in the City of Brussels proper

While the Brussels metropolitan area grew quickly, the population of the City of Brussels proper declined considerably. In 1910, Brussels had 185,000 inhabitants; in 1925 this number fell to 142,000. The reasons for this depopulation were manifold. First, the fetid stench of the disease-laden Senne river caused many to leave the city. Second, cholera broke out in 1832 and 1848, which led to the Senne being completely covered over. Third, the rising price of property and rental rates caused many inhabitants to search for affordable living situations elsewhere. Higher taxes on patents, which were up to 30% higher than those in neighboring municipalities, stifled economic development and drove up the cost of city living. These higher patent prices were abandoned in 1860. Finally, the industrialization that occurred in the neighboring areas drew workers out of the city. These social changes helped speed the process of Francization in the central city. In 1920, three bordering municipalities, each having a large number of Dutch-speaking inhabitants, were amalgamated into the City of Brussels.

According to the language census of 1846, 61% of Brussels residents spoke Dutch and 39% spoke French. The census of 1866 permitted residents to answer "both languages", although it was unstated whether this meant "knowledge of both languages" or "use of both languages", nor whether or not either was the resident's mother tongue. In any case, 39% answered Dutch, 20% French, and 38% "both languages". In 1900, the percentage of monolingual French speakers overtook the percentage of monolingual Dutch speakers, although this was most likely caused by the growing number of bilingual speakers. Between 1880 and 1890, the percentage of bilingual speakers rose from 30% to 50%, and the number of monolingual Dutch speakers declined from 36% in 1880 to 17% in 1910. Although the term "bilingual" was misused by the government to showcase a large number of French speakers, it is clear that French gained acceptance in both the public and private lives of Dutch-speaking Brussels residents.

Expansion of the metropolitan area

Beyond the city of Brussels, the municipalities of Ixelles, Saint-Gilles, Etterbeek, Forest, Watermael-Boitsfort and Saint-Josse saw the most widespread adoption of the French language over the following century. In Ixelles, the proportion of Dutch monolinguals fell from 54% to 3% between 1846 and 1947, while during the same time, the proportion of monolingual Francophones grew from 45% to 60%. Whereas in 1846 Saint-Gilles was still 83% Dutch-speaking, one hundred years later, half of its population spoke only French, and 39% were bilingual. Similarly, Etterbeek changed from a 97% Dutch-speaking village to an urban neighborhood in which half of its inhabitants spoke only French. The same phenomenon applied to Forest and Watermael-Boitsfort, where they went from completely Dutch-speaking to half monolingual French and half bilingual, with monolingual Dutch speakers at only 6%. In Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, the proportion of monolingual Dutch speakers equalled that of French speakers in 1846, but by 1947 only 6% were monolingual Dutch speakers, and 40% were monolingual French speakers.

In 1921 the metropolitan area was expanded further. The municipalities of Laken, Neder-Over-Heembeek, and Haren were incorporated into the municipality of Brussels, while Woluwe-Saint-Pierre (Sint-Pieters-Woluwe) became part of the bilingual agglomeration by law. After the language census of 1947, Evere, Ganshoren, and Sint-Agatha-Berchem were added to the bilingual agglomeration, although the implementation of this change was postponed until 1954 due to Flemish pressure. This was the last enlargement of the agglomeration, which brought the number of municipalities in Brussels to 19. In the peripheral municipalities of Kraainem, Linkebeek, Drogenbos, and Wemmel, where a French-speaking minority of more than 30% existed, language facilities were set up, although these municipalities officially remain in the Dutch language area.

| Year | Dutch | French |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 49.1% | 49.3% |

| 1920 | 39.2% | 60.5% |

| 1930 | 34.7% | 64.7% |

| 1947 | 25.5% | 74.2% |

The censuses on the use of languages in the municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region have shown that by 1947 French was becoming the most spoken language. However, in 1947, the percentage of residents declaring themselves bilingual was 45%, the percentage of monolingual Dutch speakers was 9% and the percentage of monolingual French speakers was 38%. In practice, bilingual citizens were most of the time bilingual Flemings. They were nevertheless recorded as bilinguals and not as Dutch speakers.

Establishment of the language border

See also: Language border and Municipalities with language facilities

Dutch language area French language area German language area

After both a Flemish boycott of the language census of 1960 and two large Flemish protest marches in Brussels, the language border was solidified in 1962 and the recently taken language census was annulled. Various municipalities shifted from one language area to another, such as Voeren, which became part of Flanders, and Comines-Warneton and Mouscron which became part of Wallonia. In both Wezembeek-Oppem and Sint-Genesius-Rode, language facilities were established for French speakers, who made up just under 30% of the population when the last language census in 1947 was taken. Brussels was fixed at 19 municipalities, thus creating a bilingual enclave in otherwise monolingual Flanders.

Brussels was limited to the current 19 municipalities. Many French speakers complained that this did not correspond to the social reality, since the language border was based on the results of the 1947 language census and not that of 1960. French-speaking sources claim that in that year, French-speaking minorities had surpassed the 30% threshold in Alsemberg, Beersel, Sint-Pieters-Leeuw, Dilbeek, Strombeek-Bever, Sterrebeek, and Sint-Stevens-Woluwe, in which case French-language facilities should have been established under previous legislation. A political rift developed because French speakers considered the language facilities as an essential right, while the Flemings saw the facilities as a temporary, transitional measure to allow the French-speaking minorities time to adapt to their Flemish surroundings.

The division of the country into language areas had serious consequences for education, and the "freedom of the head of household" was abolished. Thence, Dutch-speaking children were required to be educated in Dutch and French-speaking children in French. This stemmed the tide of further Francization of Brussels. Some of the more radical French speakers such as the Democratic Front of Francophones were opposed to this change and advocated the restoration of the freedom of education.

Criticism from the FDF

The Democratic Front of Francophones (French: Front démocratique des francophones, FDF) was founded in 1964 as a reaction to the fixation of the language border. The FDF decried the limitation of Brussels to 19 municipalities. They demanded free choice of language in the educational system, the freedom for the Brussels metropolitan area to grow beyond the language border and into the unilingual Flanders, and economic opportunities for the metropolitan area that would later comprise the Brussels-Capital Region. The Front accepted that governmental agencies in Brussels would be bilingual, but not that every civil servant working in those agencies be bilingual. The party experienced growing popularity and saw electoral success in the elections of the 1960s and 1970s.

The FDF objected to a fixed representation of the language groups in the agencies, considering this to be undemocratic. In the predecessor to the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region, for example, a significant number of seats were reserved for Dutch speakers. A number of French speakers circumvented this by claiming to be Dutch speakers, and over a third of the seats reserved for Dutch speakers were taken by these so-called "false Flemish".

With the fusion of Belgian municipalities in 1976, some primarily French-speaking municipalities joined larger municipalities with Flemish majorities, thereby reducing the number of French-speaking municipalities. Zellik joined Asse, Sint-Stevens-Woluwe and Sterrebeek joined Zaventem, and Strombeek-Bever joined Grimbergen. In addition, several larger municipalities with mostly Flemish populations were created, such as Sint-Pieters-Leeuw, Dilbeek, Beersel and Tervuren. The FDF saw this as a motive for the fusion of the municipalities, not a result of it.

Reassessment of Dutch

Amidst tension throughout the country, the sociolinguistic neglect of Dutch began to fade. The recognition of Dutch as the sole language of Flanders, the expansion of a well-functioning Flemish educational system, the development of the Flemish economy, and the popularization of Standard Dutch were responsible for its revitalization. The Flemish Community saw that if it wanted Dutch to have a prominent place in Brussels, it would need to make investing in Dutch language education its primary concern.

Integration of Dutch into the educational system

In 1971, the FDF managed to secure the right for individuals to again be able to choose the language of their education, and the FDF expected that Francization would continue as before. Initially, the effect was a reduction in the number of students enrolled in Flemish schools, falling from 6,000 students in elementary school and 16,000 in high school in 1966–1967 to 5,000 and 12,000 nine years later. But by that point, the Flemish Centre of Education, created in 1967, had begun its campaign to promote education in Dutch, with its initial target being Dutch-speaking families. In 1976, this task was taken up by the precursor to today's Flemish Community Commission (VGC), which made substantial investments to improve the quality of Dutch language schools. Starting in the 1978–1979 school year, the strategy began to bear fruit, and the number of children enrolled in Flemish daycares began to increase. This translated to an increase in enrollment in primary schools a few years later. As a result, all young Dutch-speaking children born after the mid-1970s have only gone to Flemish schools. The Francization of Dutch speakers became rarer with time. Nonetheless, foreign immigration continued to tilt the balance in favor of French.

In the 1980s, the VGC started concentrating its efforts on bilingual families, though the improvement of the Flemish schools had an unexpected effect; monolingual French-speaking families also began to send their children to Flemish schools. This effect increased bit by bit, as bilingualism began to be thought of as normal. Even today, the Flemish educational system continues to attract those with a first language other than Dutch; in 2005, 20% of students go to Dutch-speaking high schools, and for daycares, that figure reaches 23%. In fact, it has got to the point where those with Dutch as a first language are now a minority in the Flemish schools, and as a result, measures have needed to be taken to sustain the quality of education.

Socioeconomic development of Flanders

Wallonia's economic decline and the use of French by recent immigrants did little to help the prestige of French relative to Dutch. After World War II, the Flemish economy underwent significant growth. Flanders developed a prosperous middle class, and the prestige of Dutch saw an increase.

Those born into a monolingual Dutch family in Brussels had always had a lower level of education than the average for Brussels. By contrast, 30% of the Flemings who had moved to Brussels from elsewhere had a university degree or other post-secondary education, and were highly qualified. For example, since 1970 in Belgium as a whole, there have been more students enrolled in Dutch language universities than French ones. To be called a Dutch speaker no longer evokes images of lower-class laborers, as it long had. Bilingualism is increasingly a prerequisite for well-paying jobs, and what prestige the Dutch language currently has in Brussels is chiefly for economic reasons. The economic importance of Dutch in Brussels has little to do with the proportion of Brussels that is Dutch-speaking. Rather, it is primarily relations between businesses in Brussels and Flemish businesses, or more generally, with Dutch-speaking businesses as a whole that ensure the economic importance of Dutch in Brussels.

Foreign immigration

See also: Brussels and the European UnionIn 1958, Brussels became the seat of the European Economic Community, which later became the EU, while the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was resettled in Belgium in 1967 with its headquarters in Evere. This, combined with economic immigration from southern Europe and later from Turkey, Morocco (a former French protectorate), and Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Belgian Congo), changed the makeup of the population of Brussels. Between 1961 and 2006, the number of non-Belgian inhabitants grew from 7% to 56%. The newcomers adopted and spoke French in great numbers, mainly due to the French-speaking African origins of many that came, with many Moroccans and Congolese already possessing proficiency in French at the time of their arrival.

In general, foreign immigration further reduced the percentage of Dutch speakers and led to the city's further Francization. This stood in contrast to the 20th century's first half, however, when the change was the Francization of Brussels's existing Flemish inhabitants.

Francization of immigrants and expatriates

Out of all immigrant groups, Moroccan immigrants in Belgium used French the most, which gained increasing importance alongside Berber and Moroccan Arabic in their already bilingual community. The Turks held on to their own language, although French also gained importance in their community. Dutch struggled to take hold in these two migrant groups. Children from these communities attended (and often continue to attend) French-language education, and used French in their circles of friends and at home. This evolution is also seen with Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian migrants, who easily adopted French due to its similarity to other Romance languages that many already spoke. The northern Europeans, who are not nearly as numerous and came mainly after the 1980s, make more use of their own languages, such as English and German. When these northern Europeans married French speakers, the language spoken at home often became French. In these groups, the long-term effects and trends of language shift are difficult to determine.

Brussels' multicultural and multiethnic character has widened the language situation beyond merely considering Dutch and French. Dutch is patently less well represented than French in the monolingual population. Out of 74 selected Dutch speakers, only two were found to be monolingual, approximately nine times fewer than in the French-speaking population. Out of the inhabitants of Brussels-Capital region with foreign nationality, in 2000, 3% spoke exclusively Dutch at home, compared to 9% who spoke exclusively French. In addition, 16% spoke another language in addition to French at home.

Japanese people residing in Brussels generally encounter the French language at work. All of the schooling options for Japanese national children provide French education, and Marie Conte-Helm, author of The Japanese and Europe, wrote that "French language education thus becomes, to a greater or a lesser degree, a normal part" of the everyday lives in Japanese expatriates.

Creation of the Brussels-Capital Region

The 19 municipalities of Brussels are the only officially bilingual part of Belgium. The creation of a bilingual, full-fledged Brussels region, with its own competencies and jurisdiction, had long been hampered by different visions of Belgian federalism. Initially, Flemish political parties demanded Flanders be given jurisdiction over cultural matters, concerned with the dominance of the French language in the federal government. Likewise, as Wallonia was in economic decline, Francophone political parties were concerned with getting economic autonomy for the French-speaking regions to address the situation. The Flemings also feared being in the minority, faced with two other French-speaking regions. They viewed the creation of a separate Brussels region as definitively cutting Brussels off from Flanders, an admission of the loss of Brussels to Francization.

Periphery of Brussels

In Drogenbos, Kraainem, Linkebeek, Sint-Genesius-Rode, Wemmel and Wezembeek-Oppem, the six municipalities with language facilities in the suburbs around Brussels, the proportion of the population that was French-speaking also grew in the second half of the 20th century, and they now constitute a majority. In the administrative arrondissement of Halle-Vilvoorde, which constitutes those six municipalities and 29 other Flemish municipalities, around 25% of families speak French at home. The Flemish government sees this as a worrying trend, and enacted policies designed to keep the periphery of Brussels Dutch-speaking. One effect of this policy was a very literal interpretation of the linguistic facility laws, including the Peeters directive. This circulaire stipulates, among other things, that when French speakers in those six municipalities with language facilities deal with the government, they can request a French version of documents or publications but need to do so every time they want one; the government is not allowed to register their preference.

Current situation

French only Dutch and French Dutch only French and other language Neither Dutch nor French

In Brussels's northwestern municipalities, the proportion of Dutch speakers is high compared to other municipalities in Brussels. It is in these same municipalities that the proportion of non-native Dutch speakers who speak Dutch is highest, generally in excess of 20%. At the two extremes are Ganshoren, where 25% of non-native speakers speak Dutch, and Saint-Gilles, where Dutch as a language spoken at home has practically disappeared.

The younger a generation is, the poorer its knowledge of Dutch tends to be. The demographic of those who grew up speaking only Dutch at home, and to a lesser extent those who grew up bilingual, is significantly older than the Brussels average. Between 2000 and 2006, the proportion of monolingual Dutch families shrank from 9.5% to 7.0%, whereas bilingual families shrank from 9.9% to 8.6%. On the other hand, in the same period the number of non-native Dutch speakers with a good-to-excellent knowledge of Dutch saw an increase. Half of those in Brussels with a good knowledge of Dutch learned the language outside of their family, and this figure is expected to increase. In 2001, 70% of the city had a knowledge of Dutch that was "at least passable". In 2006, 28% of those living in Brussels had a good to excellent knowledge of Dutch, while 96% had a good to excellent knowledge of French, and 35% of English. French was found to be spoken at home in 77% of households in Brussels, Dutch in 6% of households, and neither official language was spoken in 16% of households. French is thus by far the best-known language in Brussels and remains the city's lingua franca.

Of businesses based in Brussels, 50% use French for internal business, while 32% use French and Dutch, the others using a variety of other languages. More than a third of job openings require bilingualism, and a fifth of job openings require knowledge of English. On account of this, it is argued that an increase in knowledge of Dutch in Brussels and Wallonia would significantly improve the prospects of job seekers in those regions. Of advertising campaigns in Brussels, 42% are bilingual French and Dutch, while 33% are in French only, 10% in French and English and 7% in English, French and Dutch. During the day, the percentage of Dutch-speakers in Brussels increases significantly, with 230,000 commuters coming from the Flemish Region, significantly more than the 130,000 coming from the Walloon Region.

National political concerns

Francophones living in Flanders want Flanders to ratify the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, which has been signed by almost every country in Europe, though in Belgium, it has been signed but not ratified (also the case in a handful of others). The Framework would allow Francophones to claim the right to use their own language when dealing with the authorities, bilingual street names, schooling in French, etc. The Framework, however, does not specify what a "National Minority" is, and the Flemings do not see the Francophones in Flanders as being one. Flanders is not inclined to approve the Framework, in spite of frequent appeals by the Council of Europe to do so.

In Flemish circles, there is an ever-continuing worry that the status of Dutch in Brussels will continue to deteriorate and that the surrounding region will undergo even more Francization. On the political level, the division of the bilingual Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde (BHV) electoral and judicial district caused much linguistic strife. The district is composed of the 19 municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region in addition to the 35 municipalities of the Flemish administrative arrondissement of Halle-Vilvoorde. For elections to the Belgian Senate and to the European Parliament, which are organized by linguistic region, residents from anywhere in the arrondissement can vote for French-speaking parties in Wallonia and Brussels. For elections to the Belgian Chamber of Representatives, which is usually done by province, voters from Halle-Vilvoorde can vote for parties in Brussels, and vice versa. It was feared that, if BHV was divided, the Francophones living in Halle-Vilvoorde would no longer be able to vote for candidates in Brussels, and they would lose the right to judicial proceedings in French. If a division were to take place, Francophone political parties would demand that the Brussels-Capital Region be expanded, a proposal that is unacceptable to Flemish parties. This issue was one of the chief reasons for the 200-day impasse in Belgian government formation in 2007, and it remained a hotly contested issue among the linguistic Communities until this issue was resolved mid-2012.

See also

References

- ^ Backhaus, Peter (2007). Linguistic Landscapes: A Comparative Study of Urban Multilingualism in Tokyo. Multilingual Matters Ltd. p. 158. ISBN 9781853599460. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Janssens, Guy (2005). Het Nederlands vroeger en nu (in Dutch). ACCO. ISBN 9033457822. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Jaumain, Serge (2006). Vivre en Ville: Bruxelles et Montréal aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French) (Études Canadiennes Series nº9 ed.). Peter Lang. p. 375. ISBN 9789052013343. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Roegiest, Eugeen (2009). Vers les sources des langues romanes. Un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania (in French). ACCO. p. 272. ISBN 9789033473807. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Janssens, Rudi (2008). Taalgebruik in Brussel en de plaats van het Nederlands — Enkele recente bevindingen (PDF) (in Dutch) (Brussels Studies, nº13 ed.). Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Kramer, Johannes (1984). Zweisprachigkeit in den Benelux-ländern. Buske Verlag. ISBN 3871185973. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Baetens Beardsmore, Hugo (1986). Bilingualism: Basic Principles (2nd Ed.) (Multiligual Matters Series ed.). Multilingual Matters Ltd. p. 205. ISBN 9780905028637. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Ernst, Gerhard (2006). Histoire des langues romanes (in French) (Manuel international sur l'histoire et l'étude linguistique des langues romanes ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 1166. ISBN 9783110171501. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Vermeersch, Arthur J. (1981). De taalsituatie tijdens het Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden (1814–1830) (PDF) (in Dutch) (Taal en Sociale Integratie, IV ed.). Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). pp. 389–404. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Poirier, Johanne (1999). Choix, statut et mission d'une capitale fédérale: Bruxelles au regard du droit comparé (in French) (Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut ed.). Brussel: De Boeck & Larcier. p. 817. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- Rousseaux, Xavier (1997). Le pénal dans tous ses états: justice, États et sociétés en Europe (in French) (Volume 74 ed.). Publications des Fac. St Louis. p. 462. ISBN 9782802801153. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Wils, Lode (2005). Van Clovis tot Di Rupo: de lange weg van de naties in de Lage Landen (in Dutch) (Reeks Historama (nummer 1) ed.). Garant. p. 297. ISBN 9789044117387. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Blampain, Daniel (1997). Le français en Belgique: Une communauté, une langue (in French). De Boeck Université. ISBN 2801111260. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ De Groof, Roel (2003). De kwestie Groot-Brussel en de politieke metropolisering van de hoofdstad (1830–1940). Een analyse van de besluitvorming en de politiek-institutionele aspecten van de voorstellen tot hereniging, annexatie, fusie, federatie en districtvorming van Brussel en zijn voorsteden (in Dutch) (De Brusselse negentien gemeenten en het Brussels model / Les dix-neuf communes bruxelloises et le modèle bruxellois ed.). Brussel, Gent: De Boeck & Larcier. p. 754. ISBN 2-8044-1216-4.

- ^ Gubin, Eliane (1978). La situation des langues à Bruxelles au 19ième siècle à la lumière d'un examen critique des statistiques (PDF) (in French) (Taal en Sociale Integratie, I ed.). Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB). pp. 33–80. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Witte, Els (1998). Taal en politiek: De Belgische casus in een historisch perspectief (PDF) (in Dutch) (Balansreeks ed.). Brussel: VUBPress (Vrije Universiteit Brussel). p. 180. ISBN 9789054871774.

- Von Busekist, Astrid (2002). Nationalisme contre bilinguisme: le cas belge (in French) (La Politique de Babel: du monolinguisme d'État au plurilinguisme des peuples ed.). Éditions KARTHALA. p. 348. ISBN 9782845862401. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Bitsch, Marie-Thérèse (2004). Histoire de la Belgique: De l'Antiquité à nos jours (in French). Éditions Complexe. p. 299. ISBN 9782804800239. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Tétart, Frank (2009). Nationalismes régionaux: Un défi pour l'Europe (in French). De Boeck Supérieur. p. 112. ISBN 9782804117818. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Kok Escalle, Marie-Christine (2001). Changements politiques et statut des langues: histoire et épistémologie 1780-1945 (in French) (Faux Titre (volume 206) ed.). Rodopi. p. 374. ISBN 9789042013759. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Bogaert-Damin, Anne Marie (1978). Bruxelles: développement de l'ensemble urbain 1846–1961 (in French). Presses universitaires de Namur. p. 337. ISBN 9782870370896. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Hasquin, Hervé (1996). Bruxelles, ville frontière. Le point de vue d'un historien francophone (in French) (Europe et ses ville-frontières ed.). Bruxelles: Éditions Complexe. p. 329. ISBN 9782870276631. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Vrints, Antoon (2011). Het theater van de Straat: Publiek geweld in Antwerpen tijdens de eerste helft van de twintigste Eeuw (in Dutch) (Studies Stadsgeschiedenis Series ed.). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-9089643407. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Capron, Catherine (2000). La dualité démographique de la Belgique : mythe ou réalité? (in French) (Régimes démographiques et territoires: les frontières en question ed.). INED. ISBN 2950935680. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- van Velthoven, Harry (1981). Taal- en onderwijspolitiek te Brussel (1878-1914) (PDF) (in Dutch) (Taal en Sociale Integratie, IV ed.). Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). pp. 261–387. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Witte, Els (1999). Analyse du statut de Bruxelles (1989–1999) (in French) (Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut ed.). Brussel: De Boeck & Larcier. p. 817. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- ^ Treffers-Daller, Jeanine (1994). Mixing Two Languages: French-Dutch Contact in a Comparative Perspective. Walter de Gruyter. p. 300. ISBN 3110138379. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- de Metsenaere, Machteld (1990). Thuis in gescheiden werelden — De migratoire en sociale aspecten van verfransing te Brussel in het midden van de 19e eeuw (PDF) (in Dutch) (BTNG-RBHC, XXI, 1990, nº 3–4 ed.). Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Mares, Ann (2001). Begin van het einde van de nationale partijen. Onderzoek naar de Vlaamse Beweging(en) en de Vlaamse politieke partijen in Brussel: de Rode Leeuwen (PDF) (in Dutch) (19 keer Brussel; Brusselse Thema's (7) ed.). VUBPress (Vrije Universiteit Brussel). ISBN 9054872926. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Depré, Leen (2001). Tien jaar persberichtgeving over de faciliteitenproblematiek in de Brusselse Rand. Een inhoudsanalystisch onderzoek (PDF) (in Dutch) (19 keer Brussel; Brusselse Thema's (7) ed.). VUBPress (Vrije Universiteit Brussel). p. 281. ISBN 9054872926. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Janssens, Rudi (2001). Over Brusselse Vlamingen en het Nederlands in Brussel (PDF) (in Dutch) (19 keer Brussel; Brusselse Thema's (7) ed.). VUBPress (Vrije Universiteit Brussel). p. 60. ISBN 9054872926. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Detant, Anja (1999). Kunnen taalvrijheid en officiële tweetaligheid verzoend worden? De toepassing van de taalwetgeving in het Brussels Hoofdstedelijke Gewest en de 19 gemeenten (in Dutch) (Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut ed.). Brussel: De Boeck & Larcier. p. 817. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- ^ Witte, Els (2006). De Geschiedenis van België na 1945 (in Dutch). Antwerpen: Standaard Uitgeverij. p. 576. ISBN 9789002219634.

- Klinkenberg, Jean-Marie (1999). Des langues romanes: Introduction aux études de linguistique romane (in French) (Champs linguistiques ed.). De Boeck Supérieur. p. 316. ISBN 9782801112274. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Kesteloot, Chantal (2004). Au nom de la Wallonie et de Bruxelles français: Les origines du FDF (in French) (Histoires contemporaines ed.). Éditions Complexe. p. 375. ISBN 9782870279878. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Frognier, André-Paul (1999). Les interactions stratégiques dans la problématique communautaire et la question bruxelloise (in French) (Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut ed.). Brussel: De Boeck & Larcier. p. 817. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- ^ Paul De Ridder. "De mythe van de vroege verfransing — Taalgebruik te Brussel van de 12de eeuw tot 1794" (PDF) (in Dutch). Paul De Ridder. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Robert Sixte (6 December 1963). "Bruxelles, la Flandre, et le fédéralisme". La Gauche n°47 (in French). Ernest Mandel – Archives internet. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Guy Janssens; Ann Marynissen (2005). Het Nederlands vroeger en nu (in Dutch). ACCO. ISBN 90-334-5782-2. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Daniel Droixhe (13 April 2002). "Le français en Wallonnie et à Bruxelles aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles" (in French). Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB). Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ "Vlaanderen tot 1914". Nederlands Online (neon) (in Dutch). Free University of Berlin (FU Berlin). 27 June 2004. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Ernest Mandel; Jacques Yerna (19 April 1958). "Perspectives socialistes sur la question flamande". La Gauche n°16 (in French). Ernest Mandel – Archives internet. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

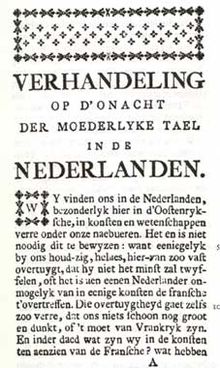

- Original title: Verhandeling op d’onacht der moederlyke tael in de Nederlanden

- ^ Thomas De Wolf (2003–2004). "De visie van reizigers op Brabant en Mechelen (1701–1800)". Licentiaatsverhandelingen on-line (in Dutch). Ghent University. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ "Het Nederlands in Brussel". Geschiedenis van het Nederlands (in Dutch). NEDWEB — University of Vienna. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Jacques Leclerc (associated member of the Trésor de la langue française au Québec) (9 November 2008). "Petite histoire de la Belgique et ses conséquences linguistiques". L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde (in French). Université Laval. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ G. Geerts; M.C. van den Toorn; W. Pijnenburg; J.A. van Leuvensteijn; J.M. van der Horst (1997). "Nederlands in België, Het Nederlands bedreigd en overlevend". Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse taal (in Dutch). Amsterdam University Press (University of Amsterdam). ISBN 90-5356-234-6. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- Alexander Ganse. "Belgium under French Administration, 1795–1799". Korean Minjok Leadership Academy. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ^ Daniel Suy (1997). "De Franse overheersing (1792 – 1794 – 1815)". De geschiedenis van Brussel (in Dutch). Flemish Community Commission (VGC). Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- "Broeksele". Bruisend Brussel (in Dutch). University College London (UCL). 2006. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- Jacques Leclerc (associated member of the Trésor de la langue française au Québec). "Belgique – België – Belgien" (in French). Université Laval. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- Alexander Ganse. "The Flemish Peasants War of 1798". Korean Minjok Leadership Academy. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ Eliane Gubin (1978). "La situation des langues à Bruxelles au XIXe siècle à la lumière d'un examen critique des statistiques" (PDF). Taal en Sociale Integratie, I (in French). Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB). pp. 33–80. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Paul De Ridder (1979). "Peilingen naar het taalgebruik in Brusselse stadscartularia en stadsrekeningen (XIIIde-XVde eeuw)" (PDF). Taal en Sociale Integratie, II (in Dutch). Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). pp. 1–39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Johan Winkler (1874). "De stad Brussel". Algemeen Nederduitsch en Friesch Dialecticon (in Dutch). Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren. pp. 264–272. Archived from the original on 7 January 2005. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Junius Julien (1991). "De territoriale groei van Brussel". Brussels Onderwijspunt (in Dutch). Flemish Community Commission (VGC). Archived from the original on 23 July 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- "Het Nederlands: status en verspreiding". Nederlands Online (neon) (in Dutch). Free University of Berlin (FU Berlin). 18 June 2004. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Robert Demoulin. "La langue et la révolution de 1830". Unification politique, essor économique (1794–1914) — Histoire de la Wallonie (in French). Wallonie en mouvement. pp. 313–322. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Marcel Bauwens (1998–2005). "Comment sortir du labyrinthe belge ?". Nouvelles de Flandre (in French). Association pour la Promotion de Francophonie en Flandre (APFF). Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ "Brussel historisch". Hoofdstedelijke Aangelegenheden (in Dutch). Ministry of the Flemish Community. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Flanders Online. "Brussel verfranst in de 19 eeuw" (in Dutch). Vlaams Dienstencentrum vzw. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- Jan Erk (2002). "Le Québec entre la Flandre et la Wallonie : Une comparaison des nationalismes sous-étatiques belges et du nationalisme québécois". Recherches Sociographiques (in French). 43 (3). Université Laval: 499–516. doi:10.7202/000609ar. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ "De sociale taalgrens". Als goede buren: Vlaanderen en de taalwetgeving (in Dutch). Ministry of the Flemish Community. 1999. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Rudi Janssens (2001). Taalgebruik in Brussel — Taalverhoudingen, taalverschuivingen en taalidentiteit in een meertalige stad (PDF) (in Dutch). VUBPress (Vrije Universiteit Brussel, VUB). ISBN 90-5487-293-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Original quote: On ne sait pas le français, personne ne le sait, mais tout le monde affecte de ne pas connaître le flamand. C’est de bon goût. La preuve qu’ils le savent très bien, c’est qu’ils engueulent leurs domestiques en flamand.

- ^ Harry van Velthoven (1981). "Taal- en onderwijspolitiek te Brussel (1878–1914)" (PDF). Taal en Sociale Integratie, IV (in Dutch). Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). pp. 261–387. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- "Geschiedenis van de Vlaamse Beweging". Cultuurkunde van België (in Dutch). NEDWEB — University of Vienna. Archived from the original on 18 April 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ "Over het Brussels Nederlandstalig onderwijs" (in Dutch). Flemish Community Commission (VGC). Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Machteld de Metsenaere (1990). "Thuis in gescheiden werelden — De migratoire en sociale aspecten van verfransing te Brussel in het midden van de 19e eeuw" (PDF). BTNG-RBHC, XXI, 1990, n° 3–4 (in Dutch). Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- UVV Info (2005). "Dossier "150 jaar Vlaamse studenten in Brussel"" (PDF) (in Dutch). Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ G. Geerts. "De taalpolitieke ontwikkelingen in België". Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse taal (in Dutch). M.C. van den Toorn, W. Pijnenburg, J.A. van Leuvensteijn and J.M. van der Horst.

- "Een eeuw taalwetten". Als goede buren: Vlaanderen en de taalwetgeving (in Dutch). Ministry of the Flemish Community. 1999. Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Liesbet Vandersteene (3 January 2006). "De Universiteit in de kering 1876–1930". Geschiedenis van de faculteit Rechtsgeleerdheid (in Dutch). Ghent University. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Luc Van Braekel (2003). "Tweede en derde taalwet" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 3 January 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Johan Slembrouck (2 August 2007). "Sint-Stevens-Woluwe: een unicum in de Belgische geschiedenis" (in Dutch). Overlegcentrum van Vlaamse Verenigingen (OVV). Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ "Histoire des discriminations linguistiques ou pour motifs linguistiques, contre les francophones de la périphérie bruxelloise (de 120.000 à 150.000 citoyens belges)". Histoire (in French). Carrefour. 8 November 2007. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- "Frontière linguistique, frontière politique" (in French). Wallonie en mouvement. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ "De Belgische troebelen" (in Dutch). Knack. 12 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- Paul Tourret (2001). "La " tyrannie flamingante " vue par les francophones". Affiches publiées par la « Ligue contre la flamandisation de Bruxelles » (in French). Université Laval. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ Edwin Smellinckx (2000–2001). "Urbanisme in Brussel, 1830–1860". Licentiaatsverhandelingen on-line (in Dutch). Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (KULeuven). Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Stefaan Huysentruyt; Mark Deweerdt (29 December 2004). "Raad van State beperkt toepassing faciliteiten in randgemeenten" (PDF) (in Dutch). De Tijd. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- Jacques Leclerc (associated member of the Trésor de la langue française au Québec) (30 September 2008). "La Communauté flamande de Belgique". L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde (in French). Université Laval. Archived from the original on 18 January 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Paul Debongnie (30 April 1981). "L'historique du FDF" (in French). Front démocratique des francophones (FDF). Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Kris Deschouwer; Jo Buelens (1999). Het statuut van de Brusselse gemeenten: denkpistes voor een mogelijke hervorming in Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut (in Dutch). Brussels: De Boeck & Larcier. pp. 439–463. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- (in French) La Communauté française de Belgique Archived 2009-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, Département de Langues, linguistique et traduction, Faculté des Lettres, Université Laval de Québec, Canada

- (in French) Les francophones de la périphérie, Baudouin Peeters, La Tribune de Bruxelles

- ^ Jan Hertogen (4 April 2007). "Laatste 45 jaar in Brussel: 50% bevolking van autochtoon naar allochtoon". Bericht uit het Gewisse (in Dutch). Non-Profit Data. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Helder De Schutter (2001). "Taalpolitiek en multiculturalisme in het Brussels Nederlandstalig onderwijs" [Language policy and multiculturalism in Dutch-speaking education in Brussels]. In Ann Mares; Els Witte (eds.). 19 keer Brussel; Brusselse Thema's 7 [19 times Brussels: Brussels Themes 7] (PDF) (in Dutch, French, and English). VUBPress. pp. 375–421. ISBN 90-5487-292-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- Jan Velaers (1999). Vlaanderen laat Brussel niet los": de Vlaamse invulling van de gemeenschapsautonomie in het tweetalige gebied Brussel-Hoofdstad in Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut (in Dutch). Brussels: De Boeck & Larcier. pp. 595–625. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- ^ Jean-Paul Nassaux (9 November 2007). "Bruxelles, un enjeu pour la francophonie" (in French). Libération. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- Roel Jacobs; Bernard Desmet (19 March 2008). "Bruxelles, plus que bilingue ! Une richesse ou un problème ?". DiverCity (in French). Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- University College London, ed. (2006). "Wereldcentrum in het hart van Europa". Bruisend Brussel (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 23 July 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- Eric Corijn (12 November 2007). "Bruxelles n'est pas le problème, c'est la solution" (in French). Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). Retrieved 17 January 2009. Toegankelijk via Indymedia.

- Marc Philippe, representing RWF-RBF (23 October 2003). "La si longue histoire du conflit linguistique à Bruxelles" (in French). Vox Latina. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Conte-Helm, Marie. The Japanese and Europe: Economic and Cultural Encounters (Bloomsbury Academic Collections). A&C Black, 17 December 2013. ISBN 1780939809, 9781780939803. p. 105.

- "Verfransing gevolg van stadsvlucht" (in Dutch). Het Volk. 24 May 2007. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- "La Constitution belge (Art. 4)" (in French). the Belgian Senate. May 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

La Belgique comprend quatre régions linguistiques : la région de langue française, la région de langue néerlandaise, la région bilingue de Bruxelles-Capitale et la région de langue allemande.

. - Dirk Jacobs (1999). De toekomst van Brussel als meertalige en multiculturele stad. Hebt u al een partijstandpunt? in Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut (in Dutch). Brussels: De Boeck & Larcier. pp. 661–703. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- Philippe De Bruycker (1999). Le défi de l'unité bruxelloise in Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut (in French). Brussels: De Boeck & Larcier. pp. 465–472. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- Crisp (Centre de recherche et d'information socio-politiques). "La naissance de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale". Présentation de la Région (in French). Brussels-Capital Region. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- "Sociaal-economisch profiel van de Vlaamse Rand en een blik op het Vlaamse karakter" (doc) (in Dutch). Government of the Flemish Community. 23 March 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- "Decreet houdende oprichting van de v.z.w. "de Rand" voor de ondersteuning van het Nederlandstalige karakter van de Vlaamse rand rond Brussel" (PDF) (in Dutch). Flemish Parliament. 27 November 1996. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- "Betreft: Omzendbrief BA 97/22 van 16 december 1997 betreffende het taalgebruik in gemeentebesturen van het Nederlandse taalgebied (Peeters directive)" (in Dutch). Government of the Flemish Community. 16 December 1997. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Janssens, Rudi (2013). BRIO-taalbarometer 3: diversiteit als norm (PDF) (in Dutch) (Brussels Informatie-, Documentatie- en Onderzoekscentrum ed.). Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- "Pour une réforme des institutions belges qui combine flexibilité et coordination" (PDF) (in French). Centre Interuniversitaire de Formation Permanente (C.I.Fo.P.). 26 January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- "Pendelarbeid tussen de gewesten en provincies in België anno 2006". Vlaamse statistieken, strategisch management en surveyonderzoek (in Dutch). FPS Economy Belgium. 2007. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Xavier Delgrange; Ann Mares; Petra Meier (2003). La représentation flamande dans les communes bruxelloises in Les dix-neuf communes bruxelloises et le modèle bruxellois (in French). Brussels, Ghent: De Boeck & Larcier. pp. 311–340. ISBN 2-8044-1216-4.

- Jan Clement; Xavier Delgrange (1999). La protection des minorités - De bescherming van de minderheden in Het statuut van Brussel / Bruxelles et son statut (in French). Brussels: De Boeck & Larcier. pp. 517–555. ISBN 2-8044-0525-7.

- Theo L.R. Lansloot (2001). "Vlaanderen versus de Raad van Europa" (PDF). Secessie (in Dutch). Mia Brans Instituut. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Steven Samyn (20 April 2004). "Wat u moet weten over Brussel-Halle-Vilvoorde" (in Dutch). De Standaard. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- M.Bu. (6 September 2007). "BHV : c'est quoi ce truc ?" (in French). La Libre Belgique. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

Further reading

- Schaepdrijver, Sophie de (1990). Elites for the Capital?: Foreign Migration to mid-nineteenth-century Brussels. Amsterdam: Thesis Publishers. ISBN 9789051700688.

| Cultural assimilation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Opposite trends | |||||

| Related concepts | |||||