Curling games taking place during the 2005 Tim Hortons Brier Curling games taking place during the 2005 Tim Hortons Brier | |

| Highest governing body | World Curling Federation |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Chess On Ice, The Roaring Game |

| First played | Approximately late medieval Scotland |

| Registered players | est. 1.5 million |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Team members | 4 per team (2 in doubles) |

| Mixed-sex | Yes; see mixed curling |

| Type | Precision and accuracy |

| Equipment | Curling brooms, stones (rocks), curling shoes |

| Venue | Curling sheet |

| Glossary | Glossary of curling |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | |

| Paralympic | Wheelchair curling officially added in 2006 |

Curling is a sport in which players slide stones on a sheet of ice toward a target area that is segmented into four concentric circles. It is related to bowls, boules, and shuffleboard. Two teams, each with four players, take turns sliding heavy, polished granite stones, also called rocks, across the ice curling sheet toward the house, a circular target marked on the ice. Each team has eight stones, with each player throwing two. The purpose is to accumulate the highest score for a game; points are scored for the stones resting closest to the centre of the house at the conclusion of each end, which is completed when both teams have thrown all of their stones once. A game usually consists of eight or ten ends.

Players induce a curved path, described as curl, by causing the stone to slowly rotate as it slides. The path of the rock may be further influenced by two sweepers with brooms or brushes, who accompany it as it slides down the sheet and sweep the ice in front of the stone. "Sweeping a rock" decreases the friction, which makes the stone travel a straighter path (with less curl) and a longer distance. A great deal of strategy and teamwork go into choosing the ideal path and placement of a stone for each situation, and the skills of the curlers determine the degree to which the stone will achieve the desired result.

History

Evidence that curling existed in Scotland in the early 16th century includes a curling stone inscribed with the date 1511 found (along with another bearing the date 1551) when an old pond was drained at Dunblane, Scotland. The world's oldest curling stone and the world's oldest football are now kept in the same museum (the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum) in Stirling. The first written reference to a contest using stones on ice coming from the records of Paisley Abbey, Renfrewshire, in February 1541. Two paintings, "Winter Landscape with a Bird Trap" and "The Hunters in the Snow" (both dated 1565) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, depict Flemish peasants curling, albeit without brooms; Scotland and the Low Countries had strong trading and cultural links during this period, which is also evident in the history of golf.

The word curling first appears in print in 1620 in Perth, Scotland, in the preface and the verses of a poem by Henry Adamson. The sport was (and still is, in Scotland and Scottish-settled regions like southern New Zealand) also known as "the roaring game" because of the sound the stones make while traveling over the pebble (droplets of water applied to the playing surface). The verbal noun curling is formed from the Scots (and English) verb curl, which describes the motion of the stone.

Kilsyth Curling Club claims to be the first club in the world, having been formally constituted in 1716; it is still in existence today. Kilsyth also claims the oldest purpose-built curling pond in the world at Colzium, in the form of a low dam creating a shallow pool some 100 by 250 metres (330 by 820 ft) in size. The International Olympic Committee recognises the Royal Caledonian Curling Club (founded as the Grand Caledonian Curling Club in 1838) as developing the first official rules for the sport. However, although not written as a "rule book", this is preceded by Rev James Ramsay of Gladsmuir, a member of the Duddingston Curling Club, who wrote An Account of the Game of Curling in 1811, which speculates on its origin and explains the method of play.

In the early history of curling, the playing stones were simply flat-bottomed stones from rivers or fields, which lacked a handle and were of inconsistent size, shape, and smoothness. Some early stones had holes for a finger and the thumb, akin to ten-pin bowling balls. Unlike today, the thrower had little control over the 'curl' or velocity and relied more on luck than on precision, skill, and strategy. The sport was often played on frozen rivers although purpose-built ponds were later created in many Scottish towns. For example, the Scottish poet David Gray describes whisky-drinking curlers on the Luggie Water at Kirkintilloch.

In Darvel, East Ayrshire, the weavers relaxed by playing curling matches using the heavy stone weights from the looms' warp beams, fitted with a detachable handle for the purpose. Central Canadian curlers often used 'irons' rather than stones until the early 1900s; Canada is the only country known to have done so, while others experimented with wood or ice-filled tins.

Outdoor curling was very popular in Scotland between the 16th and 19th centuries because the climate provided good ice conditions every winter. Scotland is home to the international governing body for curling, the World Curling Federation in Perth, which originated as a committee of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club, the mother club of curling.

In the 19th century, several private railway stations in the United Kingdom were built to serve curlers attending bonspiels, such as those at Aboyne, Carsbreck, and Drummuir.

Today, the sport is most firmly established in Canada, having been taken there by Scottish emigrants. The Royal Montreal Curling Club, the oldest established sports club still active in North America, was established in 1807. The first curling club in the United States was established in 1830, and the sport was introduced to Switzerland and Sweden before the end of the 19th century, also by Scots. Today, curling is played all over Europe and has spread to Brazil, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, China, and Korea.

The first world championship for curling was limited to men and was known as the Scotch Cup, held in Falkirk and Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1959. The first world title was won by the Canadian team from Regina, Saskatchewan, skipped by Ernie Richardson. (The skip is the team member who calls the shots; see below.)

Olympics

Main article: Curling at the Winter Olympics

Curling has been a medal sport in the Winter Olympic Games since the 1998 Winter Olympics. It currently includes men's, women's, and mixed doubles tournaments (the mixed doubles event was held for the first time in 2018).

In February 2002, the International Olympic Committee retroactively decided that the curling competition from the 1924 Winter Olympics (originally called Semaine des Sports d'Hiver, or International Winter Sports Week) would be considered official Olympic events and no longer be considered demonstration events. Thus, the first Olympic medals in curling, which at the time was played outdoors, were retroactively awarded for the 1924 Winter Games, with the gold medal won by Great Britain, two silver medals by Sweden, and the bronze by France. A demonstration tournament was also held during the 1932 Winter Olympic Games between four teams from Canada and four from the United States, with Canada winning 12 games to 4.

Since the sport's official addition in the 1998 Olympics, Canada has dominated the sport with their men's teams winning gold in 2006, 2010, and 2014, and silver in 1998 and 2002. The women's team won gold in 1998 and 2014, a silver in 2010, and a bronze in 2002 and 2006. The mixed doubles team won gold in 2018.

Equipment

Curling sheet

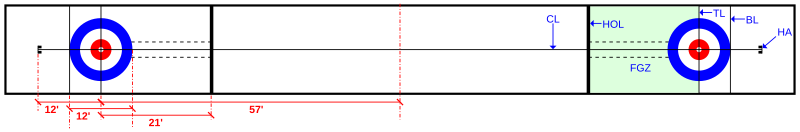

The playing surface or curling sheet is defined by the World Curling Federation Rules of Curling. It is a rectangular area of ice, carefully prepared to be as flat and level as possible, 146 to 150 feet (45 to 46 m) in length by 14.5 to 16.5 feet (4.4 to 5.0 m) in width. The shorter borders of the sheet are called the backboards.

A target, the house, is centred on the intersection of the centre line, drawn lengthwise down the centre of the sheet and the tee line, drawn 16 feet (4.9 m) from, and parallel to, the backboard. These lines divide the house into quarters. The house consists of a centre circle (the button) and three concentric rings, of diameters 4, 8, and 12 feet, formed by painting or laying a coloured vinyl sheet under the ice and are usually distinguished by colour. A stone must at least touch the outer ring in order to score (see Scoring below); otherwise, the rings are merely a visual aid for aiming and judging which stone is closer to the button. Two hog lines are drawn 37 feet (11 m) from, and parallel to, the backboard.

The hacks, which give the thrower something to push against when making the throw, are fixed 12 feet (3.7 m) behind each button. On indoor rinks, there are usually two fixed hacks, rubber-lined holes, one on each side of the centre line, with the inside edge no more than 3 inches (76 mm) from the centre line and the front edge on the hack line. A single moveable hack may also be used.

The ice may be natural, but is usually frozen by a refrigeration plant pumping a brine solution through numerous pipes fixed lengthwise at the bottom of a shallow pan of water. Most curling clubs have an ice maker whose main job is to care for the ice. At the major curling championships, ice maintenance is extremely important. Large events, such as national/international championships, are typically held in an arena that presents a challenge to the ice maker, who must constantly monitor and adjust the ice and air temperatures as well as air humidity levels to ensure a consistent playing surface. It is common for each sheet of ice to have multiple sensors embedded in order to monitor surface temperature, as well as probes set up in the seating area (to monitor humidity) and in the compressor room (to monitor brine supply and return temperatures). The surface of the ice is maintained at a temperature of around 23 °F (−5 °C).

A key part of the preparation of the playing surface is the spraying of water droplets onto the ice, which form pebble on freezing. The pebbled ice surface resembles an orange peel, and the stone moves on top of the pebbled ice. The pebble, along with the concave bottom of the stone, decreases the friction between the stone and the ice, allowing the stone to travel further. As the stone moves over the pebble, any rotation of the stone causes it to curl, or travel along a curved path. The amount of curl (commonly referred to as the feet of curl) can change during a game as the pebble wears; the ice maker must monitor this and be prepared to scrape and re-pebble the surface prior to each game.

A curling sheet, with dimensions in feet (1' = 1 ft = 0.3 m).

A curling sheet, with dimensions in feet (1' = 1 ft = 0.3 m).CL: Centreline • HOL: Hogline • TL: Teeline • BL: Backline • HA: Hackline with Hacks • FGZ: Free Guard Zone

Curling stone

The curling stone (also sometimes called a rock in North America) is made of granite and is specified by the World Curling Federation, which requires a weight between 19.96 and 17.24 kilograms (44 and 38 lb), a maximum circumference of 914 millimetres (36 in), and a minimum height of 114 millimetres (4+1⁄2 in). The only part of the stone in contact with the ice is the running surface, a narrow, flat annulus or ring, 6.4 to 12.7 millimetres (1⁄4 to 1⁄2 in) wide and about 130 millimetres (5 in) in diameter; the sides of the stone bulge convex down to the ring, with the inside of the ring hollowed concave to clear the ice. This concave bottom was first proposed by J. S. Russell of Toronto, Ontario, Canada sometime after 1870, and was subsequently adopted by Scottish stone manufacturer Andrew Kay.

The curling stone or rock is made of granite

The curling stone or rock is made of granite An old-style curling stone

An old-style curling stone

The granite for the stones comes from two sources: Ailsa Craig, an island off the Ayrshire coast of Scotland, and the Trefor Granite Quarry, North of the Llŷn Peninsula, Gwynedd in Wales. These locations provide four variations in colour known as Ailsa Craig Common Green, Ailsa Craig Blue Hone, Blue Trefor and Red Trefor.

Blue Hone has very low water absorption, which prevents the action of repeatedly freezing water from eroding the stone. Ailsa Craig Common Green is a lesser quality granite than Blue Hone. In the past, most curling stones were made from Blue Hone, but the island is now a wildlife reserve, and the quarry is restricted by environmental conditions that exclude blasting.

Kays of Scotland has been making curling stones in Mauchline, Ayrshire, since 1851 and has the exclusive rights to the Ailsa Craig granite, granted by the Marquess of Ailsa, whose family has owned the island since 1560. According to the 1881 Census, Andrew Kay employed 30 people in his curling stone factory in Mauchline. The last harvest of Ailsa Craig granite by Kays took place in 2013, after a hiatus of 11 years; 2,000 tons were harvested, sufficient to fill anticipated orders through at least 2020. Kays have been involved in providing curling stones for the Winter Olympics since Chamonix in 1924 and has been the exclusive manufacturer of curling stones for the Olympics since the 2006 Winter Olympics.

Trefor granite comes from the Yr Eifl or Trefor Granite Quarry in the village of Trefor on the north coast of the Llŷn Peninsula in Gwynedd, Wales and has produced granite since 1850. Trefor granite comes in shades of pink, blue, and grey. The quarry supplies curling stone granite exclusively to the Canada Curling Stone Company, which has been producing stones since 1992 and supplied the stones for the 2002 Winter Olympics.

A handle is attached by a bolt running vertically through a hole in the centre of the stone. The handle allows the stone to be gripped and rotated upon release; on properly prepared ice the rotation will bend (curl) the path of the stone in the direction in which the front edge of the stone is turning, especially as the stone slows. Handles are coloured to identify each team, two popular colours in major tournaments being red and yellow. In competition, an electronic handle known as the Eye on the Hog may be fitted to detect hog line violations. This electronically detects whether the thrower's hand is in contact with the handle as it passes the hog line and indicates a violation by lights at the base of the handle (see delivery below). The eye on the hog eliminates human error and the need for hog line officials. It is mandatory in high-level national and international competition, but its cost, around US$650 each, currently puts it beyond the reach of most curling clubs.

Curling broom

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The curling broom, or brush, is used to sweep the ice surface in the path of the stone (see sweeping) and is also often used as a balancing aid during delivery of the stone.

Prior to the 1950s, most curling brooms were made of corn strands and were similar to household brooms of the day. In 1958, Fern Marchessault of Montreal inverted the corn straw in the centre of the broom. This style of corn broom was referred to as the Blackjack.

Artificial brooms made from human-made fabrics rather than corn, such as the Rink Rat, also became common later during this time period. Prior to the late sixties, Scottish curling brushes were used primarily by some of the Scots, as well as by recreational and elderly curlers, as a substitute for corn brooms, since the technique was easier to learn. In the late sixties, competitive curlers from Calgary, Alberta, such as John Mayer, Bruce Stewart, and, later, the world junior championship teams skipped by Paul Gowsell, proved that the curling brush could be just as (or more) effective without all the blisters common to corn broom use. During that time period, there was much debate in competitive curling circles as to which sweeping device was more effective: brush or broom. Eventually, the brush won out with the majority of curlers making the switch to the less costly and more efficient brush. Today, brushes have replaced traditional corn brooms at every level of curling; it is rare now to see a curler using a corn broom on a regular basis.

Curling brushes may have fabric, hog hair, or horsehair heads. Modern curling brush handles are usually hollow tubes made of fibreglass or carbon fibre instead of a solid length of wooden dowel. These hollow tube handles are lighter and stronger than wooden handles, allowing faster sweeping and more downward force to be applied to the broom head with reduced shaft flex.

In 2014, new "directional fabric" brooms were introduced, which could influence the path of a curling stone better than the existing brooms. Concerns arose that these brooms would alter the fundamentals of the sport by reducing the level of skill required and giving players an unfair advantage; at least thirty-four elite teams signed a statement pledging not to use them. This was dubbed the broomgate controversy. The new brooms were temporarily banned by the World Curling Federation and Curling Canada for the 2015–2016 season. Since 2016, only one standardized brush head is approved by the World Curling Federation for competitive play.

Shoes

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Curling shoes are similar to ordinary athletic shoes except for special soles; the slider shoe (usually known as a "slider") is designed for the sliding foot and the "gripper shoe" (usually known as a gripper) for the foot that kicks off from the hack.

The slider is designed to slide and typically has a Teflon sole. It is worn by the thrower during delivery from the hack and by sweepers or the skip to glide down the ice when sweeping or otherwise traveling down the sheet quickly. Stainless steel and "red brick" sliders with lateral blocks of PVC on the sole are also available as alternatives to Teflon. Most shoes have a full-sole sliding surface, but some shoes have a sliding surface covering only the outline of the shoe and other enhancements with the full-sole slider. Some shoes have small disc sliders covering the front and heel portions or only the front portion of the foot, which allow more flexibility in the sliding foot for curlers playing with tuck deliveries. When a player is not throwing, the player's slider shoe can be temporarily rendered non-slippery by using a slip-on gripper. Ordinary athletic shoes may be converted to sliders by using a step-on or slip-on Teflon slider or by applying electrical or gaffer tape directly to the sole or over a piece of cardboard. This arrangement often suits casual or beginning players.

The gripper is worn by the thrower on the foot that kicks off from the hack during delivery and is designed to grip the ice. It may have a normal athletic shoe sole or a special layer of rubbery material applied to the sole of a thickness to match the sliding shoe. The toe of the hack foot shoe may also have a rubberised coating on the top surface or a flap that hangs over the toe to reduce wear on the top of the shoe as it drags on the ice behind the thrower.

Other equipment

Other types of equipment include:

- Curling pants, made to be stretchy to accommodate the curling delivery.

- A stopwatch to time the stones over a fixed distance to calculate their speed. Stopwatches can be attached either to clothing or the broom.

- Curling gloves and mittens, to keep the hands warm and improve grip on the broom.

Gameplay

The purpose of a game is to score points by getting stones closer to the house centre, or the "button", than the other team's stones. Players from either team alternate in taking shots from the far side of the sheet. An end is complete when all eight rocks from each team have been delivered, a total of sixteen stones. If the teams are tied at the end of regulation, often extra ends are played to break the tie. The winner is the team with the highest score after all ends have been completed (see Scoring below). A game may be conceded if winning the game is infeasible.

International competitive games are generally ten ends, so most of the national championships that send a representative to the World Championships or Olympics also play ten ends. However, there is a movement on the World Curling Tour to make the games only eight ends. Most tournaments on that tour are eight ends, as are the vast majority of recreational games.

In international competition, each side is given 73 minutes to complete all of its throws. Each team is also allowed two minute-long timeouts per 10-end game. If extra ends are required, each team is allowed 10 minutes of playing time to complete its throws and one added 60-second timeout for each extra end. However, the "thinking time" system, in which the delivering team's game timer stops as soon as the shooter's rock crosses the t-line during the delivery, is becoming more popular, especially in Canada. This system allows each team 38 minutes per 10 ends, or 30 minutes per 8 ends, to make strategic and tactical decisions, with 4 minutes and 30 seconds an end for extra ends. The "thinking time" system was implemented after it was recognized that using shots which take more time for the stones to come to rest was being penalized in terms of the time the teams had available compared to teams which primarily use hits which require far less time per shot.

Delivery

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The process of sliding a stone down the sheet is known as the delivery or throw. Players, with the exception of the skip, take turns throwing and sweeping; when one player (e.g., the lead) throws, the players not delivering (the second and third) sweep (see Sweeping, below). When the skip throws, the vice-skip takes their role.

The skip, or the captain of the team, determines the desired stone placement and the required weight, turn, and line that will allow the stone to stop there. The placement will be influenced by the tactics at this point in the game, which may involve taking out, blocking, or tapping another stone.

- The weight of the stone is its velocity, which depends on the leg drive of the delivery rather than the arm.

- The turn or curl is the rotation of the stone, which gives it a curved trajectory.

- The line is the direction of the throw ignoring the effect of the turn.

The skip may communicate the weight, turn, line, and other tactics by calling or tapping a broom on the ice. In the case of a takeout, guard, or a tap, the skip will indicate the stones involved.

Before delivery, the running surface of the stone is wiped clean and the path across the ice swept with the broom if necessary, since any dirt on the bottom of a stone or in its path can alter the trajectory and ruin the shot. Intrusion by a foreign object is called a pick-up or pick.

The thrower starts from the hack. The thrower's gripper shoe (with the non-slippery sole) is positioned against one of the hacks; for a right-handed curler the right foot is placed against the left hack and vice versa for a left-hander. The thrower, now in the hack, lines the body up with shoulders square to the skip's broom at the far end for line.

The stone is placed in front of the foot now in the hack. Rising slightly from the hack, the thrower pulls the stone back (some older curlers may actually raise the stone in this backward movement) then lunges smoothly out from the hack pushing the stone ahead while the slider foot is moved in front of the gripper foot, which trails behind. The thrust from this lunge determines the weight, and hence the distance the stone will travel. Balance may be assisted by a broom held in the free hand with the back of the broom down so that it slides. One older writer suggests the player keep "a basilisk glance" at the mark.

There are two common types of delivery currently, the typical flat-foot delivery and the Manitoba tuck delivery where the curler slides on the front ball of their foot.

When the player releases the stone, a rotation (called the turn) is imparted by a slight clockwise or counter-clockwise twist of the handle from around the two or ten o'clock position to the twelve o'clock on release. A typical rate of turn is about 2+1⁄2 rotations before coming to a rest.

The stone must be released before its front edge crosses the near hog line. In major tournaments, the "Eye on the Hog" sensor is commonly used to enforce this rule. The sensor is in the handle of the stone and will indicate whether the stone was released before the near hog line. The lights on the stone handle will either light up green, indicating that the stone has been legally thrown, or red, in which case the illegally thrown stone will be immediately pulled from play instead of waiting for the stone to come to rest.

The stone must clear the far hog line or else be removed from play (hogged); an exception is made if a stone fails to come to rest beyond the far hog line after rebounding from a stone in play just past the hog line.

Sweeping

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

After the stone is delivered, its trajectory is influenced by the two sweepers under instruction from the skip. Sweeping is done for several reasons: to make the stone travel further, to decrease the amount of curl, and to clean debris from the stone's path. Sweeping is able to make the stone travel further and straighter by slightly melting the ice under the brooms, thus decreasing the friction as the stone travels across that part of the ice. The stones curl more as they slow down, so sweeping early in travel tends to increase distance as well as straighten the path, and sweeping after sideways motion is established can increase the sideways distance.

One of the basic technical aspects of curling is knowing when to sweep. When the ice in front of the stone is swept, a stone will usually travel both further and straighter, and in some situations one of those is not desirable. For example, a stone may be traveling too fast (said to have too much weight), but require sweeping to prevent curling into another stone. The team must decide which is better: getting by the other stone, but traveling too far, or hitting the stone.

Much of the yelling that goes on during a curling game is the skip and sweepers exchanging information about the stone's line and weight and deciding whether to sweep. The skip evaluates the path of the stone and calls to the sweepers to sweep as necessary to maintain the intended track. The sweepers themselves are responsible for judging the weight of the stone, ensuring that the length of travel is correct and communicating the weight of the stone back to the skip. Many teams use a number system to communicate in which of 10 zones the sweepers estimate the stone will stop. Some sweepers use stopwatches to time the stone from the back line or tee line to the nearest hog line to aid in estimating how far the stone will travel.

Usually, the two sweepers will be on opposite sides of the stone's path, although depending on which side the sweepers' strengths lie this may not always be the case. Speed and pressure are vital to sweeping. In gripping the broom, one hand should be one third of the way from the top (non-brush end) of the handle while the other hand should be one third of the way from the head of the broom. The angle of the broom to the ice should be such that the most force possible can be exerted on the ice. The precise amount of pressure may vary from relatively light brushing ("just cleaning" - to ensure debris will not alter the stone's path) to maximum-pressure scrubbing.

Sweeping is allowed anywhere on the ice up to the tee line; once the leading edge of a stone crosses the tee line only one player may sweep it. Additionally, if a stone is behind the tee line one player from the opposing team is allowed to sweep it. This is the only case that a stone may be swept by an opposing team member. In international rules, this player must be the skip, but if the skip is throwing, then the sweeping player must be the third.

Burning a stone

Occasionally, players may accidentally touch a stone with their broom or a body part. This is often referred to as burning a stone. Players touching a stone in such a manner are expected to call their own infraction as a matter of good sportsmanship. Touching a stationary stone when no stones are in motion (there is no delivery in progress) is not an infraction as long as the stone is struck in such a manner that its position is not altered, and this is a common way for the skip to indicate a stone that is to be taken out.

When a stone is touched when stones are in play, the remedies vary between leaving the stones as they end up after the touch, replacing the stones as they would have been if no stone were touched, or removal of the touched stone from play. In non-officiated league play, the skip of the non-offending team has the final say on where the stones are placed after the infraction.

Types of shots

Many different types of shots are used to carefully place stones for strategic or tactical reasons; they fall into three fundamental categories as follows:

Guards are thrown in front of the house in the free guard zone, usually to protect a stone or to make the opposing team's shot difficult. Guard shots include the centre-guard, on the centreline, and the corner-guards to the left or right sides of the centre line. See Free Guard Zone below.

Draws are thrown only to reach the house. Draw shots include raise, come-around, and freeze shots.

Takeouts are intended to remove stones from play and include the peel, hit-and-roll, and double shots.

For a more complete listing, see Glossary of curling terms.

Free guard zone

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The free guard zone is the area of the curling sheet between the hog line and tee line, excluding the house. Until five stones have been played (three from the side without hammer and two from the side with hammer), stones in the free guard zone may not be removed by an opponent's stone, although they can be moved within the playing area. If a stone in the free guard zone is knocked out of play, it is placed back in the position it was in before the shot was thrown and the opponent's stone is removed from play. This rule is known as the five-rock rule or the free guard zone rule (previous versions of the free guard zone rule only limited removing guards from play in the first three or four rocks).

This rule, a relatively recent addition to curling, was added in response to a strategy by teams of gaining a lead in the game and then peeling all of the opponents' stones (knocking them out of play at an angle that caused the shooter's stone to also roll out of play, leaving no stones on the ice). By knocking all stones out the opponents could at best score one point, if they had the last stone of the end (called the hammer). If the team peeling the rocks had the hammer they could peel rock after rock which would blank the end (leave the end scoreless), keeping the last rock advantage for another end. This strategy had developed (mostly in Canada) as ice-makers had become skilled at creating a predictable ice surface and newer brushes allowed greater control over the rock. While a sound strategy, this made for an unexciting game. Observers at the time noted that if two teams equally skilled in the peel game faced each other on good ice, the outcome of the game would be predictable from who won the coin flip to have last rock (or had earned it in the schedule) at the beginning of the game. The 1990 Brier (Canadian men's championship) was considered by many curling fans as boring to watch because of the amount of peeling and the quick adoption of the free guard zone rule the following year reflected how disliked this aspect of the game had become.

The free guard zone rule was originally called the Modified Moncton Rule and was developed from a suggestion made by Russ Howard for the Moncton 100 cashspiel in Moncton, New Brunswick, in January 1990. "Howard's Rule" (later known as the Moncton Rule), used for the tournament and based on a practice drill his team used, had the first four rocks in play unable to be removed no matter where they were at any time during the end. This method of play was altered by restricting the area in which a stone was protected to the free guard zone only for the first four rocks thrown and adopted as a four-rock free guard zone rule for international competition shortly after. Canada kept to the traditional rules until a three-rock free guard zone rule was adopted for the 1993–94 season. After several years of having the three-rock rule used for the Canadian championships and the winners then having to adjust to the four-rock rule in the World Championships, the Canadian Curling Association adopted the four-rock free guard zone in the 2002–03 season.

One strategy that has been developed by curlers in response to the free guard zone (Kevin Martin from Alberta is one of the best examples) is the "tick" game, where a shot is made attempting to knock (tick) the guard to the side, far enough that it is difficult or impossible to use, but still remaining in play while the shot itself goes out of play. The effect is functionally identical to peeling the guard, but significantly harder, as a shot that hits the guard too hard (knocking it out of play) results in it being replaced, while not hitting it hard enough can result in it still being tactically useful for the opposition. There is also a greater chance that the shot will miss the guard entirely because of the greater accuracy required to make the shot. Because of the difficulty of making this type of shot, only the best teams will normally attempt it, and it does not dominate the game the way the peel formerly did. Steve Gould from Manitoba popularized ticks played across the face of the guard stone. These are easier to make because they impart less speed on the object stone, therefore increasing the chance that it remains in play even if a bigger chunk of it is hit.

With the tick shot reducing the effectiveness of the four-rock rule, the Grand Slam of Curling series of bonspiels adopted a five-rock rule in 2014. In 2017, the five-rock rule was adopted by the World Curling Federation and member organizations for official play, beginning in the 2018–19 season.

Hammer

The last rock in an end is called the hammer, and throwing the hammer gives a team a tactical advantage. Before the game, teams typically decide who gets the hammer in the first end either by chance (such as a coin toss), by a "draw-to-the-button" contest, where a representative of each team shoots to see who gets closer to the centre of the rings, or, particularly in tournament settings like the Winter Olympics, by a comparison of each team's win–loss record. In all subsequent ends, the team that did not score in the preceding end gets to throw second, thus having the hammer. In the event that neither team scores, called a blanked end, the hammer remains with the same team. Naturally, it is easier to score points with the hammer than without; the team with the hammer generally tries to score two or more points. If only one point is possible, the skip may try to avoid scoring at all in order to retain the hammer the next end, giving the team another chance to use the hammer advantage to try to score two points. Scoring without the hammer is commonly referred to as stealing, or a steal, and is much more difficult.

Strategy

Curling is a game of strategy, tactics, and skill. The strategy depends on the team's skill, the opponent's skill, the conditions of the ice, the score of the game, how many ends remain and whether the team has last-stone advantage (the hammer). A team may play an end aggressively or defensively. Aggressive playing will put a lot of stones in play by throwing mostly draws; this makes for an exciting game and although risky the rewards can be great. Defensive playing will throw a lot of hits preventing a lot of stones in play; this tends to be less exciting and less risky. A good drawing team will usually opt to play aggressively, while a good hitting team will opt to play defensively.

If a team does not have the hammer in an end, it will opt to try to clog up the four-foot zone in the house to deny the opposing team access to the button. This can be done by throwing "centre line" guards in front of the house on the centre line, which can be tapped into the house later or drawn around. If a team has the hammer, they will try to keep this four-foot zone free so that they have access to the button area at all times. A team with the hammer may throw a corner guard as their first stone of an end placed in front of the house, but outside the four-foot zone to utilize the free guard zone. Corner guards are key for a team to score two points in an end, because they can either draw around it later or hit and roll behind it, making the opposing team's shot to remove it more difficult.

Ideally, the strategy in an end for a team with the hammer is to score two points or more. Scoring one point is often a wasted opportunity, as they will then lose last-stone advantage for the next end. If a team cannot score two points, they will often attempt to "blank an end" by removing any leftover opposition stones and rolling out; or, if there are no opposition stones, just throwing the stone through the house so that no team scores any points, and the team with the hammer can try again the next end to score two or more with it. Generally, a team without the hammer would want to either force the team with the hammer to only one point, so that they can get the hammer back, or "steal" the end by scoring one or more points of their own.

Large leads are often defended by displacing the opponent's stones to reduce their opportunity to score multiple points. However, a comfortably leading team that leaves their own stones in play becomes vulnerable as the opponent can draw around guard stones, stones in the house can be "tapped back" if they are in front of the tee line, or "frozen onto" if they are behind the tee line. A frozen stone is placed in front of and touching the opponent's stone and is difficult to remove. At this point, a team may opt for "peels"; throws with a lot of "weight" that can move opposition stones out of play.

Conceding a game

It is common at any level for a losing team to terminate the match before all ends are completed if it believes it no longer has a realistic chance of winning. Competitive games end once the losing team has "run out of rocks"—that is, once it has fewer stones in play and available for play than the number of points needed to tie the game.

Dispute resolution

Most decisions about rules are left to the skips, although in official tournaments, decisions may be left to the officials. However, all scoring disputes are handled by the vice skip. No players other than the vice skip from each team should be in the house while score is being determined. In tournament play, the most frequent circumstance in which a decision has to be made by someone other than the vice skip is the failure of the vice skips to agree on which stone is closest to the button. An independent official (supervisor at Canadian and World championships) then measures the distances using a specially designed device that pivots at the centre of the button. When no independent officials are available, the vice skips measure the distances.

Scoring

The winner is the team having the highest number of accumulated points at the completion of ten ends. Points are scored at the conclusion of each of these ends as follows: when each team has thrown its eight stones, the team with the stone closest to the button wins that end; the winning team is then awarded one point for each of its own stones lying closer to the button than the opponent's closest stone.

Only stones that are in the house are considered in the scoring. A stone is in the house if it lies within the 12-foot (3.7 m) zone or any portion of its edge lies over the edge of the ring. Since the bottom of the stone is rounded, a stone just barely in the house will not have any actual contact with the ring, which will pass under the rounded edge of the stone, but it still counts. This type of stone is known as a biter.

It may not be obvious to the eye which of the two rocks is closer to the button (centre) or if a rock is actually biting or not. There are specialized devices to make these determinations, but these cannot be brought out until after an end is completed. Therefore, a team may make strategic decisions during an end based on assumptions of rock position that turn out to be incorrect.

The score is marked on a scoreboard, of which there are two types; the baseball type and the club scoreboard.

The baseball-style scoreboard was created for televised games for audiences not familiar with the club scoreboard. The ends are marked by columns 1 through to the regulation number of ends for the competition (usually with an extra column to account for the possibility of an extra end to break ties) plus an additional column for the total. Below this are two rows, one for each team, containing the team's score for that end and their total score in the right-hand column.

The club scoreboard is traditional and used in most curling clubs. Scoring on this board only requires the use of (up to) 11 digit cards, whereas with baseball-type scoring an unknown number of multiples of the digits (especially low digits like 1 and especially 0) may be needed. The numbered centre row represents various possible scores, and the numbers placed in the team rows represent the end in which that team achieved that cumulative score. If the red team scores three points in the first end (called a three-ender), then a 1 (indicating the first end) is placed beside the number 3 in the red row. If they score two more in the second end, then a 2 will be placed beside the 5 in the red row, indicating that the red team has five points in total (3 + 2). This scoreboard works because only one team can get points in an end. However, some confusion may arise if neither team scores points in an end, this is called a blank end. The blank end numbers are usually listed in the furthest column on the right in the row of the team that has the hammer (last rock advantage), or on a special spot for blank ends.

The following example illustrates the difference between the two types. The example illustrates the men's final at the 2006 Winter Olympics.

| Team | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Final |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | X | X | 10 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | X | X | 4 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | |||||||||||||

| Points | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | Blank ends |

| 1 | 5 | 8 | 7 |

Eight points – all the rocks thrown by one team counting – is the highest score possible in an end, and is known as an "eight-ender" or "snowman". Scoring an eight-ender is very difficult; in curling, it is the equivalent of pitching a perfect game in baseball. Probably the best-known snowman came at the 2006 Players' Championships. Future (2007) World Champion Kelly Scott scored eight points in one of her games against 1998 World bronze medalist Cathy King.

Culture

Competition teams are normally named after the skip, for example, Team Martin after skip Kevin Martin. Amateur league players can (and do) creatively name their teams, but when in competition (a bonspiel) the official team will have a standard name.

Top curling championships are typically played by all-male or all-female teams. It is known as mixed curling when a team consists of two men and two women. For many years, in the absence of world championship or Olympic mixed curling events, national championships (of which the Canadian Mixed Curling Championship was the most prominent) were the highest-level mixed curling competitions. However, a European Mixed Curling Championship was inaugurated in 2005, a World Mixed Doubles Curling Championship was established in 2008, and the European Mixed Championship was replaced with the World Mixed Curling Championship in 2015. A mixed tournament was held at the Olympic level for the first time in 2018, although it was a doubles tournament, not a four-person.

Curling tournaments may use the Schenkel system for determining the participants in matches.

Curling is played in many countries, including Canada, the United Kingdom (especially Scotland), the United States, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, and Japan, all of which compete in the world championships.

Curling has been depicted by many artists including: George Harvey, John Levack, The Dutch School, Charles Martin Hardie, John Elliot Maguire, John McGhie, and John George Brown.

Curling is particularly popular in Canada. Improvements in ice making and changes in the rules to increase scoring and promote complex strategy have increased the already high popularity of the sport in Canada, and large television audiences watch annual curling telecasts, especially the Scotties Tournament of Hearts (the national championship for women), the Montana's Brier (the national championship for men), and the women's and men's world championships.

Despite the Canadian province of Manitoba's small population (ranked 5th of 10 Canadian provinces), Manitoban teams have won the Brier more times than teams from any other province, except for Alberta. The Tournament of Hearts and the Brier are contested by provincial and territorial champions, and the world championships by national champions.

Curling is the provincial sport of Saskatchewan. From there, Ernie Richardson and his family team dominated Canadian and international curling during the late 1950s and early 1960s and have been considered to be the best male curlers of all time. Sandra Schmirler led her team to the first-ever gold medal in women's curling in the 1998 Winter Olympics. When she died two years later from cancer, over 15,000 people attended her funeral, and it was broadcast on national television.

Good sportsmanship

More so than in many other team sports, good sportsmanship, often referred to as the "Spirit of Curling", is an integral part of curling. The Spirit of Curling also leads teams to congratulate their opponents for making a good shot, strong sweeping, or spectacular form. Perhaps most importantly, the Spirit of Curling dictates that one never cheers mistakes, misses, or gaffes by one's opponent (unlike most team sports), and one should not celebrate one's own good shots during the game beyond modest acknowledgement of the shot such as a head nod, fist bump, or thumbs-up gesture. Modest congratulation, however, may be exchanged between winning team members after the match. On-the-ice celebration is usually reserved for the winners of a major tournament after winning the final game of the championship. It is completely unacceptable to attempt to throw opposing players off their game by way of negative comment, distraction, or heckling.

A match traditionally begins with players shaking hands with and saying "good curling" or "have a pleasant game" to each member of the opposing team. It is also traditional in some areas for the winning team to buy the losing team a drink after the game. Even at the highest levels of play, players are expected to call their own fouls.

It is not uncommon for a team to concede a curling match after it believes it no longer has any hope of winning. Concession is an honourable act and does not carry the stigma associated with quitting. It also allows for more socializing. To concede a match, members of the losing team offer congratulatory handshakes to the winning team. Thanks, wishes of future good luck, and hugs are usually exchanged between the teams. To continue playing when a team has no realistic chance of winning can be seen as a breach of etiquette.

Accessibility

Main article: Wheelchair curling

Curling has been adapted for wheelchair users and people otherwise unable to throw the stone from the hack. These curlers may use a device known as a "delivery stick". The cue holds on to the handle of the stone and is then pushed along by the curler. At the end of delivery, the curler pulls back on the cue, which releases it from the stone. The Canadian Curling Association Rules of Curling allows the use of a delivery stick in club play, but does not permit it in championships.

The delivery stick was specifically invented for elderly curlers in Canada in 1999. In early 2016 an international initiative started to allow use of the delivery sticks by players over 60 years of age in World Curling Federation Senior Championships, as well as in any projected Masters (60+) Championship that develops in the future.

Terminology

For an extensive glossary of terminology, see Glossary of curling.Terms used to describe the game include:

The ice in the game may be fast (keen) or slow. If the ice is keen, a rock will travel further with a given amount of weight (throwing force) on it. The speed of the ice is measured in seconds. One such measure, known as "hog-to-hog" time, is the speed of the stone and is the time in seconds the rock takes from the moment it crosses the near hog line until it crosses the far hog line. If this number is lower, the rock is moving faster, so again low numbers mean more speed. The ice in a match will be somewhat consistent and thus this measure of speed can also be used to measure how far down the ice the rock will travel. Once it is determined that a rock taking (for example) 13 seconds to go from hog line to hog line will stop on the tee line, the curler can know that if the hog-to-hog time is matched by a future stone, that stone will likely stop at approximately the same location. As an example, on keen ice, common times might be 16 seconds for guards, 14 seconds for draws, and 8 seconds for peel weight.

The back line to hog line speed is used principally by sweepers to get an initial sense of the weight of a stone. As an example, on keen ice, common times might be 4.0 seconds for guards, 3.8 seconds for draws, 3.2 for normal hit weight, and 2.9 seconds for peel weight. Especially at the club level, this metric can be misleading, due to amateurs sometimes pushing stones on release, causing the stone to travel faster than the back-to-hog speed.

Champions and major championships

- Curling at the Winter Olympics

- World Curling Championships

- World Junior Curling Championships

- World Senior Curling Championships

- World Mixed Doubles Curling Championship

- European Curling Championships

- Continental Cup of Curling

- Montana's Brier

- Scotties Tournament of Hearts

- United States Men's Curling Championship

- United States Women's Curling Championship

- Canada Cup of Curling

- European Mixed Curling Championship

Notable clubs

Main article: Lists of curling clubs Notable curling clubs- Bemidji Curling Club – Bemidji, Minnesota, Home of the 2006 United States Men's & Women's Olympic Curling Teams

- Broomstones Curling Club – Wayland, Massachusetts

- Chicago Curling Club – Chicago, Illinois

- Dakota Curling Club – Burnsville, Minnesota – a leading example of the development of new curling clubs on arena ice in the USA

- Detroit Curling Club – Ferndale, Michigan

- Duluth Curling Club – Duluth, Minnesota – Home of the 2018 United States Men's Gold Medal Olympic Curling Team

- Garrison Golf and Curling Club, Kingston, Ontario

- Grand National Curling Club – Organization in the United States covering clubs on the east coast

- Granite Curling Club – Winnipeg, Manitoba

- Granite Curling Club – Seattle, Washington, the only dedicated curling facility on the west coast of the United States

- Ice Melters Curling Club – England

- Markinch Curling Club – Fife, Scotland

- Mayflower Curling Club – Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Milwaukee Curling Club – Mequon, Wisconsin — The oldest curling club in the U.S. – Since 1845

- Ottawa Curling Club – Ottawa, Ontario

- Potomac Curling Club – Laurel, Maryland – Near Washington, D.C.

- Pittsburgh Curling Club – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania – Established in 2002

- Plainfield Curling Club – South Plainfield, New Jersey

- Rideau Curling Club – Ottawa, Ontario

- Royal Caledonian Curling Club – Scotland, the official Mother Club of curling

- Royal Montreal Curling Club – Montreal, Quebec, the oldest active athletic club in North America

- Royal City Curling Club – New Westminster, British Columbia

- Saint Paul Curling Club – St. Paul, Minnesota – Founded in 1885. Club with largest active membership in the United States (over 1000 members).

- Utica Curling Club – Utica, New York

- Kilsyth Curling Club – the first constituted curling club in the world

In popular culture

- The Beatles participate in a game of curling during one scene of their 1965 film Help!. The villains booby-trap one of the curling stones with a bomb; George sees the "fiendish thingy" and tells everyone to run. The bomb eventually goes off after a delay, creating a big hole in the ice.

- The 1969 James Bond film On Her Majesty's Secret Service features scenes of curling.

- Men with Brooms is a 2002 Canadian film that takes a satirical look at curling. A TV adaptation, also titled Men with Brooms, debuted in 2010 on CBC Television.

- The Corner Gas episode "Hurry Hard" involves the townspeople of Dog River competing in a local curling bonspiel for the fictitious "Clavet Cup". The episode also features cameos by Canadian curlers Randy Ferbey and Dave Nedohin.

- In Louise Penny's mystery novel A Fatal Grace, published in 2007, the main character investigates a murder at a local Christmas bonspiel.

- "Boy Meets Curl" is a 2010 episode from The Simpsons: Homer and Marge form a mixed curling team with Agnes and Seymour Skinner, which is chosen to play in the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, where they win the gold medal.

- The Move of the Penguin is a 2013 Italian comedy film where an unlikely team tries to qualify for the 2006 Winter Olympics held in Turin.

- In 2021, the sitcom The Great North aired the episode "Curl Interrupted Adventure" in which two characters join a curling league.

See also

- Glossary of curling

- Grand Slam of Curling

- List of curlers

- World Curling Federation

- University and college curling

- Women's curling

- Drummuir Curlers' Platform railway station

References

- "Curling Makes Gains in U.S. Popularity". Yahoo! Sports. 19 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014.

- Wetzel, Dan (19 February 2010). "Don't take curling for granite". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "Curling Canada | The basics of playing the game". Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- "Wooden Curling Stone". Wisconsin Historical Society. 23 February 2006. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "The world's oldest curling stone". The Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "History of the Game". Scottish Curling. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Eberlin, Amy. "The Flemish and the game of 'curling'". Scotland and the Flemish People. University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Kerr, John (1890). The History of Curling: And Fifty Years of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club. Edinburgh: David Douglas. p. 79. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Adamson, Henry. "The muses threnodie, or, mirthfull mournings, on the death of Master Gall Containing varietie of pleasant poëticall descriptions, morall instructions, historiall narrations, and divine observations, with the most remarkable antiquities of Scotland, especially at Perth By Mr. H. Adamson". Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "Curling". Olympic Games. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "SND". Dsl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- Kerr, John (1890). History of curling, Scotland's ain game, and fifty years of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club. Edinburgh: David Douglas. p. 115. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "Kilsyth Curling History". Paperclip.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "Curling: History". Olympic Sport History. International Olympic Committee. 4 February 2018. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- Curling: An illustrated History, by David B Smith ISBN 0 85976 074 X

- Ramsay, John (1882). An Account of the Game of Curling, with Songs for the Canon-Mills Curling Club. Edinburgh. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Wooden Curling Stone". Wisconsin Historical Society. 23 April 2013. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Kerr, John (1890). History of curling, Scotland's ain game, and fifty years of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club. Edinburgh: David Douglas. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Cairnie, J. (1833). Essay on curling, and artificial pond making. Glasgow: W. R. McPhun. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Watson, Thomas (1894). Kirkintilloch, town and parish. Glasgow: J. Smith. p. 312. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Bell, Henry Glassford (1874). The Poetical Works of David Gray. J. Maclehose. pp. 16–17. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Schorstein, Jon (director). "The Grand Match". Moving Image Archive. National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- Baker, Nate (ed.). The Book of Old Darvel and Some of its Famous Sons. Darvel: Walker & Connell. pp. 12–13.

- ^ Doug Maxwell. Canada Curls - An Illustrated History of Curling in Canada. Whitecap Books.

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: Details Every Public and Private Passenger Station, Halt, Platform and Stopping Place, Past and Present (1st ed.). Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- "The Club". The Royal Montreal Curling Club. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "World Rankings". World Curling Federation. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Mixed Doubles curling confirmed for PyeongChang 2018 Olympics". World Curling Federation. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Lattimer, George M., ed. (1932). "III Winter Olympic Games, Lake Placid 1932, Official Report" (PDF). pp. 255–258. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- "Canadians Win At Curling: Beat United States, 12 Games to 3, in Exhibition Series and after all olympic matches they have a giant ice orgy with all the countries!". The New York Times. 6 February 1932. Sports, p. 20. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ "The Rules of Curling and Rules of Competition". World Curling Federation. October 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- Branch, John (17 August 2009). "Curlers Are Finicky When It Comes to Their Olympic Ice". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017.

- "USA-Today: Curlers Play Nice and Leave No Stone Unturned" (Press release). Twin Cities Curling Association. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012.

- Hendry, Erica R. "Why Curling Ice is Different Than Other Ice". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Smooth operators: They make Olympic ice nice". Today in Vancouver. MSNBC. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- Paulley, Glenn (7 March 2020). "Curling stones: taken for granite – Throwing Stones". Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- "About Curling/Stones". Anchorage Curling Club. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "1881 Census entry for Haugh, Mauchline, Ayrshire GRO Ref Volume 604 EnumDist 1 Page 3". Scotland's People. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "News". Kays of Scotland. Archived from the original on 26 February 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "Mauchline, 9 Barskimming Road, Kay's Curling Stone Factory". Canmore. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "Welsh Stone Forum newsletter" (PDF). October 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "The History of Curling". Canadian Curling Association. 18 January 2013. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- "Top curling teams say they won't use high-tech brooms". CBC News. 16 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- Ouellette, Jennifer (12 June 2016). "Here's the Physics Behind the 'Broomgate' Controversy Rocking the Sport of Curling". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- "Curling Canada bans broom heads with 'directional fabric'". CTV News. 27 November 2015. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Brush Head Moratorium". Canadian Curling Association. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- "Curling Shoes:Choosing a Slider". Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- "Curling Explained to non Curlers by Cameron Scott". Sporting Life 360. 14 February 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- "Eight is Great! Asham World Curling Tour Events, Including Grand Slams, move to Eight-End Format". World Curling Tour. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "Rules of Curling for General Play". Canadian Curling Association. October 2014. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- DeSaulniers, Darren (26 March 2010). "Ferraro's hack innovation remains curling standard". Ottawa Citizen. p. B5. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017 – via PressReader.

- Bannerman, Gordon (11 November 2013). "Curling: Stormont Loch hosts outdoor bonspiel". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Syers, Edgar and Madge (1908). The book of winter sports. London: Edward Arnold. p. 29. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Kerr, John (1890). History of curling, Scotland's ain game, and fifty years of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club. Edinburgh: David Douglas. p. 402. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Wiecek, Paul (7 March 2016). "Team of 'tuckers'". Winnipeg Free Press. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016.

- "Why Curlers Sweep the Ice". Business Insider. 14 February 2014. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "The Sports Science of Curling: A Practical Review". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 41: 3. 2009. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000352606.48792.77. ISSN 0195-9131.

- "Rules of Curling". World Curling Federation. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "What is the five-rock rule?". Grand Slam of Curling. 19 September 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- McCormick, Murray (3 February 2018). "Curling's new five-rock free guard zone rule designed to generate offence". National Post. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Thiessen, Nolan (15 June 2018). "Thiessen Blog: Five-rock FGZ a Positive Change for Curling". Curling Canada. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Section 7 Basic Strategy". The Curling Manual. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Peebles, Frank (16 January 2023). "Rocks align for Waffle rink to score eight-ender at Quesnel Curling Club". Quesnel Cariboo Observer. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- "North Shore curling team scores eight-ender". North Shore News. 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- "What are the odds? Windsor rink scores 8-ender". CBC. 22 December 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- "Eight-ender scored in curling match in Langley". CBC. 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- Jala, David (20 November 2019). "Rare curling eight-ender recorded at Sydney club". SaltWire. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- "Shooting Percentages". CurlingZone. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- "Curling 8 Ender". YouTube. Archived from the original on 22 September 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- Harvey, George. "The Curlers". ArtUK. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Harvey, George. "The Curlers". ArtUK. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Levack, John. "The Curlers at Rawyards". ArtUK. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Dutch School". ArtUK. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Hardie, Charles Martin. "Curling at Carsebreck". ArtUK. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Maguire, John Elliot. "Curling Stone Workshop". ArtUK. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- McGhie, John. "The Curlers". ArtUK. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Curling;—a Scottish Game, at Central Park". The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "Kings of the World: The Curling Richardsons". CBC Television. 13 March 2004. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007.

- "Spirit of Curling". RCMP Curling Club, Ottawa. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Pearson, Patricia (March–April 2009). "How one woman fell in love with curling". Best Health. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- "Section 4 - Using a Throwing Device". The Curling School. Curltech. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- World Masters Curling World Masters Curling| Archived 10 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Men With Brooms IMDB Entry". IMDb. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Glennon, Morgan (5 January 2012). "Men With Brooms: Requiem for an Obscure Canadian Sitcom". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- Stasio, Marilyn (10 June 2007). "Bodies of Evidence". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- "Curling in The Great North". Sports Illustrated. 28 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

Further reading

- Mott, Morris; Allardyce, John (1989). Curling Capital Winnipeg and the Roarin' Game, 1876 to 1988. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 0-88755-145-9.

- Murata, Jiro (2022). "Study of curling mechanism by precision kinematic measurements of curling stone's motion". Scientific Reports. 12 (1). 15047. arXiv:2203.00347. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1215047M. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-19303-4. PMC 9440934. PMID 36057647.

- Richard, Pierre (2006). Une Histoire Sociale du Curling au Québec, de 1807 à 1980 (in French). Trois-Rivières: Université du Québec.

- Smith, David B. (1981), Curling: An Illustrated History, John Donald Publishers Ltd., Edinburgh, ISBN 9780859760744

External links

- World Curling Federation

- CBC Digital Archives – Curling: Sweeping the Nation

- Bonspiel! The History of Curling in Canada at Library and Archives Canada

- curling stones, Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

- The Game Of The Magic Broom, March 1944 one of the first magazine articles to introduce the game of curling to the American public

- The Canadian Curler's Manual transcription of 1840 text

- Sportlistings.com - World Curling Federation Directory listing

| Team sports | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ball sports |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tag sports | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water sports | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other non-ball sports | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Ice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The solid state of water | |||||

| Major phases | |||||

| Formations | |||||

| Phenomena | |||||

| Ice-related activities |

| ||||

| Constructions | |||||

| Work | |||||

| Other uses | |||||

| Ice ages | |||||

| Celts and modern Celts | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celtic nations · Celtic studies · Celtic tribes · Celtic languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|  | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||