| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Furuta pendulum" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Furuta pendulum, or rotational inverted pendulum, consists of a driven arm which rotates in the horizontal plane and a pendulum attached to that arm which is free to rotate in the vertical plane. It was invented in 1992 at Tokyo Institute of Technology by Katsuhisa Furuta and his colleagues. It is an example of a complex nonlinear oscillator of interest in control system theory. The pendulum is underactuated and extremely non-linear due to the gravitational forces and the coupling arising from the Coriolis and centripetal forces. Since then, dozens, possibly hundreds of papers and theses have used the system to demonstrate linear and non-linear control laws. The system has also been the subject of two texts.

Equations of motion

Despite the great deal of attention the system has received, very few publications successfully derive (or use) the full dynamics. Many authors have only considered the rotational inertia of the pendulum for a single principal axis (or neglected it altogether). In other words, the inertia tensor only has a single non-zero element (or none), and the remaining two diagonal terms are zero. It is possible to find a pendulum system where the moment of inertia in one of the three principal axes is approximately zero, but not two.

A few authors have considered slender symmetric pendulums where the moments of inertia for two of the principal axes are equal and the remaining moment of inertia is zero. Of the dozens of publications surveyed for this wiki only a single conference paper and journal paper were found to include all three principal inertial terms of the pendulum. Both papers used a Lagrangian formulation but each contained minor errors (presumably typographical).

The equations of motion presented here are an extract from a paper on the Furuta pendulum dynamics derived at the University of Adelaide.

Definitions

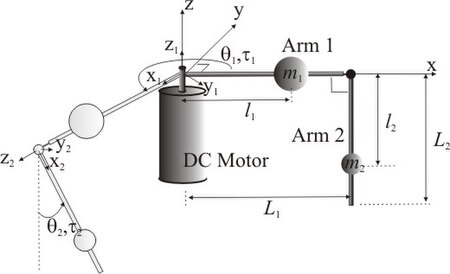

Consider the rotational inverted pendulum mounted to a DC motor as shown in Fig. 1. The DC motor is used to apply a torque to Arm 1. The link between Arm 1 and Arm 2 is not actuated but free to rotate. The two arms have lengths and . The arms have masses and which are located at and respectively, which are the lengths from the point of rotation of the arm to its center of mass. The arms have inertia tensors and (about the centre of mass of the arms respectively). Each rotational joint is viscously damped with damping coefficients and , where is the damping provided by the motor bearings and is the damping arising from the pin coupling between Arm 1 and Arm 2.

A right hand coordinate system has been used to define the inputs, states and the Cartesian coordinate systems 1 and 2. The coordinate axes of Arm 1 and Arm 2 are the principal axes such that the inertia tensors are diagonal.

The angular rotation of Arm 1, , is measured in the horizontal plane where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from above) is positive. The angular rotation of Arm 2, , is measured in the vertical plane where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from the front) is positive. When the Arm is hanging down in the stable equilibrium position .

The torque the servo-motor applies to Arm 1, , is positive in a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from above). A disturbance torque, , is experienced by Arm 2, where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from the front) is positive.

Assumptions

Before deriving the dynamics of the system a number of assumptions must be made. These are:

- The motor shaft and Arm 1 are assumed to be rigidly coupled and infinitely stiff.

- Arm 2 is assumed to be infinitely stiff.

- The coordinate axes of Arm1 and Arm 2 are the principal axes such that the inertia tensors are diagonal.

- The motor rotor inertia is assumed to be negligible. However, this term may be easily added to the moment of inertia of Arm 1.

- Only viscous damping is considered. All other forms of damping (such as Coulomb) have been neglected, however it is a simple exercise to add this to the final governing DE.

Non-linear Equations of Motion

The non-linear equations of motion are given by

and

Simplifications

Most Furuta pendulums tend to have long slender arms, such that the moment of inertia along the axis of the arms is negligible. In addition, most arms have rotational symmetry such that the moments of inertia in two of the principal axes are equal. Thus, the inertia tensors may be approximated as follows:

Further simplifications are obtained by making the following substitutions. The total moment of inertia of Arm 1 about the pivot point (using the parallel axis theorem) is . The total moment of inertia of Arm 2 about its pivot point is . Finally, define the total moment of inertia the motor rotor experiences when the pendulum (Arm 2) is in its equilibrium position (hanging vertically down), .

Substituting the previous definitions into the governing DEs gives the more compact form

and

See also

References

- Furuta, K., Yamakita, M. and Kobayashi, S. (1992) “Swing-up control of inverted pendulum using pseudo-state feedback”, Journal of Systems and Control Engineering, 206(6), 263-269.

- ^ Xu, Y., Iwase, M. and Furuta, K. (2001) “Time optimal swing-up control of single pendulum”, Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control, 123(3), 518-527.

- ^ Furuta, K., Iwase, M. (2004) “Swing-up time analysis of pendulum”, Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Technical Sciences, 52(3), 153-163.

- ^ Iwase, M., Åström, K.J., Furuta, K. and Åkesson, J. (2006) “Analysis of safe manual control by using Furuta pendulum”, Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Control Applications, 568-572.

- J.Á. Acosta, “Furuta's Pendulum: A Conservative Nonlinear Model for Theory and Practise,” Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2010, Article ID 742894, 29 pages. http://www.hindawi.com/journals/mpe/2010/742894.html

- ^ Åkesson, J. and Åström, K.J. (2001) “Safe Manual Control of the Furuta Pendulum”, In Proceedings 2001 IEEE International Conference on Control Applications (CCA'01), pp. 890-895.

- Olfati-Saber, R. (2001) “Nonlinear Control of Underactuated Mechanical Systems with Application to Robotics and Aerospace Vehicles”, PhD Thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA. http://www.cds.caltech.edu/~olfati/thesis/ Archived 2007-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fantoni, I. and Lozano, R. (2002) “Non-linear control of underactuated mechanical systems”, Springer-Verlag, London.

- ^ Egeland, O. and Gravdahl, T. (2002) “Modeling and Simulation for Automatic Control”, Marine Cybernetics, Trondheim, Norway, 639 pp., ISBN 82-92356-00-2.

- Hirata, H., Haga, K., Anabuki, M., Ouchi, S. and Ratiroch-Anant, P. (2006) “Self-Tuning Control for Rotation Type Inverted Pendulum Using Two Kinds of Adaptive Controllers”, Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Conference on Robotics, Automation and Mechatronics, 1-6. http://lab8.ec.u-tokai.ac.jp/RAM062.pdf Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Ratiroch-Anant, P., Anabuki, M. and Hirata, H. (2004) “Self-tuning control for rotational inverted pendulum by eigenvalue approach”, Proceedings of TENCON 2004, IEEE Region 10 Conference, Volume D, 542-545. http://lab8.ec.u-tokai.ac.jp/TENCON2004_D-542.pdf Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Baba, Y., Izutsu, M., Pan, Y. And Furuta, K. (2006) “Design of control method to rotate pendulum”, Proceedings of SICE-ICASE International Joint Conference, Korea.

- Craig, K. and Awtar, S. (2005) “Inverted pendulum systems: rotary and arm-driven a mechatronic system design case study”, Proceedings of the 7th Mechatronics Forum International Conference, Atlanta. http://www-personal.umich.edu/~awtar/craig_awtar_1.pdf Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Awtar, S., King, N., Allen, T., Bang, I., Hagan, M., Skidmore, D. and Craig, K. (2002) “Inverted pendulum systems: Rotary and arm-driven – A mechatronic system design case study”, Mechatronics, 12, 357-370. http://www-personal.umich.edu/~awtar/invertedpendulum_mechatronics.pdf Archived 2008-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cazzolato, B.S and Prime, Z (2011) "On the Dynamics of the Furuta Pendulum", Journal of Control Science and Engineering, Volume 2011 (2011), Article ID 528341, 8 pages. http://downloads.hindawi.com/journals/jcse/2011/528341.pdf

Further reading

- On the Dynamics of the Furuta Pendulum

- Furuta's Pendulum: A Conservative Nonlinear Model for Theory and Practise

- Dynamic Analysis of the Tilted Furuta Pendulum

External links

- The University of Adelaide Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine

- University of Toronto

- Ohio State University Archived 2008-09-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Example Rotary Inverted Pendulum

to Arm 1. The link between Arm 1 and Arm 2 is not actuated but free to rotate. The two arms have lengths

to Arm 1. The link between Arm 1 and Arm 2 is not actuated but free to rotate. The two arms have lengths  and

and  . The arms have masses

. The arms have masses  and

and  which are located at

which are located at  and

and  respectively, which are the lengths from the point of rotation of the arm to its center of mass. The arms have inertia tensors

respectively, which are the lengths from the point of rotation of the arm to its center of mass. The arms have inertia tensors  and

and  (about the centre of mass of the arms respectively). Each rotational joint is viscously damped with damping coefficients

(about the centre of mass of the arms respectively). Each rotational joint is viscously damped with damping coefficients  and

and  , where

, where  , is measured in the horizontal plane where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from above) is positive. The angular rotation of Arm 2,

, is measured in the horizontal plane where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from above) is positive. The angular rotation of Arm 2,  , is measured in the vertical plane where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from the front) is positive. When the Arm is hanging down in the stable equilibrium position

, is measured in the vertical plane where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from the front) is positive. When the Arm is hanging down in the stable equilibrium position  .

.

, is experienced by Arm 2, where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from the front) is positive.

, is experienced by Arm 2, where a counter-clockwise direction (when viewed from the front) is positive.

. The total moment of inertia of Arm 2 about its pivot

point is

. The total moment of inertia of Arm 2 about its pivot

point is  . Finally, define the total moment of inertia the motor

rotor experiences when the pendulum (Arm 2) is in its equilibrium position

(hanging vertically down),

. Finally, define the total moment of inertia the motor

rotor experiences when the pendulum (Arm 2) is in its equilibrium position

(hanging vertically down),  .

.