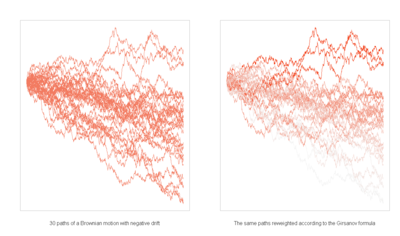

In probability theory, Girsanov's theorem or the Cameron-Martin-Girsanov theorem explains how stochastic processes change under changes in measure. The theorem is especially important in the theory of financial mathematics as it explains how to convert from the physical measure, which describes the probability that an underlying instrument (such as a share price or interest rate) will take a particular value or values, to the risk-neutral measure which is a very useful tool for evaluating the value of derivatives on the underlying.

History

Results of this type were first proved by Cameron-Martin in the 1940s and by Igor Girsanov in 1960. They have been subsequently extended to more general classes of process culminating in the general form of Lenglart (1977).

Significance

Girsanov's theorem is important in the general theory of stochastic processes since it enables the key result that if Q is a measure that is absolutely continuous with respect to P then every P-semimartingale is a Q-semimartingale.

Statement of theorem

We state the theorem first for the special case when the underlying stochastic process is a Wiener process. This special case is sufficient for risk-neutral pricing in the Black–Scholes model.

Let be a Wiener process on the Wiener probability space . Let be a measurable process adapted to the natural filtration of the Wiener process ; we assume that the usual conditions have been satisfied.

Given an adapted process define

where is the stochastic exponential of X with respect to W, i.e.

and denotes the quadratic variation of the process X.

If is a martingale then a probability measure Q can be defined on such that Radon–Nikodym derivative

Then for each t the measure Q restricted to the unaugmented sigma fields is equivalent to P restricted to

Furthermore, if is a local martingale under P then the process

is a Q local martingale on the filtered probability space .

Corollary

If X is a continuous process and W is Brownian motion under measure P then

is Brownian motion under Q.

The fact that is continuous is trivial; by Girsanov's theorem it is a Q local martingale, and by computing

it follows by Levy's characterization of Brownian motion that this is a Q Brownian motion.

Comments

In many common applications, the process X is defined by

For X of this form then a necessary and sufficient condition for to be a martingale is Novikov's condition which requires that

The stochastic exponential is the process Z which solves the stochastic differential equation

The measure Q constructed above is not equivalent to P on as this would only be the case if the Radon–Nikodym derivative were a uniformly integrable martingale, which the exponential martingale described above is not. On the other hand, as long as Novikov's condition is satisfied the measures are equivalent on .

Additionally, then combining this above observation in this case, we see that the process

for is a Q Brownian motion. This was Igor Girsanov's original formulation of the above theorem.

Application to finance

This theorem can be used to show in the Black–Scholes model the unique risk-neutral measure, i.e. the measure in which the fair value of a derivative is the discounted expected value, Q, is specified by

Application to Langevin equations

Another application of this theorem, also given in the original paper of Igor Girsanov, is for stochastic differential equations. Specifically, let us consider the equation

where denotes a Brownian motion. Here and are fixed deterministic functions. We assume that this equation has a unique strong solution on . In this case Girsanov's theorem may be used to compute functionals of directly in terms a related functional for Brownian motion. More specifically, we have for any bounded functional on continuous functions that

This follows by applying Girsanov's theorem, and the above observation, to the martingale process

In particular, with the notation above, the process

is a Q Brownian motion. Rewriting this in differential form as

we see that the law of under Q solves the equation defining , as is a Q Brownian motion. In particular, we see that the right-hand side may be written as , where Q is the measure taken with respect to the process Y, so the result now is just the statement of Girsanov's theorem.

A more general form of this application is that if both

admit unique strong solutions on , then for any bounded functional on , we have that

See also

- Cameron–Martin theorem – Theorem defining translation of Gaussian measures (Wiener measures) on Hilbert spaces.

References

- Liptser, Robert S.; Shiriaev, A. N. (2001). Statistics of Random Processes (2nd, rev. and exp. ed.). Springer. ISBN 3-540-63929-2.

- Dellacherie, C.; Meyer, P.-A. (1982). "Decomposition of Supermartingales, Applications". Probabilities and Potential. Vol. B. Translated by Wilson, J. P. North-Holland. pp. 183–308. ISBN 0-444-86526-8.

- Lenglart, E. (1977). "Transformation de martingales locales par changement absolue continu de probabilités". Zeitschrift für Wahrscheinlichkeit (in French). 39: 65–70. doi:10.1007/BF01844873.

External links

- Notes on Stochastic Calculus which contain a simple outline proof of Girsanov's theorem.

be a Wiener process on the Wiener probability space

be a Wiener process on the Wiener probability space  . Let

. Let  be a measurable process adapted to the natural filtration of the Wiener process

be a measurable process adapted to the natural filtration of the Wiener process  ; we assume that the usual conditions have been satisfied.

; we assume that the usual conditions have been satisfied.

is the

is the

denotes the

denotes the  is a

is a  such that

such that

is equivalent to P restricted to

is equivalent to P restricted to

is a local martingale under P then the process

is a local martingale under P then the process

.

.

is continuous is trivial; by Girsanov's theorem it is a Q local martingale, and by computing

is continuous is trivial; by Girsanov's theorem it is a Q local martingale, and by computing

as this would only be the case if the Radon–Nikodym derivative were a uniformly integrable martingale, which the exponential martingale described above is not. On the other hand, as long as Novikov's condition is satisfied the measures are equivalent on

as this would only be the case if the Radon–Nikodym derivative were a uniformly integrable martingale, which the exponential martingale described above is not. On the other hand, as long as Novikov's condition is satisfied the measures are equivalent on  .

.

is a Q Brownian motion. This was Igor Girsanov's original formulation of the above theorem.

is a Q Brownian motion. This was Igor Girsanov's original formulation of the above theorem.

denotes a Brownian motion. Here

denotes a Brownian motion. Here  and

and  are fixed deterministic functions. We assume that this equation has a unique strong solution on

are fixed deterministic functions. We assume that this equation has a unique strong solution on  . In this case Girsanov's theorem may be used to compute functionals of

. In this case Girsanov's theorem may be used to compute functionals of  on continuous functions

on continuous functions  that

that

, where Q is the measure taken with respect to the process Y, so the result now is just the statement of Girsanov's theorem.

, where Q is the measure taken with respect to the process Y, so the result now is just the statement of Girsanov's theorem.