| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Pronunciation of English ⟨wh⟩" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| History and description of |

| English pronunciation |

|---|

| Historical stages |

| General development |

| Development of vowels |

| Development of consonants |

| Variable features |

| Related topics |

The pronunciation of the digraph ⟨wh⟩ in English has changed over time, and still varies today between different regions and accents. It is now most commonly pronounced /w/, the same as a plain initial ⟨w⟩, although some dialects, particularly those of Scotland, Ireland, and the Southern United States, retain the traditional pronunciation /hw/, generally realized as [ʍ], a voiceless "w" sound. The process by which the historical /hw/ has become /w/ in most modern varieties of English is called the wine–whine merger. It is also referred to as glide cluster reduction.

Before rounded vowels, a different reduction process took place in Middle English, as a result of which the ⟨wh⟩ in words like who and whom is now pronounced /h/. (A similar sound change occurred earlier in the word how.)

Early history

What is now English ⟨wh⟩ originated as the Proto-Indo-European consonant *kʷ (whose reflexes came to be written ⟨qu⟩ in Latin and the Romance languages). In the Germanic languages, in accordance with Grimm's Law, Indo-European voiceless stops became voiceless fricatives in most environments. Thus the labialized velar stop *kʷ initially became presumably a labialized velar fricative *xʷ in pre-Proto-Germanic, then probably becoming * – a voiceless labio-velar approximant – in Proto-Germanic proper. The sound was used in Gothic and represented by the letter hwair. In Old High German, it was written as ⟨huu⟩, a spelling also used in Old English along with ⟨hƿ⟩ (using the letter wynn). In Middle English the spelling was changed to ⟨hw⟩ (with the development of the letter ⟨w⟩) and then ⟨wh⟩, but the pronunciation remained .

Because Proto-Indo-European interrogative words typically began with *kʷ, English interrogative words (such as who, which, what, when, where) typically begin with ⟨wh⟩ (for the word how, see below). As a result, such words are often called wh-words, and questions formed from them are called wh-questions. In reference to this English order, a common cross-lingual grammatical phenomenon affecting interrogative words is called wh-movement.

Developments before rounded vowels

Before rounded vowels, such as /uː/ or /oː/, there was a tendency, beginning in the Old English period, for the sound /h/ to become labialized, causing it to sound like /hw/. Words with an established /hw/ in that position came to be perceived (and spelt) as beginning with plain /h/. This occurred with the interrogative word how (Proto-Germanic *hwō, Old English hū).

A similar process of labialization of /h/ before rounded vowels occurred in the Middle English period, around the 15th century, in some dialects. Some words which historically began with /h/ came to be written ⟨wh⟩ (whole, whore). Later in many dialects /hw/ was delabialized to /h/ in the same environment, regardless of whether the historic pronunciation was /h/ or /hw/ (in some other dialects the labialized /h/ was reduced instead to /w/, leading to such pronunciations as the traditional Kentish /woʊm/ for home). This process affected the pronoun who and its inflected forms. These had escaped the earlier reduction to /h/ because they had unrounded vowels in Old English, but by Middle English the vowel had become rounded, and so the /hw/ of these words was now subject to delabialization:

- who – Old English hwā, Modern English /huː/

- whom – Old English hwǣm, Modern English /huːm/

- whose – Old English hwās, Modern English /huːz/

By contrast with how, these words changed after their spelling with ⟨wh⟩ had become established, and thus continue to be written with ⟨wh⟩ like the other interrogative words which, what, etc. (which were not affected by the above changes since they had unrounded vowels – the vowel of what became rounded at a later time).

Wine–whine merger

of wine, whine

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The wine–whine merger is the phonological merger by which /hw/, historically realized as a voiceless labio-velar approximant , comes to be pronounced the same as plain /w/, that is, as a voiced labio-velar approximant . John C. Wells refers to this process as Glide Cluster Reduction. It causes the distinction to be lost between the pronunciation of ⟨wh⟩ and that of ⟨w⟩, so pairs of words like wine/whine, wet/whet, weather/whether, wail/whale, Wales/whales, wear/where, witch/which become homophones. This merger has taken place in the dialects of the great majority of English speakers.

Extent of the merger

The merger seems to have been present in the south of England as early as the 13th century. It was unacceptable in educated speech until the late 18th century, but there is no longer generally any stigma attached to either pronunciation. In the late nineteenth century, Alexander John Ellis found that /hw/ was retained in all wh- words throughout Cumbria, Northumberland, Scotland and the Isle of Man, but the distinction was largely absent throughout the rest of England.

The merger is essentially complete in England, Wales, the West Indies, South Africa, Australia, and in the speech of young speakers in New Zealand. However, some conservative RP speakers in England may use /hw/ for ⟨wh⟩, a conscious choice rather than a natural feature of their accent.

The merger is not found in Scotland, most of Ireland (although the distinction is usually lost in Belfast and some other urban areas of Northern Ireland), and in the speech of older speakers in New Zealand. The distribution of the wh- sound in words does not always exactly match the standard spelling; for example, Scots pronounce whelk with plain /w/, while in many regions weasel has the wh- sound.

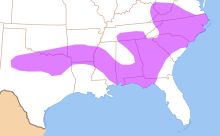

Most speakers in the United States and Canada have the merger. According to Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006: 49), using data collected in the 1990s, there are regions of the U.S. (particularly in the Southeast) in which speakers keeping the distinction are about as numerous as those having the merger, but there are no regions in which the preservation of the distinction is predominant (see map). Throughout the U.S. and Canada, about 83% of respondents in the survey had the merger completely, while about 17% preserved at least some trace of the distinction.

Possible homophones

Below is a list of word pairs that are likely to be pronounced as homophones by speakers having the wine–whine merger.

| /w/ | /hw/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| wack | whack | ˈwæk | |

| wail | whale | ˈweɪl | With pane–pain merger |

| wale | whale | ˈweɪl, ˈweːl | |

| Wales | whales | ˈweɪlz, ˈweːlz | |

| wang | whang | ˈwæŋ | |

| ware | where | ˈwɛː(r), ˈweːr | |

| wary | wherry | ˈwɛri | With Mary-marry-merry merger |

| watt | what | ˈwɒt | In certain dialects |

| way | whey | ˈweɪ | |

| weal | wheel | ˈwiːl | |

| wear | where | ˈwɛː(r), ˈweːr | |

| weather | whether | ˈwɛðə(r) | |

| weigh | whey | ˈweɪ | With wait–weight merger |

| we'll | wheel | ˈwiːl | In certain dialects |

| welp | whelp | ˈwɛlp | |

| wen | when | ˈwɛn | |

| were (man) | where | ˈwɛː(r), ˈweːr | |

| were (to be) | whir | ˈwɜː(r) | |

| wet | whet | ˈwɛt | |

| wether | whether | ˈwɛðə(r) | |

| wide | why'd | ˈwaɪd | |

| wield | wheeled | ˈwiːld | |

| wig | whig | ˈwɪɡ | |

| wight | white | ˈwaɪt | |

| wile | while | ˈwaɪl | In certain dialects |

| win | when | ˈwɪn | With pin-pen merger |

| win | whin | ˈwɪn | |

| wince | whence | ˈwɪns | With pin-pen merger |

| wind (verb) | whined | ˈwaɪnd | |

| wine | whine | ˈwaɪn | |

| wined | whined | ˈwaɪnd | |

| wire | why're | ˈwaɪə(r) | |

| wise | why's | ˈwaɪz | |

| wish | whish | ˈwɪʃ | |

| wit | whit | ˈwɪt | |

| witch | which | ˈwɪtʃ | |

| wither | whither | ˈwɪðə(r) | |

| woe | whoa | ˈwoʊ, ˈwoː | |

| word | whirred | ˈwɜː(r)d | With nurse merger |

| world | whirled | ˈwɜː(r)ld | With nurse merger |

| world | whorled | ˈwɜː(r)ld | In certain dialects |

| Y; wye | why | ˈwaɪ |

Pronunciations and phonological analysis of the distinct wh sound

As mentioned above, the sound of initial ⟨wh⟩, when distinguished from plain ⟨w⟩, is often pronounced as a voiceless labio-velar approximant , a voiceless version of the ordinary sound. In some accents, however, the pronunciation is more like , and in some Scottish dialects it may be closer to or —the sound preceded by a voiceless velar fricative or stop. (In other places the /kw/ of qu- words is reduced to .) In the Black Isle, the /hw/ (like /h/ generally) is traditionally not pronounced at all. Pronunciations of the or type are reflected in the former Scots spelling quh- (as in quhen for when, etc.).

In some dialects of Scots, the sequence /hw/ has merged with the voiceless labiodental fricative /f/. Thus whit ("what") is pronounced /fɪt/, whan ("when") becomes /fan/, and whine becomes /fain/ (a homophone of fine). This is also found in some Irish English with an Irish Gaelic substrate influence (which has led to a re-borrowing of whisk(e)y as Irish Gaelic fuisce, the word having originally entered English from Scottish Gaelic).

Phonologically, the distinct sound of ⟨wh⟩ is often analyzed as the consonant cluster /hw/, and it is transcribed so in most dictionaries. When it has the pronunciation , however, it may also be analyzed as a single phoneme, /ʍ/.

In popular culture

- A portrayal of the regional retention of the distinct wh- sound is found in the speech of the character Frank Underwood, a South Carolina politician, in the American television series House of Cards.

- The show King of the Hill, set in Texas, pokes fun at the issue through character Hank Hill's prominent, exaggerated pronunciation.

- A similar gag is in several episodes of Family Guy, with Brian becoming annoyed by Stewie's heavy emphasis of the /hw/ sound in his pronunciation of "Cool hWhip" and "hWil hWheaton"; a commercial closely approximating the Cool Whip dialog was put out for "hWheat Thins".

- In the comedy movie Hot Rod, the titular character Rod declares that his "safe word will be hwhiskey" and an exchange of overemphasized /hw/ ensues.

- American linguist Dr. Jackson Crawford has stated that he uses , which he picked up from his grandmother's accent.

See also

References

- Based on www.ling.upenn.edu and the map at Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006: 50).

- ^ Labov, William; Sharon Ash; Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- ^ Wells, J.C., Accents of English, CUP 1982, pp. 228–229.

- Minkova, Donka (2004). "Philology, linguistics, and the history of /hw/~/w/". In Anne Curzan; Kimberly Emmons (eds.). Studies in the History of the English language II: Unfolding Conversations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 7–46. ISBN 3-11-018097-9.

- Maguire, Warren. "Retention of /hw/ in wh- words". An Atlas of Alexander J. Ellis's The Existing Phonology of English Dialects. University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 2022-05-08.

- ^ Wells, 1982, p. 408.

- Robert McColl Millar, Northern and Insular Scots, Edinburgh University Press (2007), p. 62.

- Barber, C.L., Early Modern English, Edinburgh University Press 1997, p. 18.

- A similar phenomenon to this has occurred in most varieties of the Māori language.

- Family Guy: Brian and Stewie, Cool Whip

- Family Guy: Stewie, Wil Wheaton

- See for example the YouTube video Fox Broadcasting Company (April 13, 2012), Family Guy - Wheat Thins, archived from the original on 2021-12-13, retrieved November 3, 2020

| History of English | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||