Thomas Blount (1618–1679) was an English antiquarian and lexicographer.

Background

He was the son of Myles Blount of Orleton in Herefordshire and was born at Bordesley, Tardebigge, Worcestershire. He was called to the bar at the Inner Temple, but, being a zealous Roman Catholic, his religion interfered considerably with the practice of that profession at a time when Catholics were excluded from almost all areas of public life in England. Retiring to his estate at Orleton, he devoted himself to the study of the law as an amateur, and also read widely in other branches of knowledge.

Thomas Blount married Anne Church of Maldon, Essex (1617–1697) in 1661 and they had one daughter, Elizabeth (1662–1724). He died on 26 December 1679, at Orleton, Herefordshire, at the age of sixty-one.

Glossographia

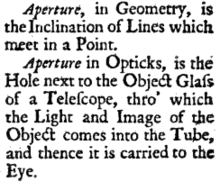

His principal works include Glossographia; or, a dictionary interpreting the hard words of whatsoever language, now used in our refined English tongue (1656), which went through several editions and remains amusing and instructive reading. It defined around 11,000 hard or unusual words, and was the largest English dictionary when it was published. His was the last, largest, and greatest of the English "hard-word" dictionaries, which aimed not to present a complete listing of English words, but to define and explain unusual terms that might be encountered in literature or the professions, thus aiding the burgeoning non-academic middle class, which was ascendant in England at the time and of which Blount was a member. Glossographia marked several "firsts" in English lexicography. It was the first dictionary that included illustrations (two woodcuts of heraldic devices) and etymologies, and the first that cited sources for definitions. It contained many unusual words that had not previously been included in dictionaries, and others not included in any later dictionary. While some of these were neologisms, Blount did not coin any words himself, but rather reported on the rather inventive culture of classically inspired coinages of the period.

Unfortunately for Blount, his Glossographia was surpassed in popularity with the publication in 1658 of The New World of Words by Edward Phillips (1630–1696), whose uncle was John Milton. While Phillips' dictionary was much larger than Blount's (ca. 20,000 words) and included some common words in addition to unusual ones, it is now widely acknowledged that Phillips copied many definitions from Blount. This act of plagiarism enraged Blount, who began to denounce his rival vitriolically in print. Blount and Phillips engaged for many years in a publishing war, undertaking constant revisions of their works accompanied by denunciations of the other. In 1673, Blount published A World of Errors Discovered in the New World of Words, wherein he sought to demonstrate that where Phillips was correct, he was not often original, and that where he was original, he was not often correct. He wrote, indignantly, "Must this then be suffered? A Gentleman for his divertissement writes a Book, and this Book happens to be acceptable to the World, and sell; a Bookseller, not interested in the Copy, instantly employs some Mercenary to jumble up another like Book out of this, with some Alterations and Additions, and give it a new Title; and the first Author's out-done, and his Publisher half undone...." Phillips retorted by publishing a list of words from Blount that he contended were "barbarous and illegally compounded." The dispute was not settled prior to Blount's death, thus granting a default victory to Phillips. Regardless, Glossographia went through many editions and even more reprintings, the latest of which was in 1969.

Other works

In addition to his dictionary, Blount published widely on other subjects. His Boscobel (1651) was an account of Charles II's preservation after Worcester, with the addition of the king's own account dictated to Pepys; the book was edited with a bibliography by C. G. Thomas (1894). Blount remained an amateur scholar of law throughout his life, and published Nomolexicon: a law dictionary interpreting such difficult and obscure words and terms as are found either in our common or statute, ancient or modern lawes (1670; third edition, with additions by W. Nelson, 1717), to aid the profession that he was unable to practice. He was also an antiquarian of some note, and his Fragmenta Antiquitatis: Ancient Tenures of land, and jocular customs of some manners (1679; enlarged by J. Beckwith and republished, with additions by H. M. Beckwith, in 1815; again revised and enlarged by W. C. Hazlitt, 1874) is a sort of encyclopaedia of folk-customs and manorial traditions.

The following bibliography is reproduced from the foreword of Beckwith's edition of Fragmenta where it is part of a short biography reproduced from Anthony á Wood's Athenae Oxonienses.

- The Academy of Eloquence, containing a complete English Rhetoric Printed at London in the time of the rebellion; and several times after.

- Glossographia; or, a Dictionary interpreting such hard Words, whether Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Italian, &c, that are now used in our refined English Tongue, &c. London, 1656, octavo, published several times after with additions and amendments

- The Lamps of the Law, and Lights of the Gospel; or, the Titles of some late Spiritual, Polemical, and Metaphysical new Books, London, 1653, in 8vo. written in imitation of J. Birkenhead's Paul's Church-yard, and published under the name of Grass and Hay Withers.

- Boscobel; or, the History of his Majesty's Escape after the Battle of Worcester, 3d September, 1651. London, 1660, in 8vo.; there again 1680, in 8vo. third edition, translated into French and Portuguese; the last of which was done by Peter Gifford, of White Ladies, in Staffordshire, a Roman Catholic. Vide No. 11.

- The Catholic Almanack, for 1661, 62, 63, &c. which selling not so well' as Joh. Booker's Almanack did, he therefore wrote,

- Booker rebuked; or, Animadversions on Booker's Teiescopium Uranicum or Ephemeris, 1665, which is very erroneous, &c. London, 1665, quarto, in one sheet, which made much sport among people, having had the assistance therein of Jo. Sargeant and Jo. Austen.

- A Law Dictionary, interpreting such difficult and obscure Words and Terms as are found either in our Common or Statute, antient or modern Laws. London, 1671, fol. There again in 1691, with some Corrections, and the addition of above 600 Words. (This is the Νομολεζιχν.)

- Animadversions upon Sir Richard Baker's Chronicle and its Continuation, &c. Oxon, 1672, 8vo.

- A World of Errors discovered in the New World of Words, &c. London, 1673, fol, written against Edw. Philips his book, entitled, A New World of English Words.

- Fragmenta Antiquitatis, antient Tenures of Land, and Jocular Customs of some Manors, &c. London, 1679, 8vo.

- Boscobel, &c, the second part, London, 1681, 8vo, to which is added, Claustrum regale reseratum; or, the King's Concealment at Trent, in Somersetshire, published by Mrs. Anne Windham, of Trent. (See No. 4.)

References

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Blount, Thomas" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- The copyright-protected The Phrontistery, the latter with the permission of the author

- "Blount, Thomas (1618-1679)" . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Works by Thomas Blount at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Blount at the Internet Archive